Historical Background

Naval Operations

In addition to money and supplies, which more than once saved the American cause from disaster, the most conspicuous French contribution to American independence was at sea. Adm. Francois de Grasse, sealing off the mouth of Chesapeake Bay with his French Fleet in the fall of 1781, made possible the decisive American victory at Yorktown which marked the end of major operations. (See p. 73.)

Although the Continental Congress established an American Navy and a Marine Corps in the fall of 1775, the initiative at sea remained in the hands of the powerful British Navy until Yorktown. Most of the memorable exploits of the U.S. Navy took the form of small, individual engagements. Strangely enough, the most significant American naval "victory" of the war was fought on an inland lake by a force of soldiers under command of a brigadier general, and resulted in the loss of the American fleet (Valcour Bay, pp. 135-136).

Among the notable exploits on salt water were the spectacular raid on the Irish Channel coast of England by Capt. Lambert Wickes' three small ships in May 1777 and John Paul Jones' celebrated cruise around Great Britain in the late summer of 1779. The climax to Jones' exploit was the successful engagement of his flagship, the Bonhomme Richard, with the English Serapis on September 23, when he is reported to have said the immortal words, "I have not yet begun to fight."

|

| This narrow bay between Valcour Island (in the distance) and the west shore of Lake Champlain was the scene of an 8-hour battle between Benedict Arnold's 15 hastily built vessels and a British fleet of 29 craft. Arnold lost his fleet, but won precious time for the American cause in the autumn of 1776. (Courtesy, New York State Education Department.) |

The land war went well in the first year. George Washington built up his army in the Boston siege lines during the winter of 1775-76, and by spring had sealed off the British defenders so effectively that their position clearly became untenable. On March 17, 1776, General Howe's army sailed away to Nova Scotia, leaving Boston and 250 cannon in the hands of the Revolutionary Army.

Meanwhile, an ambitious campaign had been launched against Canada. Gen. Richard Montgomery was to advance up Lake Champlain toward Montreal while Gen. Benedict Arnold marched up the Kennebec River in Maine and down the Chaudiere to Quebec. It was a desperate gamble, but Canada was lightly garrisoned and the Americans hoped that France would come to their aid. Although Montgomery's army suffered from hunger, fatigue, and sickness, it moved swiftly and captured Montreal in mid-November 1775. Arnold also reached his objective. His decimated army arrived at Quebec after an epic march through the Maine wilderness, but was too weak to take the city alone. (See p. 200.) Montgomery joined Arnold, and the combined forces attacked Quebec on December 31, 1775. The assault failed after Montgomery was slain and Arnold badly wounded. The American Army held on until the following spring; in June 1776 Arnold's successor, Gen. John Sullivan, fell back to Lake Champlain.

The English had not been idle. Early in 1776 Gen. Sir Henry Clinton led an expedition down the Atlantic coast to cooperate with the strong Tory factions in the Southern States. The command got off to a late start and, by the time Clinton reached an appointed rendezvous, Tory forces in Virginia and North Carolina had been defeated and dispersed. He then decided to capture Charleston, S.C., for use as a base of operations. A 4-week siege, beginning on June 1, was beaten off by the determined resistance of Col. William Moultrie's small force on Sullivan's Island.

After the evacuation of Boston, British and American eyes turned to New York, strategically situated between New England and the Middle and Southern States. Washington moved his army to the vicinity of New York City in April and May 1776, posting part on Long Island and the rest on Manhattan Island. General Howe's British Army arrived in August and disembarked on Long Island. Attacking on August 27, the British outflanked Washington's forward line and drove the defenders back to fortifications on Brooklyn Heights. There Howe commenced siege operations. But Washington, appreciating his danger, skillfully evacuated Long Island on the foggy night of August 29-30.

Howe landed on Manhattan on September 15, forcing Washington to evacuate New York City. The Americans won a small but encouraging victory at Harlem Heights during the withdrawal. (See pp. 130-131.) Howe's command of the numerous waterways gave him an enormous advantage over Washington. In mid-October the British crossed to the mainland in Washington's left rear and forced him back to White Plains. After a sharp and skillfully fought action there on October 28, he withdrew again.

The American situation now deteriorated rapidly. Washington had left part of his force to hold Forts Washington and Lee, on opposite sides of the Hudson at the upper end of Manhattan Island, and now he left part to hold the highlands of the Hudson while he led the remainder across the river into New Jersey. Moving quickly to attack the forts, Howe captured Fort Washington with its entire garrison on November 16, and 3 days later forced Gen. Nathanael Greene to evacuate Fort Lee. His army disintegrating, Washington began a rapid retreat across New Jersey. The British advance under Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis followed closely. Washington's difficulties were compounded by the inexplicable refusal of Gen. Charles Lee, despite repeated orders, to join him with a major portion of the American Army. In early December, Washington crossed the Delaware River into Pennsylvania with the remnants of his army. Howe left garrisons at Princeton, Trenton, Bordentown, New Brunswick, and Perth Amboy, and withdrew the rest of his force to winter quarters at New York City. Another British detachment was sent to capture Newport, R.I., where it remained in garrison.

|

| Morris-Jumel Mansion. General Washington made his headquarters from mid-September to mid-October 1776 in this handsome home built by Roger Morris in 1765. Morris was a loyalist and had left the country at the outbreak of war. The house was later the property of Stephen Jumel. (Courtesy, New York City Department of Parks.) |

While Washington had been suffering these setbacks, affairs on Lake Champlain had taken a turn for the better. Gen. Horatio Gates, who was ordered on June 17 to take command of the American forces that had retreated from Canada, withdrew the force from Crown Point to Fort Ticonderoga. Learning that Gen. Sir Guy Carleton, British commander in Canada, was assembling a fleet for a drive up Lake Champlain, Gates ordered Arnold to build an American fleet. Arnold fell to work with furious energy, and his small "navy," manned by landsmen, fearlessly engaged Carleton's advance at Valcour Bay on October 11, 1776. In 2 days of fighting he lost most of the vessels, but the delay convinced Carleton that he could do nothing decisive before the onset of winter. (See pp. 135-136.) Early in November the British retired to the north end of Lake Champlain.

|

| A Pennsylvania State Park preserves the site where Washington embarked his troops for the crossing of the Delaware on Christmas night, 1776. The brilliant raid on Trenton heartened the American cause at a critical period in the struggle for independence. (National Park Service) |

Meanwhile, Washington planned to inflict a stunning surprise on the British. He understood that, if he hoped to recruit his army for an other year of service, he must win a victory. On Christmas night of 1776, he crossed the Delaware River and struck the Hessian outpost at Trenton, N.J. The surprised garrison quickly surrendered, and Washington recrossed the river with prisoners and materiel. (See pp. 121-23.)

Although the terms of enlistment of his army expired with the old year, Washington persuaded most of the men to serve for 6 weeks longer. He again entered New Jersey on the night of December 30-31, 1776, with them and reinforcements of militia. A British force under Lord Cornwallis confronted Washington, and the American position seemed hopeless. But by a swift march Washington eluded Cornwallis and struck the British supply base at Princeton on January 3, 1777. (See pp. 119-121.) Driving the British out, he moved his army northeast to Morristown. The British evacuated New Jersey, and the front quieted down for several months.

|

| The Gilpin House, used by Lafayette as headquarters at the time of the Battle of Brandywine, has been restored and preserved in Brandywine Battlefield State Park, overlooking Chadd's Ford, Pa. (National Park Service) |

With the opening of active operations in the spring of 1777, the War for Independence reached a crisis in the North. Strong British forces poised at opposite ends of the Hudson River-Lake Champlain line, and a coordinated advance by both almost inevitably would have produced a British victory of major proportions. Fortunately for the Americans, divided British command resulted in the defeat of one of the armies while the other stood idly by.

Faced with the double mission of guarding the capital at Philadelphia and preventing a move by Howe up the Hudson River, Washington spent most of the spring and summer of 1777 marching and counter-marching through New Jersey. In mid-August Howe decided on an offensive against the American Capital. He loaded his army on transports at New York and sailed south. After a long and circuitous voyage, he disembarked at the head of Chesapeake Bay. Washington moved his army to Brandywine Creek, southwest of Philadelphia, and there engaged the British advance on September 11. The Americans were outflanked and forced to withdraw (see pp. 139-140), and the British entered Philadelphia on September 26.

Washington launched an attack on the main British outpost at Germantown on October 4. After a promising start, the American assault was blunted and the attackers driven from the field. Howe was now able to turn his attention to the American forts along the Delaware below Philadelphia, which were evacuated soon afterward. Washington put his army in winter quarters at Valley Forge, 20 miles north west of Philadelphia.

|

| A view of part of the encampment area at Valley Forge National Historical Park, used by the Continental Army in the winter and spring of 1777-78. (National Park Service) |

Meanwhile, expecting a simultaneous advance up the Hudson by Howe, Gen. John Burgoyne's British Army had started south from Canada in June 1777. Another British force, under Gen. Barry St. Leger, was to advance eastward along the Mohawk Valley from Fort Oswego. St. Leger reached Fort Stanwix early in August, laid siege to the post, and shortly afterward ambushed a militia relief force at Oriskany (See pp. 131-132.) Two weeks later, however, General Arnold arrived with another relief column and compelled St. Leger to lift the siege and retire.

Burgoyne reached Fort Ticonderoga on June 27 and speedily forced Gen. Arthur St. Clair's American garrison to evacuate. Pursuing the retreating Americans southward, however, the British left the easier water route and began a difficult march overland. Burgoyne's advance was opposed by a weak American force under Gen. Philip Schuyler, who hampered the British as best he could by felling trees and destroying bridges. Weak as he was, Schuyler was farsighted enough to send Arnold with the relief expedition that saved Fort Stanwix from St. Leger.

The savage conduct of Burgoyne's Indian allies aroused the New York and New England militia, a circumstance that led to the first major defeat suffered by the invading force. A Hessian foraging party, numbering about a tenth of Burgoyne's army, was nearly wiped out by militiamen from Bennington, Vt., on August 16, 1777. (See pp. 124-125.)

|

| Maj. Gen. John Stark, commander of a brigade of New Hampshire militia, was the victor at Bennington. He had served in the French and Indian Wars and at the Battle of Bunker Hill, and participated in the defeat of Burgoyne at Saratoga. (U.S. Army photo.) |

By September, Burgoyne had learned that Howe was not coming to join him, but he decided nevertheless not to withdraw to Canada. He crossed the Hudson at Saratoga on September 13 and attacked the Americans, now under General Gates, 6 days later. Unable to break through, Burgoyne remained inactive for 3 weeks, having received word that reinforcements under Clinton were advancing north from New York City. Clinton successfully captured two forts below West Point, but failed to follow up his success. Burgoyne, his position growing daily more desperate, made another unsuccessful attack on October 7. Surrounded at Saratoga, he surrendered his army to Gates 10 days later. This victory at Saratoga, which encouraged the French alliance and boosted patriot hopes tremendously, is generally regarded as the turning point of the War for Independence. (See pp. 62-63, 211).

Washington's army suffered bitter hardships at Valley Forge during the winter of 1777-78. (See pp. 153-154.) The country was far from destitute, but the supply services were inefficiently managed. Short of food, clothing, and supplies of all kinds, officers and men lived the best they could in hope that spring would bring a lessening of their trials. Two events of 1778 augured well for the future. One was the French alliance. The other was a reorganization of the army command that brought the appointments of Nathanael Greene as quartermaster general, of Jeremiah Wadsworth as commissary general, and of a new arrival, "Baron" Frederick von Steuben, as drillmaster. During the last months of the winter encampment at Valley Forge, Steuben's tactical instruction and a vast improvement in supply transformed the Continental Army into a formidable fighting force.

France's entry into the war convinced the British Government that Philadelphia could not be held. On June 18, Clinton, who had replaced Howe in the British command, began an overland retreat to New York. Washington immediately pursued and, on June 27, 1778, caught the British at Monmouth Courthouse. A smashing Continental victory was prevented by the misconduct of General Lee, who was subsequently court-martialed and suspended from command. Nevertheless, the Americans held their position against heavy counterattacks, and after dark the British retreated. (See pp. 115-117.)

In furtherance of the alliance, a French fleet with 4,000 regular troops reached America on July 8. Washington planned a joint attack on New York City, but the French ships were unable to cross the sandbar blocking the entrance to New York harbor. The American commander then persuaded the French to support an attack on the British garrison at Newport, R.I. An American Army under John Sullivan successfully landed on the island, but a gale scattered the French Fleet, which then sailed away and left Sullivan to extricate his men as best he could. The American Army was saved, but the affair severely strained relations between the allies.

|

| This fine old colonial mansion at Morristown, N.J., built just a few years earlier by Col. Jacob Ford, Jr., was Gen. George Washington's headquarters during the winter of 1779-80, while the Continental Army was encamped nearby in Jockey Hollow. Mrs. Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and other members of the staff resided here. (National Park Service) |

The war in the North settled into a stalemate after the abortive attack on Newport. The British held New York City and Newport, while Washington's army held a semicircular line around those cities. In the late spring of 1779, however, General Clinton sallied from the New York defenses to seize unfinished American works at Stony Point and Verlanck's Point, on opposite sides of the Hudson River below West Point. On the night of July 15, Gen. Anthony Wayne recaptured Stony Point in a daring attack at bayonet point. The Americans were unable to hold the position, but after its abandonment it was not reoccupied in strength by the British. (See pp. 133-135.) Washington's command remained near Morristown, N.J., in the following winter. (See pp. 58-59.) One further serious threat to Washington's position came in September 1780 with Benedict Arnold's treasonable plan to surrender West Point to the British. The plot was discovered and Arnold was forced to flee for his life.

Failure of the British to win a decision in the North caused them to turn their attention to the South, which had enjoyed 2 years of comparative calm. In the fall of 1778 the situation changed. Savannah fell to a British Army under Gen. Archibald Campbell in December, and the British quickly overran the interior of Georgia, occupying Augusta the following month. The invaders abandoned Augusta in February 1779, however, after a body of South Carolina Tories en route to reinforce them was crushed by American militia at Kettle Creek.

General Benjamin Lincoln was assigned to command American forces in South Carolina, but despite his vigilance the British, now under Gen. George Prevost, temporarily besieged Charleston in May. In the autumn of 1779, the arrival of a French Fleet under Adm. Count D'Estaing gave the Americans a temporary superiority of numbers, and General Lincoln attempted to recapture Savannah. After a 4-week siege, the combined French-American army assaulted the city on October 9. The attack was repulsed with heavy losses, including the brilliant Polish cavalryman, Casimir Pulaski; D'Estaing sailed away to the West Indies, and the Americans once more were on the defensive.

General Clinton sailed from New York early in 1780 with an expedition to capture Charleston. The British Army, outnumbering Lincoln more than 2 to 1, began siege operations on March 29. The American commander unwisely allowed himself to be bottled up in the city and on May 12 surrendered his army. This disaster left only one other organized American force in South Carolina—a small band of militia under Col. Abraham Buford. It was surprised and wiped out by Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton's British cavalry at Waxhaws on May 29. The British conquest of the South was nearly complete.

|

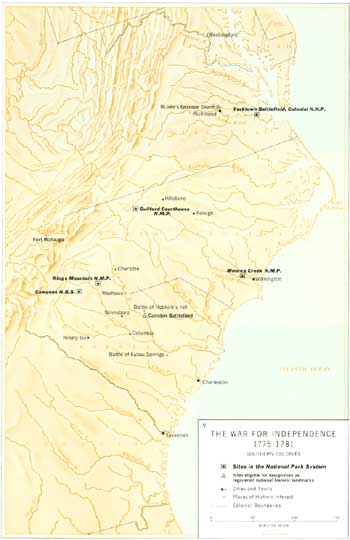

| Map V. The War for Independence, 1775-1781. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

When Charleston fell, a small force of Delaware and Maryland Continentals under Baron Johann Kalb had reached Virginia en route to reinforce Lincoln. Kalb advanced into North Carolina, where on July 25 General Gates appeared to take command. Gates almost immediately marched for the British base at Camden, S.C. Lord Cornwallis, commanding in South Carolina after Clinton's return to New York, reinforced Camden and took personal charge. The two armies met a few miles north of the town on August 16. The American Army was quickly routed and driven from the State in disorder. (See pp. 160-161.) The collapse of organized American resistance brought a period of bitter civil war to South Carolina, with highly effective partisan warfare waged by Col. Francis Marion and Gens. Thomas Sumter and Andrew Pickens.

|

| View from the eastern slope of the Kings Mountain ridge, looking north eastward toward Henry's Knob, another ridge of the Kings Mountain chain. (National Park Service) |

The defeat of Gates' army marked the nadir of American fortunes in the South. Within 2 months, however, the tide began to turn. In September Cornwallis invaded North Carolina, simultaneously sending Maj. Patrick Ferguson with his "American Volunteers" on a sweep through the back country of South Carolina. Ferguson's march aroused the Virginia and Carolina frontiersmen, who moved swiftly to surround and annihilate the Tories at Kings Mountain on October 7. (See pp. 71-72.) Cornwallis quickly withdrew from Charlotte, N.C., to Winnsboro, S.C.

|

| Granite obelisk erected in 1909 by the U.S. Government at Kings Mountain to commemorate the battle. (National Park Service) |

General Greene relieved Gates in command of the American Army in the South early in December 1780. He divided his army, to retain the initiative, advancing with one part against the British right flank at Camden and sending Gen. Daniel Morgan toward the British left at Ninety Six. Cornwallis divided his own army three ways, sending Tarleton after Morgan and reinforcing Camden, while with his main body he marched northward to cut the American supply line. Tarleton pushed forward with customary dash and came upon Morgan's men at the Cowpens on January 17, 1781. Tarleton flung his men upon the American line, and Morgan, in a tactical masterpiece, wiped out the attackers. Tarleton escaped with a few men, but his major usefulness had ended. Morgan quickly rejoined Greene, and the American Army began retreating northward. (See pp. 70-71.)

Cornwallis was sternly determined that Greene should not escape. Stripping his army of everything not essential, he marched swiftly in pursuit. Greene stayed just ahead of him, meanwhile actively encouraging the guerrilla leaders to harass the British rear and disrupt the supply lines. The Americans barely won the race for Virginia, crossing the swollen Dan River a few hours ahead of their pursuers. Having failed to catch Greene, Cornwallis withdrew to Hillsboro and sought to rebuild his depleted army. Greene received reinforcements and advanced on the British. At Guilford Courthouse, on March 15, the armies collided. Although the British retained possession of the field, Cornwallis was so badly shattered that he moved his army to Wilmington, on the coast, where the British Navy could support and supply it. (See pp. 63-64.)

|

| Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene was in command of American forces at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse. This engraving was made from a painting by Charles Willson Peale. (National Park Service) |

With Cornwallis out of the way, Greene returned to South Carolina. His ensuing operations were tactically unsuccessful. The Battle of Hobkirk's Hill on April 25 was an American defeat; the 4-week siege of Ninety Six ended in an American withdrawal when Lord Rawdon approached with British reinforcements; and the battle of Eutaw Springs on September 8, the last major engagement in South Carolina, ended indecisively. (See pp. 226, and 227-228.) Nevertheless, Greene's maneuvers resulted in strategic victory, clearing the British from the interior of South Carolina by the end of 1781. He was aided immensely in his campaign by the activities of the guerrilla leaders.

|

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/colonials-patriots/introj.htm

Last Updated: 09-Jan-2005