|

The Forest Service and The Civilian Conservation Corps: 1933-42

|

|

Appendix E:

Evaluation of CCC-Era Structures

This appendix is provided to assist the reader through the various procedures involved in the recording of CCC-era structures and features. Recommendations for determining significance are also included. Prior to any field investigation, it is most important to become familiar with the CCC architectural design philosophy. The best source for a summation is the USDA Forest Service Division of Engineering's "Acceptable Building Plans: Forest Service Administrative Buildings" compiled by Ellis Groben in 1938. All regional and supervisor's offices should retain copies of this manual.

"Acceptable Building Plans" consists of a written description of regional styles, site locations, orientation, building materials, and a series of existing and future building plans. Groben states in the foreword, "No matter how well buildings may be designed, with but few exceptions, they seldom enhance the beauty of their natural settings." He suggests, ". . . erecting only such structures as are absolutely essential . . . and then only of designs which harmonize with, or . . . are the least objectionable to nature's particular environment." This particular design philosophy is now referred to as non-intrusive architectural design.

Groben favored a regional style rather than a universal style. He claimed earlier building styles of the Forest Service failed to ". . . possess Forest Service identity or to adequately express its purposes." He encouraged each region to base its architectural styles upon "climatic considerations, vegetation and forest cover" and set forth this example to be used by the regions.

The following outline is helpful when attempting to identify various CCC sites:

| Type of country | Style of Architecture |

| Desert or semidesert | Adobe or pueblo |

| Grassland | Ranch-house type |

| Woodland—pine, fir, spruce | Timber type |

| Alpine | Alpine type (stone or stone and rough timbers) |

Another excellent resource is the "Recreation Plans Handbook" published by the Forest Service in 1936. It includes plans for recreational structures of all types and many existing resources can be traced to this handbook. Copies of this work should be obtained for consultation.

The aforementioned documents must be reviewed before researching any CCC site. Any existing plans will help document and add to the significance of a site evaluation. Whether such plans exist should be noted on the site inventory form.

Collecting information regarding any site can be as general or as detailed as is feasible. These guidelines are an attempt to make the recording process simple yet thorough enough to allow for an accurate evaluation. The CCC Site Inventory Form included here was designed for this purpose. Three categories of CCC sites should be noted: CCC campsites, CCC-built recreation sites, and CCC-built administrative sites. A list of building types found in each of the three categories is as follows:

CCC Campsites and Structures—Barracks, offices, tents and tent platforms, mess halls, kitchens, latrines, showers, infirmaries, educational buildings, recreation halls, pumphouses, garages, machine shops, blacksmith shops, barns, officer quarters, offices, dispensaries.

CCC-Built Recreation Areas—Tent camps/campgrounds, drinking fountains, fire pits, community kitchens, picnic shelters, tables, restrooms, bathhouses, swimming pools and lakes, beach areas, paths, footbridges. Organizational camps, mess halls, barracks, concession buildings, showers, playing fields, latrines, swimming pools. Trail shelters, trails, ski lodges, and warming huts.

CCC-Built Administrative Sites—Ranger stations, ranger's residences, assistant ranger's residences, crew residences, bunkhouses, offices, mess halls, pumphouses, garages, barns, blacksmith shops, machine shops, latrines. Lookout towers and houses, guard stations.

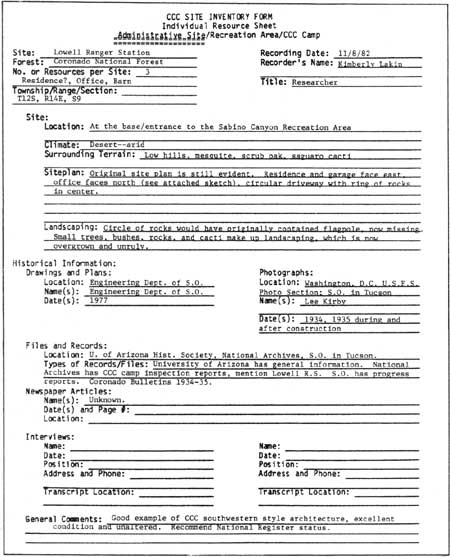

One of these three categories should be circled at the top of the form. The Lowell Ranger Station in Coronado National Forest and the Eagle Creek Campground in Mount Hood National Forest are used in figures 139 to 142 as examples to explain correct procedures. The general information sheet contains information about the site in general and the location of important historical materials (fig. 139):

Site

1. List the location, climate, and surrounding terrain in either a general or specific manner noting plant types, rock formation, and similar information of this nature.

2. Describe the original site plan and list any changes that have occurred. Describe the landscaping generally or specifically. Include a site plan.

Historical Information

1. If original drawings and plans exist, list location, name of architect/draftsman, and date. If originals cannot be located, list any later drawings or plans that exist and note location, name of architect/draftsman, and date.

2. If original photos exist, list their location, name of photographer, and date. Also specify any later photos that may document alterations or additions.

3. List the locations of various files and records that contain information concerning the site and describe the types of records, such as inspection reports, camp newspapers, correspondence, and interviews.

4. Give the name, date, and page number of any newspaper articles that mention the site.

5. List the names, dates, position, address, phone number, and transcript location of any person interviewed who discussed the site in an interview.

6. General comments might include the researcher's recommendations regarding the site and its significance in terms of National Register criteria.

|

| Figure 139—General information sheet of a CCC site inventory form. (Recorded by Kim Lakin, 1982) (click on image for a PDF version) |

Primary sources for historical information include correspondence, inspection reports, drawings, and plans found at ranger district offices and the divisions of engineering, information, and recreation in supervisors' offices. Historical societies and libraries own photographs, interviews, newspapers, diaries, maps, and memorabilia as part of their collections. The Photographic Section of the Forest Service in Washington, DC, is an excellent source for historical photographs. Their collection is cataloged by State and cross-indexed by subject on computer printouts. Retired Forest Service personnel may also have special knowledge or camp newspapers, photographs, and other documents. It is always helpful to interview an alumnus at the site because the setting often stimulates recollection.

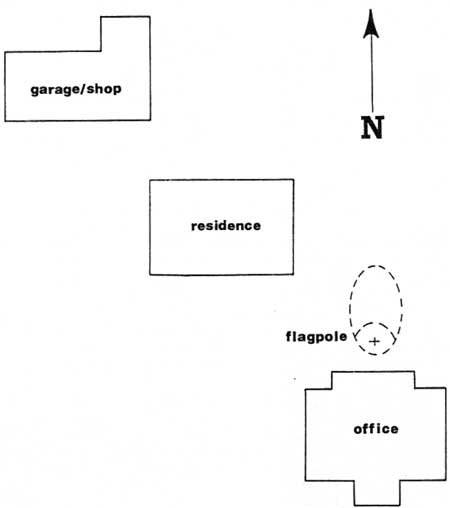

The second page of the CCC Site Inventory Form is the site plan (see fig. 140). This page should list the site name, person who sketched the plan, date, and scale of plan. The plan can be very simple, merely locating each structure or resource within the site boundaries. It should be detailed enough to include landscaping and measurements. North should always be at the top of the sheet and be indicated by a directional marker. Draw the site plan in pencil.

|

| Figure 140—Siteplan sheet of a CCC site inventory form. (Drawing by Kim Lakin, 1982) |

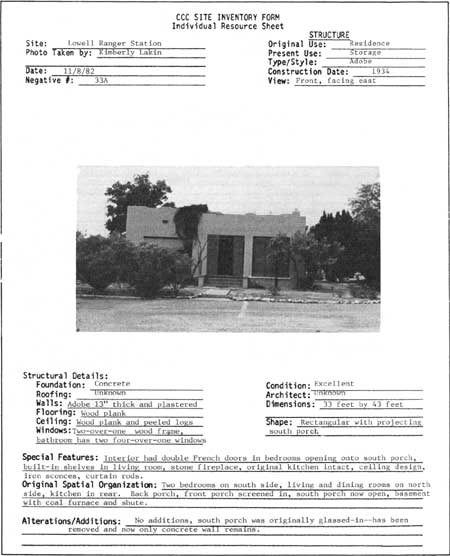

Include an individual resource sheet for each resource located on the site. Separate sheets have been developed for structures located on administrative sites or CCC camp sites and recreation areas. When working with structures, use the individual resource sheet labeled "Structure" and for a recreation area use the inventory sheet marked "Resource." Examples of both are included:

Individual Resource Sheet, Structure (fig. 141)

1. Fill out the general information at the top of the page. Include a 5 by 7 black and white photograph of the structure.

2. List the structural details of the building. Consult an architectural terminology glossary when in doubt about how to describe a particular detail. Identifying American Architecture by John J.G. Blumenson is helpful and easy to use.

3. Dimensions of the building should be noted. This can be done by consulting existing floor plans or by measuring the building with a tape measure.

4. The general shape should be noted. Is it square, rectangular, L-shaped, or some other configuration?

5. Describe the special features including any interior or exterior detail which may be unique or finely crafted.

6. Describe the original spatial organization if it still exists. If the building has been significantly altered inside, describe the alterations in the next space.

7. List any alterations or additions to the buildings and include dates, if known.

|

| Figure 141—Individual resource sheet for a structure. (Photo by Kim Lakin, 1982) (click on image for a PDF version) |

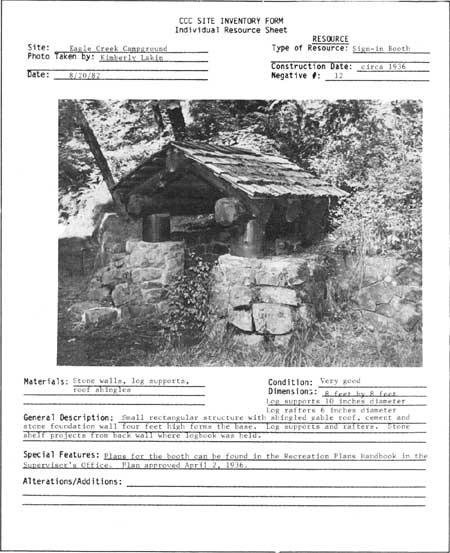

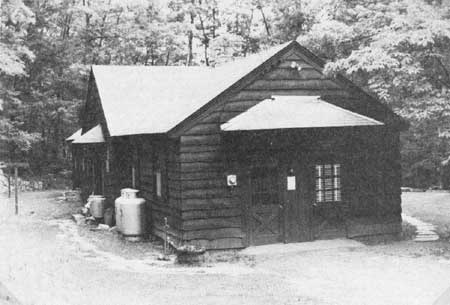

Individual Resource Sheet, Resource (fig. 142)

1. Use this sheet for resources such as bridges, paths, picnic tables, drinking fountains, picnic shelters, or any other resources located in recreation areas.

2. Fill out the information at the top of the page. List the type of feature. Include a 5 by 7 black and white photograph.

3. List all building materials including stone, brick, peeled logs, or lumber.

4. Give the condition and dimensions. Dimensions can be helpful especially with picnic shelters. Always include the circumference of the peeled logs. A measuring tape can be used to take dimensions of most features.

5. Give a general description.

6. List any special or unique aspects such as notching techniques, type of stone, and ornamentation. List any characteristics that distinguish the resource from others of the same type.

7. List any additions or alterations and give dates, if known. Examples of alterations include a bridge that has had concrete slabs added over the original stonework, windows cut into picnic shelter walls, or brickwork that has been repointed or stuccoed over.

|

| Figure 142—Individual resource sheet for a resource. (Photo by Kim Lakin, 1982) (click on image for a PDF version) |

Floor plans are an extremely helpful aid in evaluation. They are, however, time consuming, and if the structures have had alterations and additions, they can be difficult to render, A search should first be made for existing floor plans. Often the engineering department of the supervisor's office will have plans.

If floor plans do not exist, then the researcher must sketch these plans. It helps to have two to three people on a project, one for taking notes and the others for measuring. A tape measure and a surveyor's level are used for measurements. Basic measurements include shape, layout and location of doors, windows, and stairways. Be sure to indicate structural supports and each primary level of the building. The thickness of partitions, walls, and floors are measured and included in the final drawing. All measuring should be done with the tape at a constant height. If necessary, a level chalk line may be snapped along the walls as a guide. The team can measure each portion of the building, taking notes and sketching a rough plan. Later these notes can be compiled into a scaled floor plan. It is best to keep these plans to an 8-1/2- by 11-inch size unless a drafts-person is planning a full set of measured drawings.

If a full set of measured drawings is to be executed for a particular site, an excellent source is "Recording Historic Buildings" by Harley J. McKee, published in 1970, which gives a step-by-step description of procedures. If, however, this kind of intensive rendering cannot be done, a basic floor plan with some accurate measurements can add to the understanding of a structure. For features such as bridges and drinking fountains only a few basic measurements such as width and height are necessary. This information can be recorded on the individual resource page.

Evaluation Procedures—Since the National Historical Preservation Act of 1966, the Forest Service and other Federal agencies have been responsible for locating, identifying, protecting, and enhancing cultural resources on lands under their jurisdiction. Cultural resources are considered significant according to a set of criteria established by the National Register of Historic Places.

These criteria are:

The significance in American history, architecture, archeology and culture is present in districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects of State and local importance. Significance is determined by the extent to which these possess integrity of location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association and:

That are associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history; or

That are associated with the lives of persons significant in our past; or

That embody the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction, or that represent the work of a master, or that possess high artistic values, or that represent a significant and distinguishable entity whose components may lack individual distinction; or

That have yielded, or may be likely to yield, information important to prehistory or history.

The researcher should consider these elements when evaluating a site. Since many CCC era sites are less than 50 years old, they are often excluded from the National Register. Therefore, sites must be of exceptional importance to a community, region, State, or the Nation. The social, political, and economic impact of the Great Depression and the subsequent development of the CCC gives these sites an exceptional status. The nonintrusive design and certain construction techniques help establish the unique identity of buildings from this era.

The romantic ideal of incorporating traditional or native styles into the Forest Service architecture resulted in a distinctive building type belonging solely to the depression era. These native or traditional styles were imitated in a purely decorative sense. There was no intention on the part of the Forest Service and its architects to copy native or traditional construction techniques, but merely to give the appearance of something native or indigenous. In "Acceptable Building Plans," for example, Groben suggests the use of brick or hollow tile as a substitute for adobe, claiming it was "to all intents and purposes similar in architectural appearance to the traditional adobe prototypes."

As an example, the adobe ranger stations of the Coronado National Forests suggest the native architecture of the region but do not follow its construction techniques. The adobe bricks were made in the traditional manner, but the walls were held together with a lime mortar rather than mud. The walls were then plastered rather than using the traditional mud wall covering.

The tops of the CCC-built adobe structures were constructed of wood and covered with tar paper to achieve a parapet shape. The result was a squared-off version of the traditional adobe structures, which had rounded corners and roof lines (fig. 143).

|

| Figure 143—CCC-built adobe structure, Coronado National Forest, AZ. |

Another example of this striving for architectural appearance is the log construction of the CCC-built picnic structures following the traditional notching techniques. In many cases, however, metal tie rods and bolts were used rather than wooden pegs. Because the picnic shelter was a new building type, there were no hard-and-fast rules regarding construction or style. The Recreation Handbook carried several designs. Some of them employed traditional log construction techniques and others new designs and techniques. In some cases, a shelter's back walls were filled in with a series of upright logs (fig. 144), or the logs were stacked and notched. Sometimes they were not notched, but only stacked. Often these back walls have windows. Other shelters are open on all sides. Roofs vary between gables and hips. Logs are often used for railings, window sills, and lintels (fig. 145). Gable ends were either left open with a bracing system or filled with diagonal log patterns. Some shelters had gabled porch stoops. Others had fireplaces and built-in log picnic tables and benches.

|

| Figure 144—Back walls filled with upright logs, Bear Springs Picnic Shelter, Mount Hood National Forest, OR. (Photo by Dennis Egner, 1982) |

|

| Figure 145—Logs used as railings, window sills, and lintels, Bear Springs Picnic Shelter, Mount Hood National Forest, OR. (Photo by Dennis Egner, 1982) |

An especially distinctive picnic shelter is located in the Forest Service's intermountain region. It is constructed completely of whole aspen logs. The circular form recalls a gazebo. The wavy horizontal logs and the multitude of knots create a lyrical form. Obviously this structure was not based on traditional styles, but was built from the pure whim of the designer. The structure, however, achieves the "expression" of nature that Groben discusses; it uses the natural qualities of the aspen trees for its basis in design. The possibilities for the picnic shelter were endless, and perhaps no two shelters are exactly alike.

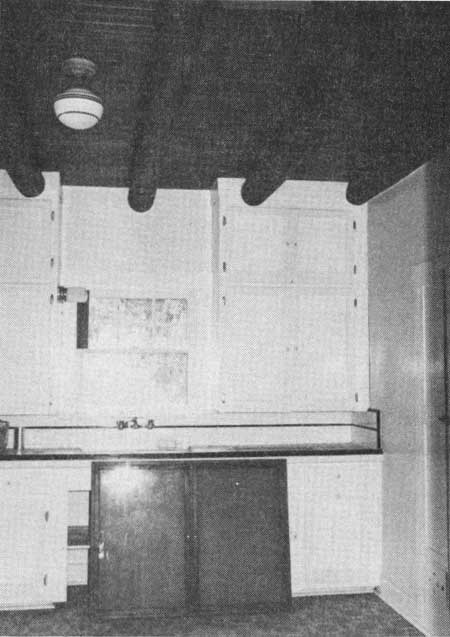

Administrative sites within the Mount Hood National Forest often have the half shake, half half-log siding, and the half-log portion being a paneling rather than true half logs. Another decorative rather than functional feature is the large, false exposed rafters under the eaves. The situation is reversed in the administrative buildings on the Coronado National Forest. Many of the buildings have the peeled log and wood or plaster ceilings, a typical Spanish feature, but the logs do not extend beyond the interior walls. Therefore, they do not follow through with the traditional function of the viga, which is to support the roof of the adobe building. Instead, this feature is purely decorative (fig. 146). Another example of the decorative, nonfunctional tendencies of this period are the rock or stone buildings in the Coronado National Forest that are actually frame buildings with a rock or stone veneer. Foundations were often concrete with a veneer of stone on the exterior to create the appearance of the traditional architecture.

|

| Figure 146—Interior ceiling view of the kitchen, showing decorative log rafters, residence, Lowell Ranger Station, Coronado National Forest, AZ. (Photo by Kim Lakin, 1982) |

This decorative rather than functional design element was carried over from the 1920's. The revival styles of the 1920's imitated earlier styles without reviving the earlier construction techniques. The most common example is the half-timbering of the English cottage, a prevalent style of the 1920's. The half-timbering was no longer a structural aspect of the building, but merely decorative. Although the CCC era did away with the "foreign styles" of the 1920's, they did not alter the basic concept, which was concerned primarily with appearance and not authenticity of structure or construction techniques. The Forest Service design philosophy of the 1930's created a completely new architectural style very loosely based on the traditional native styles of each region and even created styles imagined to be traditional in areas where there were no previous examples.

By the 1940's, this approach was viewed by some as ". . . an affectation, deliberate, and self-conscious, overly sophisticated, and romantic." The design emphasis had shifted to uniformity and functionalism, a philosophy that still exists today, partially as a result of the high cost of labor, but also because of a shift in basic design concepts. Because of this, the CCC-era structures must be considered unique to a particular period of American history.

Regional Evaluation—The unique design philosophy of the CCC era caused each region to develop within limits its own style or building type. Most likely each region will contain variations on two or more of the types listed in the "Acceptable Building Plans" manual. Because the regions employed their own staffs of architects and landscape architects, each region has characteristics distinct to that region even though the types may have been based on the "Acceptable Building Plans" examples. The following is a comparison of regional styles using the case study areas as examples.

Administrative Sites. Within the three case study areas it is easy to distinguish between the adobe type and the other types used for administration buildings, however, there are other distinctions as well. In addition to differences in building materials, there are also differences in overall shape and plan. The ranger station buildings on the Coronado National Forest are much smaller than those in the East and Northwest. Their shape is more square than rectangular. The buildings are almost always equipped with large front and back porches. The entire administrative compound is smaller, with only three or four buildings to a site. An exception is the Nogales Ranger Station, which is slightly larger.

Though George Washington National Forest has few administrative buildings compared to the other two areas, these few examples display a very different style from the wood buildings of the Northwest. Though the waney-edge siding is the most obvious difference, the general shape of the structure is different. The buildings are generally one story and rectangular in shape, with small front stoops (fig. 147). The roofline is a medium-pitched gable. George Washington National Forest does not have ranger station complexes, but occasionally an administrative building will be located within a recreation area. Thus the site for these buildings is quite different from the other two study areas, which contain full ranger station administrative sites having three or more buildings per site.

|

| Figure 147—Administration building (side view) built in 1933-34, Sherando Lake Recreation Area, George Washington National Forest, VA. (Photo by Alison T. Otis, 1982) |

In the Mount Hood National Forest, administrative buildings are often two-story with a steep pitched roof reminiscent of a Gothic roof line. The overall shape is a shorter rectangle with shakes and/or half-log siding. Porch stoops are built with peeled logs or squared porch posts with curving brackets. The ranger station sites here are quite large with as many as 10 to 20 buildings on one site.

Differences in terrain and environment are reflected in these buildings and sites similar to what Groben outlines in the "Acceptable Building Plans" manual. The long, medium-pitched buildings of the George Washington National Forest echo the gentle and deciduous forested mountains of the Virginia countryside. The steep roof lines of the buildings in the Mount Hood area blend with the tall Douglas-firs and rugged Cascade Mountains and protect the roofs from heavy snowfall as well. Flat roofs and adobe blend better with the desert environment than any wood structure.

Recreational Areas. Recreational sites also differ according to region. George Washington National Forest recreation sites tend to be large picnic or campground areas in grassy meadows and open spaces. Manmade swimming ponds and beaches, bathhouses, and large-scale picnic shelters with attached buildings are characteristic of this forest. The landscaping is carefully planned and well manicured. There are many recreation sites in this forest, and all are easily accessible from the nearby towns.

Very few recreation areas exist in the Coronado National Forest. Those that do exist are located close to major population centers such as the Sabino Canyon recreation area, just outside of Tucson. Because Sabino Canyon contains a water source, the vegetation is denser here than in other parts of the forest. Though the canyon is dry desert country with an abundance of rock and cacti, it is a gentle landscape surrounded by rolling hills. By building many of the structures and details such as the drinking fountains out of rock from the nearby hillsides, a marvelous connection between landscape and facilities was created. Bridges, firepits, and picnic tables look so much a part of their environment that in places they seem to grow out of it just like cacti.

The recreation areas in the Mount Hood National Forest are different from the other case study areas. The terrain in the lower portion of the forest is wet, and there is an abundance of moss and ground cover. Moss grows on the roofs of the picnic shelters and can cause structural damage. Higher up the mountain, the air is drier, there are more conifers and snow. Recreational structures must be built so their roofs will not collapse from the snow. Above timberline the structures are built with the rock from the ground and mountainsides (fig. 78). Picnic areas are more overgrown than those in the George Washington National Forest. There are no pools made for swimming, though there are lakes for fishing and skiing is available on Mount Hood. The picnic areas are smaller, but much more plentiful. Many have trails and paths through the forest. With the exception of the Eagle Creek campground, the camping/picnicking areas are smaller than the areas in George Washington National Forest or Coronado National Forest. Most often a single picnic shelter would accompany a campground or picnic area. One drinking fountain and several firepits are often in the area.

Camp Sites and Structures. Though the CCC camp sites and structures were planned to be standard and not distinctively related to the environment, certain features do vary according to region. For example, the type of wood used for building purposes varies from one region to the next. Coronado National Forest used lodge-pole pine from forests in the northern portion of Arizona. Lumber for structures in the Mount Hood National Forest was Douglas-fir, milled locally. The local mills bid on camp projects and whoever received the job adhered to strict instructions and specifications. The lumber was cut to order and included such items as the bolts for constructing the portable buildings. This stimulated the local economy and helped to avoid isolating a Federal government project from the inhabitants of nearby communities.

Another unique quality of each CCC campsite was landscaping and site planning. In many cases, the enrollees pitched in to landscape a camp in their free time. In almost all cases one or more of the men would enjoy caring for the grounds on a voluntary basis during off-hours.

The site plan was often determined by the environment. Some camps were located in canyons and confined by the steep rise of hills on either side, such as the Madera Canyon Camp on the Coronado National Forest. Other camps were surrounded by thick forests where only a bare minimum was cut for a CCC campsite, such as Camp Roosevelt in the George Washington National Forest.

Many campsites contained both the portable and rigid buildings. Determination of these two site types help in dating a site. This information can be determined through the use of existing records or by a physical search for the bolt system employed in the portable buildings. Often campsites will have unique building details such as the adobe recreation hall and kitchen at the Pena Blanca Camp in the Coronado National Forest.

The history and lore of each camp is as unique as the camp's relationship to the nearby population and the Forest Service personnel. Former enrollees have many stories to tell about the events and personal relationships within each camp. Tapes and transcripts of interviews add to the significance of each campsite.

Evaluation of Significance of Individual Sites—In addition to considering the unique qualities of the region, the researcher may also evaluate the site by comparing it to others of the same type. However, comparison of different types should be avoided. For example, the Lowell Ranger Station of the Coronado National Forest, an adobe type, could be compared to the Patagonia or Nogales Ranger Stations of the same forest or even a ranger station located in New Mexico or elsewhere if it were of the same general type. It would not be appropriate, however, to compare the Lowell Ranger Station to a ranger station located in the mountains of northern Arizona, which would be comparing an adobe type to a timber or alpine type.

The differences and similarities between CCC sites make sites both uniquely and collectively important. Therefore, there are certain elements to consider when examining these sites in relation to one another. Though regional distinctions are important, so are the distinctions within each forest. For example, consider the special features and unique elements of a site. Through the inventory process, these features should become evident, As individual craftsmen worked upon each site, each contained a quality different from other sites within the same region or even the same forest.

Conclusion—Researchers must first familiarize themselves with CCC-era history and design philosophy and gain an overall insight into the period. Then they can focus specifically on a given site. After inventory forms have been completed and drawings executed, an evaluation can be made. The researcher should consider the regional distinctions, the unique aspects of the individual forest, and finally the significant character of the site in relation to these other aspects. The National Register criteria should then be applied and the decision can be made for nomination of the site or structure. An example of a nomination form is included in appendix B.

Many forests need to decide how to manage these sites. By following a careful evaluation process, a determination can begin to be formulated. Some structures will merit nomination to the National Register whereas others will not. The decision as to the fate of the CCC sites and structures ultimately lies with each region and forest. It is therefore important that the Forest Service make every effort to collect all information relating to these sites for the correct decision to be made. Even when demolition is the only recourse, the sites should be fully recorded, including drawings, photographs, an inventory, historical information, interviews, and any other pertinent information. With this information, a complete record can be developed for a site, and new information can be added as it is discovered. In this manner, if a site no longer exists, the information collected may help another similar site to be preserved.

If a decision is made to preserve a site, there are several methods of preservation to follow. The minimum level of preservation is "stabilization," a process by which a site is stabilized from further deterioration, but is not restored or reconstructed in any way. This type of preservation may prove the best recourse when a site is considered significant but is in very poor condition, or if a site is considered less significant but is in fairly good condition.

"Rehabilitation" is a step above stabilization and is the most frequent method of preservation. A site will be rehabilitated to include some updating of certain elements, but all efforts are made to preserve the most significant aspects of the sites.

"Restoration" is the purest form of preservation and may be applied in cases where a site is in poor condition but is extremely significant. An intensive effort is made to restore the site to its original condition. This is the primary goal of restoration; function or use is secondary. A professional restoration job includes restoring sites using the original materials and construction techniques.

There are many details to consider before deciding upon any of these preservation methods. All three are legitimate solutions; however, a careful review of all three possibilities should be based on the evaluation of the site. Bear in mind the significance of all CCC-era sites and structures as they relate to the general design philosophy of that era. Compare the site to other similar sites in the Nation, State, region, and individual forest in order to help determine the significance.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> |

ccc/appe.htm

Last Updated: 07-Jan-2008