|

MOUNT McKINLEY

Guidebook 1940 |

|

| SEASON JUNE 10 TO SEPTEMBER 15 |

|

Mount McKinley NATIONAL PARK ALASKA |

||

|

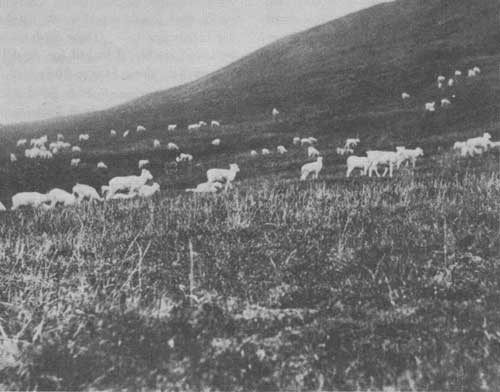

A DALL SHEEP Photo by Dixon

| ||||

MOUNT McKINLEY NATIONAL PARK, situated in south-central Alaska, was created by act of Congress approved February 26, 1917, and on January 30, 1922, was enlarged to 2,645 square miles. On March 19, 1932, Congress approved an extension on the north and east sides, enlarging it to its present area of 3,030 square miles.

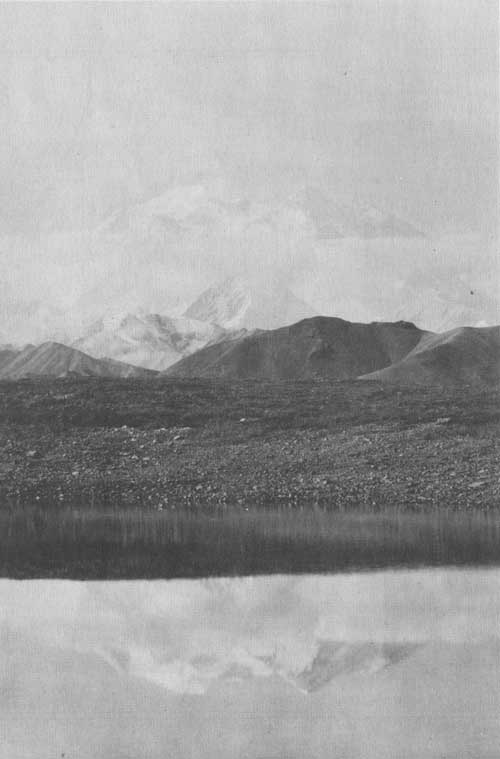

The principal scenic feature of the park is mighty Mount McKinley, the highest peak on the North American Continent. This majestic mountain rears its snow-covered head high into the clouds, reaching an altitude of 20,300 feet above sea level, and rises 17,000 feet above timber line. On its north and west sides McKinley rises abruptly from a plateau only 2,500 to 3,000 feet high. For two-thirds of the way down from its summit it is enveloped in snow throughout the year. Denali, "home of the sun," was the name given to this impressive snow-clad mountain by the early Indians.

Near Mount McKinley are Mount Foraker, with an elevation of 17,000 feet; Mount Hunter, 14,960 feet; and Mount Russell, rising 11,600 feet above sea level.

ASCENTS OF MOUNT McKINLEY

Mount McKinley is crowned by two peaks. The south pinnacle is 20,300 feet in altitude, and the north peak is only 300 feet lower. The first attempts to conquer the mountain were made in 1903, one party being under the leadership of Judge James Wickersham and the other headed by Dr. Frederick A. Cook; but neither was successful. In 1906 Cook made a second attempt which he claimed was crowned by success. In 1910, however, four "sourdoughs" who were not satisfied with Cook's story, undertook the climb, and two of them, Taylor and Anderson, reached the north peak. In 1912 a party under Dr. Herschel Parker and Belmore Brown succeeded in getting within a few hundred feet of the summit of the south peak.

On June 7, 1913, Archdeacon Hudson Stuck, Harry Karstens (later superintendent of the park), and two companions reached the summit of the south peak. They were the first men ever to achieve this goal. Nearly 19 years later, on May 7, 1932, a party composed of Alfred D. Lindley, Minneapolis attorney; Harry J. Lick, former superintendent of McKinley Park; Erling Strom, ski expert from Lake Placid, N. Y.; and Grant Pearson, a park ranger, accomplished the same feat. On May 9 they also climbed the north peak and achieved the distinction of becoming the first expedition to ascend both peaks of the great mountain.

GLACIERS FLOWING FROM ALASKA RANGE Photo by Bradford Washborn—Copyright, National Geographic Society |

GLACIERS

All of the largest northward-flowing glaciers of the Alaska Range rise on the ice-covered slopes of Mount McKinley and Mount Foraker. Of these the largest are the Herron, having its source in the névé fields of Mount Foraker; the Peters, which encircles the northwest end of Mount McKinley; and the Muldrow, whose front is about 15 miles northeast of Mount McKinley and whose source is in the unsurveyed heart of the range. The fronts of all these glaciers for a distance of one-fourth to one-half mile are deeply buried in rock debris. Along the crest line there are many smaller glaciers, including some of the hanging type.

The greatest glaciers of the Alaska Range are on its southern slope, which is exposed to the moisture-laden winds of the Pacific. The largest of the Pacific slope glaciers, however, lie in the basin of the Yentna and Chulitna Rivers. These have their source high up in the loftiest parts of the range and extend south far beyond the boundaries of the park.

The glaciers all appear to be retreating rapidly, but so far little direct proof has been obtained of the rate of recession. According to a rough estimate of geologists studying the area, the average annual recession of the Muldrow Glacier may be about one-tenth of a mile.

On the inland front but little morainic material is left along the old tracks of the glaciers, and it appears that most of the frontal debris is removed by the streams as fast as it is laid down. Such a process would be accelerated in this northern latitude by the freshets which accompany the spring breakup. The glaciers as a rule are not badly crevassed and many of them afford, beyond the frontal lobes, excellent routes of travel.

Most of the valleys and lowlands of the region were, during the Pleistocene period, filled with glacial ice. This ice also overrode some of the lower foothills, while in the high regions were the extensive névé fields which fed the ice streams.

MAMMALS AND BIRDS

As a park attraction, the animal life of Mount McKinley National Park is surpassed only by Denali itself. Up to September 1932, 112 kinds of birds and 34 kinds of mammals have been definitely identified within park boundaries. About 80 out of the total number of birds recorded are known to nest within the park. Nearly all of these breeding species may be found during the summer along the regular routes of travel.

Because of limited space, only a few outstanding species are listed here. Some of these, such as the willow ptarmigan and the caribou, are not found in any other national park; while the surfbird's eggs have been found in Mount McKinley National Park and nowhere else in the entire world.

CARIBOU.—Though many thousand caribou graze within McKinley Park, their roving disposition makes their whereabouts at any given time uncertain, and this feature imparts real zest to the quest of those who would seek them out. They travel singly, in pairs, or in small bands, while a herd of hundreds may be in one valley on a certain day and have vanished the next. Then, too, the search may lead anywhere from the low-lying barrens to the high steep ridges of the Alaska and Secondary Ranges.

Related to these North American caribou are the domesticated reindeer of "Santa Claus" fame, which are merely an Old World race which is smaller and darker than the caribou, with much shorter legs. These two are the only members of the deer family in which both sexes have antlers. Large brow tines, or "shovels," extend well forward over the nose, adding to the grotesque appearance of the huge antlers. Fair-sized caribou bulls stand about 4 feet at the shoulders and weigh about 300 pounds. Their color may be anywhere from sandy to golden brown, varying greatly with the individual. Both the neck and the hind quarters are lighter toned, giving the effect of a dark band across the middle.

Almost everywhere in the park the presence of caribou is indicated by the well-defined trails through the tundra or by certain battered willows which the animals have used for rubbing the velvet off their horns. Caribou also visit the licks, where their large, rounded, cowlike tracks give plain evidence of their visitations. When seen at a distance they are easily distinguishable from their associates, the mountain sheep, in that they are dark colored rather than whitish.

ALASKA MOOSE.—The Alaska moose is the largest animal found in Mount McKinley Park. It is, roughly, the size of a horse, large males weighing as much as a thousand pounds. It has the distinction of being the largest member of the deer family. In addition to this, the moose reaches its maximum size in Alaska. The males are distinguished by bearing broadly palmated antlers, which grow to tremendous size, some having a spread of over 63 inches. Both sexes carry a "bell" or "dewlap" on the throat; this peculiar appendage is merely a loose, pendant fold of skin, which hangs down several inches at the middle of the throat. The moose is an ungainly creature, with a muscular, overhanging muzzle, which, together with the high shoulders (which may have a height as great as 7 feet 8 inches from the ground) and the sloping hind quarters, gives the animal a rather grotesque appearance.

In color the Alaska moose ranges from pale russet brown to almost black, becoming lighter on the belly and underparts. At a distance, the moose appears to be a dark-colored animal—darker, in fact, than the caribou. The young moose when first born are buffy brown in color, without spots. A single moose is the usual offspring; sometimes twins are born.

During the warm summer months the cow moose with their young calves are most likely to be encountered along the willow thickets high up in the mountain passes. During the winter time moose are found in the heavier-timbered areas along the lower streams in the park.

MOUNTAIN SHEEP—ABOUT 3,000 LIVE IN THE PARK

ALASKA MOUNTAIN SHEEP.—The white Alaska mountain sheep are among the handsomest game animals of the Mount McKinley region and the most fascinating to pursue and observe. Perhaps no other locality presents such abundant opportunity for their study in large numbers at close range. Two important distinguishing characteristics of this species are the white color and relatively slender, spreading horns. In contrast, the mountain sheep of the United States have a sandy-brown color, while the horns are heavy and closely curled. A good-size ram of the Alaska sheep will stand about 39 inches at the shoulders and weigh approximately 200 pounds.

The single young is born during early May in sheltered nooks under protecting cliffs. Frequently twins occur. Though soon able to follow their mothers about, the lambs spend the first few weeks of their lives close to easy concealment in the rocks, against the appearance of golden eagles, wolves, wolverines, or other enemies. By June they dare to venture out on the grassy slopes where they may be seen scampering about in little bands of 4 to 10 under the watchful eye of some old ewe. Playing follow-the-leader over the rocks and steep places, they gain practice in the agility and sure-footedness so necessary to their existence. A lamb can easily negotiate a vertical jump of 6 feet.

In the latter part of June there is a general migration across to the main Alaska Range. Among the best places to see large bands of sheep during the tourist season are the headwaters of the Savage River and above the pass at Double Mountain. Here they mingle freely with the caribou, the two ruminants grazing together and using the same trails.

TOKLAT GRIZZLY BEAR.—To watch a Toklat grizzly bear in his native habitat in Mount McKinley Park is to enjoy one of the rarest treats which the park affords. Formerly grizzly bears were not uncommon along the higher open ridges above timber line at the head of the Toklat River. But because of their destruction by prospectors, who claim that they destroy the caches (stored food supplies of miners and other men who live in the region), these bears have become greatly reduced in numbers. They were found to be relatively rare in 1926, when the region was surveyed by a biologist. The most conspicuous evidence of the presence of grizzly bears is to be found in the numerous small, craterlike holes which dot the ridges along the headwaters of the Savage, the Sanctuary, and the Toklat Rivers. These miniature craters are merely holes left where grizzly bears have dug out ground squirrels, which form their chief food supply.

Other animals commonly seen are the red fox, hoary marmot, parka squirrel, and porcupine. Wolverine, lynx, wolf, coyote, beaver, marten, mink, snowshoe rabbit and Alaska cony are also in the park.

SHORT-BILLED GULL.—Visitors to the McKinley district frequently express surprise at the number of "sea gulls" that breed there, over 300 miles inland, far removed from the salt water of the seacoast. The common gull of the McKinley region is the short-billed, although a few of the larger herring gulls are also present. The latter species may easily be recognized by its great size. The short-billed gull is of medium size, having a length, from tip of tail to end of bill, of 17 or 18 inches. These birds are pure white below, while the mantle is pearl gray. The bill is clear yellow, without any decided spot or ring. The feet are also yellow, tinged with olive.

ALASKA WILLOW PTARMIGAN.—The Alaska willow ptarmigan is one of the noteworthy birds of Mount McKinley Park. Since willow ptarmigan do not occur in any of our other national parks, they should especially be sought for by visitors here. These birds may be found readily, if looked for, in willow thickets along Savage River.

The willow ptarmigan is an Arctic grouse which turns white in winter and brown in summer. In size it is about equal to the ruffed grouse of the eastern United States. By the time visitors begin to arrive in the park in early June, the male ptarmigan have started to acquire their brown summer dress. At this time, which is the mating season, the brown-backed cock birds with white wings and underparts and orange red combs over their eyes may often be seen beside the road leading into the park. When flushed the males fly up with rapid strokes of their white wings and with hoarse cackles of alarm. This characteristic "crowing" of the cock ptarmigan often awakens the visitor at midnight or in the early morning hours.

THE ELUSIVE SURFBIRD

SURFBIRD.—The surfbird is the most distinguished as well as the most elusive avian citizen of Mount McKinley National Park. For nearly 150 years, since the species was first given its scientific name, its nest and eggs remained unknown. The surfbird winters in South America as far south as the Strait of Magellan. It breeds among the mountain tops of central Alaska. Twice each year, in migration, it traverses the Pacific coast of North and South America.

Joseph Dixon, formerly of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology of the University of California, and now associated with the National Park Service as field naturalist, has been a member of five expeditions to Alaska. During each of these trips the unknown nest and eggs of the surfbird were diligently sought, but continued search produced only negative results. On May 28, 1926, the first and only nest of this rare bird known to science was discovered and recorded by Mr. Dixon and George Wright (The Condor, vol. XXIX, pp. 3-16, January 1927). The natives of Alaska had a legend that the surfbird lays its eggs "on the bare mountains in the interior." For those who are keenly interested in bird life, to catch a glimpse of the elusive surfbird, or, better yet, to find its nest, will mark the achievement of the rarest ornithological experience that the park has to offer.

TREES AND PLANTS

The black spruce, with its somber foliage and clusters of tawny cones, is the commonest evergreen tree in the park.

The graceful white birch is found in the lower valleys. The cottonwoods and the quaking aspen are near the streams. The willows are abundant, ranging from small trees in favorable localities through the shrublike forms, until they dwindle to matlike growths on the mountain slopes. To escape the rigors of the climate, these latter hide their tortuous woody stems underground, thrusting only the catkins of their flowers and a few conspicuously net-veined leaves to the surface during the brief summer. The erect dark-red catkins of dwarf willow are common near Savage River.

SHRUBS.—The thickets which clothe the valleys and the lower slopes of the mountains are composed of many varieties of shrubs, principally the dwarf birch, or "Buckbrush," a dull green in summer but flaming scarlet and orange at the touch of frost. The shrubbery cinquefoil shows bright-yellow butter cuplike flowers. The blueberry yields berries that are an important source of food to Indian and white man alike. The woolly Labrador-tea has rusty underleaf surfaces and clusters of snow-white flowers, as has the spirea. The bearberry grows in dense thickets and shows glandular dotted leaves and crimsonberries. The only prickly shrub in the park is the lovely wild rose. This is especially abundant near the park entrance.

HERBACEOUS PLANTS.—Scattered through the thicketed growth are the delicately tinted pink and blue heads of valerian and the drooping bells, ranging in color from deepest pink to palest blue, of the bluebells, also known as chiming bells or languid ladies. As the summer advances, the large-flowered blue larkspur and the monkshood thrust their showy blossoms above the thicket growth.

In the shade of the spruces, the broad white bracts of the low bunch-berry or dogwood glimmer in the early part of the season, while in the fall they show bunches of bright redberries. The delicate pink bells of the twin flower cover the old mossy logs, and the crowberry, with its tiny awl-shaped needles and shiny blackberries, twines through the moss and lichens. Diminutive pyrolas in white and pink space their waxy bells along their stems.

Near the park entrance and at most lower altitudes the fireweed covers all otherwise unoccupied space with its sheet of bright pink flowers. Only occasionally does one find the tall fumitory with its finely divided leaves and lyre-shaped and yellow-tipped pink blossoms.

In the sandy river bed and along the roadside the large-flowered water willow herb flames bright cerise, and the lemon-yellow arctic poppy grows in scattered clumps. A number of leguminous plants populate the sandy bars, the purple vetch being the most conspicuous.

Farther up the valley a knotweed with large rose-pink spikes is abundant and contrasts sharply with the fragrant deep-blue forget-me-not, the Territorial flower.

Beds of the beautiful little shooting stars occur in damp spaces, and on the drier slopes there grow great carpets of the wood dryas, with white flowers somewhat resembling strawberry blossoms. There is also a yellow variety. When the petals fall they are succeeded by a tuft of silvery seed plumes and are often found covering acres of the sandy gravel bars as well as the mountain slopes. The foliage is the favorite food of the mountain sheep during the winter season.

CLIMATE

The climate of Mount McKinley National Park differs on the two sides of the Alaska Range. On the inland side of the mountains there are short, comparatively warm summers and long, cold winters, with low precipitation. The area draining into the Pacific enjoys a more equable climate, the summers being longer and cooler and the winters warmer than in the interior, with much greater precipitation.

The average snowfall in winter varies from 30 to 45 inches during the whole of the season, while in the summer the total precipitation never amounts to more than 15 inches. Temperatures range from 60° to 80° in the summer, and in the winter, although at times the thermometer reaches 45° and 50° below zero, it usually averages 5° to 10° below.

During the summer months the sun shines more than 18 hours a day. On June 21, the longest day in the year, the sun is visible at midnight from the top of mountains approximately 4,000 feet high, and photographs may be taken at that time. In Fairbanks this occasion is usually celebrated by a midnight sun festival, with a baseball game as one of the athletic events.

Winter in this park has unique charm, which appeals to the hardy adventurer. It is first announced by the flaming colors made by the frost-touched alder, cottonwood, willow, and quaking aspen. In contrast to these are the great masses of dark green spruce and the sphagnum mosses above timber line. Access to practically all portions of the park can be had by dog team during the long Arctic winter, when an indescribable stillness hovers over everything.

FISHING

The grayling, a very hardy species, is found in park waters. They are sporty fish and weigh 1 to 2 pounds. There are also trout in some of the park streams which are classified locally as Dolly Varden. Their weight is in the neighborhood of 1 pound. At Wonder Lake, about 35 miles due north of Mount McKinley, there are Mackinaw trout.

ROADS AND TRAILS

There are now 89 miles of excellent gravel highway within the park. This road begins at McKinley Park Station on the Alaska Railroad at an elevation of 1,732 feet above sea level.

The road continues through the park, past Sanctuary River, Igloo Creek, Sable Pass, East Fork River, Polychronic Pass, Toklat River, Highway Pass, Stony Creek, Stony Hill, Thorofare Pass, Camp Eielson at Mile 66, and Wonder Lake, passing out of the park at Moose Creek and ending at Eureka, where there are extensive placer and quartz gold mining operations. From many points along the road, visitors have excellent views of Mount McKinley and other peaks, as well as of some of the smaller active glaciers; and animals are always seen.

From Wonder Lake or Mount Eielson a saddle-horse trail leads across the McKinley River to the head of the Clearwater River and to the western portion of the park, where excellent views of Mount McKinley, Mount Foraker, and other massive peaks may be obtained. Interesting saddle-horse trips of shorter duration may also be arranged.

RANGER ON WINTER-PATROL DUTY

ADMINISTRATION

Mount McKinley National Park is administered by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior. The officer in immediate charge is Frank T. Been, superintendent. All complaints and suggestions regarding service in the park should be addressed to him. The post office address is McKinley Park, Alaska.

Park headquarters is located at Mile 2 on the highway.

The official park season is from June 10 to September 15. During this time the public utilities are operated.

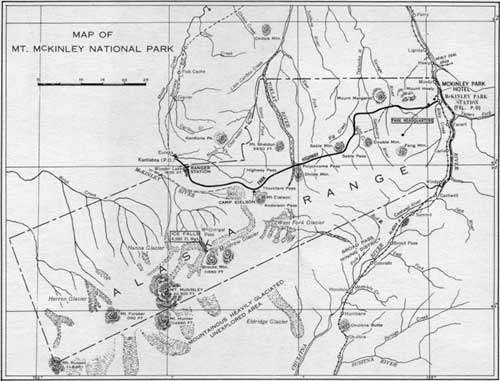

MAP OF MT. McKINLEY NATIONAL PARK (click on image for a PDF version) |

HOW TO REACH THE PARK

The entrance to Mount McKinley National Park is at McKinley Park Station, a point on the Alaska Railroad, 348 miles from Seward, the seaport terminus, and 123 miles from Fairbanks, the metropolis of interior Alaska. Five trains a week arrive from these cities.

Steamers of the Alaska Steamship, Pacific Steamship, Canadian Pacific, and Canadian National Railways Cos. sail weekly for Alaska. These steamers ply between Seattle and Valdez and Seward, and also between Seattle and Nome, with the exception of the Canadian boats, which go only as far as Skagway. Information relative to travel and suggested loop trips may be obtained from the Superintendent, Mount McKinley National Park, Alaska, and the offices of steamship companies and travel agencies.

MOUNT MCKINLEY AND REFLECTION IN WONDER LAKE

ACCOMMODATIONS

Mount McKinley Park Hotel, operated by the Alaska Railroad, is close to the railroad station so that visitors have convenient access to the modern and largest hotel in Alaska.

Camp Eielson, a tourist tent camp, operated by the Mount McKinley Tourist and Transportation Co., is 66 miles from the railroad station and is reached by bus over the park highway. Here the most spectacular views of Mount McKinley are gained and may be seen in full light almost any time during the 24-hour day.

Pack trips and horseback trips may be arranged with the Transportation Company.

Airplanes are widely used in Alaska. Hence, a flight over Mount McKinley and the park can be readily arranged with the Transportation Company.

Schedule of rates may be obtained and reservations made by writing to the Alaska Railroad, Chicago, Illinois, or Anchorage, Alaska; and to Mount McKinley Tourist and Transportation Co., Fairbanks, Alaska.

VISITORS STARTING FROM HOTEL FOR BUS TRIP THROUGH PARK

RULES AND REGULATIONS

[Briefed]

THE PARK REGULATIONS are designed for the protection of the natural beauties and scenery as well as for the comfort and convenience of visitors. Complete regulations may be examined at the office of the superintendent of the park. The following synopsis is for the general guidance of visitors, who are requested to assist in the administration of the park by observing the rules.

The destruction, defacement, or disturbance of buildings, signs, equipment, or other property, or of trees, flowers, vegetation, or other natural conditions and curiosities is prohibited.

Camping with tents is permitted. When in the vicinity of designated camp sites these sites must be used. Only dead and down timber should be used for fuel. All refuse should be burned or buried.

Fires shall be lighted only when necessary, and when no longer needed shall be completely extinguished. They shall not be built in duff or a location where a conflagration may result. No lighted cigar, cigarette, or other burning material shall be dropped in any grass, twigs, leaves, or tree mold.

All hunting, killing, wounding, frightening, capturing, or attempting to capture any wild bird or animal is prohibited. Firearms are prohibited in the park except with the permission of the superintendent.

Fishing in any manner other than with hook and line is prohibited. Fishing in particular waters may be suspended by the superintendent.

Cameras may be freely used in the park for general scenic picture purposes.

Gambling in any form or the operation of gambling devices, whether for merchandise or otherwise, is prohibited.

Private notices or advertisements shall not be posted or displayed in the park, excepting such as the superintendent deems necessary for the convenience and guidance of the public.

Dogs are not permitted in the park, except by special permission of the superintendent.

Mountain climbing shall be undertaken only with permission of the superintendent.

The penalty for violation of the rules and regulations is a fine of not more than $500, or imprisonment not exceeding 6 months, or both, together with all costs of the proceedings.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> |

1940/dena/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010