|

YOSEMITE

Rules and Regulations 1920 |

|

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK.

GENERAL DESCRIPTION.

THE Yosemite National Park is much greater, both in area and beauty, than is generally known. Nearly all Americans who have not explored it consider it identical with the far-famed Yosemite Valley. The fact is that the valley is a very small part, indeed, of this glorious public pleasure ground.

It was established October 1, 1890, but its boundary lines were changed in several important respects in 1905 and 1906. It now has an area of 1,125 square miles, or 719,622 acres.

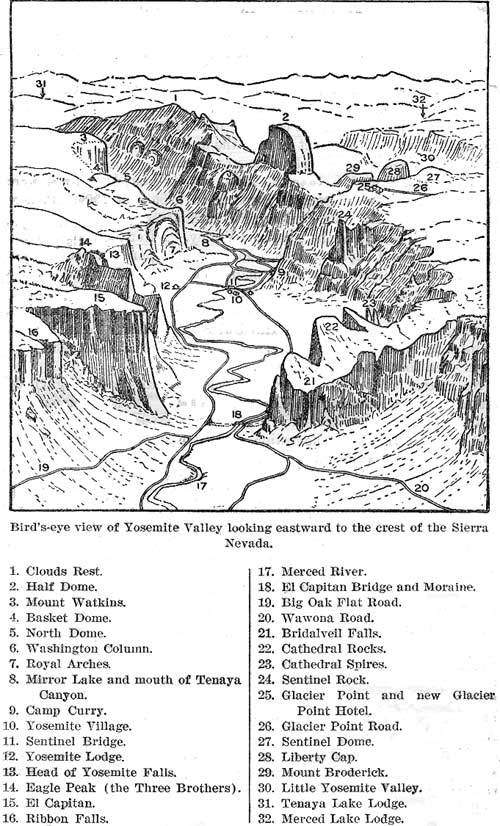

Little need be said of the Yosemite Valley. After these many years of visitation and exploration it remains imcomparable. It is often said that the Sierras contain "many Yosemites," but there is no other of its superabundance of sheer beauty. It has been so celebrated in book and magazine and newspaper that the Three Brothers, El Capitan, Bridalveil Fall, Cathedral Spires, Mirror Lake, Glacier Point, and all the rest are old familiar friends to millions who have never seen them except in picture.

No matter what their expectation, most visitors are delightfully astonished upon entering the Yosemite Valley. The sheer immensity of the precipices on either side of the valley's peaceful floor; the loftiness and the romantic suggestion of the numerous waterfalls; the majesty of the granite walls; and the unreal, almost fairy quality of the ever-varying whole, can not be successfully foretold.

For the rest, the park includes, in John Muir's words, "the headwaters of the Tuolumne and Merced Rivers, two of the most songful streams in the world; innumerable lakes and waterfalls and smooth silky lawns; the noblest forests, the loftiest granite domes, the deepest ice-sculptured canyons, the brightest crystalline pavements, and snowy mountains soaring into the sky twelve and thirteen thousand feet, arrayed in open ranks and spiry pinnacled groups partially separated by tremendous canyons and amphitheaters; gardens on their sunny brows, avalanches thundering down their long white slopes, cataracts roaring gray and foaming in the crooked rugged gorges, and glaciers in their shadowy recesses working in silence, slowly completing their sculptures; new-born lakes at their feet, blue and green, free or encumbered with drifting icebergs like miniature Arctic Oceans. shining, sparkling, calm as stars."

This land of enchantments is a land of enchanted climate. Its summers are warm, but not too warm; dry, but not too dry; its nights cold and marvelously starry.

Rain seldom falls in the Yosemite between May and October.

THE VALLEY INCOMPARABLE.

After the visitor has recovered from his first shock of astonishment—for it is no less—at the beauty of the valley, inevitably he wonders how nature made it. How did it happen that walls so enormous rose so nearly perpendicular from so level a floor?

It will not lessen wonder to learn that it was water which cut in the solid granite most of this deep valley. Originally the Merced flowed practically at the level of the canyon top. How long it took its waters, enormous in volume then, no doubt, and rushing swiftly down a steep-pitched course, to scrape out this canyon with its tools of sand and rock, no man can guess. And, as it cut the valley, it left the tributary streams sloping ever more sharply from their levels until eventually they poured over brinks as giant waterfalls.

But geologists have determined, by unerring fact, that the river did by far the most of the work, and that the great glacier which followed the water ages afterward did little more than square its corners and steepen its cliffs. It may have increased the depth from several hundred to a thousand feet, not more.

During the uncountable years since the glaciers vanished, erosion has again marvelously used its wonder chisel. With the lessening of the Merced's volume, the effect was no longer to deepen the channel but to amazingly carve and decorate the walls.

YOSEMITE IN SPRING.

Spring in Yosemite is most refreshing and exhilarating. It rarely rains and is seldom even cloudy. The falls are at their best; the azalea bushes, which grow to man's height, blossom forth in flowers exquisite as orchids. The latter part of April or the early part of May the lodges and camps are opened, tents are pitched along the river, and before one knows it summer has arrived.

YOSEMITE IN SUMMER.

This is the season with which visitors are most familiar. This is the vacation period, and Yosemite has an irresistible appeal. There is every form of enjoyment available. One may live in a lodge, where the honk of an automobile is never heard and where a full day's catch of trout is assured from near-by lake or stream; one may live in a hotel where mountain scenery is unsurpassed; or one may live in the valley and enjoy swimming, dancing, tennis, and other forms of entertainment.

YOSEMITE IN AUTUMN.

Autumn is intensified in the Yosemite. The changing leaves make a riot of color. Albert, King of the Belgians, and party spent two days in Yosemite National Park in October, 1919. The King and Queen and others of the party rode horseback to Glacier Point and stayed overnight, and then motored to the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees. Crown Prince Leopold, accompanied by a park ranger as guide, camped out under the stars in the high country, joining the royal party at the Big Trees. Their enthusiasm for the park at this season was unbounded.

YOSEMITE IN WINTER.

Yosemite winters are mild and balmy, the granite walls inclosing and protecting the valley. Due to the high walls there are two distinct winter climates on opposite sides of the valley, the north side being many degrees warmer than the south side. The first snow flies early in December, transforming the valley into a white fairyland. The sunset paints the cliffs and domes with rosy alpine glow.

One may ride horseback and motor on the valley floor, and skating, tobogganing, sleighing, and other winter sports are increasing in popularity.

John Muir, in describing the ice cone of the Yosemite Falls, writes: "The frozen spray (of the falls) give rise to one of the most interesting winter features of the valley—a cone of ice at the foot of the falls 400 or 500 feet high. * * * When the cone is in the process of formation, growing higher and wider in frosty weather, it looks like a beautiful smooth, pure white hill."

Even Californians have hardly awakened to the fact that at the very gate of their orange orchards is Yosemite Valley, as beautiful in winter as the Alps.

SPECTACULAR WATERFALLS.

The depth to which the valley was scooped is measured roughly by the extraordinary height of the waterfalls which pour over the rim, though it must he remembered that doubtless these, too, may have cut their channels hundreds of feet deeper than their original levels.

The Yosemite Falls, for instance, drop 1,430 feet in one sheer fall, a height equal to nine Niagara Falls piled one on top of the other. The Lower Yosemite Fall, immediately below, has a drop of 320 feet, or two Niagaras more. Vernal Falls has the same height, while Illilouette Falls is 50 feet higher. The Nevada Falls drops 594 feet sheer; the celebrated Bridalveil Fall, 620 feet; while the Ribbon Falls, highest of all, drops 1,612 feet sheer, a straight fall nearly ten times as great as Niagara. Nowhere else in the world may be had a water spectacle such as this.

Similarly the sheer summits. Cathedral Rocks rise 2,591 feet vertically from the valley: El Capitan, 3,604 feet; Sentinel Dome, 4,157 feet; Half Dome, 4,892 feet; Clouds Rest, 5,964 feet.

Among these monsters the Merced sings its winding way.

The falls are at their fullest in May and June while the winter snows are melting. They are still full in July, but after that decrease rapidly in volume. But let it not be supposed that the beauty of the falls depends upon the amount of water that pours over their brinks. It is true that the May rush of water over the Yosemite Falls is even a little appalling; that the ground sometimes trembles with it half a mile away. But it is equally true that the Yosemite Falls in late August, when, in specially dry seasons, much of the water reaches the bottom of the upper falls in the form of mist, that the spectacle possesses a filmy grandeur that is not comparable probably with any other sight in the world. The one inspires by sheer bulk and power; the other uplifts by its intangible spirit of beauty.

ABOVE THE VALLEY'S RIM.

The Yosemite Valley occupies 8 square miles out of a total of more than 1,100 square miles in the Yosemite National Park. The park above the rim is less celebrated principally because it is less known. It is less known principally because it was never, until 1915, opened to the public by road. And even now, except for several leading into the valley, there are only two roads above the rim. Of these only one crosses the park from side to side.

This magnificent pleasure land lies on the west slope of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The crest of the range is its eastern boundary as far south as Mount Lyell. The rivers which water it originate in the everlasting snows. A thousand icy streams converge to form them. They flow west through a marvelous sea of peaks, resting by the way in hundreds of snow-bordered lakes, romping through luxuriant valleys, rushing turbulently over rocky heights, swinging in and out of the shadows of mighty mountains.

Glacier Point commands a magnificent view of the High Sierra. Spread before one in panorama are the domes, the pinnacles, the waterfalls, and dominating all, Half Dome, mythical seat of an Indian maiden. A few steps from the hotel one looks down into Yosemite Valley, 3,254 feet below, where automobiles are but moving specks, tents white dots, and the Merced River a silver tracery on green velvet.

It is a land of sunshine; it almost never rains. It is a land of inspiring, often sublime, scenery. It is the ideal camping-out ground.

THE TIOGA ROAD.

From east to west across this mountain-top paradise winds the Tioga Road, connecting on the west with the main road system of California and crossing the Sierra on the east through Tioga Pass. The road has a romantic history. It was built by Chinese labor in 1881 to a gold mine east of the park, but, as the mine did not pay the expenses of getting out the ore, it was quickly abandoned and soon became impassable. In 1915 a group of public-spirited citizens purchased it from the present owners of the old mining property and presented it to the Government. It has been placed again in good repair.

When a young man, Mark Twain visited Mono Lake on the Tioga Road. Following is his own inimitable description from "Roughing It."

"Mono Lake is a hundred miles in a straight line from the ocean—and between it and the ocean are one or two ranges of mountains—yet thousands of sea gulls go there every season to lay their eggs and rear their young. One would as soon expect to find sea gulls in Kansas. And in this connection let us observe another instance of nature's wisdom. The islands in the lake being merely huge masses of lava, coated over with ashes and pumice stone, and utterly innocent of vegetation or anything that would burn; and sea gulls' eggs being entirely useless to anybody unless they be cooked, nature has provided an unfailing spring of boiling water on the largest island, and you can put your eggs in there, and in four minutes you can boil them as hard as any statement I have made during the past 15 years. Within 10 feet of the boiling spring is a spring of pure cold water, sweet and wholesome. So, in that island you get your board and washing free of charge—and if nature had gone further and furnished a nice American hotel clerk, who was crusty and disobliging, and didn't know anything about the time-tables, or the railroad routes—or—anything—and was proud of it—I would not wish for a more desirable boarding house."

The Tioga Road opens another and highly scenic highway across the Sierra. It also opens the Yosemite for the first time to direct approach from east of the Sierra. By connecting the northern half of the park with the automobile system in the valley it makes possible a rapid development.

THE VALLEY OF THE TUOLUMNE.

Rising in snow-clad monster mountains of the northwest, the Tuolumne River follows a tumultuous course, a few miles north of the Tioga Road, westward across the park. As a stream it is next in importance to the Merced. Its Waterwheel Falls are the coming wonder of scenic America—coming, because the trail that will make them known has only recently been completed. Its Grand Canyon will stand high among America's scenic canyons when it becomes known. Its valley, the Hetch Hetchy, has been a celebrity for some years.

"It is the heart of the high Sierra," writes John Muir, "8,500 to 9,000 feet above the level of the sea. The gray, picturesque Cathedral Range bounds it on the south; a similar range or spur, the highest peak of which is Mount Conness, on the north; the noble Mounts Dana, Gibbs, Mammoth, Lyell, McClure, and others on the axis of the range on the east; a heavy billowy crowd of glacier-polished rocks and Mount Hoffman on the west. Down through the open, sunny meadow levels of the valley flows the Tuolumne River, fresh, and cool from its many glacial fountains, the highest of which are the glaciers that lie on the north side of Mount Lyell and Mount McClure."

Of the grand canyon of the Tuolumne, Muir writes: "It is the cascades or sloping falls on the main river that are the crowning glory of the canyon, and these, in volume, extent, and variety, surpass those of any other canyon in the Sierra. The most showy and interesting of them are mostly in the upper part of the canyon above the point of entrance of Cathedral Creek and Hoffman Creek. For miles the river is one wild, exulting, on-rushing mass of snowy purple bloom, spreading over glacial waves of granite without any definite channel, gliding in magnificent silver plumes, dashing and foaming through huge bowlder dams, leaping high in the air in wheellike whirls, displaying glorious enthusiasm, tossing from side to side, doubling, glinting, singing in exuberance of mountain energy."

THE WATERWHEEL FALLS.

Muir's "wheellike whirls" undoubtedly mean the soon-to-be celebrated Waterwheel Falls. Rushing down the canyon's slanting granites under great headway, the river encounters shelves of rock projecting from its bottom. From these are thrown up enormous arcs of solid water high in air. Some of the waterwheels rise 50 feet and span 80 feet in the arc.

The spectacle is extraordinary in character and quite unequaled in beauty. Nevertheless, before the trail was built so difficult was the going that probably only a few hundred persons all told had ever seen these waterwheels.

North of the Tuolumne River is an enormous area of lakes and valleys which are seldom visited, notwithstanding that it is fairly penetrated by trails. It is a wilderness of wonderful charm and deserves to harbor a thousand camps. The trouting in many of these waters is unsurpassed.

Though unknown to people generally, this superb Yosemite country north of the valley has been the haunt for many years of the confirmed mountain lovers of the Pacific coast. It has been the favorite resort of the Sierra Club for 15 years of summer outings. The fishing is exceptionally fine.

THE MOUNTAIN CLIMAX OF THE SIERRA.

The monster mountain mass of which Mount Lyell is the chief lies on the southwest boundary of the park. It may be reached by trail from Tuolumne Meadows and is well worth the journey. It is the climax of the Sierra in this neighborhood.

The traveler swings from the Tuolumne Meadows around Johnston Peak to Lyell Fork, and turns southward up its valley. Rafferty Peak and Parsons Peak rear gray heads on the right, and huge Kuna Crest borders the trail's left side for miles. At the head of the valley, beyond several immense granite shelves, rears the mighty group, Mount Lyell in the center, supported on the north by McClure Mountain and on the south by Rodgers Peak.

The way up is through a vast basin of tumbled granite, encircled at its climax by a titanic rampart of nine sharp, glistening peaks and hundreds of spearlike points, the whole cloaked in enormous, sweeping shrouds of snow. Presently the granite spurs inclose you. And presently, beyond these, looms a mighty wall of glistening granite which apparently forbids further approach to the mountain's shrine. But another half hour brings you face to face with Lyell's rugged top and shining glaciers, one of the noblest high places in America.

MERCED AND WASHBURN LAKES.

The waters from the western slopes of Lyell and McClure find their way, through many streams and many lakelets of splendid beauty, into two lakes which are the headwaters of the famous Merced River. The upper of these is Washburn Lake, cradled in bare heights and celebrated for its fishing. This is the formal source of the Merced. Several miles below the river rests again in beautiful Merced Lake.

There is an excellent camp at the head of Merced Lake, and a fine trail to the Yosemite Valley which crosses glacier-polished slopes. There is unusual fishing. It is really the wilderness.

THE BIG TREES.

The greatest grove of giant sequoia trees outside of the Sequoia National Park is found in the extreme south of the Yosemite National Park. It is called the Mariposa Grove. Most persons who have seen sequoia trees have seen them here. It is reached from the Wawona Road, which enters the park from the south. To see this grove requires a day's trip from the Yosemite Valley and back.

Some of these sequoia trees are the largest and the oldest living things.

"A tree that has lived 500 years," writes Ellsworth Huntington in Harper's Magazine, "is still in its early youth; one that has rounded out a thousand summers and winters is only in full maturity; and old age, the threescore years and ten of the sequoias, does not come for 17 or 18 centuries. How old the oldest trees may be is not yet certain, but I have counted the rings of 79 that were over 2,000 years of age, of 3 that were over 3,000, and of 1 that was 3,150. In the days of the Trojan War and of the exodus of the Hebrews from Egypt this oldest tree was a sturdy sapling with stiff, prickly foliage like that of a cedar, but far more compressed."

The monster tree of the Mariposa Grove is the Grizzly Giant, whose girth is 93 feet, whose diameter is 29.6 feet, and whose height is 204 feet. It is probably a little short of 4,000 years old. Sawed into inch boards, this tree would box the greatest steamship ever built and put a lid on the box. If its trunk were cut through, a wagon and two street cars could drive through side by side and still leave the sides strong enough to support the tree. There is no way in which one can really appreciate its size and majesty except by looking upon it.

It is the third largest tree in the world. The largest and oldest is the General Sherman tree in the Sequoia National Park, whose height is 280 feet and whose diameter is 36.5 feet. The second largest is the General Grant tree, in the General Grant National Park, whose height is 264 feet and whose diameter is 35 feet.

Other trees in the Mariposa Grove, which have become more or less celebrated individually, are the Washington tree, whose diameter is only 3 inches less than that of the Grizzly Giant; the Columbia tree, whose height is 294 feet; and the Wawona tree, through whose trunk runs an automobile road 26 feet wide.

There are two minor sequoia groves in the Yosemite National Park—the Merced and the Tuolumne.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

1920/yose/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 16-Feb-2010