|

YELLOWSTONE

Rules and Regulations 1920 |

|

YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK.

GENERAL DESCRIPTION.

The Yellowstone National Park was created by the act of March 1, 1872. It is approximately 62 miles long and 54 miles wide, giving an area of 3,348 square miles, or 2,142,720 acres. It is under the control and supervision of the National Park Service of the Interior Department.

The Yellowstone is probably the best known of our National Parks. Its geysers are celebrated the world over because, for size, power, and variety of action, as well as number, the region has no competitor. New Zealand, which ranks second, and Iceland, where the word "geyser" originated, possess the only other geyser basins of prominence, but both together do not offer the visitor what he may see in two or three days in Yellowstone. Indeed, the spectacle is one of extraordinary novelty. There are few spots in this world where one is so strongly possessed by emotions of wonder and mystery. The visitor is powerfully impressed by a sense of nearness to nature's secret laboratories.

The Yellowstone National Park is located in northwestern Wyoming, encroaching slightly upon Montana and Idaho.1 It is our largest national park. The central portion is essentially a broad, elevated, volcanic plateau, between 7,000 and 8,500 feet above sea level, and with an average elevation of about 8,000 feet. Surrounding it on the south, east, north, and northwest are mountain ranges with culminating peaks and ridges rising from 2,000 to 4,000 feet above the general level of the inclosed table-land.

1Of the park area, 3,114 square miles, or 1,992,960 acres, are within the state of Wyoming, 198 square miles, or 126,720 acres, within the state of Montana, and 36 square miles, or 23,040 acres, within the State of Idaho.

The entire region is volcanic. Not only the surrounding mountains but the great interior plain is made of material once ejected, as ash and lava, from depths far below the surface. Geological speculation points to a crater which doubtless once opened just west of Mount Washburn. Looked down upon from Washburn's summit and examined from the main road north of the pass, the conformation of the foreground and of the distant mountains is suggestive even to the unscientific eye.

In addition to these specultive appearances, positive evidence of Yellowstone's volcanic origin is apparent to all in the black glass of Obsidian Cliff, the whorled and contorted lavas along the road near the top of Mount Washburn, and the fused and oxydized colored sands in the sides and depths of the Grand Canyon.

THE GEYSERS.

There are five active geyser basins, the Norris, the Lower, the Upper, the Heart Lake, and Shoshone Basins, all lying in the west and south central parts of the park. The geysers exhibit a large variety of character and action. Some, like Old Faithful, spout at quite regular intervals, longer or shorter. Others are irregular. Some burst upward with immense power. Others shoot streams at angles or bubble and foam in action.

Geysers are, roughly speaking, water volcanoes. They occur only at places where the internal heat of the earth approaches close to the surface. Their action, for so many years unexplained. and even now regarded with wonder by so many, is simple. Water from the surface trickling through cracks in the rocks, or water from subterranean springs collecting in the bottom of the geyser's crater, down among the strata of intense heat, becomes itself intensely heated and gives off steam, which expands and forces upward the cooler water that lies above it.

It is then that the water at the surface of the geyser begins to bubble and give off clouds of steam, the sign to the watchers above that the geyser is about to play.

At last the water in the bottom reaches so great an expansion under continued heat that the less heated water above can no longer weigh it down, so it bursts upward with great violence, rising many feet in the air and continuing to play until practically all the water in the crater has been expelled. The water, cooled and falling back to the ground, again seeps through the surface to gather as before in the crater's depth, and in a greater or less time, according to difficulties in the way of its return, becomes reheated to the bursting point, when the geyser spouts again.

One may readily make a geyser in any laboratory with a test tube, a little water, and a Bunsen burner. A mimic geyser was made in the laboratory of the Department of the Interior in the winter of 1915, which when in action plays at regular intervals of a minute and a quarter. The water is heated in a metal bulb, and finds its way to the surface vent through a spiral rubber tube. When it plays the water rises 3 or 4 feet in height, varying according to the intensity of the heat applied at the bulb.

The water finds its way back by an iron pipe into the bulb, when presently it again becomes heated and discharges itself.

OTHER HOT-WATER PHENOMENA.

Nearly the entire Yellowstone region is remarkable for its hot-water phenomena. The more prominent geysers are confined to three basins lying near each other in the middle west side of the park, but other hot-water manifestations occur at more widely separated points. Marvelously colored hot springs, mud volcanoes, and other strange phenomena are frequent. At Mammoth, at Norris, and at Thumb the hot water has brought to the surface quantities of white mineral deposits which build terraces of beautifully incrusted basins high up into the air, often engulfing trees of considerable size. Over the edges of these carved basins pour the hot water. Microscopic plants called algae grow on the edges and sides of these basins, painting them hues of red and pink and bluish gray, which glow brilliantly. At many other points lesser hot springs occur, introducing strange, almost uncanny, elements into wooded and otherwise quite normal landscapes.

A tour of these hot-water formations and spouting geysers is an experience never to be forgotten. Some of the geysers play at quite regular intervals. For mnny years the celebrated Old Faithful has played with average regularity every 70 minutes; some of the largest geysers play at irregular intervals of days, weeks, or months. Some very small ones play every few minutes. Many bubbling hot springs, which throw water 2 or 3 feet into the air once or twice a minute, are really small, imperfectly formed geysers.

The hot-spring terraces are also a rather awe-inspiring spectacle when seen for the first time. The visitor may climb upon them and pick his way around among the steaming pools. In certain lights the surface of these pools appears vividly colored. The deeper hot pools are often intensely green. The incrustations are often beautifully crystallized. Clumps of grass, and even flowers, which have been submerged in the charged waters, become exquisitely plated, as if with frosted silver.

GRAND CANYON OF THE YELLOWSTONE

But the geysers and hot-water formations are by no means the only wonders in the Yellowstone. Indeed the entire park is a wonderland. The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone affords a spectacle worthy of a national park were there no geysers. But the Grand Canyons, of which there are several in our wonderful western country are not to be confused. Of these, by far the largest and most impressive is the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River in Arizona. That is the one always meant when people speak of visiting "The Grand Canyon," without designating a location. It is the giant of canyons.

The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone is altogether different. Great though its size, it is much the smaller of the two. What makes it a scenic feature of the first order is its really marvelous coloring. It is the cameo of canyons.

Standing upon Inspiration Point, which pushes out almost to the center of the canyon, one seems to look almost vertically down upon the foaming Yellowstone River. To the south a waterfall twice the height of Niagara rushes seemingly out of the pine-clad hills and pours downward to be lost again in green. From that point 2 or 3 miles to where you stand and beneath you widens out the most glorious kaleidoscope of color you will ever see in nature. The steep slopes, dropping on either side a thousand feet and more from the pine-topped levels above, are inconceivably carved and fretted by the frost and the erosion of the ages. Sometimes they lie in straight lines at easy angles, from which jut high rocky prominences. Sometimes they lie in huge hollows carved from the side walls. Here and there jagged rocky needles rise perpendicularly for hundreds of feet like groups of gothic spires.

And the whole is colored as brokenly and vividly as the field of a kaleidoscope. The whole is streaked and spotted and stratified in every shade from the deepest orange to the faintest lemon; from deep crimson through all the brick shades to the softest pink; from black through all the grays and pearls to glistening white. The greens are furnished by the dark pines above, the lighter shades of growth caught here and there in soft masses on the gentler slopes and the foaming green of the plunging river so far below. The blues, ever changing, are found in the dome of the sky overhead.

It is a spectacle which one looks upon in silence.

There are several spots from which fine partial views may be had but no person can say he has seen the canyon who has not stood upon Inspiration Point.

DUNRAVEN PASS AND TOWER FALLS.

From the canyon the visitor follows the road northward to Mammoth and views some of the most inspiring scenery in America. The crossing of Dunraven Pass and the ascent of Mount Washburn are events which will linger long in vivid memory.

A few miles farther north, where the road again finds the shore of the Yellowstone River, scenery which has few equals is encountered at Tower Falls. The river's gorge at this point, the falls of Tower Creek, and the ramparts of rock far above the foaming Yellowstone are romantic to a high degree.

REMARKABLE FOSSIL FORESTS.

The fossil forests of the Yellowstone National Park cover an extensive area in the northern portion of the park, being especially abundant along the west side of Lamar River for about 20 miles above its junction with the Yellowstone. Here the land rises rather abruptly to a height of approximately 2,000 feet above the valley floor. It is known locally as Specimen Ridge, and forms an approach to Amethyst Mountain.

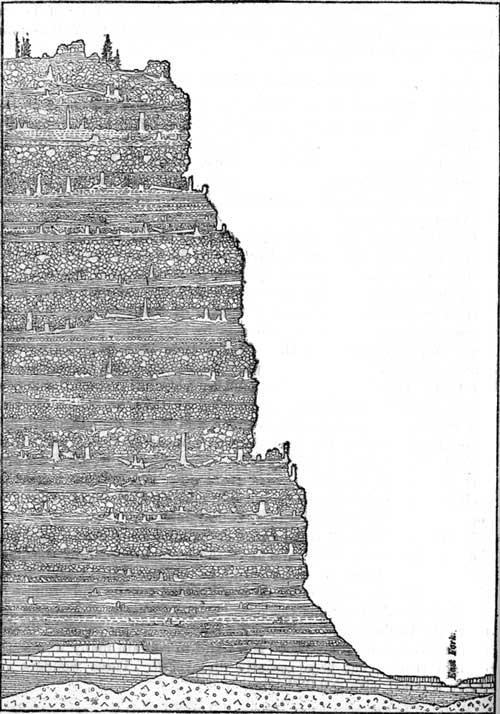

One traversing the valley of the Lamar River may see at many places numerous upright fossil trunks in the faces of nearly vertical walls. These trunks are not all at a particular level but occur at irregular heights; in fact a section cut down through these 2,000 feet of beds would disclose a succession of fossil forests, as in the accompanying illustration. That is to say, after the first forest grew and was entombed, there was a time without volcanic outburst—a period long enough to permit a second forest to grow above the first. This in turn was covered by volcanic material and preserved, to be followed again by a period of quiet, and these more or less regular alternations of volcanism and forest growth continued throughout the time the beds were in process of formation. Geological changes are excessively slow. No geologist would dare predict that, a few thousand years from now, the present forests of Yellowstone Park may not lie buried under another layer of lava on top of which may flourish a new Yellowstone.

There is also a small fossil forest containing a number of standing trunks near Tower Falls, and near the eastern border of the park along Lamar River in the vicinity of Cache, Calfee, and Miller Creeks there are many more or less isolated trunks and stumps of fossil trees. Just outside the park, in the Gallatin Mountains, between the Gallatin and Yellowstone Rivers, another petrified forest, said to cover more than 35,000 acres and to contain many wonderful upright trunks, has been recently discovered. These wonders are easily reached with saddle horses.

GREATEST WILD-ANIMAL REFUGE.

The Yellowstone National Park is the largest and most successful wild-animal refuge in the world. It is also, for this reason, the best and most accessible field for nature study.

|

| IDEAL SECTION THROUGH 2,000 FEET OF BEDS OF SPECIMEN RIDGE, SHOWING SUCCESSION OF BURIED FORESTS. AFTER HOLMES. |

Its 3,300 square miles of mountains and valleys remain nearly as nature made them, for the 200 miles of roads and the four hotels and many camps are as nothing in this immense wilderness. No tree has been cut except when absolutely necessary for road or trail or camp. No herds invade its valleys. Visitors for the most part keep to the beaten road, and the wild animals have learned in the years that they mean them no harm. To be sure they are not always seen by the people in the automobile stages which whirl from point to point daily during the season; but the quiet watcher on the trails may see deer and bear and elk and antelope to his heart's content, and he may even see mountain sheep, moose, and bison by journeying on foot or by horseback into their distant retreats. In the fall and spring when the crowds are absent, wild deer gather in great numbers at the hotel clearings to crop the grass, and the children feed them flowers. One of the diversions at the road builders' camps in the wilderness is cultivating the acquaintance of the animals.

Thus one of the most interesting lessons from the Yellowstone is that wild animals are fearful and dangerous only when men treat them as game or as enemies.

BEARS.

Even the big grizzlies, which are generally believed to be ferocious, are proved by our national parks' experience to be inoffensive if not attacked. When attacked they become dangerous, indeed. It is contrary to the regulations of the park to molest or feed the bears.

The brown, cinnamon, and black bears, which, by the way, are the same species only differently colored—the blondes and brunettes, so to speak, of the same bear family—are playful, comparatively fearless, sometimes even friendly. They are greedy fellows, and steal camp supplies whenever they can.

This wild-animal paradise contains more than 30,000 elk, several hundred moose, innumerable deer, many antelope, and a large and increasing herd of bison.

It is an excellent bird preserve also; 200 species live natural, undisturbed lives. Eagles are found among the crags. Wild geese and ducks are found in profusion. Many hundreds of large white pelicans add to the picturesqueness of Yellowstone Lake.

TROUT FISHING.

Trout fishing in Yellowstone waters is unexcelled. All three of the great watersheds abound in trout, which often attain large size. Yellowstone Lake is the home of large trout, which are taken freely from boats, and the Yellowstone River and its tributaries yield excellent catches to the skillful angler.

The Madison River and its tributaries also abound in trout, and Michigan grayling are to be caught in the northwestern streams.

There is excellent fishing also in many of the lesser lakes. Detailed information concerning fishing is found, beginning on page —.

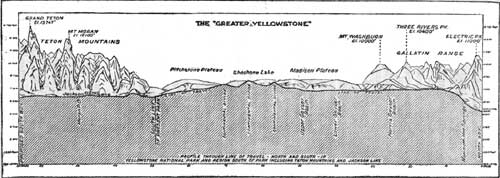

THE GREATER YELLOWSTONE.

The criticism often made by persons who have visited granite countries that the Yellowstone region lacks the supreme grandeur of some others of our national parks will cease to have weight when the magnificent Teton Mountains just south of the southern boundary are added to the park. These mountains begin at the foot of the Pitchstone Plateau a mile or two below the southern gateway and extend south and west. They border Jackson Lake on its west side, rising rapidly in a series of remarkably toothed and jagged peaks until they reach a sublime climax, 30 miles south of the park, in the Grand Teton, which rises cathedrallike to an altitude of 13,747 feet.

This whole amazing outcropping of gigantic granite peaks is in many respects the most imposing, as certainly it is the most extraordinary massing of mountain spires in America. It leaps more than 7,000 feet apparently vertically from the lake and plain. Seen from the road at Moran, where the Snake River escapes from the reclamation dam which pens flood waters within Jackson Lake for the benefit of farms in arid western lands, these mountains seem actually to border the lake's west shore. It is hard to realize that these stupendous creations of the Master Architect, bearing upon their shoulders many glistening glaciers, are 9 miles away.

Jackson Hole, as this country has been known for many years, was the last refuge of the desperado of the picturesque era of our western life. Here, until comparatively recent years, the bank robber of the city, the highwayman of the plains, the "bad man" of the frontier, the hostile Indian, and the hunted murderer found safe retreat. In these rolling, partly wooded plains and the foothills and canyons of these tremendous mountains even military pursuers were baffled. Here for years they lived in safety on the enormous elk herds of the neighborhood and raided distant countrysides at leisure.

With their passing and the partial protection of the game Jackson Hole entered upon its final destiny, that of contributing to the pleasure and inspiration of a great and peaceful people. The very contrast between its gigantic granite spires and the beautiful plateau and fruitful farms farther to the south is an element of charm.

These amazing mountains are, from their nature, a component part of the Yellowstone National Park, whose gamut of majestic scenery they complete, and no doubt would have been included within its original boundaries had their supreme magnificence been then appreciated. Already Yellowstone visitors have claimed it, and automobile stages run to Moran and back on regular schedule. In time, no doubt, part of it will be added formally to the park territory.

|

|

THE "GREATER YELLOWSTONE" (click on image for a PDF version) |

THE RED CANYON OF THE SHOSHONE.

Jackson Hole is not the only spectacle of magnificence intimately associated with Yellowstone but lying without its borders. Eastward through picturesque Sylvan Pass, well across the park boundary, the road passes through a red-walled canyon so vividly colored and so remarkably carved by the frosts and the rains of ages that its passage imprints itself indelibly upon memory. It is no wonder that a hundred fantastic names have been fastened upon these fantastic rock shapes silhouetted against the sky.

And miles farther on, where the united forks of the Shoshone won a precipitous way through enormous walls of rock, the Shoshone Dam, the second highest in the world, higher than New York's famous Flatiron Building, holds back for irrigation a large and deep lake of water and creates, through partnership of man and nature, a spectacle of grandeur perhaps unequaled of its kind. The road, which shelves and tunnels down the canyon, forcing a division of space with the imprisoned river, is one of the sensational runs of the West.

THE TRAIL SYSTEM.

The motorization of Yellowstone National Park, which is now complete, by reducing greatly the time formerly required to travel from scenic spot to scenic spot, permits the tourist to spend a far greater proportion of his allowance of time in pleasurable sight-seeing. It has also brought to the park many thousands of more or less leisurely motorists in their own cars, many of whom bring with them their own camping-out equipment. The day of the new Yellowstone, of Yellowstone the vacation land, has dawned.

To fill these new needs, the National Park Service is developing the trail system as rapidly as time and appropriations permit. Much has already been accomplished, and several hundred miles of fairly good trails are now available for the horseback rider and hiker. These trails lead into the great scenic sections of the park, out to streams and lakes teeming with fish, far away into the foothills of the Absaroka Range where the wild buffalo browse, into the petrified forests and other regions of strange geological formations, out beyond the north boundary to picturesque old mining camps, and they afford park tours touching the same important points of interest that the road system includes, although sections of the roads must be used in these circle tours. If parties wish to travel on the trails without the service of a guide, careful inquiries should be made at the office of the superintendent or at the nearest ranger station before starting, and a good map should be procured and studied. The map in the center of this booklet merely sketches the trail system. On this map the trails are printed in green. On pages 55 to 60 the reader will find an outline of the important trail trips.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

1920/yell/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 16-Feb-2010