|

ROCKY MOUNTAIN

Rules and Regulations 1920 |

|

SEEING ROCKY MOUNTAIN.

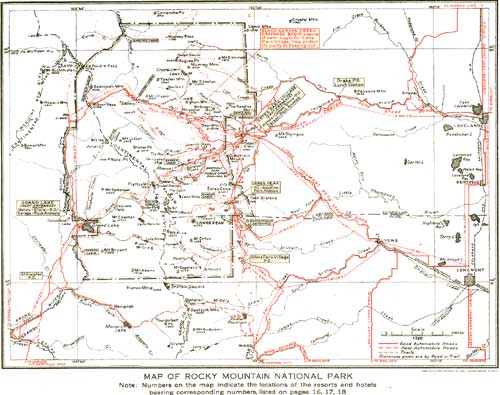

The visitor purposing to see Rocky Mountain National Park should bear in mind a few general outlines. The national park boundary lies about a mile west of Estes Park village. The main range carries the Continental Divide lengthwise in a direction irregularly west of north; while in the northeast the Mummy Mountains mass superbly.

On the east side, from the village of Estes Park a road runs south through and skirting the park and eventually finding a way to Denver, via Ward or Lyons; from Estes Park also a new road follows Fall River far up into the mountains, which, when finished, will cross the Divide and join the west side road. Other roads penetrate Horseshoe Park, Moraine Park, Bartholf Park, and other broad valleys within the Rocky Mountain National Park, where hotels and camps abound. One road leads to Sprague's, a convenient starting point for Glacier Gorge, Loch Vale, Bear Lake, and Flattop Trail. Another leads to the several excellent resorts of Moraine Park, convenient starting places for Fern and Odessa Lakes, Trail Ridge, and Flattop Trail. Along the Fall River road are several houses which are convenient starting places for Lawn Lake and the Mummy Mountains. In the south of the park are several hotels on or near the road which are convenient starting places for Longs Peak. A comfortable lodge at Copeland Lake on the main road is a convenient starting place for the Wild Basin.

On the west side, from Grand Lake, a road runs south to Granby; also north up the east bank of the Grand River to Squeaky Bobs and beyond. It is this road which will connect, below Milners Pass, with the Fall River road. At Grand Lake an excellent road partly encircles the lake. From it trails penetrate the wilderness to various points under and over the Continental Divide. Grand Lake is the western terminus of the Flattop Trail to Estes Park.

The important first step for the visitor who wants to understand and enjoy Rocky Mountain National Park is to secure a Government contour map and learn how to read it. Everything, then, including elevations, even of the valleys, is plain reading. The map may be had from the superintendent in Estes Park, or from the United States Geological Survey, Washington, D. C.

GUIDES.

Travelers on trails are earnestly advised to secure the services of licensed guides for all except the shortest trips. Besides insuring security the guide adds greatly to one's comfort and enjoyment. He knows the country and its features of interest, and also has a general knowledge of the trees and wild flowers. Information as to guides can be secured from the superintendent of the park.

THE FLATTOP TRAIL.

The principal trail, because the only one which crosses the Continental Divide in direct line between Estes Park on the east and Grand Lake on the west, is the Flattop Trail. The trip may be made on horseback in either direction in one day, but it takes an accustomed trail traveler to do it with pleasure. The average tourist who wishes to enjoy the trip and really see the heart of the Rockies in passing had better spend the night in one of the hotels in Moraine or Bartholf Park and make an early start from there.

From either place the trail leads quickly to the steep eastern slope of Flattop Mountain, up which it zigzags among tremendous granite bowlders, offering at every turn ever widening and lengthening views of the precipitous faces of these spirelike cliffs and of the superlatively beautiful country lying on the east.

There is little that is wilder in this land than the eastern face of Flattop Mountain. The trail winds under and then over enormous bowlders; it skirts well-like abysses; it fronts distant views of wonderful variety; it develops remarkable profiles of Longs Peak. At one turn the traveler looks perpendicularly down 1,000 feet into Dream Lake.

For awhile the trail skirts the edge of Tyndall Gorge and looks across the vast bed of the glacier to the rugged peak of Hallett. It rounds the perpetual snows topping the cirque of Tyndall Glacier, a favorite resort of ptarmigan. It looks backward and downward upon the flat mile-wide top of the mighty moraine of ancient days in the middle of which Bierstadt Lake shines, jewel-like, in a setting of pines. It bewilders with its views of exquisite Forest Canyon and the bold heights of Trail Ridge.

Great is the temptation to linger on the inspiring ascent of Flattop, but one must not, for the journey is long. Flattop is well named. The eastern slopes of the Rockies are much gentler than the western precipices; for miles one may tramp on comparatively level rock, along the top of the Continental Divide. The top of Flattop Mountain, then, is a vast granite plateau strewn thickly with bowlders varying in size between a pumpkin and a cathedral. The trail wanders in and out among these rocks; it is marked, not by paths, but by cairns of loose rocks piled one on top of another. But to one who knows his general directions these are scarcely necessary, so open is the view.

Those who expect to find these bold mountain tops, 11,000 and 12,000 feet in altitude, devoid of life quickly find themselves greatly mistaken. Every altitude, everywhere in the world, has its own animal and vegetable life. Flattop, despite its height and seeming bareness, has its many and beautifully colored lichens, its many tiny mosslike grasses, its innumerable beautifully colored wild flowers. But these belong each to its own proper zone. Many species of arctic flowers of exquisite beauty are so small that they can only be found by attentive search.

A couple of miles south along this elevated snow-spattered crest, and "the Big Trail," as the Arapahoe Indians called it, plunges down the west side of the Rockies. The drop is into one of the impressive cirques at the head of the North Inlet. Sharp zigzags lead into dense forests through which the remarkable loveliness of the splendid granite walls are, unfortunately, seldom seen. The trail follows the river closely to Grand Lake.

To those who want to enjoy the supreme glories of the heart of the Rockies without crossing to the west side, the trip may be made as far as the summit of Flattop, where several hours may be spent in exploring the western front of the Continental Divide. It is an easy climb to the top of Hallett. South of Otis Peak, one may look down the Andrews Glacier into Loch Vale, a spectacle of real grandeur. And one may return the same day to his hotel in the eastern valley.

THE FALL RIVER TRAIL.

The other trail which crosses the Continental Divide is much longer. It passes westward up the Fall River Road as far as it is constructed and keeps straight on up and over the great wall of the Continental Divide.

The passage from dense forests to timberline and above it is here a matter of minutes. The ascent is inspiring, and the conquering of the Divide with the view beyond of the superlative valley of the Poudre River, of the magnificent sheep-haunted heights of Specimen Mountain, and of the beginning of the Forest Canyon, is highly dramatic.

THE TRAIL RIDGE TRAIL.

A variation of route to this point may be made by taking, from Moraine Park, the trail up Windy Gulch and along the top of Trail Ridge instead of through the Fall River Canyon. Both reach the same spot. But the Ute Trail, which was the Indian's route over the Continental Divide, whose altitude throughout is never less than 11,500 feet and at one place attains 12,227 feet, offers an experience not to be duplicated in any other national park. The entire crest of this remarkable ridge is scenic to a sensational degree. Windy Gulch is difficult, but well worth while.

But one may taste both experiences on the one trip at the expense of only 2 or 3 additional miles by going out by the Fall River Trail and, at the top of the Divide, swinging around the Forest Canyon cirque and coming back up Trail Ridge as far as Iceberg Lake. This gives the traveler practically the highest altitude and practically the best view which Trail Ridge affords. By either route, one must be sure to see Iceberg Lake.

ICEBERG LAKE.

This is a small abrupt cirque bitten for a depth of nearly a thousand feet into the eastern wall of the Trail Ridge. Its wall is almost precipitous. At its bottom lies a lakelet fed by a small glacier on which float ice cakes in August.

One can swing around its south side and descend to the water's edge. From every point of view it is admirable.

POUDRE LAKES AND MILNER PASS.

From the head of Forest Canyon the trail follows up the beautiful Poudre River, past the enormous volcanic pile of Specimen Mountain past two lakes of exquisite beauty, forest edged within a few hundred feet of timberline, and down by a precipitous zigzag which plunges nearly 2,000 feet to the valley of the North Fork of Grand River—whose waters, in due time, will flow through the Grand Canyon of the Colorado into the Gulf of California.

One may spend the night most comfortably at "Squeaky Bobs" excellent camp just outside the park boundary.

From this point south to Grand Lake, the traveler will follow an excellent road through a broad valley of wonderful beauty and variety, and return, if he chooses, by the Flattop Trail.

TRAILS TO LAWN LAKE.

The glories of the Mummy Range, exemplified chiefly in Lawn Lake and the Hallett Glacier, may be seen from a trail starting from Horseshoe Park by way of Roaring River. There is a camp on beautiful Lawn Lake. Lawn Lake has an altitude of 10,950 feet, and from its head Hagues Peak rises 2,600 feet higher.

The trip from the lake to the Hallett Glacier is difficult but well worth while. The glacier is not only one of the largest in the park; it is extraordinarily fine for its size, for any land. It is a great crescent of ice partly surrounding a small lake. While the glacier is extremely impressive, still it is small enough to permit a thorough examination without undue fatigue. Hagues Peak is a resort of Rocky Mountain sheep and ptarmigan.

THE WILD GARDENS.

The group of luxuriant canyons east of the Continental Divide and north of the eastern spur which ends in Longs Peak is known as the Wild Gardens in distinction from the corresponding and scarcely less magnificent hollow south of Longs Peak, which is known as the Wild Basin.

FERN AND ODESSA LAKES.

Of these canyons one of the most gorgeous frames two lakes of exquisite beauty. The upper one, Odessa Lake, lies under the Continental Divide and reflects snowy monsters in its still waters. The other, less than half a mile below, Fern Lake, is one of the loveliest examples of forest-bordered waters in the Rockies.

These lakes are reached by trail from Moraine Park. They constitute a day's trip of memorable charm. A primitive but most comfortable camp is located on Fern Lake. Stop over may be made at beautiful Forest Inn, at the Pool.

BEAR LAKE.

Lying directly under Hallett Peak, whose broken granite shaft is seen reflected in its forest-bordered waters, lies Bear Lake, noted for its wildness and its excellent fishing. It can be reached by trail both from Moraine and Bartholf Parks. There is an excellent camp on its west shore, with plenty of boats.

ROMANTIC LOCH VALE.

Within a right-angled bend of the Continental Divide lies a glacier-watered, cliff-cradled valley which for sheer rocky wildness and the glory of its flowers has few equals. At its head Taylors Peak lifts itself precipitously 3,000 feet to a total height of more than 13,000, and from its western foot rises Otis Peak, of nearly equal loftiness, the two carrying between them broken perpendicular walls carved by the ages into fantastic shape. One dent incloses Andrews Glacier and lets its water find the loch. On the eastern side another giant, Thatchtop, sheltering the Taylor Glacier from the north, walls all in. It is easily reached by trail from Sprague's.

In this wild embrace lies a valley 2 or 3 miles long ascending from the richest of forests to the barren glacier. Through it tinkles Icy Brook, stringing, like jewels, three small lakes. Of these the lowest is inclosed by a luxuriant piny thicket. The two others, just emerging over timberline, lie set in solid rock sprinkled with snow patches, Indian paintbrush, and columbines.

This valley is called Loch Vale. It is only 8 or 9 miles by mountain road and trail from the well-populated hotels in Moraine Park, but it is little visited because the road is poor and the trail primitive.

Those who make the journey seldom go farther than the nearest shore of the outlet lake, the loch, because beyond that is a tangled wilderness and there is no trail into the rock-bound vale above. A few visit the foot of the little Andrews Glacier in the western valley, but no more than a dozen worshipful nature lovers a year make their way up the gorgeous gardens of the main valley, over the Timberline Fall, to look into the Lake of Glass, to trace the convolutions of those tessellated rock rims against the blue above, and to see the clouds reflected in Sky Pond.

This valley, which, with Glacier Gorge adjoining, is called the Wild Gardens in distinction from the corresponding mountain angle south of Longs Peak which Enos Mills named the Wild Basin, makes a deep impression upon the beauty-loving explorer. The loch at its entrance, shut in by forest, overhung by snow-patched mountain giants and enlivened by the waterfall pouring from a high, rocky shelf up the vale, makes a first impression never to be forgotten. Here, under trees on a tiny promontory, is the spot for lunch.

But the floor of the valley as, going forward, you emerge from timberline is the gorgeous feature of the vale, competing successfully even with the fretted and towering rocks. Such carpeting triumphantly defies art. Below the falls the brook divides and subdivides into many wandering streamlets, often hidden wholly in the luxuriant masses of flowering growths of many kinds and of infinite variety of color. One must step carefully to avoid an icy foot bath, for there is no trail. Low piny growths, dwarfed spruce, and alpine birches group in picturesque clumps. You pass from glade to glade, discovering new and unexpected beauty every few rods. Your highest ambition is to raise a tent back among those small spruces and live here all alone with this luxuriance.

The scramble up the rocky shelf that holds the falls is stiff enough to scrape your hands and steal your breath, and here you find another world. The same grand sculptures surround you, but your carpet is changed to tumbled rock—rock that carries in innumerable hollows patches alternately of snow and floral glory.

Here grow in late August columbines of size and hue to shame the loveliest of New England's springtime. For in these altitudes August is the Eastern May. Here, all summer blooms at once. Indian paintbrush shades from its most gorgeous red through all degrees to faint green. Asters, from lavender to deepest purple, group themselves alongside snow banks. Alpine flowerlets never seen below the highest levels peep from the mosses between the rocks. Here, just over the edge of the rock shelf, lies a lake so clear that every pebble on its bottom shows in relief. It is truly the Lake of Glass.

Passing on, the vale still rises and at its head, in the very hollow of the precipices, hemmed in by snow and watered from the glacier, lies the gem of all, Sky Pond. From the bowlders on the eastern side you draw a long breath of pleasure, for, looking backward, you see far down the vale over the rim of the falls the exquisite distant loch shining among its spruces.

All that lacks is life and motion. But here are these, too, in the insects that hum about you. And presently a chipmunk scampers over a bowlder. A sharp whistle draws the eye across the pond to a dark spot by a snow bank on the water's edge. It is a woodchuck calling his wife to come out and enjoy the sunshine. She answers, he replies, and presently the two wander away together and are lost among the rocks.

GLACIER GORGE.

One of the noblest gorges in any mountain range the world over lies next south of Loch Vale. It is reached from Sprague's by the Loch Vale trail. Its western walls are McHenrys Peak and Thatchtop; its head lies in the hollow between the Continental Divide and Longs Peak, with Chiefs Head and Pagoda looming on its horizon, and its eastern wall is the long sharp northern buttress of Longs Peak itself.

It is a gorge of indescribable wildness. Black Lake and Blue Lake are the only two of half dozen in its recesses which bear names. Lake Mills lies in its jaws.

This gorge is magnificently worth visiting. It may be done in a day from Sprague's, returning for dinner. There is no trail to Keyhole on the great shoulder of Longs Peak, but the ascent may be made readily. The canyon is luxuriantly covered in places with a large variety of wild flowers.

THE TWIN SISTERS.

Nine miles south of the village of Estes Park, split by the boundary line of the national park, rises the precipitous, picturesque, and very craggy mountain called the Twin Sisters. Its elevation is 2,300 feet above the valley floor, which there exceeds 9,000 feet. The trail leads by many zigzags to a peak from which appears the finest view by far of Longs Peak and its guardians, Mount Meeker and Mount Lady Washington.

From the summit of the Twin Sisters an impressive view is also had of the foothills east of the park, with glimpses beyond of the great plains of eastern Colorado, and many of their irrigating reservoirs.

THE ASCENT OF LONGS PEAK.

Of the many fascinating and delightful mountain climbs, the ascent of Longs Peak is the most inspiring, as it is the most strenuous. The great altitude of the mountain, 14,255 feet above sea level and more than 5,000 feet above the valley floor, and its position well east of the Continental Divide, affording a magnificent view back upon the range, make it much the most spectacular viewpoint in the park. The difficulty of the ascent also has its attractiveness. Longs Peak is the big climb of the Rocky Mountain National Park.

And yet the ascent is by no means forbidding. One may go more than halfway by horseback. Several hundred men and women, and occasionally children, climb the peak each season.

The three starting places are Hewes-Kirkwood Ranch, the Columbines Hotel, and Longs Peak Inn, 9 miles south of Estes Park, but those who want to have plenty of time to see and enjoy prefer to spend the night at Timberline Cabin on the shoulder between Longs Peak and Mount Lady Washington; from here the trail winds through Boulder Field, an area of loose rocks on the north of the peak. From Boulder Field, the trail ascends by a devious, sometimes exciting course, through a hole in a rocky wall called, from its shape, the Keyhole, and up sharp rocky slants often covered with ice and snow.

Passing through Keyhole, the imposing vista of the Front Range bursts upon the view. We look 2,000 feet down into Glacier Gorge. To the left we pass up a narrow, steeply inclined ice-filled gulch, called the Trough; this is the only part of the climb which can be called dangerous, and it is not always dangerous. Finally, after what is to the amateur often an exhausting climb, we pass along the Narrows, up a steep incline called the Homestretch, and we are there.

The view from Longs Peak in most directions is nothing less than sublime.

SUNRISE FROM LONGS PEAK.

A night ascent of Longs Peak is necessary to see the wonderful spectacle of sunrise from the summit. Here is the story of an ascent made in August, 1915, by Miss Edna Smith, Mrs. Love, Miss Frasher, and Miss Terry, under the guidance of Shep Husted. The account is by Miss Smith.

At supper time the chances seemed against a start. It was raining. Later the rain stopped but the full moon was almost lost in a heavy mist and the light was dim. Mr. Husted thought an attempt to ascend the peak hardly wise. At 11 o'clock I went to Enos Mills for advice. He said, "Go." So we mounted Our ponies and started, chilled by the clammy fog about us.

After a short climb we were in another world. The fog was a sea of silvery clouds below us and from it the mountains rose like islands. The moon and stars were bright in the heavens. There was the sparkle in the air that suggests enchanted lands and fairies. Halfway to timberline we came upon ground white with snow, which made it seem all the more likely that Christmas Pixies just within the shadows of the pines might dunce forth on a moon beam.

Above timberline there was no snow, but the moonlight was so brilliant that the clouds far below were shining like misty lakes and even the bare mountain side about us looked almost as white as if snow covered.

As we left our ponies at the edge of the Boulder Field and started across that rugged stretch of débris spread out flat in the brilliant moonlight we found the silhouette of Longs Peak thrown in deep black shadow across it. Never before had that bold outline seemed so impressive.

At the western edge of Boulder Field there was a new marvel. As we approached Keyhole, right in the center of that curious nick in the rim of Boulder Field shone the great golden moon. The vast shadow of the peak, made doubly dark by the contrast, made us very silent. When we emerged from Keyhole and looked down into the Glacier Gorge beyond it was hard to breathe because of the wonder of it all. The moon was shining down into the great gorge 1,000 feet below and it was filled with a silvery glow. The lakes glimmered in the moonlight.

Climbing along the narrow ledge, high above this tremendous gorge, was like a dream. Not a breath of air stirred, and the only sound was the crunch of hobnails on rock. There was a supreme hush in the air, as if something tremendous were about to happen.

Suddenly the sky, which had been the far-off blue of a moonlit night, flushed with the softest amethyst and rose, and the stars loomed large and intimately near, burning like lamps with lavender, emerald, sapphire, and topaz lights. The moon had set and the stars were supreme.

The Trough was full of ice and the ice was hard and slippery, but the steps that had been cut in the ice were sharp and firm. We had no great difficulty in climbing the steep ascent, We emerged from the Trough upon a ledge from which the view across plains and mountain ranges was seemingly limitless.

As we made our way along the Narrows the drama of that day's dawn proceeded with kaleidoscopic speed. Over the plains, apparently without end, was a sea of billowy clouds, shimmering with golden and pearly lights. One mountain range after another was revealed and brought close by the rosy glow that now filled all the sky. Every peak, far and near, bore a fresh crown of new snow, and each stood out distinct and individual. Arapaho Peak held the eye long. Torreys Peak and Grays Peak were especially beautiful. And far away, a hundred miles to the south, loomed up the summit of Pikes Peak. So all-pervading was the alpine glow that even the near-by rocks took on wonderful color and brilliance.

Such a scene could last but a short time. And it was well for us, for the moments were too crowded with sensations to be long borne. Soon the sun burst up from the ocean of clouds below. The lights changed. The ranges gradually faded into a far-away blue. The peaks flattened out and lost themselves in the distance. The near-by rocks took on once more their accustomed somber hues. And in the bright sunlight of the new day we wondered whether we had seen a reality or a vision.

On the summit all was bright and warm. Long we lingered in the sunlight, loath to leave so much beauty; but we feared lest the ice in the Trough should soften, and at last we began the descent. We descended leisurely and stopped at Timberline Cabin for luncheon.

It was a perfect trip. It seemed as if the stage were set for our especial benefit. It was an experience that will live with me always. At first I felt as if I could never ascend the peak again, lest the impressions of that perfect night should become confused or weakened. But I believe I can set this night apart by itself. And I shall climb Longs Peak again.

THE ASCENT IN THE SNOW.

But Longs Peak does not always present the same gentle aspects. In September of the same year Mr. D. W. Roper, of Chicago, made the ascent, contrary to the advice of those who knew its perils, immediately following a snowstorm which had kept him waiting for several days. Describing his experiences he said:

After leaving the Keyhole the general direction of the trail was indicated by a few cairns, but they were very scarce. The footprints in the snow of a party that had made the ascent the previous day were of considerable assistance and particularly so in the Trough, where I found their steps cut in the ice and crusty snow. I did not have to cut more than six or eight steps, and as I had nothing that could be used for the purpose except my hunting knife this was very fortunate.

The ascent from the Keyhole to the summit required an hour and thirty minutes. In the Trough I was on all fours about half the time and did considerable climbing over and amongst the bowlders. I would characterize the ascent as dangerous rather than difficult. There was no snow of any consequence except in the Trough, although the notes in the register on the summit showed that the party had found 2 inches on the summit the previous day.

I had taken opportunity to enjoy the many magnificent views on the way up the peak, and it was fortunate that I did so, as I there found a storm gathering, the clouds being about on the level with the summit of the peak and snow starting to fall. I made a slight tour of the summit and then located and examined the register of the Colorado Mountain Club.

The snowfall rapidly increased, so that in 20 minutes after reaching the summit I started the descent, as I feared difficulty due to the snow covering the steps in the ice through the Trough. My fears were well founded. More than half of the steps were not only filled but entirely covered and obliterated, so that it was inmpossible to locate them. There were several places from 50 to 100 feet wide or more between the bowlders along the side of the Trough where there was no sign of any footing, and if one should start to slip it was hard to see just where one might expect to stop. The only certain place appeared to be down near Glacier Lake, some 2,000 feet below.

In these places I made steps by repeated kicks with my heel, at the same time making handholds higher up with my hands in the crusty snow.

Fortunately, I was able to find the steps in that portion of the side of the Trough that was covered with ice. In one place I attempted to go down over a bowlder by lowering myself feet first, but after getting so far that I swung freely below the chest I found it impossible to find safe footing and had to climb up again over the bowlder. As this bowlder was located in a position with a steep crusty snow slope below it, the climbing up was attended with some danger, and especially so as the first part of the climbing consisted of a series of kicks and wriggles in an attempt to lift my clothing clear of the rough bowlder and to move forward at the same time until I could bring my foot or knee into action.

The trail was very dim after getting out of the Trough. Several times I found myself a considerable distance above the trail, and nearly descended through the transom, if there is one, instead of the Keyhole. The difficulties in the Trough and in losing the trail resulted in my making the descent to the Keyhole in 1 hour and 35 minutes, or five minutes longer than the time required for the ascent.

THE WILD BASIN.

This splendid area south of Longs Peak and east of the Continental Divide is the land of the future. Its mountain surroundings have sublimity. It is dotted with lakes of superb beauty. It is fitted to become the camping ground of large summer throngs.

It is entered from Copeland Lake by a poor road up the North Fork of St. Vrain Creek which soon lapses into a rude trail. From mountain tops on the south of this superb basin may be had views which are unsurpassed of the snowy mountains.

No one enters the Wild Basin without exclaiming over the startling beauty of the St. Vrain Glaciers which lie on the crest of the Continental Divide toward the south. They, together with many other scenic features of sensational character, lie outside the park boundary.

FROM THE WEST SIDE.

From Grand Lake the Rocky Mountain National Park presents an aspect so different as not to seem the same neighborhood. The gentler slopes leading up to the Continental Divide from this side produce a type of beauty superlative of its kind though less startling in character. The country is charming in the extreme. The valley of the Grand River, from whose western shores rise again the Continental Divide, now bent around from the north and here called the Medicine Bow Mountains, is magnificently scenic. The river itself winds wormlike within a broad valley.

From the river westward the park slopes are heavily forested. The mountains, picturesquely grouped, lift bald heads upon every side. Splendid streams rush to the river. Magnificent canyons penetrate to the precipices of the divide. Many lakes of great beauty cluster under the morning shadows of these great masses.

GRAND LAKE.

The North and East Inlets are the two principal rivers entering beautiful Grand Lake. Each flows from cirques under the Continental Divide. Lake Nokoni and Lake Nanita, reputed among the most romantic of the park, are reached by a new trail connecting with both sides of the park by the Flattop Trail.

Lake Verna and her unnamed sisters are the beautiful sources of the East Inlet and are reached by its trail.

While not yet so celebrated as the showier and more populated east side, the west side of the Rocky Mountain National Park is destined to an immense development in the not far future. With the completion of the Fall River road in 1920 the west side will begin to come into its own.

CAMPING OUT.

The facilities for comfortable summer living afforded by the great plateau with its parklike valleys which lies east of the snowy range are, equally with the park's accessibility to centers of large population, the reasons for its enormous recent increase in popularity. It is destined to become a famous center for camping out.

To this end, a public camp ground was established in Bartholf Park. In this camp ground motorists and others who bring in tents and camping-out equipment will find comfortable spots in which to enjoy themselves in the way which many believe the ideal one to live in the open.

THE SNOW CARNIVAL.

So accessible a winter paradise inevitably suggests winter sports, and winter sports there are. There is no country more adaptable to the purpose. With some hotels open the year around, snowshoe trips are possible everywhere, also tobogganing and skiing.

For the formal snow carnival in February, Fern Lake has been appropriately chosen. The neighborhood is one of the wildest and most beautiful in the Rockies. The Fern Lake Lodge makes a picturesque headquarters. The snow-covered surface of the lake, girt close with lofty Englemann spruce and framed in summits of the Continental Divide, is an inspiring field. Here, from February's beginning, skiing and other lusty sports draw an increasing number of devotees of winter pleasure.

THE MOUNTAIN PEAKS.

Front Range peaks following the line of the Continental Divide, north to south.

| A little west of the divide. | On the Continental Divide. | A little east of the divide. | Altitude, in feet. |

| Specimen Mountain | 12,482 | ||

| Shipler Mountain | 11,400 | ||

| Mount Ida | 12,725 | ||

| Terra Tomah Peak | 12,686 | ||

| Mount Julian | 12,928 | ||

| Stones Peak | 12,928 | ||

| Flattop Mountain | 12,300 | ||

| Hallett Peak | 12,725 | ||

| Otis Peak | 12,478 | ||

| Taylor Peak | 13,150 | ||

| Thatchtop | 12,600 | ||

| McHenrys Peak | 13,200 | ||

| Storm Peak | 13,335 | ||

| Chiefs Head | 13,579 | ||

| Pagoda | 13,491 | ||

| Longs Peak | 14,255 | ||

| Mount Lady Washington | 13,269 | ||

| Mount Meeker | 13,911 | ||

| Mount Alice | 13,310 | ||

| Andrews Peak | 12,564 | ||

| Tanina Peak | 12,417 | ||

| Mount Craig | 12,005 | ||

| Mahana Peak | 12,629 | ||

| Ouzel Peak | 12,600 | ||

| Mount Adams | 12,115 | ||

| Mount Copeland | 13,176 | ||

| Estes Cone | 11,017 | ||

| Battle Mountain | 11,930 | ||

| Lookout | 10,744 | ||

| Mount Orton | 11,682 | ||

| Meadow Mountain | 11,634 | ||

Peaks of the Mummy Range northeast of the Continental Divide from Fall River, north.

| Altitude, in feet. | |

| Mount Chapin | 12,458 |

| Mount Chiquita | 13,052 |

| Ypsilon Mountain | 13,507 |

| Mount Fairchild | 13,502 |

| Mummy Mountain | 13,413 |

| Hagues Peak | 13,562 |

| Mount Dunraven | 12,548 |

| Mount Dickinson | 11,874 |

| Mount Tileson | 11,244 |

| Big Horn Mountain | 11,473 |

| McGregor Mountain | 10,482 |

Peaks in the Grand Lake Basin.

| Snowdrift Peak | 12,280 |

| Nakai Peak | 12,221 |

| Mount Patterson | 11,400 |

| Mount Bryant | 11,000 |

| Mount Cairns | 10,800 |

| Nisa Mountain | 10,791 |

| Mount Enentah | 10,737 |

| Mount Wescott | 10,400 |

| Shadow Mountain | 10,100 |

The above tables show that there are 51 named mountains within the very limited area of the park that reach attitudes of over 10,000 feet, grouped as follows:

| Over 14,000 feet | 1 |

| Between 13,000 and 14,000 feet | 13 |

| Between 12,000 and 13,000 feet | 20 |

| Between 11,000 and 12,000 feet | 10 |

| Between 10,000 and 11,000 feet | 7 |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

1920/romo/sec4.htm

Last Updated: 16-Feb-2010