|

GLACIER

Rules and Regulations 1920 |

|

GLACIER NATIONAL PARK.

GENERAL DESCRIPTION.

The Glacier National Park, in northwestern Montana, incloses 981,681 acres or 1,534 square miles of the noblest mountain country in America. The park was established by the act of May 11, 1910. Its name is derived from its 60 glaciers. There are more than 90 all told, if one classes as glaciers many interesting snow patches of only a few acres each, which exhibit most of the characteristics of true glaciers. It possesses individuality in high degree. In ruggedness and sheer grandeur it probably surpasses the Alps, though geologically it is markedly different. It resembles the Canadian Rockies more closely than any other scenic country. The general geological structure is the same in both, but the rocks of Glacier are enormously older and much more richly colored. The Canadian Rockies have the advantage of more imposing masses of snow and ice in summer, but, for that very reason, Glacier is much more easily and comfortably traveled.

Glacier strongly differentiates also from other mountain scenery in America. Ice-clad Rainier, mysterious Crater Lake, spouting Yellowstone, exquisite Yosemite, beautiful Sequoia—to each of these and to all others of our national parks Glacier offers a highly individualized contrast.

Nor is this scenic wonderland merely a sample of the neighborhood. North of the park the mountains rapidly lose their scenic interest. South and west there is little of greater interest than the mountains commonly crossed in a transcontinental journey. To the east lie the Plains.

To define Glacier National Park, picture to yourself two approaching chains of vast tumbled mountains, the Livingston and Lewis Ranges, which pass the Continental Divide back and forth between them in wormlike twistings, which bear living glaciers in every hollow of their loftiest convolutions, and which break precipitately thousands of feet to lower mountain masses, which, in their turn, bear innumerable lakes of unbelievable charm, offspring of the glaciers above; these lakes, in their turn, giving birth to roaring rivers of icy water, leaping turbulently from level to level, carving innumerable sculptured gorges of grandeur and indescribable beauty.

These parallel mountain masses form a central backbone for the national park. Their western sides slope from the summit less precipitately. Their eastern sides break abruptly. It is on the east that their scenic quality becomes titanic.

A ROMANCE IN ROCKS.

To really comprehend the personality of Glacier, one must glance back for a moment into the geological past when the sea rolled over what is now the northwest of this continent. If you were in the Glacier National Park to-day, you would see broad horizontal bands of variously colored rocks in the mountain masses thousands of feet above your head. These are the very strata that the waters deposited in their depths centuries of centuries ago.

|

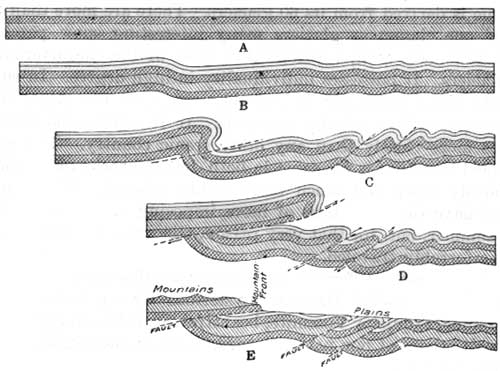

| DIAGRAM 1.—How internal pressure transformed level rock into the tumbled masses of the Glacier National Park. The Lewis Overthrust. |

According to one famous theory of creation, the earth has been contracting ever since a period when it was once gas. According to Chamberlain's recent theory, it never was a globe of gas, but a mass of rocks which continually shift and settle under the whirling motion around its axis. Whichever theory you accept, the fact stands that, as it contracted, its sides have bulged in places like the sides of a squeezed orange. This is what must have happened where the Glacier National Park now is. Under urge of the terrible squeezing forces the crust lifted, emerged, and became land. Untold ages passed, and the land hardened into rock. And all the time the forces kept pressing together and upward the rocky crust of the earth.

For untold ages this crust held safe, but at last pressure won. The rocks first yielded upward in long, irregular, wavelike folds. Gradually these folds grew in size. When the rocks could stand the strain no longer, great cracks appeared, and one broken edge, the western, was thrust upward and over the other. The edge that was thrust over the other was thousands of feet thick. Its crumbling formed the mountains and the precipices.

When it settled, the western edge of this break overlapped the eastern edge 10 to 15 miles. A glance at diagram 1 will make it clear. A represents the original water-laid rock; B the first yieldings to internal pressure; C the great folds before the break came; D and E the way the western edges overlapped the eastern edges when the movement ceased.

THE LEWIS OVERTHRUST.

This thrusting of one edge of the burst and split continent over the other edge is called faulting by geologists, and this particular fault is called the Lewis Overthrust. It is the overthrust which gives the peculiar character to this amazing country, that and the inconceivably tumbled character of the vast rocky masses lying crumbling on its edges.

It is interesting to trace the course of the Lewis Overthrust on a topographic map of the park. The Continental Divide, which represents the loftiest crest of this overthrust mass, is shown on the map. These two irregular lines tell the story; but not all the story, for the snow and the ice and the rushing waters have been wonderfully and fantastically carving these rocks with icy chisels during the untold ages since the great upheaval.

MAGNIFICENTLY COLORED STRATA.

To understand the magnificent rocky coloring of Glacier National Park, one must go back a moment to the beginning of things. The vast interior of the earth, more or less solid rock according to Chamberlain, is unknown to us because we have never been able to penetrate farther than a few thousand feet from the surface. The rock we do not know about, geologists call the Archean. What we do know a good deal about are the rocks above the Archean. Of these known rocks the very lowest and consequently the oldest are the rock strata which are exposed in Glacier National Park. Geologists call these strata the Algonkian. They were laid as an ocean bottom sediment at least 80,000,000 years ago. Some of the rocks of this age appear in the Grand Canyon of the Colorado, but nowhere in the world are they displayed in such area, profusion, and variety and magnificence of coloring as in Glacier National Park.

|

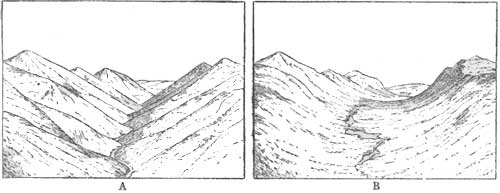

| DIAGRAM 2.—Showing form of a stream-cut valley (A) and of the same valley (B) after it has been occupied by a glacier. |

These Algonkian rocks lie in four differently colored strata, all of which the visitor at Glacier may easily distinguish for himself. The lowest of these, the rock that actually lay next to the old Archean, is called the Altyn limestone. This is about 1,600 feet thick. It is faint blue inside, but it weathers a pale buff. There are whole yellow mountains of this on the eastern edge of the park.

Next above the Altyn limestone lies a layer of Appekunny argillite, or green shale. This is about 3,400 feet thick. It weathers every possible shade of dull green.

Next above that lies more than 2,200 feet of Grinnell argillite, or red shale. This weathers every possible shade of deep red and purple, almost to black. Both the shales have a good deal of white quartzite mixed with them.

Next above that rises more than 4,000 feet of Siyeh limestone, very solid, very massive, very gray, and running in places to yellow. Horizontally through the middle of this is seen a broad dark ribbon or band; one of the characteristic spectacles in all parts of Glacier National Park. This is called the diorite intrusion. It is as hard as granite. In fact it is very much like granite, indeed. It got there by bursting up from below when it was fluid hot and spreading a layer all over what was then the bottom of the sea. When this cooled and hardened more limestone was deposited on top of it, which is why it now looks like a horizontal ribbon running through those lofty gray limestone precipices.

In some parts of the park near the north there are remnants of other strata which surmounted the Siyeh limestone, but they are so infrequent that they interest only the geologists. The four strata mentioned above are, however, plain to every eye.

Now, when these vividly colored rocks were lifted high in the air from their first resting place in the sea bottom, and then cracked and one edge thrust violently over the other, they sagged in the middle just where the park now lies. If a horizontal line, for instance, were drawn straight across Glacier National Park from east to west it would pass through the bottom of the Altyn limestone on the east and west boundaries; but in the middle of the park it would pass through the top of the Siyeh limestone. Therefore it would, and does, cut diagonally through the green and the red argillites on both sides of the Continental Divide. That is why all this colorful glacier country appears to be so upset, twisted, inextricably mixed. Bear in mind this fact and you will soon see reason and order in what to the untutored eye seems a disorderly kaleidoscope.

Thus was formed in the dim days before man, for the pleasure of the American people of to-day, the Glacier National Park.

CARVED BY WATER AND ICE.

It probably took millions of years for the west edge of the cracked surface to rise up and push over the east edge. When this took place is, geologically speaking, quite clear, because the ancient Algonkian rock at this point rests on top of rocks which have been identified by their fossils as belonging to the much younger Cretaceous period. How much younger can not be expressed in years or millions of years, for no man knows. It is enough to say here that the whole process of overthrusting was so slow that the eroding of all the strata since which lay above the Algonkian may have kept almost abreast of it.

Anyway, after the fault was fully accomplished, the enormously thick later strata all washed away and the aged Algonkian rocks wholly exposed, it took perhaps several million years more to cut into and carve them as they are cut and carved to-day.

This was done, first, by countless centuries of rainfall and frost; second, by the first of three ice packs which descended from the north; third, by many more centuries of rainfall, frost, and glacier; fourth, by the second ice pack; fifth, by many more centuries of rainfall, frost, and glacier; sixth, by the third ice pack; and seventh, by all the rains and frosts down to the present time, the tiny glaciers still remaining doing each its bit.

The result of all this is that in entering Glacier National Park to-day the visitor enters a land of enormous hollowed cirques separated from each other by knife-edged walls, many of which are nearly perpendicular. Many a monster peak is merely the rock remains of glacial corrodings from every side, supplemented by the chipping of the frosts of winter and the washing of the rains and the torrents.

Once upon the crest of the Continental Divide, one can often walk for miles along a narrow edge with series of tremendous gulfs on both sides. Where glaciers have eaten into opposite sides of the Continental Divide so far that they have begun to cut down the dividing wall, passes are formed; that is, hollows in the mountain wall which permit of readier passage from side to side. Gunsight Pass is of this kind. So are Dawson, Swiftcurrent, Triple Divide, Red Eagle, Ptarmigan, Piegan, and many others.

Any visitor to Glacier National Park can identify these structural features with ease, and a knowledge of them will greatly increase his pleasure in the unique scenery. Even the casual visitor may identify the general features from the porches of the hotels and chalets, while a hiking or horseback trip from the Many Glacier Hotel to Iceberg Lake, over Swiftcurrent Pass to Granite Park, over Piegan Pass to St. Mary Lake, or over Piegan and Gunsight Passes to Lake McDonald, will serve to fix the glacier geological conformation in mind so definitely that the experience will always remain one of the happiest and most enlightening in one's life.

|

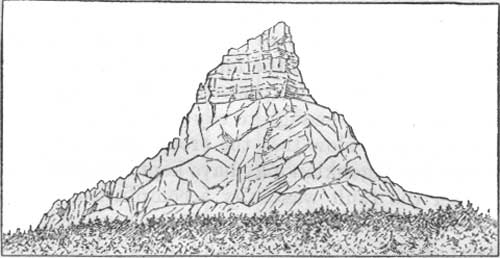

| DIAGRAM 3.—Diagram showing structure of Chief Mountain. Limestone in upper part not disturbed, but that in lower part duplicated by many minor oblique thrust faults. After Bailey Willis. |

ADVANTAGES OF CAMPING OUT.

It is to the more leisurely traveler, however, that comes the greater joy. He who travels from hotel to chalets, from chalets to hotel, and then, having seen the things usually seen, engages a really competent guide, takes horses and camping outfit, and embarks upon the trails to wander and to linger where he will, is apt to find a month or more in Glacier National Park an experience wonderfully rich in knowledge and in pleasure.

Notwithstanding the excellent equipment of the Saddle Horse Co., such an experience is not unadventurous. Once off the excellent trails in the developed part of the park, the trails are little better than the original game trails. Unimproved wilderness is as rough in Glacier National Park as anywhere else. But compensations are many. Wild animals are more frequent and tamer, fishing is finer, and there is the joy, by no means to be despised, of feeling oneself far removed from human neighborhood. On such trips one may venture far afield, may explore glaciers, may climb divides for extraordinary views, may linger for the best fishing, may spend idle days in spots of inspirational beauty.

The Saddle Horse Co., provides excellent small sleeping tents and a complete outfitting of comforts. But insist on two necessities—a really efficient guide and a Government contour map. Learn to read the map yourself, consult it continually, and Glacier is yours.

This advice about the map applies to all visitors to Glacier who at all want to understand. To make sure, get your Government map yourself. It can be had for 25 cents from the park superintendent at Belton, Mont., or by mail at the same price from the United States Geological Survey, Washington, D. C.

A GENERAL VIEW.

From the Continental Divide, which, roughly speaking, lies north and south through the park, descend 19 principal valleys, 7 on the east side and 12 on the west. Of course, there are very many smaller valleys tributary to each of these larger valleys. Through these valleys run the rivers from the glaciers far up on the mountains.

Many of these valleys have not yet been thoroughly explored. It is probable that some of them have never yet been even entered unless possibly by Indians, for the great Blackfeet Indian Reservation, one of the many tracts of land set apart for the Indians still remaining in this country, adjoins the Glacier National Park on the east.

There are 250 known lakes. Probably there are small ones in the wilder parts which white men have not yet even seen.

The average tourist really sees a very small part of the glorious beauties of the region, though what he does see is eminently typical. He usually enters at the east entrance, visits the Two Medicine Lakes, and passes on to St. Mary Lake, believed by many travelers the most beautiful lake in the world. After seeing some of the many charms of this region, he passes on to Lake McDermott, in the Swiftcurrent Valley. The visitor then usually crosses over the famous Gunsight Pass to the west side, where he usually but foolishly contents himself with a visit to beautiful Lake McDonald and leaves by the Belton entrance.

THE WEST SIDE.

But the west side contains enormous areas which some day will be considered perhaps the finest scenery in the accessible world. To the north of Lake McDonald lie valleys of unsurpassed grandeur. At the present time they may be seen only by those who carry camp outfits with them.

Bowman Lake and its valley, Kintla Lake and its valley—these are names which some day will be familiar on both sides of the sea.

HISTORY.

This region appears not to have been visited by white men before 1853, when A. W. Tinkham, a Government engineer, exploring a route for a Pacific railroad, ascended Nyack Creek by mistake and retraced his steps when he discovered the impracticability for railroad purposes of the country he had penetrated.

The next explorers were a group of surveyors establishing the Canadian boundary line. This was in 1861. In 1890 copper ore was found at the head of Quartz Creek and there was a rush of prospectors. The east side of the Continental Divide, being part of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, was closed to prospectors, and Congress was importuned for relief. In 1896 this was purchased from the Indians for $1,500,000, but not enough copper was found to pay for the mining. Thereafter it was visited only by big game hunters and occasional lovers of scenery. It was made a national park May 11, 1910.

EAST SIDE VALLEYS.

Glacier National Park is best studied valley by valley. There are 7 principal valleys on its eastern side, 12 on its west. Let us consider its eastern side first, beginning at the south as you enter from the railroad entrance at Glacier Park Station.

TWO MEDICINE VALLEY.

Because of its location, Two Medicine Valley is one of the best known sections of Glacier. It is a capital illustration of the characteristic effects of glacial action on valleys as shown by diagram 2. The automobile stage skirts the eastern side of the range for half an hour, and turning west past Lower Two Medicine Lake, penetrates the range south of noble Rising Wolf Mountain. The road stops at the chalets at the foot of Two Medicine Lake, fronting a group of highly colored, ornately carved mountains, which has become one of the country's celebrated spectacles. Back of triangular Mount Rockwell across the water is seen the Continental Divide.

Most tourists content themselves with a visit of two or three hours, including luncheon at the chalets. But the few who take horse and explore the noble cirque system west of the lake, and, climbing the divide, look over Dawson Pass upon the tumbled snow-daubed peaks of the lower west side, have an unforgetable experience. Another trail route leads from the chalets up Dry Fork to Cut Bank Pass, from the top of which one trail leads into the west side valley of Nyack Creek, disclosing the same view as that from Dawson Pass, but at a different angle, and another trail drops into the noble lake-studded cirque which is the head of North Fork of Cut Bank Creek. There are few finer spots in America than the top of Cut Bank Pass, with its indescribable triple outlook.

CUT BANK VALLEY.

Cut Bank Valley, next to the north, is another glacier-rounded valley. It is one of the easiest to explore. It is entered by trail from the south, as described above, or by automobile from east of the park boundary; the road ends at the Cut Bank Chalets, picturesquely situated on North Fork of Cut Bank Creek at the foot of Amphitheater Mountain. Cut Bank Valley has also a northern cirque at the head of which is one of the most interesting passes in the Rocky Mountains. From Triple Divide Peak the waters flow in three directions, to the Gulf of Mexico by Cut Bank Creek and the Missouri River, to Hudson Bay by St. Mary River, and to the Pacific Ocean by Flathead River. Triple Divide Pass crosses a spur which connects Mount James with the Continental Divide, but it does not cross the divide itself. The Pass leads down into Norris Creek Basin and thence into Red Eagle Valley. Cut Bank Chalets afford excellent accommodations. Large trout are abundant in the neighborhood.

RED EAGLE VALLEY.

Red Eagle Valley, still farther north, is one of the most picturesque in the park. Its glacier was once 2,000 feet deep. One of its several existing glaciers may be seen from any point in the valley. This important valley originates in two principal cirque systems. The lesser is the Norris Creek Basin, above referred to. The greater is at the head of Red Eagle Creek, a magnificent area lying almost as high as the Continental Divide and carrying the picturesque Red Eagle Glacier and a number of small unnamed lakes. Mount Logan guards this cirque on the west, Almost-a-Dog Mountain on the north. The valley from this point to the mouth of Red Eagle Creek in St. Mary Lake near the park boundary is very beautiful, broad, magnificently forested and bounded on the north by the backs of the mountains whose superb front elevations make St. Mary Lake famous. Red Eagle Lake is celebrated for its large cutthroat trout.

ST. MARY VALLEY.

St. Mary Valley, the next to the north, is one of the largest and most celebrated. Its trail to Gunsight Pass is the principal highway across the mountains to the western slopes. It is one of the loveliest of lakes, surrounded by many imposing mountain peaks, among them Red Eagle Mountain, whose painted argillites glow deeply; Little Chief Mountain, one of the noblest personalities in Glacier; Citadel Mountain, whose eastern spur suggests an inverted keel boat; Fusilade Mountain, which stands like a sharp tilted cone at the head of the lake; Reynolds Mountain, which rises above the rugged snow-flecked front of the Continental Divide; and, on the north, Going-to-the-Sun Mountain, one of the finest mountain masses in any land. The view west from the Going-to-the-Sun Chalets is one of the greatest in America.

SWIFTCURRENT VALLEY.

Swiftcurrent Valley, next to the north, was famous in the mining days and is famous to-day for the sublimity of its scenery. It is by far the most celebrated valley in the parks so far, and will not diminish in popularity and importance when the more sensational valleys in the north become accessible. Its large and complicated cirque system centers in one of the wildest and most beautiful bodies of water in the world, Lake McDermott, upon whose shores stand the Many Glacier Hotel and the Many Glacier Chalets. No less than four glaciers are visible from the lake shore and many noble mountains. Mount Grinnell, the monster of the lake view, is one of the most imposing in the park, but Mount Gould, up the Cataract Creek Valley, vies with it in magnificence and, as seen from the lake, excels it in individuality. The view westward up the Swiftcurrent River is no less remarkable, disclosing Swiftcurrent Peak, the Garden Wall in its most picturesque aspects, and jagged Mount Wilbur, inclosing the famous Iceberg Gorge. From Lake McDermott, trail trips are taken to Ptarmigan Lake, to Iceberg Lake, over Swiftcurrent pass to Granite Park, where an amazing view may be had of the central valley, to Grinnell Glacier, over Piegan Pass to St. Mary Lake, and up Canyon Creek to the wonderful chasm of Cracker Lake, above which Mount Siyeh rises almost vertically 4,000 feet.

There are more than a dozen lakes, great and small, in the Swiftcurrent Valley. The most conspicuous are the two Sherburne Lakes, Lake McDermott, Lake Josephine, Grinnell Lake, the three Swiftcurrent Lakes, Iceberg Lake, and Ptarmigan Lake. These all have remarkable beauty. The Lewis Overthrust may be observed at the falls of the Swiftcurrent River just below Lake McDermott. Eastward from the foot of the main fall is rock of the Cretaceous period. West and north from the foot of the fall is old Algonkian rock lying on top of the much younger Cretaceous.

THE KENNEDY VALLEYS.

The North and South Kennedy Valleys, next above Swiftcurrent, are remarkable for the fantastic and beautiful effects of the great fault. Their trout-haunted streams originate in cirques east of the picturesque red and yellow mountains which form the east walls of Swiftcurrent, and rush turbulently to the plains. Here the evidences of the Lewis Overthrust are most apparent. Principal of these is Chief Mountain, a tooth-shaped monster of yellow Altyn limestone standing alone and detached upon rocks millions of years younger. It is a single block of limestone rising nearly vertically on one side 1,500 feet from its base.

THE BELLY RIVER VALLEY.

The Belly River Valley, which occupies the northeastern corner of the park has been little visited because of its inaccessibility, but it is destined to become one of the most popular, now that trail development work has been started to open up this section for tourist travel. It contains many lakes of supurb scenery, overlooked by many majestic mountains. Eighteen glaciers feed its streams. The Belly River rises in a cirque which lies the other side of the northern wall of Iceberg Lake, and just over Ptarmigan Pass. Its walls are lofty and nearly vertical. Its cirque inclosing Helen Lake is one of the wildest spots in existence and well repays the time and labor of a visit. The Middle Fork, which skirts for some miles the south side of that tremendous aggregation of mountain masses called Mount Cleveland, originates in a double cirque system of positively sensational beauty. The glaciers in which these originate, only two of which, the Chaney and Shepard Glaciers, are named, are shelved just under the Continental Divide, and from them their outlet streams descend by lake-studded steps to their junction in Glenns Lake. Between the Middle Fork and the Belly River rises one of the most remarkable mountain masses in the park, a rival even of Cleveland, which consists of Mount Merritt and Crossley Ridge with their four impressive hanging glaciers. Below the meeting of the two forks the Belly River, now a fine swelling stream noted for its fighting trout, rushes headlong through the most luxuriant of valleys northward to the plains of Canada.

THE CENTRAL VALLEY.

Of Little Kootenai Valley, also, little is known to the public. It is the northern part of a magnificent central valley which splits Glacier National Park down from the top as far as Mount Cannon and carries on its sides parallel mountain ranges of magnificent grandeur, the Livingston Range bordering its west side, the Lewis Range its east side. In this Avenue of the Giants, about at its center, rises a fine wooded tableland known as Flattop Mountain, which, low as it is, bridges the Continental Divide over from the Livingston to the Lewis Range. From this tableland drop, north and south, the two valleys which, end to end, form the great avenue; Little Kootenai Creek running north, McDonald Creek running south. The Little Kootenai Valley is one of unusual forest luxuriance, and is bordered by glacier-spattered peaks of extraordinary majesty; Mount Cleveland, whose 10,438 feet of altitude rank it highest in the park, lies upon its east side. It ends in Waterton Lake, across whose waters, a little north of their middle, passes the international boundary line separating our Glacier National Park from Canada's Waterton Lakes Park.

The southern limb of this Avenue of the Giants, which follows McDonald Creek till it swings westward around Heavens Peak to empty into Lake McDonald, is only a little less majestic. It is upon the side of this superb valley that the Granite Park Chalets cling, from the porches of which the eye may trace the avenue northward even across the Canadian borders.

THE PRINCIPAL PASSES.

There are several passes of more or less celebrity connecting the east and west sides of Glacier National Park, several of which are not used except to afford magnificent west side views to east side tourists. So far, four passes over the Continental Divide are in practical use as crossing places.

GUNSIGHT PASS.

The most celebrated of these passes is Gunsight Pass. From the east it is reached directly from St. Mary Lake, and, by way of Piegan Pass, from Lake McDermott. From the west it is reached from Lake McDonald. It is a U-shaped notch in the divide between Gunsight Mountain and Mount Jackson. Just west of it lies Lake Ellen Wilson, one of Glacier's greatest celebrities for beauty. Just east of it lies Gunsight Lake, one of Glacier's greatest celebrities for wildness. From the foot of Gunsight Lake an easy trail of 2 miles leads to Blackfeet Glacier, the largest in the park, the west lobe of which is readily reached and presents, within less than a mile of ice, an admirable study of practically all the phenomena of living glaciers.

SWIFTCUREENT PASS.

Swiftcurrent Pass crosses the divide from Lake McDermott on the east. On the west side, one trail leads north to the Waterton Lakes and Canada, another south to Lake McDonald. Four beautiful shelf glaciers may be seen clinging to the east side of this pass, and from the crest of the pass, looking back, a magnificent view is had of the lake-studded Swiftcurrent Valley. From the Granite Park Chalets, just west of the pass, a marvelous view of west side and north side mountains may be obtained. A horse trail from the chalet takes the visitor to Logan Pass on the south. A foot trail leads him to the top of the Garden Wall where he may look down upon the Swiftcurrent and the Grinnell Glaciers. A foot trail involving an hour's climb to the top of Swiftcurrent Peak will spread before the tourist one of the broadest and most fascinating views in any land, a complete circle including all of Glacier National Park; also generous glimpses of Canada on the north, the Great Plains on the east, and the Montana Rockies on the west.

LOGAN PASS.

As you look south from the Granite Park Chalets your eye is held by a deep depression between beautiful Mount Oberlin and the towering limestones of Pollock Mountain. Through this and beyond it lie the Hanging Gardens dropping from a rugged spur of lofty Reynolds Mountain. Desire is strong within you to enter these inviting portals.

This picturesque depression is Logan Pass. From the east side of the Divide it is approached from the trail which connects St. Mary Lake and Lake McDermott by way of Piegan Pass. On the west side of the Divide, one trail leads directly to Lake McDonald through the McDonald Creek Valley and another to the Granite Park Chalets.

This new route makes possible a delightful variety of trail combinations. It opens a third route between Lake McDonald and the east side. From Lake McDonald it offers a round trip in both directions by way of Logan and Gunsight Passes and the Sperry Glacier; also a round trip including Granite Park. From St. Mary Lake it offers a direct route to Granite Park and Waterton Lake. From Lake McDermott it offers another route to St. Mary Lake by way of Swiftcurrent and Logan Passes, and a round trip by way of Swiftcurrent, Logan, and Piegan Passes.

BROWN PASS.

Brown Pass, the trail to which has been little improved since the old game days because so few use it, is destined to become one of the celebrated passes of America. The trail from the east side passes from Waterton Lake up Olson Valley amid scenery as sensational as it is unusual, along the shores of lakes of individuality and great beauty, and enters, at the pass, the amazingly wild and beautiful cirques at the head of Bowman Lake. From here, a trail drops down to Bowman Lake which it follows to its outlet, and thence to a junction with the Flathead River road. This road leads south to Lake McDonald and Belton. A second trail is planned to connect Brown Pass, across sensational summits, with the head of Kintla Valley.

SOUTH AND WEST SIDE VALLEYS.

M'DONALD VALLEY.

The western entrance to the park is at Belton, on the Great Northern Railroad, 3 miles from the foot of beautiful Lake McDonald, the largest lake in the park. Glacier Hotel (Lewis's), with its outlying cottages, is reached by automobile stage from the railroad to the foot of the lake and from there by connecting boat. It is also reached from the east side by trail over Gunsight and Swiftcurrent Passes. The lake is nearly 9 miles long and is wooded everywhere to the water's edge. It heads up among lofty mountains. The view from its waters, culminating in the Continental Divide, is among the noblest in the world. Lake McDonald was the first lake to be opened and settled. Within easy distance of its hotel by trail are some of the finest spectacles of the Rocky Mountains, among them the Sperry Glacier, Lake Ellen Wilson and its magnificent cascades into Little St. Mary Lake, the Gunsight Pass, the celebrated Avalanche Basin, and the fine fishing lakes of the Camas Creek Valley. At the foot of the lake passes the west side road from which may be entered, at their outlets, all the exquisite valleys of the west side.

VALLEYS SOUTH OF M'DONALD.

The west side valleys south of Lake McDonald are not yet sufficiently developed to be of tourist importance.

The Harrison Valley, next to the south, is inaccessible above the lake. It lies between Mount Jackson and Blackfeet Mountain, rising abruptly 4,000 feet to the Continental Divide and the great Harrison Glacier.

The Nyack Valley, still farther south, carries another stream of large size. It is surmounted by lofty mountains, of which Mount Stimson, 10,155 feet, is the highest. Other peaks are Mounts Pinchot and Phillips, and Blackfeet Mountain. Pumpelly is the largest of the several glaciers.

The valleys south of Nyack have little comparative interest.

VALLEYS NORTH OF M'DONALD.

The valley next north of McDonald, that of Camas Creek, contains six exquisite lakes. The chain begins in a pocket gorge below Longfellow Peak.

Logging Valley, next in order, a spot of great charm, does not suffer by comparison with its more spectacular neighbors. Quartz Valley contains four most attractive lakes, one of which, Cerulean Lake, sheltered by some of the most imposing peaks in the entire region, deserves to be better known. Rainbow Glacier, the largest of several at its top, hangs almost on the crest of Rainbow Peak, a mountain of remarkable dignity and personality.

BOWMAN VALLEY.

Bowman Valley, next to the north, is, second to McDonald, the principal line of travel on the west side of the park. Bowman Lake, though known to few, possesses remarkable beauty. Its shores are wooded like those of Lake McDonald, which it suggests in many ways. When its trail reaches the level of Brown Pass, there is disclosed a lofty cirque area of great magnificence. Mount Peabody, Boulder Peak, Mount Carter, the Guardhouse, and the serrated wall of the Continental Divide are topped and decorated with glaciers, their rocky precipices streaked perpendicularly with ribbons of frothing water. Hole-in-the-Wall Falls, outlet of a perpetual snow field, is a beautiful oddity.

KINTLA VALLEY.

The Kintla Valley, which occupies the northwestern corner of the park, is in many respects Glacier's climax. The Boundary Mountains, the northern side of the steep canyon which cradles its two superb lakes, are here exceedingly steep and rugged. The south side mountains, Parke Peak, Kintla Peak, Kinnerly Peak, Mount Peabody, and Boulder Peak, are indescribably wild and impressive. Kintla Peak, especially, rising 5,730 feet abruptly from the waters of upper Kintla Lake and bearing a large glacier on either shoulder like glistening wings, is one of the stirring spectacles of America. The time is coming when Kintla will be a familiar name even abroad. The Kintla and Agassiz Glaciers are next in size to the Blackfeet Glacier.

Up to the present time it has been possible to reach Kintla only by a long forest trail from the Flathead River or by a difficult and obscure trail from the Canadian side; hence its few visitors. The trail planned from Brown Pass crosses the Boulder Glacier and passes in its descent the tongue of the Kintla Glacier, a remarkable spectacle. Its completion will make a supreme American beauty spot readily accessible by trail.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

1920/glac/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 16-Feb-2010