|

An Isolated Empire: A History of Northwest Colorado BLM Cultural Resource Series (Colorado: No. 12) |

|

Chapter I:

NORTHWESTERN COLORADO PRIOR TO EXPLOITATION

Northwestern Colorado includes the area extending west from the Continental Divide to the Utah-Colorado state line, and from about the Colorado River northward to the Wyoming-Colorado state line. Within this area lie a succession of wide valleys, several high mountain parks, and a series of major river drainages.

Farther west, Colorado is composed of broad floodplains on either side of the major rivers, and within the main drainage areas, smaller creeks and streams cut the landscape into massive buttes and narrow canyons. This region is well watered by numerous subsidiary creeks running into the Yampa or Colorado Rivers. One of the major features of the far northwestern corner is a valley, Brown's Park, extending sixty miles into Utah from the Maybell, Colorado area on a northwest axis.

The major river drainages include the Colorado (Grand) River, which begins at Grand Lake and is fed by the Fraser, the Blue, and the Eagle Rivers. North Park, one of the smaller valleys, is drained by the North Platte River and smaller streams and creeks, such as the Michigan, the Illinois and the Canadian. The Yampa Valley's major river is the Yampa (Bear) and it is fed by the Little Snake and the Elk Rivers as well as smaller creeks, like Fortification. The White River Valley is fed by Piceance Creek, Douglas Creek, and numerous other small streams.

The area's climate is extreme. From the summer months when the temperature can exceed 100 degrees in the far northwestern corner, to the winter months in the mountain parks where the thermometer has recorded 54 degrees below zero, radical variations make agriculture and development difficult. [1] Generally, the mountain parks remain wet from May until July, while the lower areas are dry by late June. This climate, plus the fluctuating seasonal water sources, mainly run-off from snowfall, make agriculture a limited and risky business.

To fully understand the geography of Northwestern Colorado, it is important to know what geologic events have transpired to modify the landscape. The base material upon which the area is built is Pre-Cambrian rock that was eroded into vast layers of flat sediment. These layers were then uplifted and re-eroded so that a series of sediments have been left over a period of millions of years. [2] Most of the sedimentation of the region and new layers of sandstone were laid down. Almost perfect fossil examples of marine life can be found. [3]

Late in the Jurassic Period, Colorado was submerged. During this moist environment, the dinosaur bones that are found in Dinosaur National Monument were deposited. Plant and marine life began to provide fossil remains that became the coal and oil deposits that cover this region. During the Cretaceous Period the land was uplifted and the Piceance and Axial Basins were created. Underlying these basins were the oil and coal deposits left by organic matter buried in the region. [4]

The Tertiary Period of the Cenozoic Era saw a period of mountain building called the Laramide Orogeny. The Rocky Mountains, as we know them, were uplifted. The core of the uplift was cracked and brought to the surface, where solutions of gold, silver, zinc, lead, copper and iron seeped into the fissures. This created the veins of gold that are common in the Colorado Rockies. Localized deposits were also created by this uplift, including areas such as Hahn's Peak and Independence Mountain. Additionally, an oily material called Kerogen was formed from the mud of Lake Uintah, which had developed with the Laramie uplift, and from these deposits came the Green River formation of oil shales.

The final building period came in the Quaternary Period when the Ice Age descended on Colorado. During the Pleistocene Epoch, the state was selectively glaciated, and many of the features that we know today were created. To some extent the parks, Middle and North, were carved out, while the mountains including the Rockies, the Park Range and the Elk Mountains were gouged out. Terminal moraines were dropped from glaciers and these formed dams across valleys; from these formations came lakes such as Grand Lake. [5]

Recent geologic events have created the land-forms that are currently known. These are a result of natural erosion by wind and water, along with geologic changes wrought by massive slides and other factors. Manmade features have created the most recent changes in the landscape. Such physical evidence as mines, foundations, road alignments and other changes are the more recent and possibly most radical variations on the land since the Ice Age. Man's use and occupation of the land is clearly evident in the changes he has wrought.

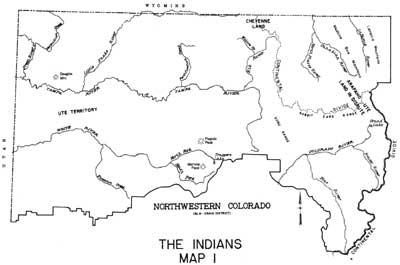

The advent of humans in the area is difficult to date. Man probably had used the land for 10,000 years or more prior to the coming of the Europeans. However, it is historic native Indians which are of interest as factors in the settlement and development of the area. Prior to the coming of Europeans, the northwest corner of the state was populated basically by three tribes of Indians. Of these groups, the largest was probably the Ute. The next most important tribe in the area was the Arapaho who, while plains natives, often used North and Middle Parks for summer hunting grounds. These were traditionally Ute lands, and conflicts often erupted over hunting rights. However, the Arapaho continued to use the near western areas despite Ute objections. The other tribe of consequence in the area was the Shoshoni, who were said to have come into the Brown's Park area to winter. These people were probably the Wind River Shoshoni and were of the same linguistic group as the Ute. In this way they were able to exist with the Ute and there was rarely trouble between these peoples. Other tribes that had a minor impact on the area included the Cheyenne, the Navajo, and to some extent, the Apache.

Within the Ute tribe there were subdivisions including Uintah, Wimonuntici, Mowatavi-watsiu, Mowatri, Kopata, and others. These subdivisions related primarily to geographic locations and not major cultural differences. The Uintah Ute were the main inhabitants of northwestern Colorado. These people were nomadic hunters who used the river valleys for shelter. They summered in the high mountain parks stocked with abundant game, particularly elk, deer, and beaver, and when the weather turned cold, they moved into the Yampa or White River valleys to spend the winter in comfort. The Ute were not known as hostile to whites at the time Europeans first described them. During the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the Ute were continually at war with the Arapaho, the Comanche, and other plains tribes. However, once the Uintah had moved into the mountainous interior, the constant warfare eased. They were friendly to whites, and their only real enemies during the period of early European occupation were the plains war parties and Arapaho who occasionally encroached the Ute lands.

The Ute tended to live in small family groups scattered over wide areas, yet they retained a certain cohesion in times of trouble. [6] The Ute culture was changed radically by the introduction of the horse; once adapted, the horse was looked upon as a sacred animal. It was Ute wealth, and it was valued possibly more than a wife, children, or a dog. [7] Thanks to the horse, which the Ute had by the 1680's, his geographic range was considerably extended; due to new and better available food, the Ute advanced considerably in status among the natives of the West. [8] Eventually, the Ute culture developed into a buckskin-horse-buffalo economy, with the Plains Indians making a strong contribution to Ute materialism. The Ute expanded to the point that by the time Europeans came into their land, they ranged from Pike's Peak on the east to the Great Salt Lake on the west, and from Taos in the south, to Wyoming Green River country on the north. [9]

The first known European visitors to northwestern Colorado were Spanish, in 1776. The Spanish were not new to the general area of Colorado; as early as 1695 Diego de Vargas, the re-conquerer of New Mexico, had visited the San Luis Valley. Colorado was of little interest to the Spanish, however, for it showed little agricultural promise, and no precious minerals were found. In 1765, Juan de Rivera was sent out from Santa Fe to explore for minerals in Colorado. He reached the area of the Black Canyon of the Gunnison and also explored the San Juan region. Finding nothing of value, he returned home and reported that the area was of little worth. This ended interest in Colorado until 1776. [10]

In that year, the Spanish government of New Mexico decided to explore for new routes to California from Santa Fe. The reason for the decision to go north was that the Hopi (Moqui) had blocked the most direct route across Arizona, and the Spanish, particularly the Church, were interested in establishing relations with the new California settlements. [11] There was a trader's trail into Colorado which had been used since the Rivera expedition. It was upon this path that two Franciscan explorers led their small expedition. These men, Fray Silvestre Vélez de Escalante and Fray Francisco Atanasio Dominguéz, were determined to trace a new route to California. They projected that this could be done with minimum cost and without a large party. [12]

The Spanish governor at Santa Fe was interested in the project, and he willingly helped the two friars arrange for their trip. Governor Fermín de Mendinueta provided material help and saw the expedition off on July 29, 1776. The little party of ten left Santa Fe and worked its way up to Abíquiu (New Mexico), from whence the group pushed north into Colorado. By August, 1776, they were well into the present state of Colorado. They passed Dulce, and then moved to the San Juan River, past Mesa Verde, to the Dolores River. [13]

From the Dolores, the party moved to the Uncompahgre River where it meets the Gunnison River. They crossed the stream with the help of "Yuta" Indians. The party then moved northward toward the Green River. In doing so, they became the first Europeans to have crossed the Grand Hogback, the Colorado River, and the Piceance Basin. By September, 1776, they were moving into the Grand Valley.

On September 5, 1776, the group had reached the Debeque, Colorado area, from whence they trailed north along Roan Creek. The party left Roan Creek, travelled along the Roan Plateau and came to the headwaters of Douglas Creek. From here they proceeded through Douglas Canyon into the White River country. Along the way, they saw the Cañon Pintado (Painted Canyon) and what they thought were veins of gold along the canyon walls. [14] However, they made no attempt to mine. Upon emerging from the Douglas Canyon area, the group moved down the White River Valley into Utah. They camped at Jensen, Utah, on September 14, 1776, and then proceeded southwest across that state and into Arizona, finally returning to Santa Fe without having found a route to California. The knowledge gained from the expedition was not widely distributed and many of the areas that had been explored for the first time remained "undiscovered". The Dominguéz-Escalante expedition was of some value in that the resources of the Great Basin area were explored. However, the Spanish were not interested in taking advantage of these discoveries, and it was not for another forty years that Mexicans and Americans would venture far into this land.

|

| Map 1. The Indians (click on map for an enlargement in a new window) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

co/2/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 31-Oct-2008