MINOR ANTIQUITIES

(continued)

The rooms and refuse-heaps of Spruce-tree House had

been pretty thoroughly ransacked for specimens by those who preceded the

author, so that few minor antiquities were expected to come to light in

the excavation and repair work. Notwithstanding this, however, a fair

collection, containing some unique specimens and many representative

objects, was made, and is now in the National Museum where it will be

preserved and be accessible to all students. Considering the fact that

most of the specimens previously abstracted from this ruin have been

scattered in all directions and are now in many hands, it is doubtful

whether a collection of any considerable size from Spruce-tree House

exists in any other public museum. In order to render this account more

comprehensive, references are made in the following pages to objects

from Spruce-tree House elsewhere described, now in other collections.

These references, quoted from Nordenskiöld, the only writer on this

subject, are as follows:

Plate XVII:2. a and b. Strongly flattened cranium of

a child. Found in a room in Sprucetree House.

Plate XXXIV:4. Stone axe of porphyrite. Sprucetree

House.

Plate XXXV: 2. Rough-hewn stone axe of quartzite.

Sprucetree House.

Plate XXXIX: 6. Implement of black slate. Form

peculiar (see the text). Found in Sprucetree House.

[In the text the last-mentioned specimen is again

referred to, as follows:]

I have still to mention a number of stone implements

the use of which is unknown to me, first some large (15-30 cm.), flat,

and rather thick stones of irregular shape and much worn at the edges

(Pl. XXXIX: 4, 5), second a singular object consisting of a thin slab of

black slate, and presenting the appearance shown in Pl. XXXIX: 6. My

collection contains only one such implement, but among the objects in

Wetherill's possession I saw several. They are all of exactly the same

shape and of almost the same size. I cannot say in what manner this slab

of slate was employed. Perhaps it is a last for the plaiting of sandals

or the cutting of moccasins. In size it corresponds pretty nearly to the

foot of an adult.

Plate XL: 5. Several ulnae and radii of

birds (turkeys) tied on a buckskin string and probably used as an

amulet. Found in Sprucetree House.

Plate XLIII: 6. Bundle of 19 sticks of hard wood,

probably employed in some kind of knitting or crochet work. The pins are

pointed at one end, blunt at the other, and black with wear. They are

held together by a narrow band of yucca. Found in Sprucetree House.

Plate XLIV: 2. Similar to the preceding basket, but

smaller. Found in Sprucetree House. . . .

[The "preceding basket" is thus described in

explanation of the figure (Pl. XLIV: 1) :] Basket of woven yucca in two

different colors, a nest pattern being thus attained. The strips of

yucca running in a vertical direction are of the natural yellowish

brown, the others (in horizontal direction) darker. . . .

Plate XLV: 1(95) and 2(663): Small baskets of yucca,

of plain colour and of handsomely plaited pattern. Found: 1 in ruin 9, 2

in Sprucetree House.

Plate XLVIII: 4(674). Mat of plaited reeds,

originally 1.2 X 1.2 in., but damaged in transportation. Found in

Sprucetree House.

It appears from the foregoing that the following

specimens have been described and figured by Nordenskiöld, from

Spruce-tree House: (1) A child's skull; (2) 2 stone axes; (3) a slab of

black slate; (4) several bird bones used for amulet; (5) bundle of

sticks; (6) 2 small baskets; (7) a plaited mat.

In addition to the specimens above referred to, the

majority of which are duplicated in the author's collection, no objects

from Spruce-tree House are known to have been described or figured

elsewhere, so that there are embraced in the present account practically

all printed references to known material from this ruin. But there is no

doubt that other specimens as yet unmentioned in print still exist in

public collections in Colorado, and later these also may be described

and figured. From the nature of the author's excavations and method of

collecting, little hope remains that additional specimens may be

obtained from rooms in Spruce-tree House, but the northern refuse-heap

situated at the back of the cavern may yet yield a few, good objects.

This still awaits complete scientific excavation.

The author's collection from Spruce-tree House, the

choice specimens of which are now in the National Museum, numbers

several hundred objects. All the duplicates and heavy specimens, about

equal in number to the lighter ones, were left at the ruin where they

are available for future study. These are mostly stone mauls, metates

and large grinding implements, and broken bowls and vases. The absence

from Spruce-tree House of certain characteristic objects widely

distributed among Southwestern ruins is regarded as worthy of comment.

It will be noticed in looking over the author's collection that there

are no specimens of marine shells, or of turquoise ornaments or obsidian

flakes, from the excavations made at Spruce-tree House. This fact is

significant, meaning either that the former inhabitants of this village

were ignorant of these objects or that the excavators failed to find

what may have existed. The author accepts the former explanation, that

these objects were not in use by the inhabitants of Spruce-tree House,

their ignorance of them having been due mainly to their restricted

commercial dealings with their neighbors.

Obsidian, one of the rarest stones in the

cliff-dwellings of the Mesa Verde, as a rule is characteristic of very

old ruins and occurs in those having kivas of the round type, to the

south and west of that place.

It is said that turquoise has been found in the Mesa

Verde ruins. The author has seen a beautiful bird mosaic with inlaid

turquoise from one of the ruins near Cortez in Montezuma valley. This

specimen is made of hematite with turquoise eyes and neckband of the

same material; the feathers are represented by stripes of inlaid

turquoise. Also inlaid in turquoise in the back is an hour-glass figure,

recalling designs drawn in outline on ancient pottery.

The absence of bracelets, armlets, and finger rings

of sea shells, objects so numerous in the ruins along the Little

Colorado and the Gila, may be explained by lack of trade, due to culture

isolation. The people of Mesa Verde appear not to have come in contact

with tribes who traded these shells, consequently they never obtained

them. The absence of culture connection in this direction tells in favor

of the theory that the ancestors of the Mesa Verde people did not come

from the southwest or the west, where shells are so abundant. Although

not proving much either way by itself, this theory, when taken with

other facts which admit of the same interpretation, is significant. The

inhabitants of Spruce-tree House (the same is true of the other Mesa

Verde people) had an extremely narrow mental horizon. They obtained

little in trade from their neighbors and were quite unconscious of the

extent of the culture of which they were representatives.

POTTERY

The women of Spruce-tree House were expert potters

and decorated their wares in a simple but artistic manner. Until we have

more material it would be gratuitous to assume that the ceramic art

objects of all the Mesa Verde ruins are identical in texture, colors,

and symbolism, and the only way to determine how great are the

variations, if any, would be to make an accurate comparative study of

pottery from different localities. Thus far the quantity of material

available does not justify comparison even of the ruins of this mesa,

but there is a good beginning of a collection from Spruce-tree House.

The custom of placing in graves offerings of food for the dead has

preserved several good bowls, and although whole pieces are rare

fragments are found in abundance. Eighteen earthenware vessels,

including those repaired and restored from fragments, rewarded the

author's excavations at Spruce-tree House. Some of these vessels bear a

rare and beautiful symbolism which is quite different from that known

from Arizona. The few plates (16-20) here given to illustrate these

symbols are offered more as a basis for future study and comparisons

than as an exhaustive representation of ceramics from one ruin.

The number and variety of pieces of pottery figured

from the Mesa Verde cliff-dwellings have not been great. An examination

of Nordenskiöld's memoir reveals the fact that he represents about

50 specimens of pottery; several of these were obtained by purchase, and

others came from Chelly canyon, the pottery of which is strikingly like

that of Mesa Verde. The majority of specimens obtained by

Nordenskiöld's excavations were from Step House, not a single

ceramic object from Spruce-tree House being figured. So far as the

author can ascertain, the ceramic specimens here considered are the

first representatives of this art from Spruce-tree House that have been

described or figured, but there may be many other specimens from this

locality awaiting description and it is to be hoped that some day these

may be made known to the scientific world.

FORMS

Every form of pottery represented by

Nordenskiöld, with the exception of that which he styles a

"lamp-shaped" vessel and of certain platter forms with indentations,

occurs in the collection here considered.

Nordenskiöld figures a jar provided with a lid,

both sides of which are shown.a It would seem that this lid (fig.

1),b unlike those provided with knobs, found by the author, had

two holes near the center. The decoration on the top of the lid of one

of the author's specimens resembles that figured by Nordenskiöld,

but other specimens differ from his as shown in figure 1. The specimens

having raised lips and lids are perforated in the edges of the openings,

with one or more holes for strings or handles. As bowls of this form are

found in sacred rooms they would seem to have been connected with

worship. The author believes that they served the same purposes as the

netted gourds of the Hopi. Most of the ceramic objects in Spruce-tree

House were in fragments when found.c Some of these objects have

been repaired and it is remarkable that so much good material for the

study of the symbolism has been obtained in this way.

aSee The Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde, pls.

XXVIII, XXIX: 7.

bThe text figures which appear in this paper were drawn from

nature by Mrs. M. W. Gill, of Forest Glen, Md.

cThe author is greatly indebted to Mr. A. V. Kidder for aid

in sorting and labeling the fragments of pottery, without his assistance

in the field it would have been impossible to repair many of these

specimens.

FIG. 1. Lid of jar.

|

Black and white ware is the most common and the

characteristic painted pottery, but fragmentary specimens of a reddish

ware occur. One peculiarity in the lips of food bowls from Spruce-tree

House (pls. 16-18) is that their rims are flat, instead of rounded as in

more western prehistoric ruins, like Sikyatki. Food bowls are rarely

concave at the base.

No fragments of glazed pottery were found, although

the surfaces of some species were very smooth and glossy from constant

rubbing with smoothing stones. Several pieces of pottery were unequally

fired, so that a vitreous mass, or blotch, was evident on one side.

Smooth vessels and those made of coiled ware, which were covered with

soot from fires, were evidently used in cooking.

FIG. 2. Repaired pottery.

|

Several specimens showed evidences of having been

broken and afterwards mended by the owners (fig. 2); holes were drilled

near the line of fracture and the two parts tied together; even the

yucca strings still remain in the holes, showing where fragments were

united. In figure 3 there is represented a fragment of a handle of an

amphora on which is tied a tightly-woven cord.

FIG. 3. Handle with attached cord.

|

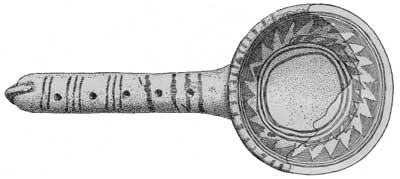

Not a very great variety of pottery forms was brought

to light in the operations at Spruce-tree House. Those that were found

are essentially the types common throughout the Southwest, and may be

classified as follows: (1). Large jars, or ollas; (2) flat food bowls;

(3) cups and mugs; (4) ladles or dippers (fig. 4); (5) canteens; (6)

globular bowls. An exceptional form is a globular bowl with a raised lip

like a sugar bowl (pl. 19, f). This form is never seen in other

prehistoric ruins.

STRUCTURE

Classified by structure, the pottery found in the

Spruce-tree House ruin falls into two groups, coiled ware and smooth

ware, the latter either with or without decoration. The white ware has

black decorations.

The bases of the mugs (pl. 19) from Spruce-tree

House, like those from other Mesa Verde ruins, have a greater diameter

than the lips. These mugs are tall and their handles are of generous

size. One of the mugs found in this ruin has a T-shaped hole in its

handle (fig. 5), recalling in this particular a mug collected in 1895 by

the author at Awatobi, a Hopi ruin.

The most beautiful specimen of canteen found at

Spruce-tree House is here shown in plate 20.

FIG. 4. Ladle.

|

The coiled ware of Spruce-tree House, as of all the

Mesa Verde ruins, is somewhat finer than the coiled ware of Sikyatki.

Although no complete specimen was found, many fragments were collected,

some of which are of great size. This kind of ware was apparently the

most abundant and also the most fragile. As a rule these vessels show

marks of fire, soot, or smoke on the outside, and were evidently used as

cooking vessels. On account of their fragile character they could not

have been used for carrying water, for, with one or two exceptions, they

would not be equal to the strain. In decoration of coiled ware the women

of Spruce-tree House resorted to an ingenious modification of the coils,

making triangular figures, spirals, or crosses in relief, which were

usually affixed to the necks of the vessels.

FIG. 5. Handle of mug.

|

The symbolism on the pottery of Spruce-tree House is

essentially that of a cliff-dwelling culture, being simple in general

characters. Although it has many affinities with the archaic symbols of

the Pueblos, it has not the same complexity. The reason for this can be

readily traced to that same environmental influence which caused the

communities to seek the cliffs for protection. The very isolation of the

Mesa Verde cliff-dwellings prevented the influx of new ideas and

consequently the adoption of new symbols to represent them. Secure in

their cliffs, the inhabitants were not subject to the invasion of

strange clans nor could new customs be introduced, so that conservatism

ruled their art as well as their life in general. Only simple symbols

were present because there was no outside stimulus or competition to

make them complex.

On classification of Spruce-tree House pottery

according to technique, irrespective of its form, two divisions appear:

(1) Coiled ware showing the coils externally, and (2) smooth ware with

or without decorations. Structurally both divisions are the same,

although their outward appearance is different.

The smooth ware may be decorated with incised lines

or pits, but is painted often in one color. All the decorated vessels

obtained by the author at Spruce-tree House belong to what is called

black-and-white ware, by which is meant pottery having a thin white slip

covering the whole surface upon which black pictures are painted.

Occasionally fragments of a reddish brown cup were found, while red ware

bearing white decorative figures was recovered from the Mesa Verde; but

none of these are ascribed to Spruce-tree House or were collected by the

author. The general geographical distribution of this black and white

ware, not taking into account sporadic examples, is about the same as

that of the circular kivas, but it is also found where circular kivas

are unknown, as in the upper part of the valley of the Little Colorado.

The black-and-white ware of modern pueblos, as Zu-i

and Hano, the latter the Tewan pueblo among the Hopi, is of late

introduction from the Rio Grande; prehistoric Zu-i ware is unlike that

of modern Zu-i, being practically identical in character with that of

the other ancient pueblos of the Little Colorado and its tributaries.

DECORATION

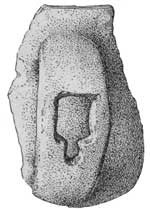

FIG. 6. Fragment of pottery.

|

As a rule, the decoration on pottery from Spruce-tree

House is simple, being composed mainly of geometrical patterns. Life

forms are rare, when present consisting chiefly of birds or rude figures

of mammals painted on the outside of food bowls (fig. 6). The

geometrical figures are principally rectilinear, there being a great

paucity of spirals and curved lines. The tendency to arrange rows of

dots along straight lines is marked in Mesa Verde pottery and occurs

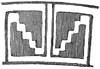

also in dados of house walls. There are many examples of stepped or

terraced figures which are so arranged in pairs that the spaces between

the terraces form zigzag bands, as shown in figure 7. A band extending

from the upper left hand, to the lower right hand, angle of the

rectangle that incloses the two terraced figures, may be designated a

sinistral, and when at right angles a dextral, terraced figure (fig. 8).

Specimens from Spruce-tree House show considerable modification in these

two types.

FIG. 7. Zigzag ornament.

|

With exception of the terrace the triangle (fig. 9)

is possibly the most common geometrical decoration on Spruce-tree House

pottery. Most of the triangles may be bases of terraced figures, for by

cutting notches on the longer sides of these triangles, sinistral or

dextral stepped figures (as the case may be) result.

The triangles may be placed in a row, united in

hourglass forms, or distributed in other ways. These triangles may be

equilateral or one of the angles may be very acute. Although the

possibilities of triangle combinations are almost innumerable the

different forms can be readily recognized. The dot is a common form of

decoration, and parallel lines also are much used. Many bowls are

decorated with hachure, and with line ornaments mostly rectilinear.

FIG. 8. Sinistral and dextral stepped figures.

|

The volute plays a part, although not a conspicuous

one, in Spruce-tree House pottery decoration. Simple volutes are of two

kinds, one in which the figure-coils follow the direction of the hands

of the clock (dextral); the other, in which they take an opposite

direction (sinistral). The outer end of the volute may terminate in a

triangle or other figure, which may be notched, serrated, or otherwise

modified. A compound sinistral volute is one which is sinistral until it

reaches the center, when it turns into a dextral volute extending to the

periphery. The compound dextral volute is exactly the reverse of the

last-mentioned, starting as dextral and ending as sinistral. If, as

frequently happens, there is a break in the lines at the middle, the

figure may be called a broken compound volute. Two volutes having

different axes are known as a composite volute, sinistral or dextral as

the case may be.

The meander (fig. 10) is also important in

Spruce-tree House or Mesa Verde pottery decoration. The form of meander

homologous to the volute may be classified in the same terms as the

volute, into (1) simple sinistral meander; (2) simple dextral meander;

(3) compound sinistral meander; (4) compound dextral meander; and (5)

composite meander. These meanders, like the volutes, may be accompanied

by parallel lines or by rows of dots enlarged, serrated, notched, or

otherwise modified.

FIG. 9. Triangle ornament.

|

In some beautiful specimens a form of hachure, or

combination of many parallel lines with spirals and meanders, is

introduced in a very effective way. This kind of decoration is very rare

on old Hopi (Sikyatki) pottery, but is common on late Zu-i and Hano

ceramics, both of which are probably derived from the Rio Grande region.

Lines, straight or zigzig, constitute important

elements in Spruce-tree House pottery decoration. These may be either

parallel, or crossed so as to form reticulated areas.

Along these lines rows of dots or of triangular

enlargements may be introduced. The latter may be simply serrations,

dentations, or triangles of considerable size, sometimes bent over,

resembling pointed bands.

Curved figures are rarely used, but such as are found

are characteristic. Concentric rings, with or without central dots, are

not uncommon.

Rectangles apparently follow the same general rules

as circles, and are also sometimes simple, with or without central dots.

FIG. 10. Meander.

|

The triangle is much more common as a decorative

motive than the circle or the rectangle, variety being brought about by

the difference in length of the sides. The hourglass formed by two

triangles with one angle of each united is common. The quail's-head

design, or triangle having two parallel marks on an extension at one

angle, is not as common as on Little Colorado pottery and that from the

Gila valley.

As in all ceramics from the San Juan area, the

stepped figures are most abundant. There are two types of stepped

figures, the sinistral and the dextral, according as the steps pass from

left to right or vice versa. The color of the two stepped figures may be

black, or one or both may have secondary ornamentation in forms of

hachure or network. One may be solid black, the other filled in with

lines.

In addition to the above-mentioned geometrical

figures, the S-shaped design is common; when doubled, this forms the

cross called swastika. The S figure is of course generally curved but

may be angular, in which case the cross is more evident. One bowl has

the S figure on the outside. All of the above-mentioned designs admit of

variations and two or more are often combined in Spruce-tree House

pottery, which is practically the same in type as that of the whole Mesa

Verde region.

CERAMIC AREAS

While it is yet too early in our study of prehistoric

pueblo culture to make or define subcultural areas, it is possible to

recognize provisionally certain areas having features in common, which

differ from other areas.a It has already been shown that the form of the

subterranean ceremonial room can be used as a basis of classification.

If pottery symbols are taken as the basis, it will be found that there

are at least two great subsections in the pueblo country coinciding with

the two divisions recognized as the result of study of the form of

sacred rooms—the northeastern and the southwestern region or, for

brevity, the northern and the southern area. In the former region lie,

besides the Mesa Verde and the San Juan valley, Chaco and Chelly

canyons; in the latter, the ruins of "great houses" along the Gila and

Salt rivers.

aThe classification into cavate houses, cliff-dwellings, and

pueblos is based on form.

From these two centers radiated in ancient times two

types of pottery symbols expressive of two distinct cultures, each

ceremonially distinct and, architecturally speaking, characteristic. The

line of junction of the influences of these two subcultural areas

practically follows the Little Colorado river, the valley of which is

the site of a third ceramic subculture area; this is mixed, being

related on one side to the northern, on the other to the southern,

region. The course of this river and its tributaries has determined a

trail of migration, which in turn has spread this intermingled ceramic

art far and wide. The geographical features of the Little Colorado basin

have prevented the evolution of characteristic ceramic culture in any

part of the region.

Using color and symbolism of pottery as a basis of

classification, the author has provisionally divided the sedentary

people of the Southwest into the following divisions, or has recognized

the following ceramic areas: (1) Hopi area, including the wonderful ware

of Sikyatki, Awatobi, and the ruins on Antelope mesa, at old

Mishongnovi, Shumopavi and neighboring ruins; (2) Casa Grande area; (3)

San Juan area, including Mesa Verde, Chaco canyon, Chelly canyon as far

west as St. George, Utah, and Navaho mountain, Arizona; (4) Little

Colorado area, including Zu-i. The pottery of Casas Grandes in Chihuahua

is allied in colors but not in symbols to old Hopi ware. So little is

known of the old Piros ceramics and of the pottery from all ruins east

of the Rio Grande, that they are not yet classified. The ceramics from

the region west of the Rio Grande are related to the San Juan and Chaco

areas.

The Spruce-tree House pottery belongs to the San Juan

area, having some resemblance and relationship to that from the lower

course of the Little Colorado. It is markedly different from the pottery

of the Hopi area and has only the most distant resemblance to that from

Casas Grandes.a

aThe above classification coincides in some respects with

that obtained by using the forms of ceremonial rooms as the basis.

HOPI AREA

The Hopi area is well distinguished by specialized

symbols which are not duplicated elsewhere in the pueblo area. Among

these may be mentioned the symbol for the feather, and a band

representing the sky with design of a mythic bird attached. As almost

all pueblo symbols, ancient and modern, are represented on old Hopi

ware, and in addition other designs peculiar to it, the logical

conclusion is that these Hopi symbols are specialized in origin.

The evolution of a ceramic area in the neighborhood

of the modern Hopi mesas is due to special causes, and points to a long

residence in that locality. It would seem from traditions that the

earliest Hopi people came from the east, and that the development of a

purely Hopi ceramic culture in the region now occupied by this people

took place before any great change due to southern immigration had

occurred. The entrance of Patki and other clans from the south strongly

affected the old Hopi culture, which was purest in Sikyatki, but even

there it remained distinctive. The advent of the eastern clans in large

numbers after the great rebellion in 1680, especially of the Tanoan

families about 1710, radically changed the symbolism, making-modern Hopi

ware completely eastern in this respect. The old symbolism, the germ of

which was eastern, as shown by the characters employed, almost

completely vanished, being replaced by an introduced symbolism.

In order scientifically to appreciate the bearing on

the migration of clans, of symbolism on pottery, we must bear in mind

that a radical difference in such symbolism as has taken place at the

Hopi villages may have occurred elsewhere as well, although there is no

evidence of a change of this kind having occurred at Spruce-tree House.

The author includes under Hopi ware that found at the

Hopi ruins Sikyatki, Shumopavi, and Awatobi, the collection from the

first-named being typical. Some confusion has been introduced by others

into the study of old Hopi ware by including in it, under the name

"Tusayan pottery," the white-and-black ware of the Chelly canyon.a There

is a close resemblance between the pottery of Chelly canyon and that of

Mesa Verde, but only the most distant relationship between true Hopi

ware and that of Chelly canyon. The latter belong in fact to two

distinct areas, and differ in color, symbolism, and general characters.

In so far as the Hopi ware shares its symbolism with the other

geographical areas of the eastern region, to the same extent there is

kinship in culture. In more distant ruins the pottery contains a greater

admixture of symbols foreign to Mesa Verde. These differences are due no

doubt to incorporation of other clans.

aOf 40 pieces of pottery called "Tusayan," figured in

Professor Holmes' Pottery of the Pueblo Area (Second Annual Report of

the Bureau of Ethnology), all but three or possibly four came from

Chelly canyon and belong to the San Juan rather than to the Hopi ware.

Black-and-white pottery is very rare in collections of old Hopi ware,

but is most abundant in the cliff-houses of Chelly canyon and the Mesa

Verde ruins.

The subceramic area in which the Mesa Verde ruins lie

embraces the valleys of the San Juan and its tributaries, Chelly canyon,

Chaco canyon, and probably the ruins along the Rio Grande, on both sides

of the river. Whether the Chaco or the Mesa Verde region is the

geographical center of this subarea, or not, can not be determined, but

the indications are that the Mesa Verde is on its northern border. Along

the southwestern and western borders the culture of this area mingles

with that of the subcultural area adjoining on the south, the resultant

symbolism being consequently more complex. The ceramic ware of ruins of

the Mesa Verde is little affected by outside and diverse influences,

while, on the contrary, similar ware found along the western and

southern borders of the subcultural area has been much modified by the

influence of the neighboring region.

LITTLE COLORADO AREA

Although the decoration on pottery from Spruce-tree

House embraces some symbols in common with that of the ruins along the

Little Colorado, including prehistoric Zu-i, there is evidence of a

mingling of the two ceramic types which is believed to have originated

in the Gila basin. The resemblance in the pottery of these regions is

greater near the sources of the Little Colorado, differences increasing

as one descends the river. At Homolobi (near Winslow) and Chevlon, where

the pottery is half northern and half southern in type, these

differences have almost disappeared.

This is what might be expected theoretically, and is

in accordance with legends of the Hopi, for the Little Colorado ruins

are more modern than the round-kiva culture of Chaco canyon and Mesa

Verde, and than the square-ceremonial-house culture of the Gila. The

indications are that symbolism of the Little Colorado ruins is a

composite, representative in about equal proportions of the two

subcultures of the Southwest.a

aThe pottery from ruins in the Little Colorado basin, from

Wukoki at Black Falls to the Great Colorado, is more closely allied to

that of the drainage of the San Juan and its tributaries.

As confirmatory of this suggested dual origin we find

that the symbolism of pottery from ruins near the source of the Little

Colorado is identical with that of the Salt, the Verde, and the Tonto

basins, from which their inhabitants originally came in larger numbers

than from the Rio Grande. In the ruins of the upper Salt and Gila the

pottery is more like that of the neighboring sources of the Little

Colorado because of interchanges. On the other hand, the ancient Hopi,

being more isolated than other Pueblos, especially those on the Little

Colorado, developed a ceramic art peculiar to themselves. Their pottery

is different from that of the Little Colorado, the upper Gila and its

tributary, the Salt, and the San Juan including the Mesa Verde.

The Zu-i valley, lying practically in the pathway of

culture migration or about midway between the northern and southern

subceramic areas, had no distinctive ancient pottery. Its ancient

pottery is not greatly unlike that of Homolobi near Winslow but has been

influenced about equally by the northern and the southern type. Whatever

originality in culture symbols developed in the Zu-i valley was

immediately merged with others and spread over a large area.b

bThere is of course very little ancient Zu-i ware in

museums, but such as we have justifies the conclusion stated

above.

MESA VERDE AREA

While there are several subdivisions in the eastern

subcultural area, that in which the Mesa Verde ruins are situated is

distinctive. The area embraces the ruins in the Montezuma valley and

those of Chelly canyon, and the San Juan ruins as far as Navaho

mountain, including also the Chaco and the Canyon Largo ruins. Probably

the pottery of some of the ruins east of the Rio Grande will be found to

belong to the same type. That of the Hopi ceramic area, the so-called

"Tusayan," exclusive of Chelly canyon, is distinct from all others. The

pottery of the Gila subculture area is likewise distinctive but its

influence made its way up the Verde and the Tonto and was potent across

the mountains, in the Little Colorado basin. Its influence is likewise

strong in the White Mountain ruins and on the Tularosa, and around the

sources of the Gila and Salt rivers.

An examination of the decoration of pottery from

Spruce-tree House fails to reveal a single specimen with the well known

broken encircling line called "the line of life." As this feature is

absent from pottery from all the Mesa Verde ruins it may be said

provisionally that the ancient potters of this region were unfamiliar

with it.

This apparently insignificant characteristic is

present, however, in all the pottery directly influenced by the culture

of the southwestern subceramic area. It occurs in pottery from the Gila

and the Salt River ruins, in the Hopi area, and along the Little

Colorado, including the Zu-i valley, and elsewhere. Until recorded from

the northeastern subceramic area, "the line of life" may be considered a

peculiarity of ceramics of the Gila subarea or of the pottery influenced

by its culture.

Among the restored food bowls from Spruce-tree House,

having characteristic symbols, may be mentioned that represented in

plate 16, d, d', which has on the interior surface a triangular

design with curved appendages to each angle. The triangular arrangement

of designs on the interior surface of food bowls is not uncommon in the

Mesa Verde pottery.

Another food bowl has two unusual designs on the

interior surface, as shown in plate 18, c, c'. The meaning of

this rare symbolism is unknown.

In plates 16-19 are represented some of the most

characteristic symbols on the restored pottery.

The outer surfaces of many food bowls are elaborately

decorated with designs as shown, while the rims in most cases are dotted.