|

Aztec Ruins

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 3: PEELING AWAY PREHISTORY (continued)

1916: EXPLORATORY SEASON

(continued)

In the formative period of Southwestern studies, there were no uniform guidelines for excavation, curation, or documentation procedures. Scientists working at Pecos, Puye, Mesa Verde, and in northeastern Arizona in 1916 were going about their explorations and recordation of data in their own ways with little or no consultation with each other regarding methodological or taxonomic standardization. Consequently, Morris had to rely on his personal previous experience in the Animas area to begin exposing Aztec Ruin. He devised his own phased excavation plan, cataloging system, and preservation techniques. The southeast corner of the site offered the easiest spot for training the crew. Its relatively low profile could be cut away with the least amount of time and effort. Later research indicated that it likely was a sector of the village where human occupation preceding the above-ground remains might have been identified had procedures been more refined. If such remains were present, they were destroyed or overlooked because of unfamiliarity with them.

Morris was aware of some of the weaknesses of his beginning efforts. He later commented, "The excavation at the south end of the east wing was done at the first season's explorations. Doubtless had a search been made of it, the last level of occupation might readily have been identified and used as a base plane. Instead the level followed was that of the field to the eastward." [9] The field, of course, had been plowed and was no longer representative of the aboriginal landscape. Even though the museum's instructions to Morris were to uncover the classic pueblo, the scientific staff expressed interest in a broader scope of inquiry than its man in the field accomplished. [10]

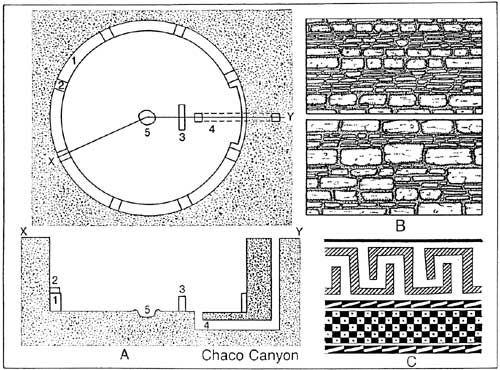

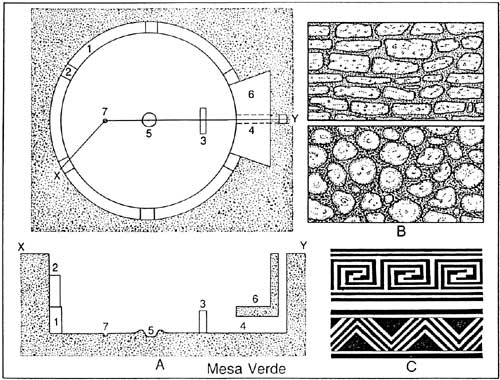

Earlier researchers pinpointed three major centers of prehistoric development on the Colorado Plateau sharing a widespread homogeneity of culture but with certain regional characteristics. Anasazi living in the Kayenta district of northeastern Arizona differed in some aspects of their material culture from those in the Mesa Verde domain. Both these groups evolved in ways that were compatible to, yet distinctive from, those of the Anasazi living in Chaco Canyon. All three branches shared an architectural mode for communal living, but construction methods and quality of workmanship differed (see Figures 3.2 and 3.3). Among lesser handicrafts, pottery was an especially useful diagnostic element of the material culture for students of the Anasazi past. It was the most abundant kind of portable artifact in most sites. All Anasazi used the same fundamental ceramic technologies, but some raw resources, vessel shapes, and decorative styles produced end products that became hallmarks of particular regions.

Figure 3.2. Chaco cultural traits present at Aztec Ruins. A) Plan and

profile of typical kiva:

1, bench; 2, low pilaster; 3, deflector; 4,

ventilator shaft; and 5, firepit. B) masonry types. C) pottery designs.

(After Lister and Lister, 1987: 89).

Figure 3.3. Mesa Verde cultural traits present at Aztec Ruins. A) Plan

and profile of typical kiva:

1, bench; 2, high pilaster; 3, deflector;

4, ventilator shaft; 5, firepit; 6, southern recess; and 7, sipapu. B)

masonry types. C) pottery designs.

(After Lister and Lister, 1987:

96).

Despite these relatively minor regional differences among the Anasazi as a whole, archeologists assumed that the three branches somehow had marched in unison through time. There was no means of dating Southwestern antiquities to verify or reject such a premise. Therefore, students of the Anasazi held the simplistic view that identifiable culture variances from enclave to enclave across the greater expanse of the Colorado Plateau provided the means for placing individual sites and their former inhabitants within an areal developmental framework that everywhere was at the same level of advancement at any given period. In 1916, the period with which most of the scientists were dealing was that culminating a cultural continuum of unknown duration. That was the period of Aztec Ruin.

Basing his judgment on these kinds of distinctions among groups of otherwise identical Anasazi, prior to excavation Morris felt that some observable elements at Aztec Ruin suggested either a local cultural hybridization between Chacoan and Mesa Verdian branches of the Anasazi or their contemporaneous sharing of the village. In either case, that sort of site utilization would have been unusual. To Morris, sandstone masonry remnants poking above the crust of the mounds and the configuration of the town plan were unquestionably of Chacoan derivation. However, the cobblestone southern enclosure was out of pattern for usual Chaco constructions. It also was not typically Mesa Verdian, but similar prehistoric houses in the vicinity contained what Morris believed to be Mesa Verdian trash. This was particularly true of recovered pottery. Morris concluded that most of it was of Mesa Verdian manufacture or strongly influenced by styles of that area. He observed a similar Mesa Verdian connection in litters of potsherds on the surface of the Aztec mounds. Only actual digging would resolve the questions.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

azru/adhi/adhi3-1.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006