MENU

Rocky Mountain

| Mission

66 Visitor Centers

Chapter 5 |

|

Designing the Headquarters: Four Important Points

Regardless of Wright's reputation for previous work in the area, Taliesin Associated Architects was known for carrying on his tradition of "Organic Architecture," the design of buildings closely related to the landscape. The firm's reputation for environmentally sensitive modern architecture attracted the attention of Mission 66 planners. When the commission was accepted, Tom Casey was assigned the position of project architect. Casey designed and supervised the building from concept through completion, as was the firm's standard practice. In an interview, Casey used "four points" to explain how Wright's philosophy influenced the design of the Headquarters. [26] First, the building had to appear part of the site and not merely sit upon the land. Second, methods of structural manipulation were employed to destroy the traditional "box" characteristic of so much American architecture. Third, materials would be chosen for the effects of weathering over time so that they might reveal their true nature. And finally, if the building were to represent American architecture, it must somehow symbolize democracy. Like Le Corbusier's famous "five points," these four points were intended to simplify Wright's complex and continually changing design philosophy into terms the public could understand. Taliesin developed this summary of Wright's teachings in the early 1980s, when the firm was preparing a traveling exhibit of his work called In the Realm of Ideas. Although Wright himself never distilled his philosophy in this way, this concise formula helps to explain certain aspects of the headquarters design.

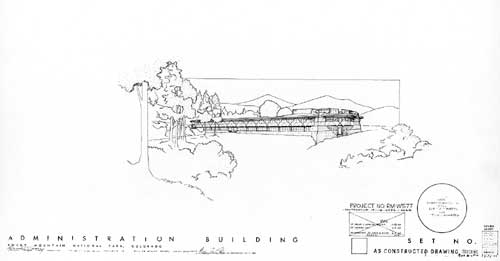

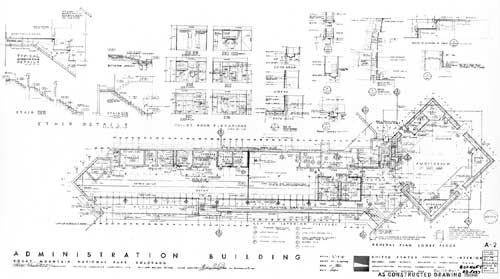

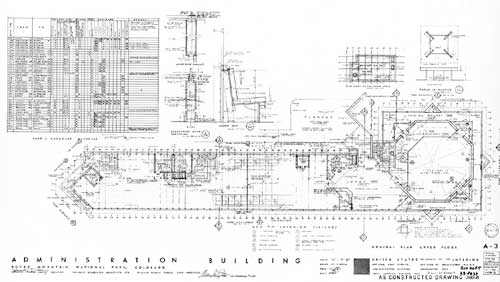

Figure 55. This sketch of the front elevation of the Headquarters served as a cover sheet for the set of "as constructed" drawings completed in March 1967.

(Courtesy National Park Service Technical Information Center, Denver Service Center.)In plan, the building Casey designed resembles several of the early Park Service schemes: it consists of a long corridor of administrative offices attached to a larger room housing featured visitor services. The box is "burst" by a triangular conclusion to the administration wing and the 45-degree rotation of the auditorium, which results in an unusual lobby space. The building is sited "in the land" so that the transition from the upper to the lower floor is hardly noticeable. And yet employees entering from the rear perceive the building as two stories. This level change and the organization of spaces effectively separates visitors from park staff without requiring prohibitive signs or resulting in confusion and unnecessary traffic in the staff area. [27] The transition from inside to outside is also emphasized using a variety of Wrightian methods. The entrance to the main lobby is low and dark, but opens into a lobby with a higher ceiling. Lights hidden behind the steel facia and natural lighting from a clerestory window on the west side enhance the contrast from low to high, dark to bright. These effects are also apparent in the office corridors, where oppressively low halls lead to offices with high ceilings and clerestory windows.

The third "point" of design, the nature of materials, is both the most obvious and the most complex. The disoriented visitor is likely to stumble inside without paying much attention to the variety and color of stones, their contrast with the bare concrete, or the pink paint under the eaves that matches mortar and sidewalk. But even the most oblivious might notice the unusual Cor-ten steel framework enveloping the second story of the building. The dynamic pattern wrapping around the building is built up in several layers, with thin steel sheets welded onto the thicker tubes that form the framework. The resulting abstract design, a series of rigid triangles said to have been derived from Indian rock art, reappears throughout the building—as interior ornament, in the angles of rooms, and other unexpected places. Steel trim is also a feature along the roof of the building, where it serves as a cornice and is embossed with a decorative pattern. This design is repeated in the pressed metal panels around the auditorium. If the roughness and redness of the stones is intended to blend with the surroundings, the steel ornament seems a deliberate effort to fight this tendency. Even the steel's deep reddish color fails to "naturalize" this sharp, industrial material. Whether the building is successful in its effort to satisfy the fourth point—to qualify as "democratic" architecture—is purely subjective. That the Headquarters was designed by architects, and intended to convey abstract meaning, however, is obvious.

In a general way, "the four points" can be observed in any Wrightian design. For the purposes of this study, however, comparative analysis is limited to the examples that the apprentices knew best: Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona, and Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin. A quick glance at Taliesin West establishes its striking resemblance to the Headquarters building—the low profile, stone aggregate in cast concrete, and exposed structural system. The buildings draw attention to the landscape, both through siting and choice of material. Wright described Taliesin West as a ship, with its "concrete prow" facing south overlooking Paradise Valley and the Camelback Mountains. [28] The Headquarters also has a ship-like form, and during construction, the auditorium end was referred to as "the east prow of the Monitor." [29] Taliesin is surrounded by low walls and planters for cactus; the Headquarters uses similar low walls to define entrances and areas for plantings. A separate theater building, known as the kiva, stands on one corner of the Taliesin complex. Not coincidentally, the amphitheater at Rocky Mountain was said to resemble a ceremonial kiva, though probably more in its association with the Taliesin building than an authentic Southwestern Indian dwelling. The symbol for Taliesin Fellowship, an interlocking square spiral, was an adaptation of a prehistoric pictograph discovered near the Ocatilla camp. [30] According to Wright, "inspiration for Taliesin West came from the same source as the early American primitives and there are certain resemblances, but not influences." [31] The ceiling of the drafting room at Taliesin in Spring Green is decorated with a pattern of jagged triangles protruding from wood trusses, much like the triangular ornament featured throughout the Headquarters. The ornament used in the Headquarters may have had its closest antecedents in the Fellowship's own design vocabulary.

|

History | Links to the Past | National Park Service | Search | Contact |

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/allaback/vc5b.htm

![]()