|

ACADIA

The Sieur de Monts National Monument As Commemorating Acadia and Early French Influences of Race and Settlement in the United States Sieur de Monts Publications IX |

|

SIEUR DE MONTS PUBLICATIONS

IX

The Sieur de Monts National Monument

As Commemorating

Acadia and Early French Influences of Race and

Settlement in the United States

GEORGE B. DORR

The Sieur de Monts National Monument combines in a remarkable way three separate aspects: It is an extraordinary Nature Monument, as such are termed abroad, fitted to exhibit and preserve its regional life in the widest range a single area can, and to set forth its region's geologic history; it is a great Recreation Area, a park in the true popular sense, capable in the highest degree of drawing; city-wearied men and sending them away refreshed much stimulated and it is a Historic Monument of singularly impressive character whose ancient granite heights, sculptured in bold relief by ice and sea, commemorate as they look out across the stormy wilderness of the North Atlantic the men who sailed across that wilderness in early days from ports of western France to settle on the Acadian shores or fish in the Acadian seas.

|

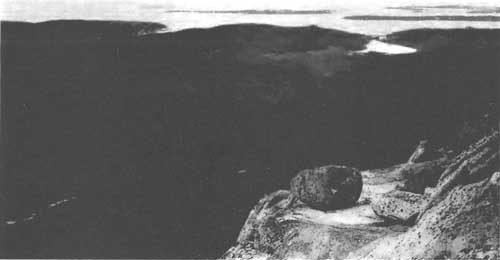

| The waters of Champlain's approach from the "Sainete Croix" colony to Frenchmans Bay, and the "Monts deserts" he saw |

The first commissions that resulted in permanent settlement on the American continent to the north of Florida were issued by Henry of Navarre, Henry IV of France, in December, 1603, to Pierre du Guast, Sieur de Monts and Governor of Pons, a Huguenot of noble family who had served the King faithfully through the recent wars and stood high in his esteem.

De Monts, then not over thirty years of age and in his prime, was a native of Saintonge, a district facing on the Bay of Biscay between La Vendée and Bordeaux, which was the home of Champlain also who accompanied him to the Acadian shores. Born of one of the most ancient families of France, that had served the Crown for centuries with credit and distinction, all accounts agree in praise of him as a brave and gallant gentleman. Champlain who later wrote the history of the enterprise speaks of him ever in terms of warm regard, and states that the King had "great confidence in him for his fidelity, as he ever showed, even to his death—," while the Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier de Charlevoix, writing over a century later, described him, though a Huguenot, as "a most honorable man of upright views and zealous for the State, who had every quality necessary for success in the enterprise committed to his charge." Court intrigues and powerful trading influences seeking to control the valuable fur-trade rights which had been granted him and his associates to meet the expense of new colonial establishments on a yet savage coast, forested to the water's edge, wrested at length his charter from him, to be restored again, then lost again, till the assassination of Henry IV, by a fanatic, on the 14th of May, 1610, involved in a common ruin de Monts and the best interests of France.

The Jesuits took up in turn the work de Monts had left, establishing a colony in 1613 at Mount Desert, the first land touched on by Champlain within the limits of the United States, when, in September, 1604, he sailed out from its future boundary at the mouth of the St. Croix, where de Monts was establishing his first colony, to explore the neighboring coast. For a century after, till the peace of Utrecht, France continued to hold the land it called Acadia, a name which included until then the magnificently harbored coast of eastern Maine as well as Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

Had France, moved by the spirit of Henry IV and de Monts, made some present sacrifice to consolidate what their and other early enterprise had won instead of plunging again upon the death of Henry into factional politics and religious strife, she probably and not Anglo-Saxon nations would have controlled the larger destinies and development of this continent.

It was a time of new beginnings when mighty rivers of future history were gathering their first waters and establishing their yet doubtful course. France, through the enterprise and adventurous spirit of the early mariners and nobles on her western coasts, fronting the Atlantic, won the first advantage in the occupation of the new continent discovered on its opposite shores, she lost her opportunity through the triumph of reactionary politics and selfish privilege which culminated in the French Revolution's fearful travail after thwarting for generations the best energies of the nation and destroying largely or sending into exile her best blood.

|

| The coast that Champlain skirted when he left the Island, guided by Indians, to ascend the Penobscot River |

The French Dominion

FRANCIS PARKMAN

The French dominion is a memory of the past; and when we evoke its departed shades, they rise upon us from their graves in strange, romantic guise. Again their ghostly camp-fires seem to burn, and the fitful light is cast around on lord and vassal and black-robed priest, mingled with wild forms of savage warriors, knit in chose fellowship on the same stern errand. A boundless vision grows upon us; an untamed continent; vast wastes of forest verdure; mountains silent in primeval sleep; river, lake, and glimmering pool; wilderness oceans mingling with the sky. Such was the domain which France conquered for Civilization. Plumed helmets gleamed in the shade of its forests, priestly vestments in its dens and fastnesses of ancienit barbarism. Men steeped in antique learning, pale with the close breath of the cloister, here spent the noon and evening of their lives, ruled savage hordes with a mild, parental sway, and stood serene before the direst shapes of death. Men of courtly nurture, heirs to the polish of a far-reaching ancestry, here, with their dauntless hardihood, put to shame the boldest sons of toil.

It is a memorable but half-forgotten chapter in the book of human life that can be rightly read only by widely scattered lights.

W. F. GANONG

Striking description of the landing of de Monts and Champlain to lay the first foundations of Acadia, taken from address delivered at the Ter-Centennial Celebration held at St. Croix Island on June 25th, 1904, in which France, England and the Uniited States were all officially represented.

Three centuries ago today all the northern part of America was one vast wilderness mind all its mighty sweep of forest and plain a solitude, save only where the little groups of Indian lodges clung to the shores of its lonely rivers.

In the year 1604 over a century had already elapsed since Columbus had found the New World, and since Cabot had explored its northeastern coast for England and marked it for the empire of the Anglo-Saxon. Over three-quarters of a century had passed since Verrazano had explored the same coast for France; and nearly as long since Cartier had carried the fleu-de-lys up the St. Lawrence, having the foundation for the French dominion in America. Both nations had thus acquired claims to this continent, but neither had obtained any foothold upon it. Both, indeed, had attempted settlement, the English in Newfoundland and Virginia, and the French at Quebec amid Tadoussac; but both had failed. Upon the whole continent only the Spaniard had succeeded, for he had planted a small settlement in Florida and others around the Gulf of Mexico; elsewhere, and everywhere to the northward, there was only wilderness.

Such was the state of North America, when, on a fair midsummer day, just three centuries ago, a tiny vessel came sailing along the lonely Fundy coast from the eastward and turned her prow to the river on whose historic banks we are now standing. She was a tiny craft that thus appeared out of the unknown, for she was no larger than the fishing sloops we know so well in our Quoddy waters today. She carried ahout a dozen men, of whom two bore the unmistakable stamp of leadership.

One was a prominent gentleman of France, lofty in spirit, devoted in purpose, trusted of his King, the commander of the company, Sieur de Monts. The other was one of the great men whom France has given to the world, a remarkable combination of dreamer and man of swift and wise action. The intentness of his gaze as one new feature after another unfolds itself along the coast, and his constant use of compass and pencil, shows him to be the geographer and chronicler of the expedition. He was the first cartographer and historian of Acadia. Samuel de Chaplain.

But the little vessel is coming nearer; she reaches our beautiful Passamaquoddy islands; she winds her cautious and curious way among them; she crosses the spacious bay; she enters our noble river; she sails up the hill-bordered valley; she reaches the island where today we placed our memorial, then unbroken forest; her sails are furled; the leaders step ashore and, with the air of men who have ended a weary search, declare that it is good and that here they will plant the capital of the New World.

Whence came this little vessel? What carried she that we should here assemble three centuries later, to celebrate her coining?

She was the herald of the permanent occupation of the northern part of America by Europeans. From the day the keel of her small boat grated on the beach of St. Croix Island, this continent has never been without a population of those races which have made the history of the principal part of America,—the French and the English. We celebrate today not only an event of great human interest, but one of the momentous circumstances of history, the actual first step of North America from barbarism over the threshold of civilization, and the first stage in the expansion of two of the most virile races of Europe into the wonderful New World.

NOTE BY EDITOR.—/De Monts had left his well-equipped and furnished larger vessel in safe moorings at St. Mary's Bay, upon the Nova Scotia coast—opposite Mount Desert Island, at the eastern entrance to the Bay of Fundy—while he and Champlain searched out, in the little barque of a few tons described, a site upon the unknown shore beyond for their first colony.

Acadia at the End of the Seventeenth Century

FRANCIS PARKMAN

Amid domestic strife, the war of France with England and the Iroquois went on. Each division of the war was distinct from the rest, and each had a character of its own. As the contest for the West was wholly with New York and her Iroquois allies, so the contest for Acadia was wholly with the "Bostonnais," or people of New England.

Acadia, as the French at this time understood the name, included Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and the greater part of Maine. The river Kenebec, which they looked on as the true dividing line between their possessions and New England, they regarded with the most watchful jealousy. Its headwaters approached those of the Canadian river Chaudière, the mouth of which is near Quebec; and by ascending the former stream and crossing to the headwaters of the latter through an intricacy of forests, hills, ponds and marshes, it was possible for a small band of hardy men to reach the Canadian capital—as was done long after by the followers of Benedict Arnold. Hence, it was thought a matter of the last importance to control the river.

Since the wars of D'Aunay and La Tour, this wilderness had been a scene of unceasing strife; for the English drew their eastern boundary at the St. Croix, and the claims of the rival nationalities overlapped each other.

Along the lonely coasts one might have sailed for days and seen no human form. At Canseau, at the eastern end of Nova Scotia, there was a fishing-station and a fort; Chibucton, now Halifax, was a solitude; at La Ilêve there were a few fishermen; and thence, as you doubled the rocks of Cape Sable, the ancient haunt of La Tour, you would have seen four French settlers and an unlimited number of seals and sea-fowl. Ranging the shore by St. Mary's Bay and entering the Strait of Annapolis Basin, you would have found the fort and settlement of Port Royal, the chief place of all Acadia. It stood at the head of the basin, where de Monts had planted his settlement eighty or one hundred years before. At the head of the Bay of Fundy were two other settlements, Beaubassin—the Beautiful Basin—and Les Mines—the Place of Mines, comparatively stable and populous. At the mouth of the St. John were the abandoned ruins of La Tour's old fort; while at some distance up the river stood the small wooden fort of Jemsec, within a few intervening clearings. Still sailing westward, passing Mount Desert—another scenic of ancient settlement—and entering Penobscot Bay, you would have found the Baron de Saint-Castin, with his Indian household, at Pentegoet, where the town of Castine now stands. All Acadia was comprised in these various stations, more or less permanent, together with one or two small posts on the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the huts of an errant population of fishermen and fur-traders.

Rude as it then was, Acadia had charms—and has them still—in its wilderness of woods and its wilderness of waves, the rocky ramparts that guard its coasts; its deep, still bays and foaming headland; the towering cliffs of Grand Menan; the innumerable islands that cluster about Penobscot Bay; and the romantic highlands of Mount Desert, down whose gorges the sea-fog rolls like an invading host while the spires of firs and spruces pierce the surging vapors like lances in the smoke of battle. Leaving Pentegoet and sailing westward all day along a solitude of woods, one might reach the English outpost of Pamaquid, and thence, still sailing on, might anchor at evening off Casco Bay, and see in the glowing west the distant peaks of the White Mountains.

Inland, Acadia was all forest, as vast tracts of it are primeval forest still. Here roamed the Abenakis with their kindred tribes, a race wild as their haunts. Their villages were on the waters of the Androscoggin, the Saco, the Kennebec, the Penobscot, the St. Croix, and the St. John; here in spring they planted their corn, beans, and pumpkins, and then, leaving them to grow, went down to the sea in their birch-canoes. They returned towards the end of summer, gathered their harvest, and went again to the sea, where they lived in abundance on ducks, geese, and other water-fowl. During the winter, most of the women, children, and old men remained in the villages; while the hunters ranged the forest in chase of moose, deer, caribou, beavers, and bears.

Their summer stay at the seashore was perhaps the most pleasant, and certainly the most picturesque, part of their lives. Bivouacked by one of the innumerable coves and inlets that indent these coasts, they passed their days in that alternation of indolence and action which is a second nature to the Indian. Here in wet weather, while the torpid water was dimpled with rain-drops and the upturned canoes lay idle on the pebbles, the listless warrior smoked his pipe under his roof of bark; or launched his slender craft at the dawn of the July day, when shores and islands were painted in shadow against the rosy east, and forests, dusky and cool, lay waiting for the sunrise. The women gathered raspberries or whortleberries in the open places of the woods, or clams and oysters in the sands and shallows, adding their shells to the shell-heaps that have accumulated for ages along these shores. The men fished, speared porpoises, or shot seals. A priest was often in the camp watching over his flock, and saying mass every day in his chapel of bark. There was no lack of altar candles, made by mixing tallow with the wax of the bayberry, which abounded among the rocky hills and was gathered in profusion by the squaws and children.

Some of the French were as lawless as their Indian friends. Nothing is more strange than the incongruous mixture of the forms of feudalism with the independence of the Acadian woods. The only settled agricultural population was at Port Royal, Beaubassin, and the Basin of Minas. The rest were fishermen, fur-traders, or rovers of the forest. Repeated orders came from the court to open a communication with Quebec, and even to establish a line of military posts through the intervening wilderness; but the distance and the natural difficulties of the country proved unsurmountable obstacles.

If communication with Quebec was difficult, that with Boston was easy; and thus Acadia became largely dependent on its New England neighbors, who, says an Acadian officer, "are mostly fugitives from England, guilty of the death of their late King, and accused of conspiracy against their present sovereign; others of them are priates; and they are all united in a sort of independent republic." Their relations with the Acadians were of a mixed sort. They continually encroached on Acadian fishing-grounds, and we hear at one time of a hundred of their vessels thus engaged. They often landed and traded with the Indians along the coast. Meneval, the governor, complained bitterly of their arrogance. Sometimes, it is said, they pretended to be foreign pirates, and plundered vessels and settlements, while the aggrieved parties could get no redress at Boston. They also carried on a regular trade at Port Royal and Les Mines or Grand Pré, where many of the inhabitants regarded them with a degree of favor which gave great umbrage to the military authorities, who, nevertheless, are themselves accused of seeking their own profit by dealings with the heretics. The settlers caught from the "Bostonnais" what their governor stigmatizes as English and parliamentary ideas, the chief effect of which was to make them restive under his rule. The Church, moreover, was less successful in excluding heresy from Acadia than from Canada. A number of Huguenots established themselves at Port Royal, and formed sympathetic relations with the Boston Puritans. The bishop at Quebec was much alarmed. "This is dangerous," he writes; "I pray your Majesty to put an end to these disorders."

"Men know little of the consequences of their actions. It was the Stuart policy of religious intolerance at home and of allowing colonies as safety valves for dissent which laid the sure foundation of the future United States."

—Cambridge Modern History.

After the Peace of Utrecht

FRANCIS PARKMAN

"Along the borders of the sea an adverse power was strengthening with slow but steadfast growth. By name, local position and character, one community stands forth as the conspicuous representative of this antagonism—Liberty and Absolutism, New England and New France."

After the Peace of Utrecht, in 1713, the contest between France and England in America divided itself into three parts,—the Acadian contest; the contest for northern New England; the contest for the West. Nothing is more striking than the contrast in the conduct and methods of the rival claimants to this wild but magnificent domain. Each was strong in its own qualities, and utterly wanting in the qualities that marked his opponent.

On maps of British America in the earlier part of the eighteenth century, one sees the eastern shore, from Maine to Georgia, garnished with ten or twelve colored patches, defined, more or less distinctly, by dividing-lines which in some cases are prolonged westward till they touch the Missisippi, or even cross it and stretch on indefinitely. These patches are the British provinces, and the westward prolongation of their boundary lines represents their several claims to vast interior tracts, founded on ancient grants but not made good by occupation, or vindicated by any exertion of power.

These English communities took little thought of the region beyond the Alleghanies. Each lived a life of its own, shut within its own limits, not dreaming of a future collective greatness to which the possession of the West would be a necessary condition. No conscious community of aims and interests held them together, nor was there any authority capable of uniting their forces and turning them to a common object. Each province remained in jealous isolation, busied with its own work, growing in strength, in the capacity of self-rule and the spirit of independence, and stubbornly resisting all exercise of authority from without. If the English-speaking population flowed westward, it was in obedience to natural laws, for the King did not aid the movement, the royal governors had no authority to do so, and the colonial assemblies were too much engrossed with immediate local interests. The power of these colonies was that of a rising flood slowly invading by the unconscious force of growing volume.

In the French colonies all was different. Here the representatives of the Crown were men bred in an atmosphere of broad ambition and far-reaching enterprise. Achievement was demanded of them. They recognized the greatness of the prize, studied the strong and weak points of their rivals, and with a cautious forecast and a daring energy set themselves to the task of defeating them.

If the English colonies were comparatively strong in numbers their numbers could not be brought into action; while if the French forces were small, they were vigorously commanded, and always ready at a word. It was union confronting division, energy confronting apathy, military centralization opposed to industrial democracy; and, for a time, the advantage was all on one sidle.

The demands of the French were sufficently comprehensive. They regretted their enforced concessions at the Treaty of Utrecht, and, in spite of that compact, maintained that, with a few local exceptions along the Atlantic Shore, the whole North American continent, except Mexico, was theirs of right; while their opponents seemed neither to understand the situation, nor to recognize the greatness of the stakes at issue.

"The Articles in the Treaty of Utrecht which dealt with cessions made by France to Great Britain in the New World are justly regarded as the real beginnings of the expansion of the British Colonial Empire in America—hence, also, of the United States and its democracy. It was a notable event accordingly in the view-point of World History when, by the Treaty's terms, Acadia—save Cape Breton Island—was assigned to England."

—Cambridge Modern History.

| <<< Previous |

sieur_de_monts/9/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 03-Dec-2009