![]()

Five Views: An Ethnic Historic Site Survey for California

MENU

Introduction

Mexican War

Post-Conquest

1900-1940

World War II

Chicano Movement

Future

Historic Sites

Selected References

A History of Mexican Americans in California:

HISTORIC SITES

South Colton

Colton, San Bernardino County

South Colton comprises 1.36 square miles of the City of Colton in San Bernardino County. Surrounded by railroad tracks, it includes the area east from Rancho to 12th streets, south to Fogy, and north to the San Bernardino Freeway. The houses are deteriorating; much of the small commercial section is closed; and the streets are in disrepair.

With a population of 3,350, 85 percent of whom are Mexicanos, South Colton's significance is that all of the trends in Chicano working-class history are present in this small community. Threatened now by urban renewal and private development, South Colton is one of the very few barrios in California that offers the opportunity for preserving and maintaining the integrity of a community that clearly reflects the entire scope of Chicano history.

The town of Colton was created by promoters of the Southern Pacific Railroad who wanted to divert the traffic and prosperity synonymous with railroads away from the neighboring city of San Bernardino. These promoters intended to make Colton the railroad center of Southern California. The Chicano barrio, the southside of Colton, is also synonymous with railroads and with the Southern Pacific, which brought in Mexican labor in the 1890s to build, repair, and maintain the rail lines. Begun as a railroad labor camp adjacent to the railroad tracks, South Colton developed in the same way as many Chicano barrios and colonias throughout the southwest and the midwest. In most cases, Mexican labor came in with the railroads and established lasting communities from what were originally railroad labor camps. These communities were founded next to the tracks because that was often marginal land, affordable and close to work, and because de facto segregation existed. In Colton, th e Chicano community established itself on an open section of land southeast of the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks where most of the Mexicanos worked.

The new Mexicano community developing close to the tracks was directly adjacent to a well-established Spanish-speaking community made up of descendants of the original New Mexican/Genizaro settlers of San Salvador. These settlers, from Abiqiui, New Mexico, had come to the river-bottom area near South Colton in 1843, at the behest of Californio rancheros who wanted families to colonize the outer limits of their lands and protect their property from Indian attack, thieves, and marauders. In exchange, the New Mexican pioneers, led by Hipolito Espinosa and Lorenzo Trujillo, received land on which to settle, farm, and establish their own communities. In 1913, when the Church of San Salvador was built in South Colton, the two Spanish-speaking communities merged. The original San Salvador Church was built in Agua Mansa by the community in 1853. It had, however, been abandoned in the 1890s, and was subsequently reconstructed in South Colton when barrio residents petitioned the Arch diocese for their own church. San Salvador Church, central to the religious, social, and political life of South Colton, still sits on the corner of 7th and M streets where it was built in 1913.

Colton, San Bernardino County

As the town of Colton continued to grow and prosper, the Chicano barrio also grew, through natural increase as well as continued immigration. By 1905, South Colton had 500 residents and was called "Little Mexico" and "Choloville" by the Anglo residents of Colton. South Colton developed according to the economic, social, and political realities of the Mexicanos and Chicanos who lived and worked there. Little by little, Mexicanos bought small lots and designed and built their own homes using materials they could afford, and with the help of family and friends. Thus, the homes in South Colton are primarily small, wooden frame structures, many of which started out as shacks constructed of discarded lumber and corrugated metal. Many are of an elongated design, with one room after another added as families grew. In most cases, there is a small garden either to the side or at the back of the house, and the lot is made attractive by the addition of numerous plants in brilliantly colored pots. Many of the lots also have cactus and other succulents planted near or around the house. The design of the homes, the material used to construct them, and the use of the exterior space reflects not only the economic conditions and space needs of the Chicanos in South Colton, but also their aesthetic and cultural sensibilities. In short, the Mexicanos who created this community gave it the aesthetic form and texture they were familiar with in Mexico. They re-created a Mexican environment.

The economic, social, and political conditions, and the Chicano response to them in South Colton, are further revealed in the history of the community. In response to poverty, racism, and exclusion from socio-political institutions in the town of Colton, Chicanos in the barrio created their own institutions to educate their young, provide medical aid, and offer economic assistance. They also formed a labor union. By 1910, South Colton had an underground Spanish-language academy, where barrio youngsters were instructed in their community's language, values, and history after the regular school day and on Saturday mornings. In 1913, community organizations in South Colton included a mutualista group (mutual aid society), a Comite de Fiestas Patrioticas (committee for celebrating Mexican national holidays), and a women's Cruz Azul (Blue Cross) society. The mutualistas helped each other with burial and other expenses when work-related and other calamities occurred. The Cruz Azul members visited the sick and helped families when illness struck in the barrio. Celebrations of Mexico's national holidays, particularly the 16th of September and Cinco de Mayo, were organized by the Comite de Fiestas Patrioticas.

In 1917, Chicano workers organized the Trabajadores Unidos union and led a successful strike against the Portland Cement Company, one of Colton's major industries and its largest employer. The two-month strike was in protest of a cut in Mexicanos' wages by the cement company, whose rationale for the wage cut was that Mexicans were making too much money. Anglo workers employed at the cement company did not have their wages cut. Trabajadores Unidos won the strike; the company rescinded the wage cut. Subsequently, the union opened a cooperative grocery store which they called "La Union."

The period from World War I to the Great Depression saw some growth, but not parallel growth, of Colton's two communities. South Colton did not receive its share of municipal funds for municipal services, or educational and recreation facilities. Streets in South Colton remained unpaved; sewage services were nonexistent. Chicano youngsters were segregated in a Mexican grade school with inadequate facilities and insufficient teachers, and were not welcome in the town's one high school in Colton proper. The city's swimming pool was segregated; Mexicanos could swim only on the day before the water was to be changed. The town's theater was also segregated. The two communities remained segregated, and except for work and some shopping, Chicanos and Anglos seldom interacted.

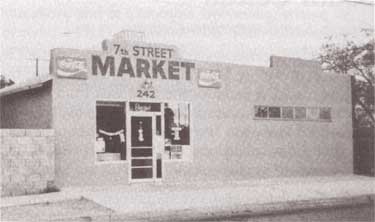

In South Colton, Chicano-owned businesses sprang up to serve the Chicano community. A number of small businesses, including bakeries, groceries, restaurants, pool halls, taverns, clothing, and butcher shops, met most of the shopping needs of the community. While most of these stores are now closed, a few still exist, such as the Seventh Street Market, still operated by the original owners, and Martinez's Bakery, now a small grocery store run by the daughter of the original owner. The significance of these stores cannot be overestimated. They not only provided necessary provisions for a community that had restricted access to stores in Colton proper, but they did so in the language, mannerisms, and customs expressing the economic and cultural values of a working-class Mexican community. Even their decor, which included notices of community events, an altar dedicated to a special saint, or the owner's patron saint sitting in a special corner, reaffirmed the cultural identify of the community. Forced into segregation by economic circumstance and racial discrimination, the Chicano community placed its indelible stamp on South Colton.

The community's social functions, including quincianeras, baptisms, weddings, dances, Fiestas Patrioticas, and other social activities, were held in either the Parish Hall or a dance hall built in South Colton. The social life of the community revolved around these two halls, which were always decorated with banderitas, brilliantly colored crepe paper, and other ornaments reflecting the aesthetic sensibilities of the community. Significant, too, is the fact that these activities involved the entire family. Grandparents, parents, young marrieds, teenagers, and infants all attended the dances, which often attracted big-name Mexicano and Chicano bands and conjuntos from Los Angeles. For men in particular, local pool halls and taverns were major centers of social activity — a place to relax, have a beer, see friends, and talk over situations regarding family, work, and making ends meet.

To meet the community's entertainment needs and interests, as well as to counter the racism represented by the segregated Anglo-owned theater in Colton, two Chicano theaters showing Spanish-language films opened in South Colton. El Tivoli on 7th and O Streets and El Teatro Hidalgo not only showed films, they were also centers for community activity and Spanish-language theatrical presentations, including those of the traveling Circo Escalante from Los Angeles, and tandas de variedad. The latter activity usually consisted of local residents displaying their talents to each other. Cecilia Martinez Williams, born and raised in South Colton and now owner of Martinez's Bakery, fondly recalled performing at the Tivoli as a child, and stated that children's performances were a regular part of the activities at the Tivoli. Only a cement slab remains of the Tivoli now.

To ensure that Chicano youngsters had a place to swim on a daily basis and that the community had a recreational center, Juan Caldera, owner of Caldera's Carniceria (butcher shop), built a stadium complex in South Colton in 1922. Calling it the International Stadium, Caldera built a swimming pool, a baseball diamond, and bleachers. Chicano baseball teams from all over Southern California came to South Colton to compete in an informal and unofficial, but very active, Chicano baseball league. Of the stadium and swimming pool, very little remains — a cement foundation and a dusty, overgrown field are the only reminders of the structures around which the community's recreational life revolved in the years before the Depression of the 1930s.

Repatriation and deportation of Mexicanos during the Great Depression not only served to depopulate South Colton, but also effectively destroyed the developing economic and social stability of the barrio. Most of the stores were closed. Many of the residents, including Caldera, later returned, but they had lost their property and any savings accumulated before repatriation or deportation. South Colton never recovered from the effects of the repatriation/deportation program.

During the Second World War, young people left the barrio as the community sent its young men to war. After the war, they moved to urban centers where economic and educational opportunities appeared more accessible. Those who stayed in South Colton during and after the war, however, began to organize politically and challenge the Anglo establishment. Excessive force used by Colton police in what has been called the "Colton Zoot Suit Riot" was soundly condemned by Chicanos. They saw it as part of the attack against Mexicanos that occurred in Los Angeles in 1943, when Anglo sailors and marines attacked Mexican and Black youngsters wearing "drapes," stripped and beat them, and then watched the police arrest them. Chicanos in South Colton launched protests against the police and demanded better municipal services from City Hall, desegregation of the schools, and a voice in local government. In the 1950s, they elected a Chicano councilman.

Organization and political activity continued in the 1960s as residents of South Colton joined the Chicano movement in the struggle for political participation and civil rights. In 1979, Colton elected a Chicano mayor and two Chicanos on the City Council, as well as a Chicano school board member.

Though political gains have been won, South Colton remains economically depressed, and the Chicano barrio is in danger of succumbing to urban renewal. The barrio now sits on prime industrial property, and private developers are anxious to buy out low-income property owners and make the area into an industrial park. At this time, although many of the original families still reside there, the population is increasingly composed of recent arrivals from Mexico. They, like the original inhabitants, have come in as unskilled labor in non-union industries; they receive low wages, and have few economic benefits or securities. These newer residents come to a community that is essentially Mexicano in language, values, and customs. They contribute mightily to its linguistic, social, cultural, and historical continuity as a Chicano community.

From the original Bandini and Lugo land grants to the pioneer settlements of New Mexican-Genizaros at San Salvador, the influx of Mexican railroad labor, segregation of the two communities, and development of a Chicano working class community in South Colton, the Chicano historical experience is woven into the structures and the economic, linguistic, social, and cultural fabric of this small, self-contained Chicano barrio.

Colton, San Bernardino County

NEXT> Spanishtown Site

Last Modified: Wed, Nov 17 2004 10:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/5views/5views5h84.htm

![]()

Top

Top