Madison, Indiana

Industrial Madison

|

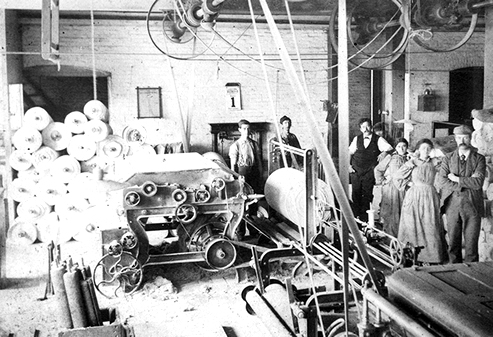

The Eagle Cotton Mill rolling room, c. 1890.

|

Madison suffered from the drawback of a sole-source economy, when the pork packing industry declined through the 1850s. The railroad rerouted hogs to other slaughterhouses throughout the Midwest, leaving Madison in an industrial slump. The cycle of success and failure marked the city for the rest of the 19th century. The Civil War stimulated Madison’s economy as foundries and shipbuilders worked to supply the Union Army. Following a decade of economic stability, the economic panics of the 1870s again plagued Madison’s development. A surge in industrial interest during the early 1880s created an economic bubble responsible for many large manufacturing facilities built along the riverfront including the massive Eagle Cotton Mill, the Schofield Woolen Mill, Johnson Starch Works, and Trow’s Mill--one of the largest flour mills in the State of Indiana.

During this time, Madison became the saddletree capital of the Midwest. (Saddletrees are the carved, wooden frames that make the foundation of saddles.) Attracted by southern Indiana’s hardwood forests and the ease of shipping finished products along the Ohio River, German Americans settled in Madison and fostered the industry along Walnut Street and Crooked Creek north of downtown. By 1879, Madison had 12 saddletree factories employing around 125 men and producing over 150,000 saddletrees a year. The Ben Schroeder Saddletree Factory, which began during the industry’s peak, stayed in production until the 1970s. The factory produced wooden saddletrees, work gloves, clothespins, and even lawn furniture during the company’s 94 years.

|

The 1937 Flood wiped out most of the factories and warehouses located along |

Prosperity was short-lived, however, with Madison’s population dropping from 10,709 in 1880 to 6,530 in 1930, and its industrial output dipping to pre-Civil War lows. The stagnation resulted in the preservation of many 19th century manufacturing sites that may have been demolished for larger factories or updated if business had continued to boom. Need for larger, more modern facilities never threatened the historic manufactories as Madison’s industrial riverfront declined. Examples of surviving small-scale buildings include 116 and 120 Elm Street, which were originally constructed as a carriage house and stables. With foundries and mills in the vicinity, these buildings could have easily been lost. Instead, 120 Elm Street was converted into the Trow Flour Mill Cooperage and then served as a tobacco prizing house from the 1920s into the 1960s.

The industrial sector’s proximity to Madison’s waterfront contributed to its 19th century success and helped facilitate shipping, but its location ultimately led to the demise of many industrial buildings. Larger-scale manufacturers located in Madison struggled to stay in business during the Great Depression. Many massive 1880s buildings once used as warehouses and factories sat empty until the Ohio River flooded Madison in January 1937. Recorded as the worst Ohio River Valley flood in history, water from the river rose to 72 feet, completely covering Vaughn Drive. Crooked Creek’s level rose as well, turning Madison into a peninsula and West Madison into an island connected to the rest of town by only a bridge. The massive destruction downtown claimed most of the industrial buildings, which were either destroyed by floodwaters or severely compromised and later demolished. The flood changed Madison’s use of the riverfront. Property formerly dedicated to factories was converted to recreational areas. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) era Crystal Beach Swimming Pool and Bath House, for example, stands on the former site of the Trow Flour Mill at the corner of Vaughn Drive and Elm Street.