Using Global Positioning System (GPS) and Geographic Information System (GIS) Tools in the Rehabilitation of Cultural Landscapes:

Gettysburg’s Codori Farm Lane Project.

by

Curt Musselman

Cartographer (GIS Coordinator)

National Park Service

Gettysburg National Military Park

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, USA

ABSTRACT:

Restoration of the historic Codori Farm Lane was one of the first cultural landscape rehabilitation projects undertaken following the approval in 1999 of Gettysburg National Military Park’s new General Management Plan (GMP). In order to carry out the GMP, detailed studies are conducted for the specific parts of the battlefield that will be undergoing treatment. The park’s GIS has played a key role in the planning studies and in the analysis of landscape features. In addition to documenting existing features from various historic eras, GPS and GIS tools have been used to determine the placement of the features being restored. This project included scanning historic base maps in the Library of Congress collection, gathering ground control points using GPS, rectifying the historic maps using ArcINFO to match more accurate maps of existing conditions, and navigating to the historic fence line locations using a Trimble ProXR GPS unit with real time differential correction capabilities. This project demonstrates how GPS and GIS tools are being used in the NPS on an operational basis in the cultural landscape management field.

BACKGROUND:

The Gettysburg National Military Park (GNMP) has made use of GIS tools on a regular basis since 1996 when full-time staff and dedicated equipment were made a part of the park’s Resource Planning Division. The GIS equipment consists of Pentium class computers running Windows and ArcINFO/ArcView software from ESRI, Inc. of Redlands, CA. GPS data collection is done using a Trimble ProXR receiver with a TDC1 data collector. GPS data is post-processed with Trimble’s Pathfinder Office software.

Parkwide GIS data creation and integration efforts at the GNMP were undertaken primarily to assist in the development of planning and archeological studies. These included the Servicewide Archeological Inventory Program, the White-tailed Deer Impact study, and the Cultural Landscape Inventory. But completion of the new General Management Plan (GMP) and Environmental Impact Statement in 1999 provided the greatest amount of support for collecting and integrating all of the existing geographic data for the GNMP area and organizing it in a consistent GIS database.

The GIS was used extensively in the preparation of the GMP. First it was used to document conditions for the entire 6,000 acres of the GNMP as of 1993 (existing), 1927 (commemorative era), 1895 (memorial association era) and 1863 (battle era). Battlefield landscape changes were then analyzed by the GIS for both large scale and small scale features. The large scale features consisted of woods, fields, orchards and roads, while the small scale features included fences, lanes and individual trees. The significance of key landscape features was also analyzed based upon both the level of battle action that actually took place and the importance of the feature from a military point of view. Finally, the GIS was used to help develop and analyze six alternatives for the GMP. In addition to calculating areas and lengths, and providing map graphics, the GIS was used to identify the key viewsheds in the vicinity of the park. The GIS also provided information on the level of impacts of the alternatives on cultural and natural resources. The use of the GIS in the preparation of the GMP is discussed more fully in an article included in the Proceedings of the 1998 Annual Meeting of the American Congress on Surveying and Mapping.1

GMP IMPLEMENTATION:

The demolition of the National Tower overlooking the Gettysburg Battlefield on July 3, 2000 was the inaugural event in the restoration of the Gettysburg Battlefield. But even before that explosive event, Gettysburg National Military Park’s newly approved General Management Plan had called for the rehabilitation of much of the battlefield to its July 1863 condition.

Landscape rehabilitation is done regularly in the NPS for designed landscapes and for natural landscapes, but rehabilitation of a battle landscape is not an easy task.2 The overall philosophy guiding the rehabilitation work at the GNMP is included in the GMP. It also includes management prescriptions that support appropriate parkwide preservation treatments and actions.

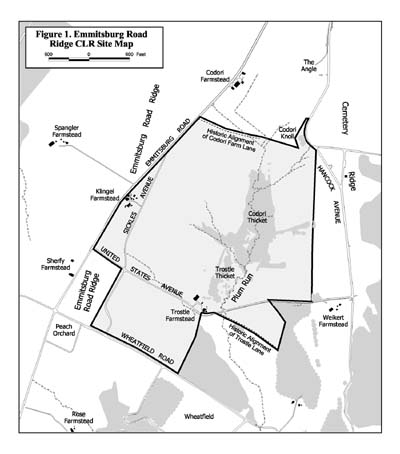

The Codori-Trostle thicket area of the park was the first part of the park where landscape rehabilitation efforts were planned for following the approval of the GMP in 1999. It was anticipated that this area would serve as the prototype for developing GMP implementation procedures that could then be followed for other areas of the park. Working in cooperation with the Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation, the GNMP began work on a mini Cultural Landscape Report that would include a detailed treatment plan. Eventually, the study area grew enough to warrant a change in the name of the project to the Emmitsburg Road Ridge CLR.

The northern boundary of this area was defined by the historic Codori Farm Lane which had been abandoned in the early twentieth century and largely forgotten since then.

CULTURAL LANDSCAPE FEATURE DOCUMENTATION:

The GIS was used to support the production of the Emmitsburg Road Ridge CLR much as it was used for the GMP. The GIS’s mapping capabilities were put to use creating period plans for the Battle, Commemorative and Current periods. A series of battle action maps for the Emmitsburg Road Ridge area was automated and georeferenced and key battle landscape features were identified in great detail. But in addition to documenting conditions, analyzing landscape changes and calculating viewsheds, GPS tools were combined with the GIS to provide control points for map registration and to navigate to feature locations in the field. Although the largest landscape feature being rehabilitated in this area is the Codori-Trostle thicket, the first feature to be rehabilitated was the Codori Farm Lane and it is the lane that this discussion will focus upon.

Numerous maps and photos document the existence of the Codori Farm Lane. But reconstructing the fences along its edges in the proper place required us to take great care in collecting and combining information from the historic maps with the existing conditions maps. The sources that were used for documentation included Nineteenth Century photographs, the G.K.Warren Map of 1868-1869, the 1895 National Park Commission Map, the Adams County 1996 Orthophotograph, and a new set of existing conditions maps. The existing conditions maps contained one foot contours and were created at a scale of 1:600 by a local engineering firm. Feature locations were based upon field measurements and photogrammetric compilation from 1998 black and white aerial photographs.

To register the historic maps to the existing conditions maps, we used building corners and fence intersections as the control points. Since the study area boundary had grown after the existing conditions maps were acquired by contract, we only had smaller scale (1:7200) base maps for some of the areas that we wanted to register the historic maps to. Therefore, we took GPS measurements at a number of the fence intersections and used those values for the existing conditions control points. The positional accuracy of our existing conditions control points were within two feet on the ground whether the point had come from the 1:600 base maps or the GPS measurements.

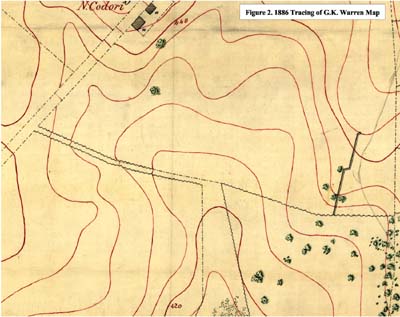

We used the G.K.Warren Maps of 1868-1869 to determine the location of the Codori Farm Lane at the time of the battle. Although the full set of original Warren maps is in the National Archives, the archives staff and their vendors could only provide a digital copy of 72 dots per inch which was too fuzzy for our purposes. Luckily, an exact tracing from that map of the part of the battlefield that we were studying had been made in 1886 by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and it now is in the Library of Congress Map collection. This map was scanned at 300 dots per inch by the Library of Congress as a part of the American Memory project and provided to the GNMP.

The scanned historic map images were first registered to the existing conditions base maps using the ArcINFO command REGISTER. This command performs an affine transformation so that if more than three control points are used (we used nine) the image locations can not be exactly matched to the corresponding map locations. 3 To get a more exact match of the historic data to the existing conditions base map, we next digitized the historic features into a vector ArcINFO coverage. These features were then rubbersheeted while the control points were linked exactly using the ADJUST command. The advantage of using a vector coverage is that you can also use the HOLDADJUST command if there are arcs that you do not want to move when rubbersheeting.

CULTURAL LANDSCAPE FEATURE ANALYSIS:

Once the historic and existing features were registered to one another, we used the GIS to make calculations of lengths for fences and lanes and to determine the acreages of orchards, woods, thickets and stream buffers. The measures were then used to help figure the costs for rehabilitating these historic features. A number of viewshed and line-of-sight analyses were also run to show the impact on the views of rehabilitating the historic Codori-Trostle thicket at different heights.

Determining the location of 1863 features in relationship to the existing conditions was accomplished as a part of the map registration process, but it was a very important part of the analysis provided for this project by the GIS. The location of the Codori Farm Lane in 1863 was also overlayed with the digital orthophotos created by the County of Adams’ Geographic Information System Office. Produced from true color photos taken in the spring of 1996 to support mapping at a scale of 1:4800, these images have a pixel resolution of 2 feet on the ground. A linear, light-colored crop mark is visible on the orthophoto in the same location where the registered historic maps show the Codori Farm Lane.

CODORI FARM LANE LOCATION LAYOUT:

Having georeferenced the historic base maps, the next step was to create waypoints along the Codori Farm Lane so that we could navigate to them using the GPS data collector. Only the fence location along the northern side of the lane was to be flagged. The fence on the southern side of the lane was simply built parallel to, and 20 feet to the south of the northern fence. We created waypoints at each end of the lane and at every point along the lane where it changed direction, where the type of fence changed, or where another fence intersected it. The waypoints were created as ArcView shapefiles and then imported to the Pathfinder Office software where they were uploaded to the GPS data collector.

Because we are within range of the Cape Henlopen DGPS radio beacon, it is possible for us to use real-time differential GPS at the GNMP. Although not as important when we are collecting data (because we routinely post-process all the GPS files that we collect), DGPS is essential for navigating to and locating features when you want to be within a meter or two.

There are a number of modes that can be used to navigate with the Trimble ProXR GPS unit, but we had the greatest success using the bearing and distance mode. Since a differentially corrected location is only calculated every five seconds, it is important to slow down your walking pace when the GPS indicates you are within about 20 feet of the waypoint. We knew we were at the waypoint when the distance to go remained in the one to two foot range even though the bearing to the waypoint kept changing. We put flags at all the waypoints and in a straight line every fifty feet between the waypoints.

The year before this project we had done some navigation tests with our ProXR unit to determine how confident we could be in our ability to navigate to a given coordinate location. Earlier, a scenic easement boundary on Gettysburg College land had been marked by buried surveyor’s pins whose coordinate locations had been determined to within one half meter when the pins were put in. Over a year later, when there were no longer any visual marks on the ground to tell us where the pins would be found, we used the GPS unit to navigate to the pins. A metal detector was then used to find the buried pins. One hundred percent of the pins were found within six feet of the location we had navigated to using the GPS.

CODORI FARM LANE FENCE CONSTRUCTION:

Building the fences that defined the Codori Farm Lane was a cooperative project between the Friends of the National Parks at Gettysburg and the Resource Planning and Maintenance Divisions of the GNMP. After the locations of the future post and rail and Virginia worm fences had been laid out using GPS, the park’s landscape preservation team prepared the work site. Fence rails, posts and cross-ties were delivered in bundles spread out along the line the lane was to follow. For the sections of the fence that were to be Virginia worm, flat stones to support the bottom rail were placed in a zigzag pattern every ten feet centered on the flagged line. Post-holes were drilled every ten feet along the part of the line that marked the post and rail fence. Actual construction of the fences was accomplished by a large number of FNPG volunteers during their spring workday. One observer reported that the scene resembled an ant colony as the volunteers, working in pairs, carefully placed hundreds of fence rails one by one along the now reestablished Codori Farm Lane.

THE FUTURE:

Since the Codori Farm Lane has been rehabilitated, we have begun landsdcape preservation treatments for the other historic features in the Emmitsburg Road Ridge study area following the recommendations in the Emmitsburg Road Ridge CLR. A number of other fencelines have been rebuilt using the process that was developed on this project, and in the coming year we expect to rebuild the part of the Trostle Farm Lane that was east of the Trostle Farm and south of United States Avenue. Rehabilitation of the Codori-Trostle thicket as well as the Neinstedt field has also begun.

On a parkwide basis, GIS tools have been used to help start work on a five year implementation plan for rehabilitation of the major large scale landscape features that were identified in the GMP. Additional treatment principles are also being developed that will be appropriate for use throughout the park.

One recent equipment upgrade that has been particularly valuable when laying out the location of historic features was the replacement of the TDC1 data collector by a TSC1 data collector. The TSC1 provides a map display so that instead of loading waypoints, the entire georeferenced historic map can be loaded as a background. In order to navigate to locations of interest on the map, we just need to observe the track of the GPS and keep walking until the track intersects the point of interest.

CONCLUSION:

Using GPS and GIS tools to assist in the rehabilitation of the Codori Farm Lane and other historic features has proven to be very useful. At the beginning of the project, the GPS was used to collect control point measurements that were then used in the rectification of historic maps and images. The ability to use GPS to navigate to waypoints for laying out the location of historic features was invaluable. Along with specialized map creation, the GIS provided integration of data collected in the field with the park’s existing base maps. Image rectification tools made it possible to fit scanned historic maps to these base maps too. Since all of this mapping was integrated using a consistent map projection, coordinates for waypoints could be derived and used in the field with the GPS data logger. GIS calculations for the lengths and areas of features helped to define the scope of work and costs that would be associated with various rehabilitation alternatives. Finally, viewshed and line-of-sight analyses were used to help confirm narrative and photographic evidence related to the height of the Codori-Trostle thicket in 1863.

Having in-house GIS and GPS capabilities has made possible quick turn around on many of the tasks associated with carrying out a cooperative project such as the rehabilitation of the Codori Farm Lane. In addition, we were able to determine with an appropriate level of confidence, the location of a missing historic feature guided primarily by maps and photos.