Acculturation & Cultural Resistance

The essence of acculturation as a process is shaping or synthesizing a new culture from the merging of two or more cultural group (Inscoe 1983:527). In British mainland North America, “African American culture” had its beginnings in the synthesis of the cultures of various enslaved African ethnics, American Indians and Europeans, mostly, the English, Irish, and Scottish people.

Throughout the 18th century Africans arriving in the Upper Chesapeake as well as in the region around the Lower James River came from the upper parts of the West African Coast, from Senagambia in the north, downward to the Windward and Gold Coasts, ending in the area of present day Ghana. Nearly three quarters of the Africans disembarking in the lower-Chesapeake area (York and Upper James Basin) came from more southerly parts of Africa, from the Bight of Biafra (present day eastern Nigeria) and West Central Africa, then called Kongo and Angola (Walsh 2001:31). The inheritance practice of Virginia gentry reinforced the concentration of enslaved people whose cultural customs had much in common. The resulting ethnic concentration of people comprising enslaved communities originally from the upper West African coast, West Central Africa and the Bight of Biafra in the Chesapeake facilitated development of their family and kinship networks, influenced their settlement patterns, and intergenerational transmission of some of the “common denominators” of their African customs and languages.

In the case of Low Country Africans, absentee landlord management, planter inheritance practices, and their majority numbers in the population by the early 18th century also impacted the cultural production that occurred among the West Central African “Kongoes,” and “Angolas” as well as the “Golas”and “Gizzis” from the Windward Coast.

Curtin (1969), Woods (1974) and Eltis et al (2001) agree that the majority of Africans arriving in the Low Country during the Colonial period were “Kongos and Angolas,” from West Central Africa. The second largest cultural group to arrive in the Low Country were from ethnic societies found along the central area of the upper West African coast in the area of present day Sierra Leone and Liberia. These ethnic groups were part of what Creel (1988) calls the “Poro Cluster (Creel 1988:17–19).”

This section of the unit examines enslaved and free people of African descent in all the Sourthern Colonies in terms of their acculturation; cultural resistance to change or cultural production.

Public and Secret Religious Experience

The first Great Awakening 1730–1740 accelerated the acculturation of enslaved Africans in Virginia to Christianity. The Presbyterians launched the first sporadic revivals in the 1740s. Baptist revival began in the 1760s followed ten years later by the Methodists. With religious conversion came education for the enslaved, at least education to read the bible. By 1771, itinerant African American Baptist preachers were conducting services, sometimes secretly, in and around Williamsburg.

Aside from the few names of runaways described as fond of preaching or singing hymns, many of the early African American preachers remain anonymous. The few names in the historical record were men of uncommon accomplishments in organizing churches, church schools, and mutual aid societies in the South and as missionaries in Jamaica and Nova Scotia. All were born into slavery in Virginia. All were Baptists. George Liele, born in 1737 was the first African American ordained as a Baptist minister. He preached to whites and slaves on the indigo and rice plantations along the Savannah River in Georgia. He was freed during the Revolutionary War by the will of Sharpe his owner. Liele was forced to flee with the British to Jamaica in order to escape re-enslavement by Sharpe’s heirs. Before he left, he baptized several converts who would continue his work in Georgia and as missionaries extend it abroad.

“Our brother Andrew was one of the black hearers of George Liele, … prior to the departure of George Liele for Jamaica, he came up the Tybee River … and baptized our brother Andrew, with a wench of the name of Hagar, both belonging to Jonathon Bryan, Esq.; these were the last performances of our Brother George Liele in this quarter, About eight or nine months after his departure, Andrew began to exhort his black hearers, with a few whites… (Letters showing the Rise of Early Negro Churches 1916:77–78)

Liele also baptized David George, a Virginia runaway, and Jesse Galphin from the Galphin Plantation and Amerindian community. These men formed the nucleus of slaves who were organized by a white preacher as the Silver Bluff Baptist Church between 1773 and 1775. When Palmer’s work was interrupted by the Revolutionary War, David George began to exhort in his absence. Later George would flee with the British to Nova Scotia where he established the second Baptist church in the province (Frey 1991:37–39).

In 1782, Andrew Bryan organized a church in Savannah that was certified in the Baptist Annual Register in 1788 as follows:

This is to certify, that upon examination into the experiences and characters of a number of Ethiopians, and adjacent to Savannah it appears God has brought them out of darkness into the light of the gospel… This is to certify, that the Ethiopian church of Jesus Christ, have called their beloved Andrew to the work of the ministry…. (Letters showing the Rise of Early Negro Churches 1916:78)

As the 18th century ended, the First African Baptist Church in Savannah erected its first building. By 1800, Bryan’s congregation had grown to about 700, leading to a reorganization that created the First Baptist Church of Savannah. Fifty of Bryan’s adult members could read, having been taught the Bible, the Baptist Confession of Faith, and some religions works; and three could write. First African Baptist established the first black sabbath school for African Americans, and Henry Francis, who had been ordained by Bryan, operated a school for Georgia’s African American children.

Development of African Methodism was largely a northern phenomenon in the 1780s.

Cultural Resistance: “Gimmee” That Old Time Religion!

Some Africans resisted Christianity. Raboteau and others point out that a number of Africans were Muslims and that they never relinquished their faith in Islam.

There is relatively little historical documentation on 18th century enslaved Muslims in North America making discussion of them less conclusive than that about enslaved Africans who were Christians or who practiced indigenous traditional African religions. Some scholars believe that perhaps as many as 10% of Africans enslaved in North America between 1711 and 1715 were Muslims and that the majority probably were literate (Deeb 2002).

Islam was firmly established as a religion in Ancient Mali as early as the 14th century. As in other parts of the world, Islamic conversion was effected through trade and migration far more often than by force. In West Africa, prior to the 18th century, much of this conversion occurred through interaction of West Africans with Islamicized Berber traders, who controlled the trans-Saharan trade routes. From the early 17th century through the late 18th century, the influence of Islam spread among the people in many parts of the Senegambia region, the interior of Sierra Leone, the Gold Coast and as far south as the Bight of Benin.

According to Gomez, the widespread influence of Islam in West Africa makes it highly likely that the numbers of Muslim Africans enslaved was probably in the thousands (1998:86). The recurrence of Muslim names among American-born Africans running away from enslavement in 18th century South Carolina offers some evidence of Muslim people’s presence and their efforts to continue their faith (Gomez 1998:60). Gomez (1998) grounds his argument about the Muslim presence among Africans enslaved in North America and the African Islamic context of slavery in examination of original French documents.

Sylviane A. Diouf, (1998), also basing her research on primary source French documents, estimates at least 100,000 Africans brought to the Americas were Muslims, political and religious leaders in their communities, as well as traders, students, Koranic teachers, judges and, in many cases, more educated than their American masters. According to Diouf, the captivity of several of the notable Muslim slaves who left narratives of their experiences grew out of complex religious, political, and social conflicts in West Africa after the disintegration of the Wolof Empire. Diouf argues, the religious principles and practices of African Muslims, including their literacy, made them resistant to enslavement and promoted their social differentiation from other enslaved Africans. As slaves, they were prohibited from reading and writing and had no ink or paper. Instead they used wood tablets and organic plant juices or stones to write with. Some wrote, in Arabic, verses of the Koran they knew by heart, so as not to forget how to write. According to Diouf, Arabic was used by slaves to plot revolts in Guyana, Rio de Janeiro and Santo Domingo because the language was not understood by slave owners. Manuscripts in Arabic of maps and blueprints for revolts also have been found in North America, Jamaica and Trinidad (Diouf 1998).

The earliest Muslim account of his enslavement in North America was written down and published in 1734 by Thomas Bluett, a white resident of Maryland. It essentially is an account of how Job Ben Solomon, son of a Muslim cleric, came to be enslaved and how he was liberated later once his aristocratic heritage was discovered (Bluett 1734).

The 19th century manuscripts of Omar ibn Said (1770–1864), provide additional primary source evidence upon which scholars base their contention that many enslaved Africans in the colonies were Muslims. Said, a Senegalese was brought to North Carolina to be enslaved in 1807. In a symposium on “Islam in America” held at the Library of Congress, Derrick Beard, a preeminent collector of 18th, 19th and early-20th century African American decorative arts, photograph and rare books, views Said’s diary as a unique autobiographical manuscript ( Deeb 2002). Omar bin Said a well-educated, enslaved Muslim wrote in Arabic and left behind a number of manuscripts, 13 of which are extant. Although it is said that he converted to Christianity there is evidence to suggest otherwise. Just before his death, in 1864, a North Carolina newspaper published a photo of what it called the “The Lord’s Prayer,” written in Arabic by him. In fact it is Sura An Nasr (Chapter 110) of the Koran. Said had written it some forty years after enslavement, when he was around 90 years old, shortly before his death.

Diouf contends many other enslaved Muslims, like Said, went to great efforts to preserve the pillars of Islamic ritual because it allowed them “to impose a discipline on themselves rather than to submit to another people’s discipline” (1998:162). Diouf identifies references in the historical literature of slavery to the persistence of Islamic cultural practices among enslaved Muslims such as the wearing of turbans, beards, and protective rings; the use of prayer mats, beads, and talismans (gris-gris); and the persistence of Islamic dietary customs. For Diouf, saraka cakes cooked on Sapelo Island in Georgia were probably associated with sadakha or meritorious alms offered in the name of Allah. She speculates that the circular ring shout performed in Sea Island praise or prayer houses might have been a recreation of the Muslim custom of circumambulation of the Kaaba during the pilgrimage in Mecca. Arabic literacy, according to Diouf, generated powers of resistance because it served as a resource for spiritual inspiration and communal organization, “A tradition of defiance and rebellion (1998:145)."

Yarrow Mamout, one 18th century enslaved Muslim for whom some documentation is available, was born in Guinea, West Africa between 1704–1736 (Lesko, Babb and Gibbs 1991:11–12). Yarrow Mamout was a teenager, about 14 years old, when he was brought by a slave trader to the Virginia – Maryland area that later became incorporated as Georgetown. He was purchased by Samuel Beall of Montgomery County and willed to his son Brooke. In 1792 Brooke gave Yarrow the job of making bricks for his new house in Georgetown and promised to free him when the job was done. Although Brooke died before manumitting Mamout, Brooke’s widow, Margaret, kept the promise and freed Yarrow in 1797.

Mamout acquired wealth and property in Georgetown. He also invested in the Columbia Bank, one of Georgetown’s first banks. He lived the rest of his life in Georgetown, where he died in 1824, some say at the age of about 88. Others say that he was over 100 years of age (Lesko, Babb, and Gibbs 1991; Johnston 2004.)

While recording likenesses of distinguished Americans in Washington DC, in 1819, Charles Wilson Peale heard about Yarrow Mamout. Intrigued by Mamout’s great age, reputedly 134 years at the time, and the fact that he was a practicing Muslim, supposedly a rarity in 19th century America, Peale sought an opportunity to paint his portrait.

Peale recorded the accounts Mamout gave of his life while sitting for his portrait. Peale wrote in his diary, “I spent the whole day and not only painted a good likeness of him, but also the drapery and background.” Peale recorded Mamout’s stories about his capture in Africa, coming to the American colonies on a ship, and his life enslaved in Maryland. Peale’s portrait is held by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

A second portrait of Mamout, painted by Georgetown resident James Alexander Simpson (1822) hangs in the Peabody Room at the Georgetown Public Library. Mamout’s house has long since been demolished however the National Park Service includes the address of Mamout’s former residence in its Black Georgetown Tour.

Priests of African traditional religions often continued to hold those beliefs. Even though over time the majority of Africans and African Americans became Christians, African Christianity and church rituals often incorporated African beliefs and rituals. Some scholars suggest that Africans readily acculturated to Christianity, especially those from West Central Africa, because of prior exposure to Christianity. Old ways died hard and some never died out. Thornton points out that none of the Christian movements in the Kongo brought about a radical break with Kongo religious or ideological past. Instead African Christianity simply emphasized already active tendencies in the worldview of the Kongo people (Thornton 1983:62–63). As early as 1777, Oldendorp, a Danish missionary in the West Indies described enslaved “Kongos” acculturation to Christianity from first person interviews he conducted among enslaved people in the Danish West Indies saying that the “congoes” in comparison to other African ethnic groups:

“[H]ave for the most part, a recognition of the true God and Jesus Christ, and are more intelligent and cultured than other Blacks. This is due to the influence of the Portuguese who, from their arrival on the coast, [of West Central Africa] made an effort to enlighten and better this unknowledgeable people … those who live far from them deep in the inland had a religion that was a combination of Christian ceremonies and heathen superstitions… Only the Congo, who through the Portuguese are familiar with the Christian teaching have been baptized and have monogamous marriages… ([Oldendorp [1877])

One of the central beliefs of the Kongo, for example, emphasizes that human beings move through existence in counter-clockwise circularity like the movement of the sun, coming into life or waking up in the east, grow to maturity reaching the height of their powers in the north, die and pass out of life in the west into life after death in the south then come back in the east being born again (Fu-Kiah 1969; Thompson 1984; McGaffey 1986). Many West African groups believe in life after death and some believes that people are reborn in their descendants. These ideas, although in a different context, blended well with Christian beliefs in life after death and with the Christian belief being born again.

Other West African groups stressed the necessity of performance of proper funeral rituals in order that the spirit might live comfortably in the afterlife until rebirth. What little we know of colonial African American religious beliefs and practices are almost all associated with archeological evidence of their mortuary practices and English descriptions and laws relating to slave funeral and burial rites. These sources suggest religious acculturation among slaves was not universal and that it proceeded both slowly and unevenly. Artifacts uncovered by archeological excavation may mean that African American Christians on Sunday may well have continued at other times to participate in African sacred and healing rituals.

Cultural Resistance: Burial Rites and Grave Goods

There are few descriptions of colonial African funerals and burial rites. Instead one must rely upon the legislated prohibitions to surmise what they must have been like. In 1687, for instance, the laws of Northern Neck of Virginia prohibited public funerals by slaves because authorities feared that they helped to hatch a recent conspiracy. It said that “Negroes” made use of the “great freedom and liberty” that many masters gave them permission to meet in great numbers to make feasts and to hold “Funerals for Dead Negroes.” Prohibition of night funerals suggests that late 17th century Africans continued the West African custom of holding funerals at night. While the custom may have been West African it also served practical purposes for enslaved people on Southern plantations. At night, slaves from neighboring plantations could sneak away to join in the funeral celebration. The enslaved African funerals often included a long procession in which all of the people would pass by the grave, shouting, chanting, and singing.

“‘They cry and bawl and howl around the grave and roll in the dirt, and make many expressions of the most frantic grief … sometimes the noise that they make may be heard as far away as one or two miles (Rice 1809 as cited in Morgan 1998:644.).’”

Whites felt threatened by this display and saw it as pagan or even satanic. But the enslaved Africans saw it as a necessary way to put the dead to rest. They sent their loved ones to the next world with grave goods for their life in the next world and sometimes positioned them facing east to be ready to rise up, and be born again.

Archeological excavations at Utopia quarter near Carter’s Grove Virginia examined African remains and grave goods. Most bodies were buried in European-style wooden coffins. Walsh suggests the variance in body orientation and position indicates a mixing of African and European beliefs about death. Most bodies were buried along an east-west axis with the heads laid in the west, eyes facing east. Two adults faced west with head in the east. The goods placed in the graves included a fine bead necklace, tobacco, and pipes, ritual practices reported among different West African groups of the day and commonly found in archeological excavations of African and first generation creole-born slaves in Barbados (Walsh 1997:104–106; Handler and Lange 1978).

Pipes and tobacco were frequent grave goods in West Africa, and wealthy Ashanti were buried with gold-ornamented pipes. Historical anthropologist Jerome Handler reports the recovery of a Ghanian pipe from a Barbados burial as one of the few African artifacts to make the trans-Atlantic passage (Handler and Lange 1978).

The decorative motifs found on clay pipes found in various Chesapeake archeological sites are thought by Emerson to be West African in origin. Others contests this assertion, offering evidence that American Indian, African and European Chesapeake pipes shared many characteristics. Based on both their arguments, it seems all three groups were involved in a shared acculturative process (Emerson 1999; Mouer et al 1999).

Cultural Resistance: Secret Rites and Rituals: Shells, Spoons, Crystals and Beads

Cowery shells unearthed at the Atkinson site, the remains of a small late 17th-century farmstead near Carters Grove Plantation.

Archeological excavations have unearthed objects that Africans may have used as charms and objects believed to be imbued with magical powers as protection from conjure spells (Franklin 1995; Morgan 1998). In colonial America both Africans and Europeans put great stock in the control of disease through charms and conjuration.

Archeological excavations of places where Chesapeake slaves lived, worked or were buried during the colonial period have uncovered coins, stones, shells, spoons, crystals and beads. Analysis of such artifacts that people used or buried with their dead, offer clues to their cultural practices, socio-cultural roles and their beliefs about life and death. The artifacts uncovered in Virginia reveal continuing elements of African culture at the sites of several slave quarters adjacent to Carter’s Grove and Kingsmill. Beads, two cowry shells and a spoon with a pierced hole that may have been worn as jewelry, polished animal horns and lead disks were found.

Pewter spoons, clay tobacco pipes, and a shell from the Rich Neck Slave Quarter site. These artifacts have been modified for specific, but as-yet unidentified, purposes.

These artifacts may have been used as personal adornment by enslaved Africans and African Americans or in their African ceremonial or religious practices. Rich’s Neck excavation also unearthed Virginia halfpennies, pieces of Spanish silver money and even less-expected silver shirt studs and jeweled cuff links. Other personal luxuries found at the Utopia site included decorative buckles, a faux emerald, and a pewter toy watch (Walsh 1997:197–199).

During the excavation of the ground floor of the Charles Carroll House in Annapolis, Maryland, archeologists found a number of quartz crystals that have also been interpreted as suggesting continued secret African religious rituals.

The Carroll House was a frame house on property purchased and occupied from the early 18th to the 19th centuries. The ground floor of the Carroll House was a working space and possibly a living space for enslaved African Americans. Ceramics, coins, and other artifacts found in the same layers as the Carroll House crystals helped date time them to 1790–1820. Similar artifacts have also been found in other archeological excavations in Maryland and Virginia and all in contexts associated with the working and living spaces used by slaves.

Along with the Carroll House crystals, archeologists found pottery marked with what appears to be a Bakongo Cosmogram, coins, reworked glass or stones, and beads. The crystals and other items found are similar to materials used in the Kongo to make Nkisi, sacred ritual objects that are believed to have potential spiritual powers. Nkisi made of these particular objects are believed to heal swelling of the body or boils. Lynn Jones comments that the assemblage of crystals, smooth black stone, ivory and brass rings, a glass bead, bones and crab claws found in the east wing of the Carroll House may be the material expression of such beliefs held by enslaved Africans (Jones 2000).

The 67 enslaved servants who supported the George Washington household at Mount Vernon lived in a structure known as the House for Families during the 18th century. Archaeologists recovered one unusual and suggestive artifact from an excavation of this site that they believe represents Mount Vernon's best candidate for an object reflecting an African cultural tradition (George Washington’s Mount Vernon, 2004). The artifact, a baculum (penis bone) of a raccoon, had been modified by incising a line encircling one end. Only a few raccoon elements are included among the 25,000 bones recovered from the House of Families cellar. The bone, they speculate, seems to have served a special function, possibly as some sort of ceremonial device or decorative item.

Raccoon bacula are relatively large (from 93 to 111 millimeters) and distinctively curved. The male raccoon is known to be sexually aggressive. The combination of these characteristics suggests its selection as a fertility symbol suspended around the neck. The archeologists point out that similarly modified bacula have been excavated from numerous prehistoric American Indian sites and therefore it may reflect what they call a “pan-cultural folk practice (George Washington’s Mount Vernon 2004).”

The excavation of all of these artifacts may be evidence that even though enslaved, some Chesapeake people of African descent who appeared to be acculturated to English customs and culture continued to hold “African” beliefs that they expressed through rituals and body adornments.

Culture Change: Social Autonomy and Culture Production

On the eve of the Revolutionary War, African peoples had been living in North America for 150 years. While there were fresh in fusions of Africans directly from the continent and others from the West Indies, most enslaved African peoples were new generations, American-born with no first hand knowledge of Africa. While they may have internalized African systems of meaning as expressed in their sacred beliefs and religious cultural performance, free American-born Africans were probably the most acculturated of all African peoples in the colonies. They tended to have some formal education, be literate, and have some skill with which to make a living.

Buying themselves and their families out of slavery was one source of the emerging class of free African Americans in the 17th and early 18th century. Other enslaved African Americans, usually mulatto children of white indentured servant women, became free after fulfilling long years of indenture. Other African slaves, favored mistresses, and mulatto offspring of white slave owners as well as elderly slaves who had given a lifetime of service were often freed in the last will and testament of the slave owner.

The numbers of free African Americans expanded rapidly during the Revolutionary War. Many were runaways who lost themselves in urban populations of African Americans, swelling the ranks of the free. In the last decade of the 18th century free light-skinned émigrés from Santo Domingo fled the Haitian Revolution to southern ports including Charleston, further increasing the size of the free African American population in the South (Berlin 1974:10–55; Poole 1994:4–8).

Free African Women & the Courts

In 17th century Chesapeake, free African women, particularly those who had no husbands, had to struggle to maintain their freedom in the face of laws that would indenture them if they did not pay their tithes or taxes. Furthermore, they had to struggle to keep their children from becoming enslaved. If these African women exhibited no other signs of acculturation, they definitely understood English law and how to use the court system to their own advantage and to protect their children. They used the courts and formed alliances with white women in order to resist re-enslavement and to insure their children’s future freedom.

Free African women burdened with paying their own tithes turned to the courts to arrange apprenticeships terms for their children and to protect them from exploitation and permanent enslavement by unscrupulous white masters. After permanent enslavement laws were passed, free African women seemed to have greater difficulty in establishing their right to voice consent to a child's apprenticeship arrangements. By making their children’s indentures a matter of public record, some African mothers may have hoped to fend off their children’s permanent enslavement (Brown 1996).

By the 18th century, most women of African descent who were not enslaved were American-born, some were mulattos,. All of these free African Americans may have had prior first-hand experience with courts establishing their own status as free persons or negotiating indentures. Indentured African American women entered into alliances with the white women for whom they worked to enable them to keep their children in the same indenture as themselves. Indentures for their children not only paid for the children’s livelyhood it also offered opportunities the mothers were probably unable to provide. For example, in 1729, Jane Hall negotiated an indenture for her daughter Ann with conditions that she would be taught to read, sew, knit and spin before being released at age eighteen. Other African American mothers entered agreements that their children be taught trades or be baptized and taught Christian prayers (Brown 1996).

Benjamin Banneker: A Free African American Man

Benjamin Banneker’s father, Robert, was a farmer who had been manumitted from enslavement. His mother was Mary Banneky the daughter of Molly Welsh, a former English indentured servant and an enslaved man who worked on the farm where Mary was indentured. Banneker’s father took his mother’s surname when they married.

Benjamin was taught to read and write by his grandmother Molly Welsh. He received some formal education at the Quaker School although once he was old enough to help on his parent’s farm he had to end his formal education. Essentially, Banneker was a self-taught man. He learned to play the flute and violin. After studying the workings of a watch, he built a wooden clock that lasted fifty years. He studied astronomy and mathematics through books loaned to him by an acquaintance (Blacks in Government 2003). At the age of 57 when many people look forward to retiring and without any help, according to Lumpkin (1996) with only…

…a few semesters of elementary schooling in his childhood, Banneker taught himself the algebra, geometry, logarithms, trigonometry, and astronomy needed to become an astronomer. He also learned on his own how to use a compass, sector, and other instruments to make astronomical predictions, including that of eclipses.

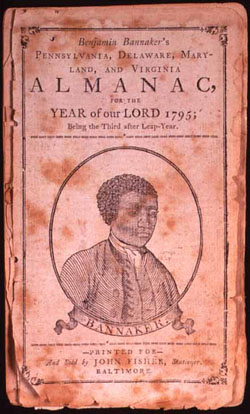

Known as America’s first African American man of science, he wrote and published an almanac.

In 1791, he was appointed by George Washington at the request of Thomas Jefferson to be part of a three man planning team to survey the future District of Columbia. Pierre L’Enfant, the architect in charge was later fired. He left the team taking his plans with him. Banneker recreated the plans from memory in two days. Banneker was honored by a United States postage stamp in 1980 (Blacks in Government, 2003).

In 1983, the Baltimore County Department of Recreation and Parks purchased a portion of the original Banneker property to establish a commemorative park. That same year, Robert J. Hurry conducted an archaeological survey that resulted in identification of the location of the archaeological remains of the Benjamin Banneker farmstead.

The Banneker Site (18BA282) is the 18th-century home of Benjamin Banneker in Baltimore County, Maryland. Banneker farm, where he lived between 1737 and 1806, consisted of two wooden dwellings with cellars from two periods, an orchard, a fence, and a cemetery where Benjamin Banneker and his family are buried.

The Banneker Site has yielded valuable information about the life and material culture of Benjamin Banneker, an important figure in American history, but it has also provided details about the lifestyles of free African Americans living in Maryland during the 18th and early 19th centuries. Over 28,000 artifacts were recovered from the Banneker Site, with the majority associated with the Banneker occupation. Artifact analysis was used to detail not only how Banneker’s family lived as free African Americans in a plantation society, but how Benjamin Banneker’s lifestyle changed during his life. This analysis, combined with historical research, suggests that prior to 1760 the Bannekers depended on wild species and animals raised on their farm, but purchased more food at the local store, Ellicott & Co., after that date. Other recovered objects reflect various activities that occurred at the Banneker homesite. Nine slate pencil fragments, a possible slate tablet, and a ground glass lens for a telescope or other optical instrument represent some of the objects that Banneker probably used for his scientific research. (Hurry 2002).

Although a free man from birth Banneker, was an advocate for freeing all persons held in bondage. To this end, he wrote to Thomas Jefferson, then Secretary of State, reminding him that the words written in the Declaration of Independence should be truly applied to “all men.” Read the letter written by Banneker.

Banneker also sent Jefferson a copy of his Almanac. Jefferson responded in a letter that he too wanted to see “such proofs as you exhibit, that nature has given our black brethren talents equal to those of the other colors of men” …and that he wished to see a good system for “raising the condition, both of their … [African Americans] body and mind…” (Jefferson 1791). Jefferson sent Bannekers Almanac to the Academy of Sciences in Paris as he put it, “because I considered it as a document, to which, your whole color had a right for their justification, against the doubts which have been entertained of them (Jefferson 1791) Banneker’s entire life was in itself an act of resistance to the commonly held stereotypes of African people.

The first census of the United States in 1790 found Virginia with 12,866 free “Negroes.” Accomack County, where the 17th century free Africans had lived, was still the region in the South most heavily populated by free African Americans. By the turn of the century the number of free African Americans in Virgina had increased by 7627. In the upper southern states of Maryland and Virginia free people of color were dispersed throughout the states. Only 4.5% of free African Americans lived in Richmond and Petersburg. Similarly, 323 (4.0%) of Maryland’s free African American population lived in Baltimore. In contrast, free African Americans further south were mostly found in cities Savannah was the home of 112 or 28% of Georgia’s free African Americans, while Charleston was the most heavily populated urban area in the South. In all, (586) or 33% of all free African Americans in South Carolina lived in Charleston in 1790 and their numbers had increased by 1800 (Berlin 1974:55; United States Historical Browser, U.S. Census 1790).The majority of these Charlestonians were mulattos (Fitchett 1941).

While great disparity existed between the social positions of Whites and free African American positions in Charleston society, Berlin emphasizes the commonalities in the social experiences of free people of African descent and those enslaved (Berlin 1974:5–10) Others argues that social mobility and economic opportunities were limited and Whites passed laws to deny free African Americans their civil rights. The reaction of free people of color was to establish separate social institutions and obtain substantial wealth as artisans and entrepreneurs (Poole 1994:5; Fitchett 1940, 1941). They distinguished themselves from other African Americans through acculturated customs and, particularly in the case of mulattos, assimilation of white American prejudicial social attitudes toward darker skinned and poor people (Poole 1994; Fitchett 1940).

Free people of African descent were in the minority yet, in spite of their cultural assimilation, the social institutions they formed were reminiscent of traditional social organizations such as the Poro and Lemba societies found in regions of West and West Central Africa highly represented in the slave trade to the Chesapeake and South Carolina (Creel 1998; Janzen 1979).

The secret societies that arose in West Central Africa, most notably the Lemba, as a concomitant of the slave trade created a family-like social organization in a different social institution with the same objectives, world view, moral philosophy and promoting the same social ethics as the earlier traditional religion and lineages (Janzen 1982, 1979; Turner 1968). On the Windward coast the Poro-Sande societies reinforced a traditional life style, a sense of community and societal bonds that transcended family, clan or ethnic barriers (Creel 1988). The societies and the churches formed by Charleston African Americans also promoted high ethical standards, reinforced a sense of community, and societal bonds among free African Americans who were greatly outnumbered by both enslaved peoples and the English.

Cultural Change: Social Class Differentiation The Brown Fellowship Society

By the last quarter of the 18th century many enslaved and free “Negroes,” as the English called them, were not only completely acculturated into Europeans culture in their dress, gender-related work roles and diet but also had assimilated English beliefs in race-based superiority. The members of the Brown Fellowship Society of Charleston, South Carolina believed in superiority based on skin color. Their Rules and Regulations, referred to themselves as “we, free brown men” … when referring to other African Americans, the title “poor colored” was used (Poole 2004:6–9).

In 1790, five free African Americans founded the Brown Fellowship Society, the oldest funeral society in Charleston. With color restrictions and a 50-dollar membership fee, the organization appealed to an elite group of mostly light-skinned mixed race men who wished to establish a social position for their families similar to that of the white aristocracy. The Brown Fellowship Society provided services for its members, including education, medical care, and support for widows and orphans of the deceased. The motto “charity and benevolence” did not apply to those African Americans of darker skin color or lower social status, evidence of a growing class differentiation among African Americans based on color and status as free or enslaved.

Free dark-skinned African American elites followed the lead of free mulatto elites. They reacted quickly to the formation of the Brown Fellowship Society, forming the Society of Free Dark Men of Color in 1791 (Curry 19821:150). The society served a similar purpose for the free dark elite as the Brown Fellowship Society did for the mulatto elite. It gave free dark-skinned men an organized social outlet, allowing them to embrace their darkness. It gave them an identity, as did the Brown Society give the mulattoes an identity. These dark men were defining themselves as different from both slaves and free mulattoes. They had educational and mutual aid objectives. Formation of these societies attest to the growing awareness among a significant number of free African Americans that they were a distinct social group with their own specific needs and that their greatest security was in the invaluable labor they supplied (Hinks 1997:25). The lighter skinned free elites positioned themselves as a “buffer” between white and black society. The dark elite lacked the numbers and thus the resources to form a status group comparable to that of the mulatto elite, but in the face of both white and mulatto discrimination, free dark-skinned elites had little choice but to close ranks and defend their portion of borrowed ground (Poole 1994:7).

Other mutual aid, burial and benevolent societies that emerged in northern colonies developed into churches, abolitionist and other counter cultural resistance organizations. Migration, Military Service, Litigation, and Maroonage were the main avenues of counter-cultural resistance by enslaved people in the southern colonies.