|

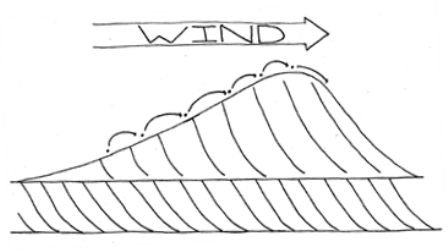

Q. How do we know this was a desert? A. We can tell that much of this sandstone is made up of dune deposits because it displays enormous cross-bedding. Cross-bedding is the set of swooping lines you can see as you look at an outcrop, and represents the steep sides of the dunes, preserved as the wind drove the dunes across the desert. The constant flow of any kind of fluid can form cross-beds, but ones this size can only be formed by wind.

National Park Service

National Park Service As you explore Dinosaur National Monument, keep an eye out for cross-bedded rocks. You might find that they're more common than you think!

National Park Service Q. Where did the animals and plants that lived in this desert get their water? A. In addition to dune deposits, the Q. How do we know there was water? A. The interdunal deposits in the

National Park Service Q. Where did the water come from?

National Park Service |

Last updated: February 24, 2015