From her Spanish Revival home in the el Condado suburb of San Juan, Puerto Rico, Dra. Concha Meléndez Ramírez (1895-1983) built a literary career as one of the most memorable voices of Puerto Rican culture. As a member of the famed “Generation of Thirty,” she took part in a creole literary movement that reimagined a uniquely Puerto Rican cultural identity under American rule. After Puerto Rico became an American possession, many Puerto Ricans romanticized their Hispanic past and embraced the jíbaro, or country peasant, as a distinct national symbol in protest of American imperialism.

By the early 1900s, people like Dra. Ramírez had joined a global community in which the United States had become a fixed presence. Territorial expansion and victories in two world wars had repositioned the United States at the top of a new world order. So much so that, by 1941, Time magazine publisher Henry Luce had declared the twentieth century the “American Century.” While some felt that the nation’s newfound influence placed America in a position to reshape the world in its own image, others like American vice president Henry Wallace called for the nation to promote American ideals abroad—such as democracy, equality, and freedom—in order to make the 20th century “the century of the common man.”

The United States would spend much of that century struggling to successfully address its many interests at home and abroad. America faced a recurring dilemma—how can the nation uphold its ideals of freedom, liberty, and equality within the complex political realities of a globalizing world? Would they support democratic elections abroad even when elections placed communist leaders in power? Would they endorse the political independence of nationalist groups in the colonies of their European allies? Various presidential administrations and policymakers would find different answers to these often conflicting issues and shaped the United States’ role in the world community in the process.

But, America has never existed in isolation. The “New World” had loomed large in the minds of European explorers since the 1500s as a promise of untold riches and a space for conquest. Encounters between European settlers and indigenous peoples were marked by warfare, displacement, and disease. They also created complex networks of trade, alliances, and kinship. This movement of people, ideas, and goods forged ties far beyond the Atlantic world. Sugar from Barbados, fur from the great lakes region, and the forced importation and enslavement of peoples from Africa’s Gold Coast were all integral to the economic growth of colonial America.

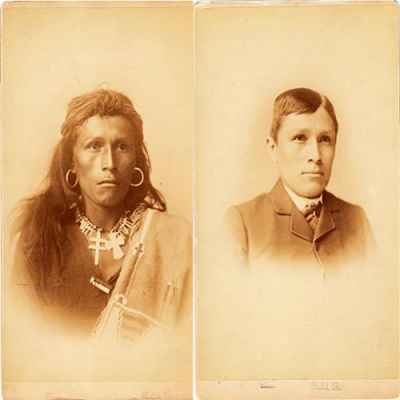

During the 1800s, European-American settlers embraced the concept of Manifest Destiny and pushed the nation’s borders further westward towards the Pacific. While indigenous Native Americans were displaced or forcibly assimilated into Anglo-American culture, the nation began looking to “new frontiers” in Asia and elsewhere for new markets, raw materials, and opportunities for investment.

The wars of 1898 ushered in a new age of American imperialism abroad. By 1900, the United States had acquired Puerto Rico, Guam, Cuba and the Philippines as territorial possessions. In 1893, European American planters led a political coup to depose Hawaii’s Queen Liliuokalani. After the coup, the United States officially annexed the Hawaiian Islands. Meanwhile, the Roosevelt Corollary (1902) to the Monroe Doctrine proclaimed that the entire Western Hemisphere fell under America’s “sphere of influence”—much to the surprise of many of the people living in that region. As the United States proclaimed itself a champion for independence movements abroad, it often found itself occupying countries that it had set out to liberate—such as Nicaragua (1912-1933), Cuba (intermittently, 1898-1922), Haiti (1915-1934), the Dominican Republic (1916-1924), and The Philippines (1898-1946).

This rapid expansion created new opportunities and dilemmas for the United States. As the nation’s borders shifted and expanded, more people fell within America’s sphere of influence. At the same time, immigrants began to arrive in the United States in unprecedented numbers and dramatically altered the country’s ethnic make-up. These developments forced the United States to address new and pressing questions about national identity: What does “America” look like? And who is entitled to the rights and freedoms promised by the nation’s highest principles?

During the 1800s, millions of immigrants arrived at America’s shores from Europe and Asia. Many fled persecution, violence, and famine. Nearly all of them looked to their adopted country for greater opportunities to provide for themselves and their families. While American industrialists welcomed the influx of new workers, others worried that the dramatic increase of immigrants threatened the country’s traditionally Anglo-Saxon ethnicity. Nativists supported immigration policies that limited immigration on the basis of race. The Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) became one of the first of these laws and prohibited the immigration of Chinese laborers. Other laws, such at the Immigration Acts of 1891 and 1903, restricted immigration according to Victorian social mores and excluded prostitutes, homosexuals, and polygamists. By the 1900s, immigration stations became spaces for U.S. officials to categorize immigrants as potential new citizens or as “undesirable” aliens. During the civil rights era, many of these racist immigration restrictions were removed by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

As Americans debated the state of American citizenship at home, their leaders struggled to promote their vision of freedom and democracy abroad. With the First World War drawing to a close, President Woodrow Wilson called upon European leaders to support the principle of “self-determination,” or the ability of a nation to declare its own sovereignty. Nationalist groups within European colonies quickly embraced this call but were soon disappointed. The United States frequently defended the empires of its European allies in an attempt to halt the spread of communism and socialism across Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.

The first two decades of the 1900s was a period of momentous change—political revolutions, widespread migration, and social upheaval placed Americans in contact with diverse people, ideas, and customs. American writers and artists responded to the rapidly changing world around them in their work. American writers that came of age during World War I, often referred to as the “Lost Generation,” dealt with themes such as the horrors of war, the excesses of modern society, and the death of the American dream. The writings of Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald voiced many of the anxieties of the years following World War I. A growing community of American expatriates also strongly influenced intellectual circles throughout Europe. Writer and art collector Gertrude Stein held famous weekly salons at her Paris home and entertained artistic and literary elites like Hemingway, Sinclair Lewis, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso.

Many other Americans also saw themselves as members of a global community. African American intellectuals and activists increasingly began to link their struggle for equality at home with liberation movements abroad. By the 1900s, the Marcus Garvey Movement had introduced Black Nationalism and Pan-Africanism to working-class African Americans throughout the country. For the next several decades, a thriving international black press informed members of an African diaspora of freedom movements across the globe. During World War II, members of the Black Freedom Movement formed the International Committee on African Affairs (later renamed the Council on African Affairs) to support international anti-colonial movements. Jazz performers like Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, and the Dave Brubeck Quartet travelled the world for the State Department during the Cold War—the decades-long struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union for political and ideological supremacy. While abroad, they used their platforms as “Goodwill Ambassadors” to soundly condemn colonialism abroad and America’s Jim Crow laws at home.

The political conflicts between the United States and the Soviet Union often overshadow other important developments of the 1900s. This period also saw the rise of organizations that looked for new ways to encourage peaceful, thriving co-habitation amid ongoing political tension. As members of intergovernmental organizations, humanitarian aid programs, educational agencies, and NGOs, American citizens have been important actors for international peace and cooperation. They have provided medical aid as members of the Red Cross and Doctors Without Borders. They’ve built schools, encouraged scholarship, and supported local businesses while serving in the Peace Corps and working with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and the Rockefeller Foundation. They have championed human rights around the world with Amnesty International. They have proven that when common people unite for a great cause, they produce extraordinary results.

For the remainder of the century, the United States’ responses to conflicts at home and abroad would be shaped within the greater context of the Cold War. As the United States turned to the task of rebuilding Europe, politicians and private citizens alike renewed debates about where U.S. interests laid and who were threats to those interests. The Truman Doctrine (1947) firmly divided the world into two camps for many Americans—an American vision of democratic capitalism versus the communist Soviet Union. The United States’ foreign policies— involvement in foreign wars, military coups, nationalist movements, and uneven support of decolonization—were all measured in their ability to halt the spread of communism.

In 1996, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright declared that the United States had become the world’s “indispensable nation.” Certainly, the United States has left a lasting impact on the global community. At the same time, America is itself a product of global exchange. The empires of indigenous nations, the British colonies of the eastern seaboard and the Spanish southwest, to the immigrant communities arriving from Asia, South American, and the Middle East during the 20th century have each transformed the North American continent. As we’ve entered the new millennium, technological advancements—from more efficient modes of transportation to online social media platforms—have made the world beyond our physical borders just that much closer than before. In an age where smartphones can help launch political revolutions, we find ourselves on the precipice of an ever-shrinking world. In the midst of these changes, the United States will continue to strike a measured balance between its core values, its vital interests, and the diverse people that call it home. As the nation’s storyteller, the National Park Service preserves and interprets their voices and experiences in our parks, trails, and historic sites into the next century.

Visit the National Park Service Telling All Americans' Stories portal to learn more about American heritage themes and histories.

Last updated: February 9, 2017