The War of 1812, Canadian historian Charles Stacey once remarked, is “one of those episodes in history that make everybody happy, because everybody interprets it in his own way.”

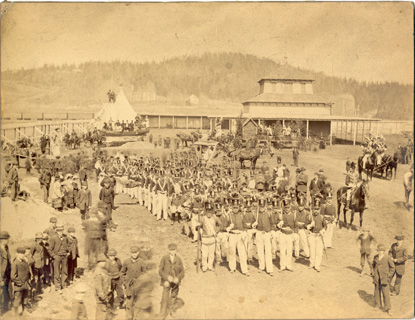

Courtesy of New Brunswick Museum, Saint John, New Brunswick

Canadian historian Charles Stacey explains the confusion over who won the War of 1812:

The Americans think of it as primarily a naval war in which the pride of the Mistress of the Sea was humbled by what an imprudent Englishman had called “a few fir-built frigates, manned by a handful of bastards and outlaws.” Canadians think of it equally pridefully as a war of defence in which their brave fathers, side by side, turned back the massed might of the United States and saved the country from conquest. And the English are the happiest of all, because they don’t even know it happened.

Stacey was absolutely correct, as perhaps no other conflict in the western world has been subject to so much confusion and so many conflicting claims—to this day.

In British North America, as Canada was known before it formally became a nation on July 1, 1867, the effects of the war were uneven. In the maritime provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, the conflict had introduced affluent times, fuelled by increased British government expenditure and a demand for foodstuffs and raw materials. Between 1812 and 1814, Canadian privateers—who had enjoyed many successes since the beginning of the French wars in 1793—depreciated the American Atlantic coastal trade. One third of all US flag vessels captured during the war were taken by Nova Scotian, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland privateers. Indeed, Halifax has good reason to remember the war fondly because when British troops occupied Castine, Maine, in 1814, they continued to collect the American customs duties, and, when the conflict ended, these funds were used to found Dalhousie College, now Dalhousie University, in that city. In a similar fashion, Lower Canada (the modern province of Québec), which, although frequently threatened, was only invaded twice by the enemy to the south, shared in the wartime economic boom created by defence spending. In Québec, as in the Maritimes, the War of 1812 is largely remembered as a prosperous time.

In Upper Canada (now Ontario), the westernmost part of British North America, the memory of the war was markedly different. American forces invaded the province seven times, large parts of it were under enemy occupation, the provincial capital was attacked twice, and the provincial legislative buildings were burned to the ground by the enemy. While the eastern part of Ontario, along the St. Lawrence River, had enjoyed a measure of wartime prosperity, much of the western portion, particularly the Niagara area, was a wasteland of burned villages, abandoned farms, and recently dug graves.

Although its wartime experience differed markedly from the other provinces of British North America, it was to be Ontario’s perspective of the War of 1812 that would largely dominate Canada’s national memory of the conflict. This was not only because Ontario eventually became the most populous and prosperous province in Canada but also because many of the textbooks used in English-speaking Canada were written by educators from Ontario.

The Ontario perspective was slow to develop, however, as the press in British North America in the early 1800s was tiny, and there was almost no local publishing industry. This was in contrast to the situation south of the border where numerous histories of the war appeared, some even before the ratification of peace. It was partly to counteract the spread of American books on the conflict that in 1832 David Thompson, a wartime veteran of the British army, published a “faithful and impartial account of the late war” as he believed the minds of Canadian youth “have been endangered by the poisoned shafts of designing malevolence which have everywhere discharged through the country, by the many erroneous accounts” from the United States. This was the first Canadian history of the war, and it was Thompson’s hope that his younger readers would “catch that patriotic flame which glowed with an unequalled resplendence in the bosoms of their fathers.”

Part of a series of articles titled The War of 1812 in Canadian Memory .

Last updated: April 2, 2015