This is an excerpt from Frank Norris' "Administrative History of Denali National Park" (2006, 2008).

“There must be an opportunity for the NPS to freshen peoples’ lives and offer a relief from the satiation of war.” Park Superintendent, Frank Been (1942)

Though not yet a state, the Alaska Territory served as both America’s home front and front line during World War II. While the Aleutian Islands became a battleground, war-weary soldiers took refuge in the breathtaking landscape beneath America’s tallest mountain.

After the December 7, 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. War Department’s Western Defense Command declared the Alaska Territory off-limits to tourist travel. Alaska’s location was strategically important now and its defenses were vulnerable. All travel to and from the territory was placed under military control for the duration of the war. For Mt. McKinley National Park, now known as Denali National Park, this meant a drop in visitors from 1,688 in 1941 to virtually nothing. With war rations keeping even Alaska residents at home, less than forty recorded non-military visitors entered the park between 1942 and 1945.

The military, meanwhile, recognized that the park could provide two major ways to aid the country’s overall war effort. First, Denali’s mountainous terrain and dangerously cold weather was an ideal site to test equipment for winter use. Second, at Denali and other national parks across the nation, military officials met with National Park Service leaders to repurpose vacant concession and park leisure facilities with rest and recuperation camps for furloughed warfighters.

Denali National Park’s Mount McKinley Hotel was high on their list. On-the-ground activity began in late December 1942, when Capt. George Hall of the Army’s Special Services Division arrived in the park “to study the situation and to formulate plans.” He stated that between 150 and 200 men would “be in constant attendance” and would be at the park on seven-day furloughs. Initial predictions called for the first men to arrive in February. Inevitable delays ensued, however; the 30-man opening crew did not arrive until March 27, and the Mount McKinley U.S. Army Recreation Camp did not officially open until April 10.

Thirty-three staff officers from Fort Richardson, along with Alaska’s Governor Gruening, attended an opening dinner that night, after which Acting Superintendent Grant Pearson read a welcoming speech from NPS Director Drury. Rangers showed motion pictures of the park’s wildlife. The following day the officers toured the park headquarters. Pearson later wrote that the military brass were “well pleased with the park in general and thought it an ideal place for the boys to spend their vacations after duty in the Aleutians and other Alaskan outposts.”

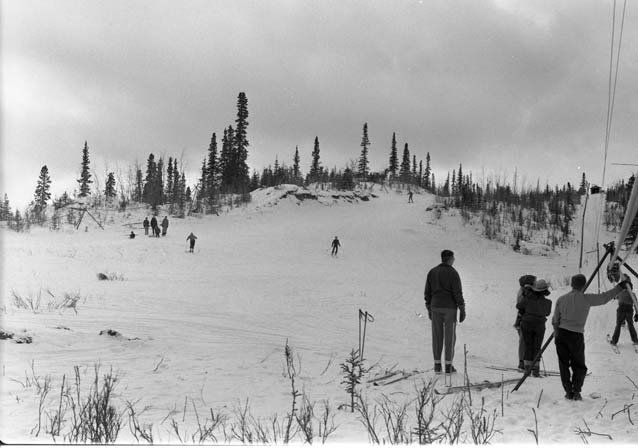

NPS Photo (1943) -- DENA 23004

Warfighters Enjoy First Class Treatment

Large numbers of soldiers began arriving soon after the opening festivities, and by the end of April 1943 the camp was an obvious success. As Acting Superintendent Pearson noted in a letter to Interior Secretary Ickes,

you will be pleased to learn that [the hotel] is being used for a splendid purpose. If you could see the soldiers as they enjoy the comforts of the hotel after a day’s jaunt in the Park you would realize that your efforts [in 1938 to improve the hotel] have not been in vain. They have only words of praise for those who made it possible for them to enjoy a respite from the fogs of the Aleutians, the damp cold of the Pacific and the chilling winds of interior Alaska

The hotel, indeed, proved its worth to thousands of furloughed men. At first, it was open only to white uniformed personnel, but in July 1943 it opened its doors to the first civilian War Department workers, and in February 1944 the first black troops visited the park. During the Recreation Camp’s two-year existence, the park played host to 11,324 visitors: 90 percent were members of the armed services, the remaining 10 percent civilian defense workers.

Park Service rangers, who had had years of experience speaking primarily to “teachers and people over 60 years old” did their best to ensure a memorable stay for the young men by giving illustrated talks and dog sled demonstrations, showing motion pictures, conducting guided walks, and answering thousands of questions; and beginning in June 1943, they even had a “little log cabin museum” at headquarters that proved highly popular. Those who stayed at the hotel during the winter months spent most if not all of their time within a mile or two of the hotel, but virtually all summertime visitors took trips out into the park in soldier-driven truck convoys. In 1943 a popular destination was Wonder Lake, where the Army set up a tent camp; those shelters deteriorated over the winter, however, so in 1944 military authorities repaired the “old tourist camp at Mount Eielson” (at Mile 66) for the soldiers’ use that summer.

The soldiers at the Mount McKinley U.S. Army Recreation Camp prepared a “Special Service Bulletin” that extolled the virtues of a McKinley furlough. In one article, for example, an enlisted man wrote that the 87-room hotel was

made to order for soldier vacations. … The glass enclosed lobby is strictly Fifth Avenue. It is beautifully designed, with modern furniture, big, thick rugs, comfortable easy chairs, oil paintings, shining chrome, and a hotel desk of Ritz Carlton caliber. … The game room is a knockout. It is one of the most completely equipped you ever saw. And the bedrooms will really slay you. Each has brand new twin beds and inner spring mattresses.

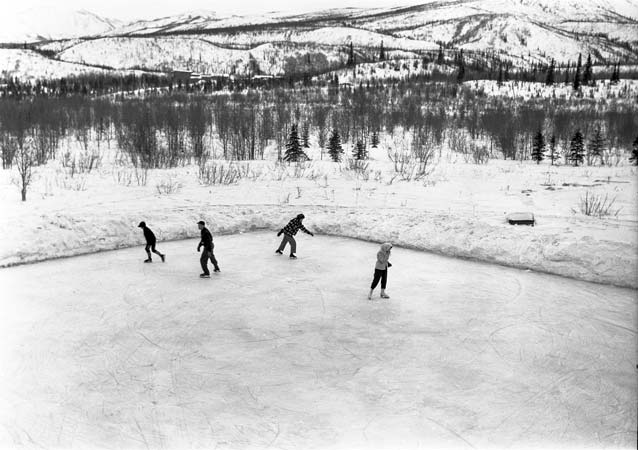

NPS Photo -- DENA 23984

He also noted that the hotel also offered a tap room (which was a soda fountain; guests were asked not to bring whiskey, which was prohibited), a barber shop, a recreation room, movie hall, library, lounge, and dining room. Other parts of the bulletin noted that soldiers were hurriedly preparing facilities for winter sports (ski runs, toboggan slides, and ice skating rinks), and come summer time, courts would be laid out for softball, volleyball, and tennis. A Park Service dog team would be available for both “mushing” and picture-taking; both Camp Savage and Camp Eielson would be open for camping opportunities, and there were chances galore for hiking, swimming (“if you’re really tough”), and fishing.

The following year new pastimes were added including archery, miniature golf, horseback riding from Savage River Camp, bicycling, horseshoe throwing, golfing from a short-range tee, ping pong, billiards, and dancing. Skating was offered at such far-flung venues as Horseshoe Lake and the Teklanika area, and during the winter of 1943-44, Army personnel rigged up a ski tow and warming hut at Mile 6 of the park road and offered skiing from December through April.

Entertainers from the U.S.O. performed, and by 1944 there were weekly stage shows at the McKinley Little Theatre. The park’s first-ever religious services were held on Easter Sunday in 1943, and there were even wedding bells to ring, in February 1945, when an Army Corporal and a Recreation Camp hostess (one of “five capable women hostesses” on duty) tied the knot.

Of Mutual Benefit

From the NPS’s point of view, hosting the thousands of soldiers was successful for several reasons. Not only did the visitors’ experiences provide “praise and good will” to the agency (according to Pearson), but the military helped in more tangible ways as well. Recognizing that the existing ranger staff was overtaxed trying to keep up their patrols and public contact work, the military approached the agency and asked what might be accomplished if four soldiers were assigned to assist with park duties. Pearson quickly replied and noted that they be assigned to do various critical construction jobs: repairing the telephone line from headquarters to Camp Eielson, constructing a first-ever telephone line from the headquarters to the hotel, improving the “ranger cabin at Savage,” overhauling the headquarters utility system, tearing down two abandoned log cabins at headquarters (which were in a “sad state of repair”), moving a small garage at headquarters, and various miscellaneous tasks.

NPS Photo

The Alaska Defense Command granted the request “in a decidedly satisfactory manner” (in Pearson’s words), and during the summer of 1943 it assigned Company F of the 176th Engineers to the task. The company spent the next several months on the job; they did the work “promptly and efficiently, in fact more was accomplished than was originally contemplated.”

The Army also improved access to the McKinley Station area by improving the old Morino airstrip at McKinley Park Station. The Morino airstrip was a 700-foot airstrip cleared out by local landowner Maurice Morino in the summer of 1932. It was used for emergency purposes for the remainder of the 1930s and but had fallen into disrepair until August 26, 1943. At that time, Army engineers arrived, moved into the old CCC camp, and improved the old Morino field by blading out a 3400-foot strip, deemed “large enough to permit the land of any type commercial land plane.” For the next 18 months, the airfield was used frequently; in August 1944, a record 105 passengers landed there, and beginning in January 1945, Alaska Airlines used the airstrip as a flag stop on its regular run between Anchorage and Fairbanks.

At War’s End

On February 2, 1945, military authorities told local officials that the Army Recreation Camp had to cease operations on March 1. This was “in accordance with general orders that all unnecessary activities of the army be discontinued at once.” This should have come as no surprise to those who were in charge of the camp; by this time, it had been almost 18 months since Alaska military forces had seen combat, and as a result, troop strength in Alaska had fallen from more than 150,000 in 1943 to just 60,000 in 1945.

Authorities decided to close the camp because too many soldiers had been shipped out of Alaska to warrant its continued operation. On March 1, all members of the camp staff and part of its detachment departed for Anchorage. Twenty members of the detachment stayed behind to close the hotel, but they too were soon gone.

Although the hotel was no longer operating as a military recreation camp, World War II was still raging in both the Pacific and European theatres. As a result, access to and from Alaska was still closely monitored, and recreational tourism to the park—except by civilians residing in the territory—was still prohibited. Those conditions would not change until well after V-J Day in August 1945.

As a result, visitation to Mount McKinley National Park during the summer of 1945 was largely a repeat of what the park had experienced in 1942. Summertime visitors in 1945, therefore, included groups of military officers, Anchorage business men, and scattered Alaska-based tourists. That number was augmented by two groups of Congressmen who visited in August and made trips out the park road. (They overnighted either at park headquarters or at the Wonder Lake Ranger Station and were served meals prepared by the superintendent and his staff.) In addition, railroad and steamship-company officials made periodic visits to the park “to study tourist travel to McKinley Park after the war.”

Otto Ohlson, the Alaska Railroad’s general manager, released an optimistic statement to the newspapers regarding the carrier’s postwar plans, which included “one-day train service between the coast and Fairbanks … an addition to the McKinley Park Hotel and the erection of a lodge and cabins at Wonder Lake to care for the inevitable tourist traffic; and most important of all, a reduction in rail rates.” Both he and others, however, knew that all of those plans depended on a strong upsurge in visitation and, just as important, on a Congress willing to loosen its purse strings for Alaska projects. In the meantime, all they could do was wait. No one knew just how tourism would look during the postwar years, and how the NPS managers would respond to these and other challenges that would soon be sent their way.

The Mt. McKinley U.S. Army Recreation Camp would come to life again, albeit briefly, during the Korean War.

References

For all footnotes and references related to this excerpt, please see pages 114-119 of Crown Jewel of the North: An Administrative History of Denali National Park (Volume 1), published in 2006.

Last updated: October 26, 2021