Last updated: March 6, 2023

Article

The Archeology of Abalones: Chinese and Japanese Fishing Camps in Channel Islands National Park

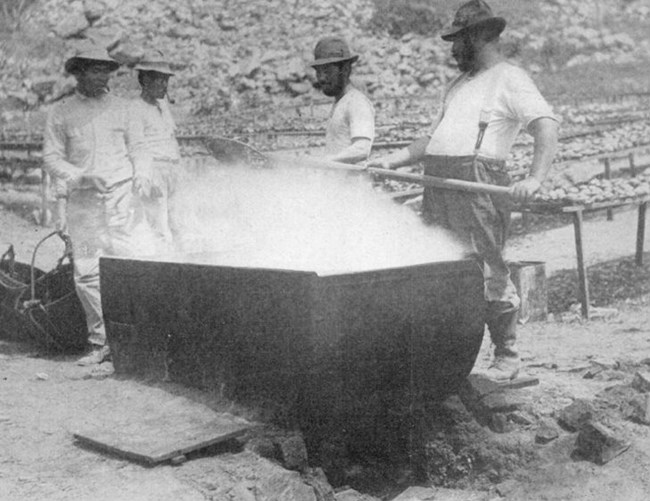

Edwards, Fig. 2

The Channel Islands National Park off the California coast contains areas of Santa Barbara, Anacapa, Santa Cruz, San Miguel, and Santa Rosa Islands. Over the past 13,000 years, various groups have occupied these areas. The first were Native Americans, specifically the Chumash people and their ancestors, who lived in various villages around three of the islands. However, with European colonization in the late 18th-century came the introduction of diseases, a declining food supply, and the establishment of Catholic missions, all of which led to the removal of Native peoples to the mainland. By the 1820's, all of the island villages were abandoned.

Social discrimination, codified in various federal laws passed in the late 1800's, gradually pushed Chinese individuals out of their prominent place in the abalone industry. Their vacancies were then filled by Japanese and Euro-American individuals who introduced new harvesting methods. Prominent among these was the Japanese hard-hat diving suit. Japanese divers continued to move around the Channel Islands, sometimes occupying abandoned Chinese camps.

While few historical accounts exist detailing the daily experiences of 19-20th century Chinese and Japanese immigrants on the islands, archeological materials can help uncover their stories. Multiple surveys and excavations were carried out on the islands and several have located remnants of the once-flourishing abalone industry.

Archeological features included abalone shell scatters, stone windbreaks, wooden and stone drying slabs, and campsite hearths. The hearths were used for cooking, boiling abalone meat, and processing blubber (Braje et al., 128). Notably, some were made in a unique “hairpin” shape. This hearth type has been located on Chinese campsites both on the Channel Islands and California mainland and may be a sign of a shared cultural tradition.

Braje et al., Figs. 5 and 6

Archeologists also excavated many artifacts at the campsites, including Chinese and Japanese ceramic sherds, glass bottles, and personal items such as carved sea lion teeth, buttons, smoking pipes, and opium boxes. Some of these artifacts are diagnostic in that they help archeologists narrow down when the sites were occupied. For instance, it is likely that this blue-and-white Japanese sherd was brought to the islands after the late 1800’s. The fact that it was found on an earlier Chinese campsite is evidence of how these camp areas were reused through time.

Taken together, these artifacts and features help understand how Chinese and Japanese fishermen lived and worked every day on the Channel Islands. Hearths, drying slabs, and abalone shell scatters are direct remnants of a once-thriving industry, while lost buttons, broken pipes, and scattered ceramic sherds are reminders of the individuals who made it possible.

Resources

Braje, Todd J. and Jon M. Erlandson. Historical Abalone Fishers of San Miguel Island, California. In Proceedings of the Society for California Archaeology 19 (2006):21-26.Braje, Todd J., Julia G. Costello, Jon M. Erlandson, and Robert DeLong. Of Seals, Sea Lions, and Abalone: The Archaeology of an Historical Multiethnic Base Camp on San Miguel Island, California. In Historical Archaeology 48(2): 122-142.

Edwards, Charles Lincoln. The Abalone Industry in California. In Fish Bulletin 1 (1913): 5-15.

National Park Service. Chinese Abalone Fishermen.

National Park Service. California: Channel Islands National Park.

National Park Service. The History of Chinese Abalone Fishermen in California video.