Last updated: December 1, 2018

Article

Abraham Lincoln's Boyhood in Indiana 1816 to 1830

Lloyd Ostendorf

In much of the work his young and capable son assisted Thomas. As he grew older, Abraham increased in his skill with the plow and, especially, the axe. In fact, in later life he described how he “…was almost constantly handling that most useful instrument…” to combat the “…trees and bogs and grubs…” of the “unbroken wilderness” that was Indiana in the early 19th century.

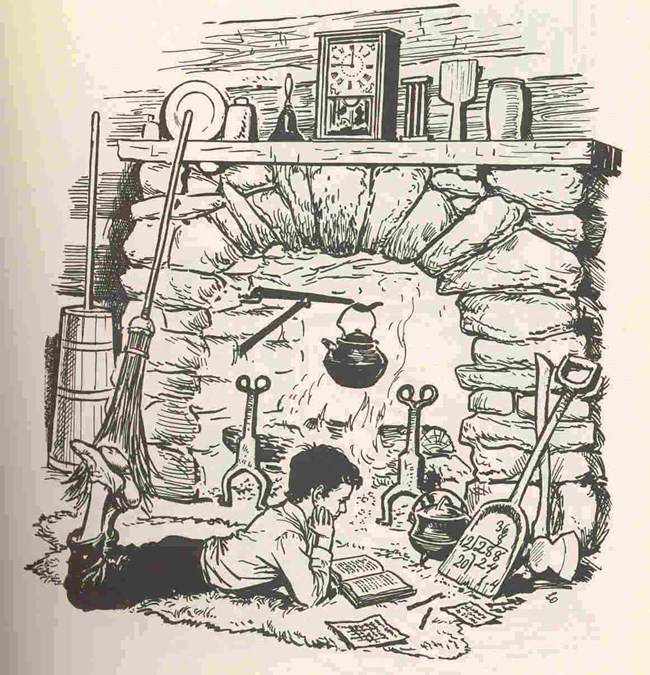

The demands of life on the frontier left little time for young Abraham to attend school. As he later recalled, his education was acquired “by littles” and the total “…did not amount to one year.” But despite the limitations he faced, his parents encouraged him in very way possible. Soon, his eyes were opened to the joy of books and the wonders of reading and he became a voracious reader. At the age of 11 he read Parson Weems’ Life of Washington. He followed it with Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography, Robinson Crusoe, and The Arabian Nights. He could often be seen carrying a book, as well as his axe. For Abraham Lincoln, to get books and read them was “the main thing.”

Life was generally good for the Lincoln’s during their first couple of years in Indiana, but like many pioneer families they did not escape their share of tragedy. In October 1818, when Abraham was nine years old, his mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln, died of the milk sickness. The scourge of the frontier, milk sickness resulted when a person drank the contaminated milk of a cow infected with the toxin from the white snakeroot plant. Nancy had gone to nurse and comfort her ill neighbors and became herself a victim of the dreaded disease. For young Abraham it was a tragic blow. His mother had been a guiding force in his life, encouraging him to read and explore the world through books. His feelings for her were still strong some 40 years later when he said, “All that I am or hope to be, I owe to my angel mother.”

Sadly, Thomas and Abraham whipsawed logs into planks, and with wooden pegs, they fastened the boards together into a coffin for the beloved with and mother. She was buried on a wooded hill south of the cabin.

The family keenly felt Nancy’s absence as young Sarah and Abraham were now without a mother and Thomas without a wife. This loneliness led Thomas in 1819 to return to Kentucky in search of a new wife. He found her in Sarah Bush Johnston, a widow with three children. Thomas chose well for the cheerful and orderly Sarah proved to be a kind stepmother who reared Abraham and Sarah as her own. Under her guidance, the two families became one.

The remainder of his years in Indiana were adventurous ones for Abraham Lincoln. He continued to grow and by the time he was 19, he stood six foot four. He could wrestle with the best and local people remembered that he could lift more weight and drive an axe deeper than any man around.

In 1828, he was hired by James Gentry, the richest man in the community, to accompany his son Allen to New Orleans in a flatboat loaded with produce. While there, Lincoln witnessed a slave auction on the docks. It was a sight that greatly disturbed him and the impression it made was a strong and lasting one.

Abraham continued to work intermittently for Gentry at his store. He also began to take an interest in politics. The Gentry store was often a gathering place for local residents and there Abraham listened as a number of political views were aired. At home was more talk of politics and he began to form his own opinions. With a keen mind and a gifted knowledge of words he was able to make his own contributions to the lively discussions.

Another job that Abraham had during his teenage years was operating a ferryboat service across the mouth of the Anderson River. In his spare time he built a scow to take passengers out to the steamers on the Ohio. One day he rowed out two men and placed them aboard with their trunks. To his surprise each threw him a silver half-dollar. “I could scarcely credit,” he said, “that I, a poor boy, had earned a dollar in less than a day.”

Although profitable, his business venture also led to one of his first encounters with the legal system. Two brothers, who held the ferry rights across the Ohio between Kentucky and Indiana, charged Lincoln with encroaching on their jurisdiction. Kentucky law, in such cases, provided for the violator to be fined. But, because he did not carry his passengers all the way across the river but only to the steamboats, the judge ruled that Lincoln had not violated the law and dismissed the charge.

By all accounts the Lincolns prospered in Indiana, but in 1830 Thomas decided to move to Illinois. Relatives there had described the soil as rich and productive and that milk sickness, which threatened to break out again in the Little Pigeon community, did not exist. With that news, Thomas sold his property and left the state.

Abraham Lincoln lived in Indiana for 14 years, from the age of 7 to the age of 21. During that time he had grown physically and mentally. With his hands and his back, he had helped carve a farm and home out of the wilderness. With his mind, he had begun to explore the world of books and knowledge. He had experienced adventure and he had known deep personal loss. The death of his mother in 1818 and the death of his beloved sister, Sarah in 1828, left deep emotional scars. But all those experiences helped make him into the man that he became.