Last updated: December 14, 2020

Article

“An Outrageous, Barbarous and Deadly Attack”: Racist Violence in the Midwest before the Civil War

One of their number, Major Wilkerson, was made their leader; and never did man exhibit on the field of danger greater coolness, skill, and bravery, than this champion of his people’s cause. A negro himself, he fought in self-defence [sic], and to maintain his own rights as well as those of the people whom he led.[1]

Library of Congress

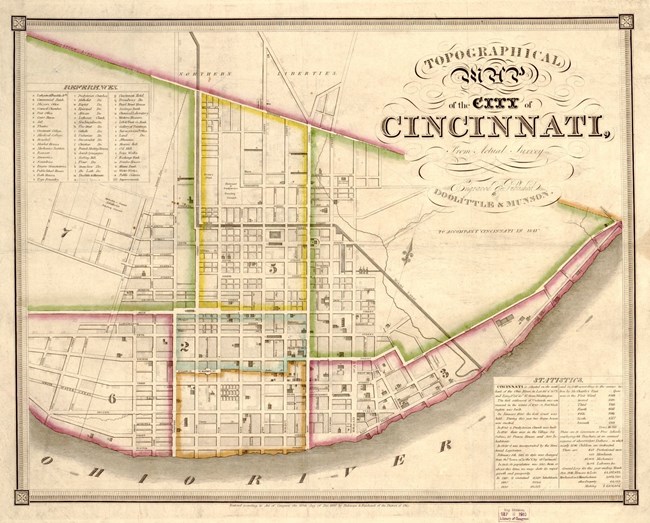

“Major” James Wilkerson had come a long way in order to be in Cincinnati. It was a hot night late in the summer of 1841, twenty years before the Civil War, and Wilkerson and the other African American men around him were preparing to defend themselves in battle. They had come to the rooftops and alleyways of their neighborhood to protect it from an attack they knew was coming soon.

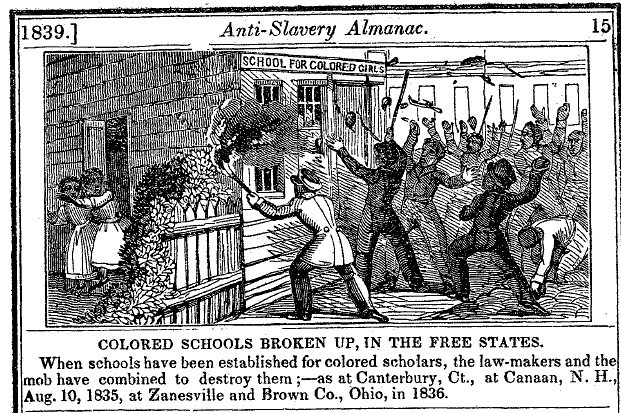

These confrontations are often referred to as riots, but in reality they were acts of racist violence waged by white people against African Americans (and the few white people who supported them). By the 1830s, the free African American residents of almost every city and rural community, north of the Mason Dixon had experienced tragedy – the burning of a school, a church, or an entire neighborhood. The attacks went beyond buildings, and included violence against Black men, women and children, resulting in injury and death.

Samuel J. May Anti-Slavery Collection

Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

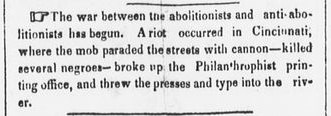

In addition to these atrocities, the majority of white people in the Midwest were also turning their backs on the best ideals of liberty and equality fought for in the American Revolution – a Revolutionary War that African American patriots had fought and died in. Across the Midwest states were reversing constitutions and creating laws stealing the right to vote from Black men, as well as the right to congregate and the right to a trial by jury. There were even attacks on freedom of speech, with the newspaper offices and presses of Black and white abolitionists attacked, and their mail and petitions blocked, denied and “gagged” by the federal government.

This was not caused because of some growing radicalization and agitation of abolitionists, or because of African Americans’ immorality and criminality. This violence, which was often coupled with racist laws, was a backlash against African Americans beginning to gain their rights and very visibly thriving in urban and rural areas. This period saw a migration of tens of thousands of free African Americans moving to the Midwest, creating highly visible and successful farms and communities across Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin.

Dr. Edward Abdy, a British professor, traveled to some of these communities in this region in the early 1830s. He recorded his experiences in the book Journal of a Residence and Tour in the United States. During his stay with a family of African American Underground Railroad Operatives near Madison, Indiana, he was told that “while they were clearing their farms of the timber [in the 1810s], they were unmolested; but now that they have got the land into a good state of cultivation, and are rising in the world, the avarice of the white man casts a greedy eye on their luxuriant crops; and his pride is offended at the decent appearance of their sons and daughters.”

Like the family in Madison, Indiana, James Wilkerson and other African Americans in Cincinnati, had achieved much Wilkerson was born into bondage in Virginia (date unknown), enslaved by his own white kin. He attempted to rebel against his bondage by seeking freedom, but was constantly captured and brought back. Finally, his white relatives decided that they wanted to be rid of him, and separated him from his mother and all he had known, selling him “down river” at the dreaded slave markets of New Orleans. But even after he was sold, Wilkerson refused to allow his dream of freedom to die. He worked extra hours while enslaved to earn the money to purchase himself. As soon as he was free, he worked to earn the money to purchase his mother’s freedom. While enslaved, he had illegally learned to read as a teenager, and once free he decided to become a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. He served as a missionary, establishing churches and schools across the Old Northwest frontier.

Now the freedom he had worked so hard for was being threatened, so he and the men around him on the rooftops of their homes and businesses in Cincinnati were determined to defend themselves and their community. There had been two other attacks already in Cincinnati, one in 1829 and one in 1836. Wilkerson and the men he had organized knew another attack was coming. There had been warnings, there always were. These were not secret attacks, they were well organized, with white politicians, lawmen, lawyers, pastors and newspaper editors organizing rallies, printing articles and even posters to raise the violent hatred of other white people. These printed materials provided information on when people were supposed to gather and march on the African American communities, and warned African Americans that an attack was coming.

Library of Congress

And when these attacks occurred, whether in Cincinnati or dozens of cities across the Midwest, they were rarely condemned. The white perpetrators were rarely punished. Black communities, still reeling from the loss of property and life faced further injustice including the loss of what rights they had once held. In Cincinnati, after Wilkerson and his men managed to successfully safeguard their homes and families from white attackers that night in September 1841, the mayor ordered that all Black men in the city be thrown into jail, if they weren’t shot first.

Wilkerson managed to survive this incident, but had to keep his involvement in his community’s defense a secret. He remained in Cincinnati where he continued his work in the struggle for freedom, as an Underground Railroad operative, as well as supporting the work of other Black men and women to assist freedom seekers.

While histories of the Underground Railroad in the Midwest continue to be of interest to many today, stories of African American resistance to slavery as well as racism in the region, still go largely unknown, as does the history of the racist violence that was common across the Midwest before the Civil War. Academic historians have long favored a narrative that focused on the white leaders of the Underground Railroad in this region, instead of the much more sinister movement to destroy the rights and lives of Black people during this period. This trope is tied to a troubling myth that racism was a product of the South, but racism in the North arose long before the end of slavery and it was homegrown and potent.

The truth of this violence, as well as the Black men and women who resisted it, deserves to be better known. As Wilkerson wrote in 1859, of his efforts to further the causes of liberty and equality, “May he not say in truth that he has fought the good fight?”

Anna-Lisa Cox is an award-winning American historian whose original research underpinned two exhibits at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. Her writing has been featured in a number of publications including The Washington Post, Lapham’s Quarterly and The New York Times. Her newest book The Bone and Sinew of the Land was honored by the Smithsonian Magazine as one of the best history books of 2018, Professor Henry Louise Gates Jr. praised it for being “a revelation of primary historical research that is written with the beauty and empathic powers of a novel.” Dr. Cox is currently a Non-Resident Fellow at Harvard University’s Hutchins Center for African and African American Research.

Footnotes

This title comes from a reminiscence by John Mercer Langston (1829-1897) who was a youth living in Cincinnati at the time of the riot. See John Mercer Langston, From the Virginia plantation to the national capitol; or, The first and only Negro representative in Congress from the Old Dominion (Hartford, CT: American Publishing Co., 1894), 63.

[1] Langston, From the Virginia plantation to the national capitol, 64.