Yesterday, December 19, was the centennial of the Raker Act, the bill that allowed the building of a dam in the Hetch Hetchy Valley. The Raker Act was highly controversial and the points of view that were argued on both sides of the controversy are valuable perspectives that are still relevant today. The debate pitted the needs of San Francisco, a rapidly growing city trying to find a large and reliable source of water, against the proponents of a newly formed Yosemite National Park. This event helped to further refine the idea of national parks, an idea that began in Yosemite nearly 50 years before.

Yesterday, December 19, was the centennial of the Raker Act, the bill that allowed the building of a dam in the Hetch Hetchy Valley. The Raker Act was highly controversial and the points of view that were argued on both sides of the controversy are valuable perspectives that are still relevant today. The debate pitted the needs of San Francisco, a rapidly growing city trying to find a large and reliable source of water, against the proponents of a newly formed Yosemite National Park. This event helped to further refine the idea of national parks, an idea that began in Yosemite nearly 50 years before.

June 30, 1864, is the day that Abraham Lincoln signed the Yosemite Grant, an act of Congress that permanently set aside the first public land in our country. When Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias were given to the State of California to manage as public parks, the core of the national park idea was established. In 1890, a larger park, closer to the size we know today, was established around the original Yosemite Grant, to be managed by the federal government.

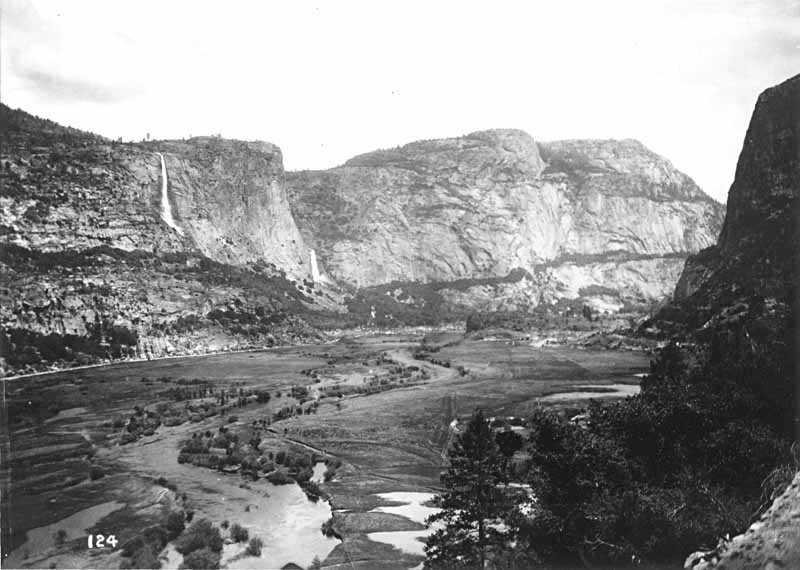

By this time, the geographically isolated San Francisco had begun searching for potential sources of water for its growing population. City politicians had their eyes on the Tuolumne watershed, which was now within the new Yosemite National Park. The water there was of the purest quality, coming from melting snow in the mountains and flowing through granite basins without collecting much silt. Because the watershed was at such high elevation, the city would also have a bountiful source of hydropower.

After failing to obtain water rights within the national park for several years, San Francisco endured a terrible earthquake in 1906. The resulting fires leveled much of the city and made headlines around the country. With the emotional weight of burning buildings fresh in the public’s mind, the case for providing the city with water suddenly became stronger. 1906 was a big year for Yosemite as well, marking the official union of Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove with the greater park into one federally controlled national park. At the time, federal troops were stationed in Yosemite Valley to enforce the park regulations because there was no national agency to do the job.

Certainly there were passionate voices on both sides of the issue, focusing the nation’s attention on this remote mountain valley. Local newspapers called the bill’s opponents “a crowd of nature lovers and fakers, who are waging a sentimental campaign to preserve the Hetch Hetchy Valley as a public playground, a purpose for which it has never been used.” Gifford Pinchot, the former Chief Forester of the US Forest Service, testified before Congress that the creation of a reservoir in the valley was “the greatest good for the greatest number” in reference to not only the water use but the increased accessibility that the development would certainly provide. John Muir, who led the opposition, wrote beautifully about the valley, calling it “one of Nature's rarest and most precious mountain temples.” He appealed to the nation, asking what else might be at stake if we allowed the creation of a “water tank” in this national park.

Armed with powerful political allies and an equally powerful publicity campaign, San Francisco pushed the legislation forward. Even Muir conceded that he did not want to deny the hundreds of thousands of people in the city water, but that he hoped there could be an alternative to developing the national park. In the end, the Raker Act became law on December 19, 1913 and San Francisco celebrated its new water security, a pristine watershed preserved in a national park.

This may have marked the end of the battle for John Muir, but it was only the beginning of a new era for the parks. For the first time, our country had to decide what the designation of a national park actually meant. As people tried to answer that question for themselves, the public disapproval that was generated after the bill’s passage was one of the driving forces behind the creation of the National Park Service. Within three years, Congress had passed the Organic Act, formally defining the parks and creating a new federal agency, the National Park Service, with a mission “…to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.” Now the national parks would be managed as a more cohesive national system and not be as vulnerable to local pressures for development.

The grassroots organization of environmental activism used by Muir became a model for future environmentalists to appeal to individuals to influence their elected officials. Many subsequent proposals for development in our national parks have been defeated by citizen activists inspired by calls to remember Hetch Hetchy. This call reminds us that once you have created a national park, it doesn’t mean it is protected forever. Our special places need heroes to continue to advocate on their behalf and all of these champions can harken back to Hetch Hetchy as a martyr to the cause.

The idea of the national parks was born in Yosemite, so in a way it is fitting that one of its biggest growing pains also occurred here. Today the Hetch Hetchy Valley is under 300 feet of water and while we may no longer be able to see the valley as it once was, our view has merely been changed. Like light shining through a prism, our views today must reflect the colorful variety of perspectives passed down through history. We may see a scenic mountain landscape reflecting on the surface of the water. We may see a community of 2.6 million people that thrive on one of the finest drinking water supplies in the country. We may see a system of roads and trails built and maintained to provide access to a remote mountain wilderness. We may see the beginning of the modern environmentalist movement and a reminder of what the national parks stand for. The next time you are in Yosemite, take a drive to Hetch Hetchy and see what your view is like.