NPS The full study will be available online soon, but the park wants to make a few notable excerpts available now.

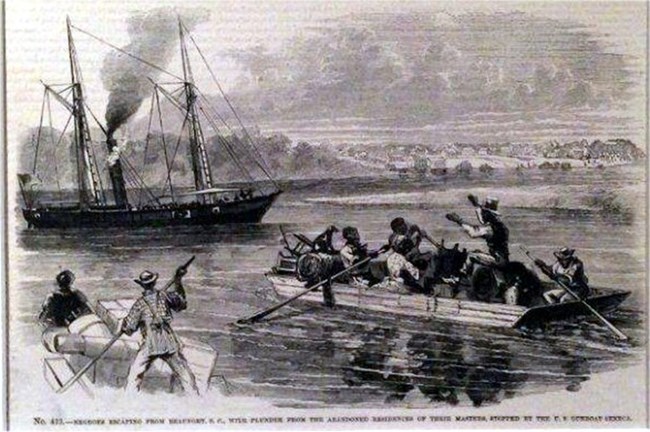

Negroes escaping from Beaufort, S.C., with plunder from the abandoned residences of these masters, stopped by U.S. Gunboat Seneca/The New York Public Library Digital Collection Introduction"During the American Civil War (1861-1865), areas in and around TIMU developed into significant emancipation sites as many local freedom seekers fled enslavement and found emancipation with the assistance of US Army and Navy personnel. Many enslaved men in and around TIMU eventually enlisted in the US military. Most entered a United States Colored Infantry (USCI) Regiment, while others joined the US Navy. Regardless of where they served, these Black men viewed their enlistment as a personal and collective transformative event. Individually, Black soldiers wanted to play a part in securing slavery’s ultimate destruction. Military service provided a means for Black men to publicly demonstrate their masculine pride and restore a part of their humanity that had been assaulted during enslavement. Black soldiers believed that military service would make their case for creating a post-emancipation American society founded on human equality and civil rights. Through the individual actions of Black men such as February Christopher Francis Shaw, Albert Sammis, George Floyd, Pablo Rogers, Elias Lottery, Alonzo Phillips, and many other USCI veterans who originated from areas in and around TIMU, freed people laid claim to their rights as Americans and sought to uplift their race to a position of equal footing among all of humanity. These USCI veterans came from locales scattered across the St. Johns River, including Mayport Mills, Pilot Town, Fort George Island, St. Johns Bluff, Yellow Bluff, Strawberry Plantation, Clapboard Creek, Greenfield Peninsula, and more."...Sammis/Kingsley Family and the Civil War"John Sammis, New York native and carpenter, came to Florida in 1829 to work for Zephaniah Kingsley. Almost immediately Sammis developed a relationship with Zephaniah and Anna’s daughter Mary. In 1830, John Sammis and Mary Kingsley married. As the daughter of an African born mother, Mary Kingsley Sammis was a woman of color. During the 1830s, Sammis developed extensive business connections across northeast Florida with merchant operations in Baldwin, Fernandina, and Jacksonville. In 1839, Sammis purchased Strawberry Plantation on the south bank of the St. Johns River, the location of the modern-day Arlington neighborhood of Jacksonville.94 He opposed secession and welcomed federal occupation forces into the region. When federal forces briefly occupied Jacksonville in March of 1862, Sammis joined a convention of local Unionists who passed a resolution pledging the city’s loyalty to the United States in defiance of Florida’s secession ordinance. When federal forces hastily evacuated Jacksonville, Sammis and his family, both free and enslaved, boarded naval vessels to escape the feared retribution of the returning Confederates. After spending time in New York City, Washington, DC, and Port Royal, Sammis returned to Fernandina to oversee his growing mercantile business. Sammis likely lobbied federal officials to appoint him to the Florida Direct Tax Commission—a role that would provide ample opportunities to enhance his personal fortune by acquiring seized Confederate assets at below market prices.95"First US Occupation of Jacksonville(March 12, 1862-April 9, 1862) Freedom Seekers and the Navy"The US Navy and freed people developed a mutually beneficial relationship. Freed people often commandeered small boats or swam to reach the US Navy that patrolled the St. Johns River. US Navy vessels brought freedom seekers onto their ships because freed people often provided valuable information about CSA activities. However, during the first US military occupation of Jacksonville, American commanders sought to either preserve or promote Unionist sentiments in the region by protecting the property rights of enslavers who had remained loyal to the federal government. Emancipation was not among the military’s objectives. Nonetheless, many freedom seekers who successfully claimed that their enslavers had supported the Confederacy were either carried by US Navy vessels to freed people colonies in St. Simons Island, Georgia, and Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, or transported to the mouth of the St. Johns River where freed people camps were forming at Mayport Mills. Federal policy, however, did not curtail the desire of freedom seekers to flee to federal naval ships.expecting their newfound liberation to be recognized and protected. What freedom seekers encountered when they reached federal lines often depended on a particular US soldier’s or sailor’s racial prejudices and abolitionist views. Although the federal policy intended to create a standard response to freedom seeker demands, many soldiers and sailors ignored their orders and embraced Black calls for emancipation."

Cosmo"Cosmo is a predominately Black historic community located adjacent to the TIMU visitor center on the south bank of the St. Johns River near St. Johns Bluff. According to the Cosmo Historical Preservation Association, “The Cosmo Community is a community isolated from the City of Jacksonville, Florida by the St. Johns River where Cosmo . . . residents carved out their existence.” Contemporary residents recall that the Cosmo Community formed along a road that led from Fulton to St. Augustine. Today, most of the Cosmo community is located on Fort Caroline Road. Alexander Memorial African Methodist Episcopal and Palm Spring Cemetery, two Cosmo community landmarks, are located on Fort Caroline Road near the TIMU visitor center at St. Johns Bluff. Prior to the late 1960s, the dirt road that ran through the Cosmo community was known as Route 1 and not Fort Caroline Road. That historic dirt road was paved and named Fort Caroline Road in the late 1950s during a period when Jacksonville began to consolidate the scattered neighborhoods into one centralized city. At that time, many Cosmo residents lost their land to developers who constructed many of the subdivision communities and large single family housing that can be seen up and down the modern-day Fort Caroline Road. Cosmo’s boundaries appeared to be fluid and interconnected with other nearby Black communities. According to locals, “Residents of Cosmo traveled on a foot path to another Black community located near the Mt. Zion United Methodist Church (then Methodist Episcopal Church) near Lone Star and Millcreek Roads. [Cosmo residents] lived in a tight knit family oriented community where fishing and farming was not a stranger.” Many of the Black households in this area shared a common ancestor, James Bartley a freed man from South Carolina. Bartley, however, does not appear on any USCI muster rolls.NPS has recognized Cosmo and Fulton as part of the regional Gullah Geechee Heritage Corridor that canvases the Atlantic seaboard from southeast North Carolina to northeast Florida. At least six Gullah Geechee communities have been recognized in the Jacksonville area, including: Brooklyn, Cosmo, Eastside, LaVilla, Pine Forest, and West Lewisville." Benjamin White, 21st USCI"In many ways, Benjamin White is a representative example of a typical late nineteenth century resident of Cosmo. Approximately, 60 percent of the community was born in South Carolina. White was born around 1830 in Darlington County, South Carolina. He spent over thirty years working as an enslaved laborer on one of the county’s large cotton plantations. No records exist that document White’s journey to emancipation. Somehow by the late summer of 1864, White had fled bondage and traveled nearly 200 miles south to reach Hilton Head Island, South Carolina. A military recruiter from Vermont urged White to voluntarily enlist so that his service could be counted toward that state’s enlistment quotas. Since most freedmen came from Confederate states, military recruiters in most US states tried to encourage freed people to enlist on behalf of their state and thus help reduce the number of military aged draft eligible White men who would be required to serve. White received an additional $100 from Vermont when he enlisted as compensation for this services. In total, White received $200 during his enlistment. White was assigned to the 21st USCI and immediately joined the regiment near Charleston. For several months, White served guard duty on Morris Island where he endured hot humid days followed by cool crisp nights. Despite the horrid conditions, White appears to have remained in good health throughout his military service. He joined the regiment when it captured Charleston in February 1865. Like other Black soldiers, White camped at the Citadel and helped patrol the city to ward off Confederate guerrillas and criminals who wished to loot the city. White remained with the regiment in Charleston until he was mustered out of service in April 1866.How White came to live in Cosmo is unknown. By 1866, White had relocated to the area that became Cosmo. He and his wife welcomed the arrival of a newborn son, William, that year in Cosmo. Interestingly, White identified himself as a landowner in the 1870 US Census with approximately $100 in real estate. No record of White’s property deed could be located in the Duval County, Florida, courthouse. Nor did local county records include any mention of White in any court records. Nonetheless, White’s descendants recall that Benjamin owned considerable property in Cosmo. It does appear that White’s first wife, whose name is unknown, died sometime between 1866 and 1870. Around 1871, White remarried a widower named Eliza. Together the couple had at least four children." Robert Anderson, 34th USCI"Like Benjamin White, few sources remain that shed light on the life of USCI veteran and Cosmo resident Robert Anderson. Born in the sea islands of South Carolina around 1830, Anderson had worked as an enslaved carpenter prior to emancipation. After enlisting in the 34th USCI in Beaufort, South Carolina, in March 1863, Anderson received a promotion to the rank of corporal. As a non-commissioned officer in a regiment commanded exclusively by White commissioned officers, Anderson and other Black corporals and sergeants played critical roles in maintaining unit discipline and communications. After the Confederacy’s surrender, Anderson’s unit was assigned to Jacksonville, Florida, from October 1865 to January 1866. After mustering out of service, Anderson remained in Duval County. In 1870, he worked at a local lumber mill and owned $200 in real estate. Despite his military service and postwar success as a landowning laborer, Anderson never learned to read or write. Anderson is buried in the Lone Star Cemetery."More Individual StoriesJames Eulin"The life of James Eulin is a unique story of an enslaved individual who, after escaping slavery, served in both the US Navy and Army, and got married during his service. Unfortunately, his unique experiences ended too soon as Eulin, like many Civil War soldiers, died of disease while still in the service. James Eulin was born around 1839 on Talbot Island, Florida, and lived his early life enslaved by John Houston. His mother, Pattie Smith, lived on Talbot Island and enslaved by the Houston family for much of, if not all of, her life. Not much is known about James’ father except his name, Sam Eulin. Given that when James enlisted, the army recruiter identified him as black complexion, it is likely that James’ father was an enslaved Black. During this time, Pattie Smith also had another child, Jeff Houston, likely the son of John Houston. While interracial relations were common in this area of Florida and in many areas of the South, it is important to note the complexity of these relationships and, more often than not, the result of sexual violence than consensual relationships. The few bits of information about James’ early live give insight into the increasingly intergenerational nature of slavery in the 1800s and the damage that enslavement and the practice of slavery had on enslaved Black families. During his childhood, John Houston gave James to one of his sons, D. B. Houston, and Pattie to another son. Despite being enslaved now by two separate men, James and Pattie fortunately managed to stay together on the same plantation. Black families faced the constant threat of separation as the result of the slave trade, or as with this case, inheritance; therefore making James and Pattie’s a rarity... In James’ case, during enslavement he made two relationships that proved valuable later in life. Henry Hannahan, whom James would later serve under in the 21st USCI, visited the Houston plantation before the war and established a relationship with James. Stephen Wright, another enslaved individual who knew and lived with James on the Houston plantation, later served with James during the war. The value of these relationships extended to his mother as well as she used both men as witnesses when filing for a federal pension later in life.Two years after the start of the war, James and his mother gained their freedom. The exact circumstances surrounding their emancipation are unclear. It is possible that the Houston’s granted them their freedom or perhaps self-emancipated when the Houston's possibly abandoned their plantation as US armies approached the area. Through the actions of self- emancipating Blacks, the US Naval outpost at Fernandina became a large contraband camp. The journey from Talbot Island to Fernandina is less than 20 miles; however, over that distance, there are numerous wetlands, the St. Marys River, and other geographic obstacles. James and his mother may have escaped on foot using hidden trails used by other enslaved individuals; it is also possible that they managed to get aboard a passing U.S. vessel and sailed to Fernandina... On one hand, the camps stood as beacons of freedom where formerly enslaved individuals could find freedom and a degree of protect. On the other hand, the formerly enslaved found themselves subject to the federal military and federal officials, making that imagined freedom a stark reality. Freedmen and women like James and his mother still faced the threat of Confederate raids and now had to strategize how to sustain themselves in this new reality. Military service provided a potential avenue for stability for freedmen. Service in the military offered men the prospect of financial stability, valuable experience, an opportunity to overthrow slavery, among many others. However, as appealing as the decision to enlist could be, it did come with some drawbacks, namely the effect that a male provider leaving a family would have on the family’s situation. James and his mother experienced this drawback when James enlisted in the US Navy. According to Stephen Wright, Pattie cried “like a baby because he was going. He was her only support and took care of her in slavery times.” That decision, while likely necessary, proved a difficult one for Pattie. The tears she shed upon his departure provided a stark reminder of the impact military service had on Black families specifically. Surviving accounts provide little information about Eulin’s naval service. Historical research show that as opposed to service in the Army, where the Army placed Black enlistees in the segregated USCI, no such official segregation existed abroad US vessels. The US Navy in addition to desegregated ships, promoted a near colorblind policy regarding military discipline, pay, and promotion. While the implementation of these colorblind policies could vary depending on the ship captain and instances of racial discrimination from individual White sailors still existed, the US Navy provided a relatively egalitarian experience for Black sailors. In addition to these insights, historical research demonstrates that the daily life of sailors in the common blockade duty involved mostly work parties, moving supplies between boats, and performing drills. Frequently, many of the more physical tasks assigned to Black sailors, but once again this varied depending on the ship and the captain in charge. There are notable instances of naval combat in which Black sailors performed honorably, including the multiple Black sailors who received Medals of Honor for their acts of heroism. However, those instances represent a minority of the broader experiences of Black sailors. On August 7, 1864, while in Hilton Head, South Carolina, James decided to forego his naval service and enlist in the USCI. Surviving documentation does not provide the reasoning for this switch. According to his enlistment papers, US Army mustered James into Company F of the 21st regiment. His enlistment papers put James at 25 years old, with black complexion and hair, and notes that James previously worked as a laborer. Initially, James enlisted as a private, but that changed a few months later when the US Army promoted him to corporal. Enlistment records do not provide an explanation behind this promotion, but it is likely that his prior service in the Navy contributed to the decision to promote him. James’ time in the service was both common and unique when compared to other USCI soldiers...A few months after his marriage to Annie, James sadly contracted smallpox and passed away at the Marine Hospital in Charleston, South Carolina on July 27, 1865. Civil War soldiers commonly fell victim to diseases due to as unsanitary conditions combined with a lack of medical knowledge or supplies made disease one of the leading causes of death for soldiers. Particularly for Black soldiers, supply and manpower shortages because of racial discrimination led to a higher mortality rate for those who contracted diseases. Another soldier from his company in the hospital at the same time remembered helping lower James into his coffin after he passed away. James’ death presents a stark reminder of two important insights that many USCI soldiers experienced broadly. First, even though Black regiments rarely had the opportunity to participate in combat, that did not mean that they did not face hazardous conditions or the prospect of death. Second, the fact that James passed away after the Confederate armies surrendered adds more grief to this situation. The US Army’s late decision to enlist Black soldiers produced the unintended consequence where Black soldiers’ three-year enlistment pushed their service beyond 1865. This meant that while many of their White comrades returned home, they continued to confront the hazardous conditions and diseases associated with military service." Elias Lottery"Like many of the African-American men who served in the US Army from Talbot Island and nearby, Elias’ life and wartime experience demonstrates the dangers USCI soldiers faced even while serving away from the front lines, as well as the ability of these men to reshape their lives during and after the Civil War. Elias Lottery was born on Talbot Island, Florida, around 1832. Sam Houston, part of the prominent Houston family in the area, enslaved Elias and his family.Born into slavery, Elias spent his early life and adolescence on the Houston plantation on Talbot Island. While historic documentation provides little details about his life under slavery, historians have documented certain experiences that enslaved individuals commonly went through. For example, living under the terrible conditions of slavery presented physical and psychological dangers to the individual and their families. As such, enslaved individuals like Elias sought to create kinship networks that either worked as an additional support system alongside a nuclear family, or in the relatively common occurrences that the slave trade separated families, these kinship networks functioned as a stand-in for the family.2 Once again historical documentation provides little details about Elias family; however, his pension file does demonstrate that Elias managed to create a strong network of friends among other enslaved individuals like George Floyd and Amos Atkinson.3 The relationships created while enslaved proved vital to these men for the rest of their lives through emancipation, service in the military, and after the war during the era of Reconstruction.Sometime before December 1862, Elias escaped slavery and made his way to Beaufort, South Carolina.4 While his pension file does not give specific details, given the location of Talbot Island at the mouth of the St. Johns River, Elias had several options available for emancipation. First, Elias might have escaped on a US Navy vessel while elements of the fleet were in the St. Johns River area and traveled to South Carolina on that ship. The second possibility is that Elias, like many other enslaved individuals, escaped to Fernandina, Florida, where there was a contraband camp. While at the contraband camp, it is possible that he took a naval vessel to South Carolina. Either way, Elias managed to escape slavery and arrive in Beaufort, S C. Now emancipated from slavery, Elias faced the similar complex task of many freedmen and women, that is what did their new freedom mean and what did it look like. While most assuredly a joyous occasion, arriving at contraband camps presented these formerly enslaved individuals with limited and tenuous circumstances in which they could work out the meaning of their newly found freedom. For Black men like Elias, the military provided a way for stable pay, raised social status, or the chance to defeat slavery. Elias, like many USCI recruits, decided to enlist due to a combination of many of these and other motivations. Therefore, in an expression of his newly found freedom Elias enlisted in the USCI on December 1, 1862. When he enlisted in the army, his enlistment information listed him as 5 ft 9 inches, black complexion, black eyes, dark hair, 30 years old, and listed him as a laborer. Elias enlisted 12 into the 1st South Carolina, which later became the 33rd USCI, in company H, under Captain Dolly. Through the first 6 months of his service, Elias’ muster rolls note his presence with his company. During that time, the 33rd participated in occupation duty in various Sea Islands around Charleston. Although USCI regiments like the 33rd that participated in occupation duty rarely saw battle with Confederates, USCI soldiers faced several other dangers. Most prominent among these other dangers was disease. A lack of medical knowledge, combined with unsanitary camps, made disease a truly lethal force that all soldiers faced.6 However, for newly freed Black soldiers like Elias, who spent much of their lives isolated on plantations and thereby lacked a strong immune system, disease had an outsized and tragic impact. During May and June of 1863 on account of sickness, Elias spent time at Fernandina, Florida. Fortunately, Elias managed to recover from his illness and on July 1863 returned to his regiment. Along with disease, occupation duty brought with it dangers due to the physical labor of carrying supplies, marching, or other manual labor. During the summer of 1863, while stationed in Camp Saxton at Beaufort, Elias suffered a “rupture,” or hernia. According to his lifelong friend, Amos Atkinson, Elias suffered a hernia that was caused “by severe drilling and discipline.” After his injury, Elias was examined by surgeon J. W. Hawks, a prominent abolitionist who along with his wife worked as surgeons for the USCI as well as teaching Black soldiers to read and write. By October 1863, the US Army decided to discharge Elias from the service on account of his injury. After his discharge, Elias returned to Fernandina, where he continued to live until his death in 1890. While no longer under the shackles of slavery, Elias still faced the complex task of realizing the liberty and freedom he obtained through his emancipation. As former Confederates regained political control of the South during reconstruction, Blacks saw their political, social, and economic freedom increasingly limited. Despite these limitations, Elias found economic stability as he worked in several jobs, including raftsman and farmer. However, the injury obtained during his Civil War service continued to plague him and made it a struggle to perform manual labor. In August 1879, Elias married Julia Walker at the Zion Baptist Church in Fernandina by the local pastor Reverend Louis Cook. Soon after their marriage, Julia gave birth to their first child, which they named Silas Floyd Lottery." Full citations and even more stories and context will be included in the full report. More Civil War History |

Last updated: March 26, 2024