Image courtesy of Florida Center for Instructional Technology, University of South Florida "…Anything Like an East Wind, This Bar is Impossible…"

Pilot Town began as a response to the dangerous conditions at the mouth of the St. Johns River. The barrier islands, numerous creeks and difficult channels around the entrance of the St. Johns were typical of many access points to Southern ports. However, the St Johns was not an ideal port when compared to others, such as Fernandina on the St. Mary's River, due to the especially challenging and shifting sand bars that formed over the river mouth that became even more dangerous with tide and weather. A newspaper account detailing the arrival of the Union fleet in early 1862 recorded that "it was so rough and the captain did not know the channel so he did not dare not try to run in… it is well he did not for the channel was so crooked that he could have never found it." Other wartime Union reports recount ships having to wait up to a week or more for the right conditions to safely cross the bar. Pilot Town had been established before the war as a residence for river pilots and their families, including free and enslaved blacks, which guided ocean-going ships into the river. Yet when the Union blockade fleet first arrived to the area, Pilot Town had been abandoned as the result of threatened Confederate reprisals for aiding the enemy. This was likely a part of an early Confederate effort to prevent Union control of the river that also involved the removal of the lenses from the lighthouse and the construction of Fort Steele across the river at Mayport.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress

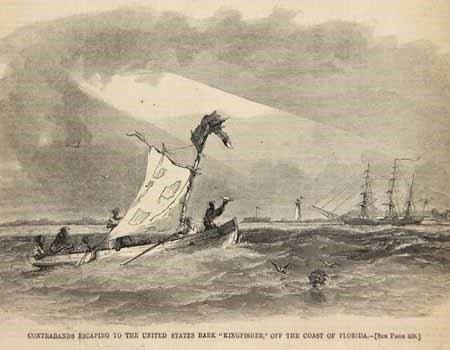

Image courtesy of the State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory Although President Lincoln had avoided talk of abolishing slavery early in the war, slaves increasing took flight from plantations in hopes of gaining their freedom as the Union took control of coastal areas. These contraband would make their way to the shoreline and hide in isolated swampy areas until sighting a patrolling Union ship, which they would then signal from shore or access by taking small watercraft out into the river. Though potentially dangerous, this still represented a much easier way to escape bondage than pre-war routes that required long overland distances to the North. At the start of the war the Lincoln Administration and the Department of the Navy were not prepared for the influx of contraband into Union controlled areas. This left Naval commanders unsure of procedure on how to deal with these peoples and lacking a coherent plan to address needs such as food, shelter, and medical care. Therefore, contraband policy and practice along the St. Johns was formulated in response to local conditions.

The First Confiscation Act in August of 1861 allowed for the seizure of slaves, although not technically freeing them, whose owners had employed them in the construction of Confederate defenses. However, it did not apply to slaves belonging to owners still loyal to the Union or slaves in areas under Union occupation. The Navy further complicated policy by encouraging its officers to retain fugitive slaves but did not prevent their return if the individual officer saw fit. Though there are numerous examples of contraband from the Jacksonville area being returned to their owners during the first half of 1862, the difficulty of disproving a fugitive slave's claim of conscripted labor often left Union Naval commanders to err on the side of protecting the contraband that approached them. Regardless of their moral view of slavery, the Navy along the St. Johns increasingly saw slavery as a cause of the war and thus slavery's end as a way to likewise end the conflict. A report from a Union vessel patrolling the river remarked, "the whole banks of the river as far as one can see is planted with corn…enough is in Florida for all the southern rebel states… if we carry their [slaves] off they cannot gather it." Further strengthening of this local contraband policy came from the actions of Confederate guerilla forces along the St. Johns who were under orders to hang any captured sailors as "kidnappers." By mid 1862, questions about contraband policy were cleared up when news of the Second Confiscation Act reached the St. Johns. This act no longer required the return of any fugitive slaves and granted freedom to those of disloyal Confederate owners, while the Emancipation Proclamation following a few months later, granted all North Florida slaves their freedom.

|

Last updated: July 17, 2020