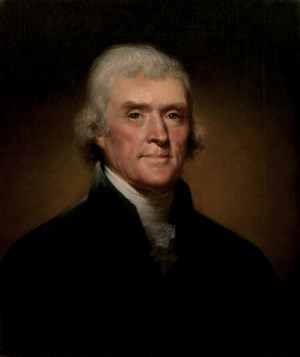

In 1752, when Jefferson was about nine years old, the family returned to Shadwell. His father died five years later and bequeathed him almost 3,000 acres; he became head of the family. In 1760, at the age of 17, he matriculated at the College of William and Mary, in Williamsburg. An incidental benefit of this education was the chance to observe the operation of practical politics in the colonial capital. He was graduated in 1762, studied law locally under the noted teacher George Wythe, and in 1767 was admitted to the bar. At Shadwell, Jefferson assumed the civic responsibilities and prominence his father had enjoyed. In 1770, when fire consumed the structure, he moved to his nearby estate, Monticello, where he had already begun building a home. Two years later, he married Martha Wayles Skelton, a widow. During their decade of life together, she was to bear six children, one son and five daughters, but only two of the latter reached maturity. Meanwhile, in 1769 at the age of 26, Jefferson had been elected to the House of Burgesses, in Williamsburg. He was a member continuously until 1775, and aligned himself with the anti-British group. Unlike his smooth-tongued confreres Patrick Henry and Richard Henry Lee, Jefferson concentrated his efforts in committee work rather than in debate. A literary stylist, he drafted many of the revolutionary documents adopted by the House of Burgesses. Jefferson utilized the same methods in the Continental Congress (1775-76), where his decisiveness in committee contrasted markedly with his silence on the floor. His colleagues, however, rejected several of his drafts the first year because of their extreme anti-British tone. But by the time he returned the following May after spending the winter in Virginia, the temper of Congress had changed drastically and by July, the Continental Congress voted to separate from Great Britain. Jefferson, though only 33 years old, was assigned to the five-man committee chosen to write a document explain to the world why the colonies had chosen such a drastic course of action. His associates assigned to the task to Jefferson, and today he is perhaps best known as the principal author of the Declaration of Independence. A notable career in the Virginia House of Delegates (1776-79), the lower house of the legislature, followed. Jefferson took over leadership of the "progressive" party from Patrick Henry, who relinquished it to become governor. Highlights of this service included revision of the state laws (1776-79), in which Jefferson collaborated with George Wythe and Edmund Pendleton, and authorship of a bill for the establishment of religious freedom in Virginia, introduced in 1779 but not passed until seven years later. Although not helped in his term as governor (1779-81) by wartime conditions and constitutional limitations, Jefferson proved to be a weak executive, even in emergencies hesitating to wield his authority. When the British invaded Virginia in 1781, he recommended combining the civil and military agencies under General Thomas Nelson, Jr., and virtually abdicated office. Although he was later formally vindicated, the action fostered a conservative takeover of the government and his reputation remained clouded for some time. Jefferson stayed out of the limelight for the next two years, during which time his wife died. In 1783 he reentered Congress, where he sponsored and drafted the Ordinance of 1784, forerunner of the Ordinance of 1787 (Northwest Ordinance). In 1784 he was sent to Paris to aid Benjamin Franklin and John Adams in their attempts to negotiate commercial treaties with European nations. During his five year stay, Jefferson succeeded Franklin as Minister to France (1785-89), gained various economic concessions from and strengthened relations with the French, visited England and Italy, absorbed European culture, and observed the beginnings of the French Revolution. Jefferson returned to the United States in 1789. In the years that followed interspersed with pleasant interludes and political exile at Monticello, he filled the highest offices in the land. Ever averse to political strife, he occupied these positions as much out of a sense of civic and party duty as personal ambition. Aggravating normal burdens and pressures were Jefferson's feuds with Alexander Hamilton on most aspects of national policy, as well as the vindictiveness of Federalist attacks. These clashes originated while Jefferson was Secretary of State (1790-93) in Washington's Cabinet. Unlike Hamilton, Jefferson sympathized with the French Revolution. He favored states’ rights and opposed a strong central government. He also envisioned an agricultural America, peopled by well-educated and politically astute yeomen farmers. Hamilton took the opposite position. These political and philosophical conflicts resulted in time in the forming of the Federalist Party and Democratic-Republican Party, which Jefferson cofounded with James Madison. In 1793, because of his disagreements with Hamilton and Washington's growing reliance on Hamilton for advice in foreign affairs, Jefferson resigned as Secretary of State. For the next three years, he remained in semi-retirement at Monticello. In 1796 Jefferson lost the presidential election to Federalist John Adams by only three electoral votes and, because the Constitution did not then provide separate tickets for the president and vice president, became vice president (1797-1801), though a member of the opposing party. In 1800 the same sort of deficiency, soon remedied by the 12th Amendment, again became apparent when Democratic-Republican electors, in trying to select both a president and vice president from their party, cast an equal number of votes for Jefferson and his running mate, Aaron Burr. Only after a tie-settling election in the Federalist-controlled House of Representatives (that rended both parties) did Jefferson capture the presidency; Burr became vice president. Jefferson, who was the first Chief Executive to be inaugurated at the Capitol, called his victory a "revolution." Indeed, it did bring a new tone and philosophy to the White House, where an aura of democratic informality was to prevail. And, despite the interparty acrimony of the time, the transition of power was smooth and peaceful, and Jefferson continued many Federalist policies. Because the crisis with France had terminated, he slashed army and navy funds. He also substantially reduced the government budget. Although he believed in an agrarian America, he encouraged commerce. From 1801-05 Jefferson deployed naval forces to the Mediterranean to subdue the Barbary pirates, who were harassing American vessels. During his term, to counter English and French interference with neutral American shipping during the Napoleonic Wars, he applied an embargo on foreign trade for the purpose of avoiding involvement. But this measure proved to be unworkable and unpopular. Jefferson's greatest achievements were in the realm of westward expansion, of which he was the architect. Foreseeing the continental destiny of the nation, he sent the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-06) to the Pacific, though he knew it had to cross territory claimed by foreign powers. While that project was being organized, Jefferson's diplomats at Paris consummated the Louisiana Purchase (1803), which doubled the size of the United States and extended its boundaries far beyond the Mississippi. In 1809 Jefferson retired for the final time to Monticello. He continued to pursue his varied interests and corresponded with and entertained statesmen, politicians, scientists, explorers, scholars, and Indian chiefs. When the pace of life grew too hectic, he found haven at Poplar Forest, his retreat near Lynchburg. His pet project during most of his last decade was founding the University of Virginia (1819), in Charlottesville, but he also took pride in the realization that two of his disciples, James Madison and James Monroe, had followed him into the White House. Painfully distressing to Jefferson, however, was the woeful state of his finances. His small salary in public office, the attendant neglect of his fortune and estate, general economic conditions, and debts he inherited from his wife had taken a heavy toll. When a friend defaulted on a note for a large sum, Jefferson fell hopelessly into debt and was forced to sell his library to the government. It became the nucleus of the Library of Congress. Jefferson died only a few hours before John Adams at the age of 83 on July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. Thomas Jefferson is buried at his beloved Montiecello, below an epitaph of his own composing: Here was buried

Thomas Jefferson Author of the Declaration of American Independence of the Statue of Virginia for religious freedom & Father of the University of Virginia |

Last updated: October 6, 2021