American naval victories in the War of 1812 are most commonly associated with the six super frigates such as the USS Constitution and USS United States that represented the highest level of naval technology available at the time. But American triumphs occurred with smaller ships as well.

Every time an American naval vessel returned to port with some claim to fame, churches rang their bells, guns fired salutes, and the people in the street celebrated their heroes with a parade.

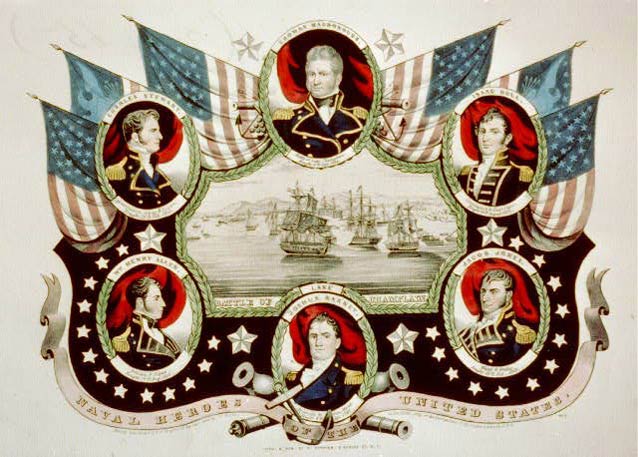

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

On October 18, 1812, the 18-gun sloop Wasp had the effrontery to attack a British convoy and then captured the 22-gun Frolic. Unfortunately for the Americans, no sooner had the Wasp beaten the larger British vessel than a 74-gun British ship appeared, forcing the hobbled Wasp—its rigging was in shambles from the battle—to surrender. The Americans scored another victory on February 24, 1813, when the brig Hornet met the Peacock off the coast of South America. The battle was short and brutal. Although the vessels were about the same size, the Hornet had more firepower, was better handled, and had more effective gunnery. In a matter of minutes, the Hornet so overwhelmed the Peacock that it soon sank. (The Hornet would also beat another vessel of equal size, the Penguin, in the South Atlantic on March 23, 1815.)

There were also some defeats. The British gained an important symbolic victory when the Shannon defeated the Chesapeake on June 1, 1813, in a battle off Boston in which Captain James Lawrence uttered the famous words “Don’t give up the ship” shortly before the Americans had to haul down their colors after the loss of over the a third of the crew.

Many of these battles assumed the aura of a duel between two knights-errant as officers in the American and British navies believed in a code of honor in combat that prized manliness and duty. Captain Lawrence, for example, could have avoided his loss, and the bloodshed that accompanied it, had he remained focused more on what damage they might do to enemy commerce than glory in a ship-to-ship engagement. Likewise, British captains early in the war did not shy away from fighting the American super frigates, like the United States and the Constitution.

The public in both nations eagerly sought word of these confrontations and romanticized the exploits of their hero officers, regardless of the gruesome reality of battles at sea. They also trumpeted the common seamen who manned these ships as defenders of the nation. If each side lionized the captains and their crews, they demonized the enemy. When word arrived in London of the capture of Captain Porter, whom the British newspapers had proclaimed a buccaneer, Parliament cheered. Every time an American naval vessel returned to port with some claim to fame, churches rang their bells, guns fired salutes, and the people in the street celebrated their heroes with a parade.

Part of a series of articles titled “The Luxuriant Shoots of Our Tree of Liberty:” American Maritime Experience in the War of 1812 .

Last updated: March 6, 2015