While some plants decorate the landscape and are very visible at Rocky Mountain National Park, others are seldom seen. Tiny floating plants, called algae, live in lakes, wetlands, and ponds. Individual algae are virtually invisible, but when they congregate, they turn into the green 'slime' on stream rocks. Algae are important because they produce oxygen, provide food for themselves (photosynthesis) as well as food for larger aquatic (water living) animals. Found in the world's streams, lakes and oceans, algae produce more oxygen than all the rainforests of the world combined. AlgaeAlgae are divided into four sub-groups based on the type of pigment they use to photosynthesize.

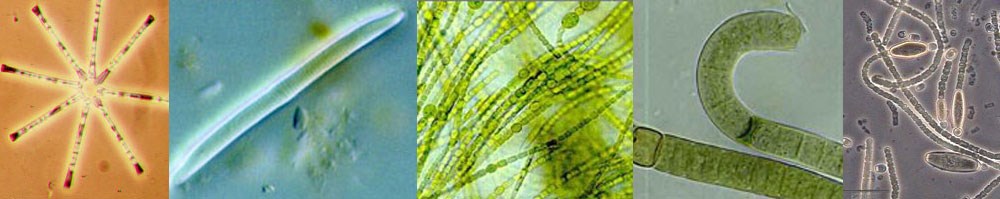

DiatomsDiatoms are single-celled, eukaryotic microbes that form the base of the food chain in many aquatic ecosystems. They are a diverse group of algae (there are over 60,000 species described world-wide). They can live in harsh environments; diatoms have been reported growing under more than 14 feet of ice in Antarctica. They occur over nearly 8 orders of magnitude of pH, surviving in acid mine drainages and others thrive at about pH of 10 (where silica begins to dissolve!). Diatom cell walls are made out of silica (just like window glass) and they can remain in the layers of sediments at the bottom of lakes for thousands of years. These sediment layers can be read somewhat like tree rings and tell us what the ecosystem was like in the distant past. Fossil diatoms even offer a unique window into current analyses of climate change. Scientists studying algae in Rocky Mountain National Park have documented 78 different species in one study. Initial observations of a recent study suggest the park has little-known or rare species, and over 40 newly described species. Scientists are especially interested in diatoms because they are biomonitors, indicators of ecosystem conditions. Diatoms convert carbons to sugars, take up CO2 and release O2. Diatoms divide one to several times a day, meaning that a single cell can turn into a billion cells in the course of a month. Thus, they react almost instantaneously to the environmental conditions they face. By studying the kinds of diatoms present, scientists can determine if acid rain is falling, if heavy metals are in the water, if the lake is productive, and other things about the health of the park's aquatic ecosystems. The diversity of diatom species and the large number of individuals (often numbering millions per square centimeter) lend statistical robustness to these environmental studies of aquatic habitats. As interesting and useful as diatoms are to scientists, they are also very beautiful. When visiting ice covered lakes, ponds, and wetlands in Rocky Mountain National Park in winter or watching the sunlight glint off the water in the summer, it is intriguing to wonder what interesting plants may be lurking just below the surface. To lean more on the recorded algae and diatoms of Rocky Mountain National Park view the Algae List and Diatom List. Photos

|

Last updated: May 5, 2018