Library of Congress 1829- Isaac Peirce and the building of the mill

Running the millIsaac was not a miller and didn't run the mill himself. He leased the mill to others who operated it for him. Milling was a lucrative business in the Washington area during the 1800s so the building of the mill in 1829 was a good investment at the time. It is believed that the previous mill, built by William Deakins in the 1790s, had used an Evans system and that Peirce transferred it into his new mill when it was built.

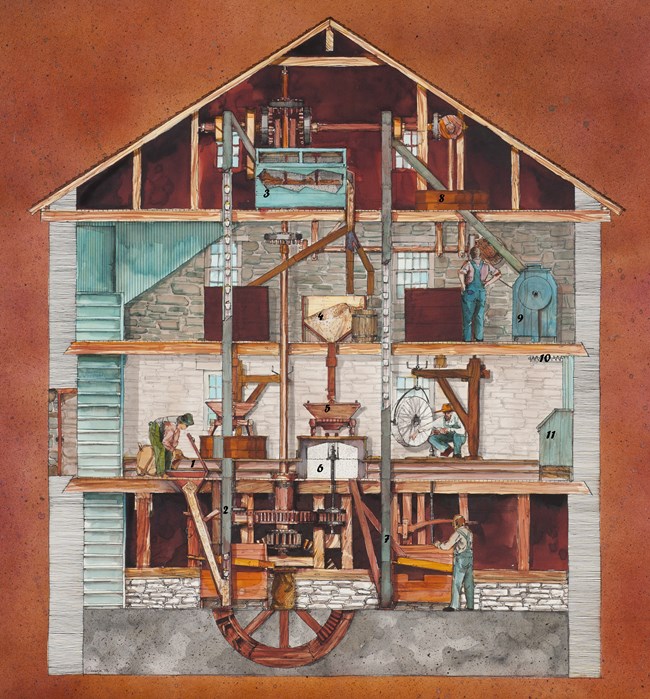

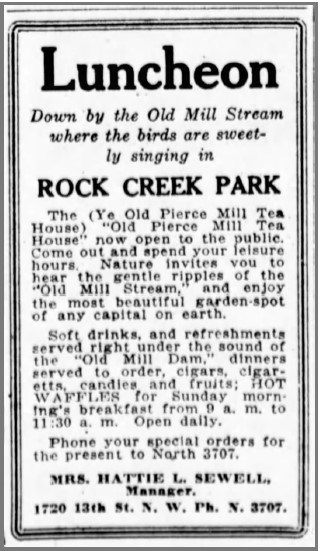

NPS How did it work?Water turned the wheel on the exterior of the mill which connected to a series of gears inside the mill's basement. These gears drove a shaft, like the axle on a car, that powered the machinery in the mill. 1870s & 1880s- By the numbersHow successful was the mill?Peirce Mill operated as a merchant and custom mill. It had three sets of mill stones and ground corn, wheat and rye. Two or three men could keep the mill working and grind an estimated 150 bushels of grain per day. Though earlier records have not been discovered, records from 1870 indicate that Peirce Mill produced 40 bushels of wheat flour, 150 barrels of rye flour, and ground 4,075 bushels of corn for animal feed for market. The same census records indicate that the mill custom ground 3,000 bushels of corn and rye flour, 632 bushels of animal feed, and 3,375 bushels of meal and flour. This was produced over the course of eleven months by two men who earned $500 in wages and had a production value of just over $5,000 (Historic Resource Study, pg. 38)The next census in 1880 indicated that Peirce Mill was being operated by three men; Charles and Alcibiades White, who paid $600 to operate the mill and a laborer they employed for one dollar a day. They ran the mill year round and was half-custom, half-merchant grinding. The value placed on the grinding was $8,250. They primarily ground corn meal (480,000 pounds of it) and animal feed (127,900 pounds) (HRS, pg 39). 1890s- Park beginnings, mill endingsThe federal government began buying land to create Rock Creek Park in the 1890s. The mill, carriage barn and springhouse were purchased from the descendents of Peirce Shoemaker, who had died in 1891. When the government purchased the mill, they made an agreement to allow the Whites, Charles and Alcibiades to keep their lease of the mill and continue to operate it.The Whites continued to lease the mill from the federal government until 1897 when the main shaft broke. The government assessed the damage and determined that it would cost more to repair the mill and keep it operating than was being generated from the lease. The decision was made to keep the mill closed. 1905 through 1934- Pierce Mill Tea HouseThe Mill was located along Peirce Mill Road just below where the Peirce Mill Bridge crossed the creek. The road (which would eventually be renamed Tilden Street NW and Park Road NW) had become a main east-west route across northwest Washington City. The location made the structure a candidate to be turned into a tea house and refreshment stand in the new park.In 1905 an enclosed porch was added where the water wheel had once turned and the Tea House opened it's doors with a succession of managers. Mary Louise Noble(1905-1915) The first manager of the teahouse. Florence I. Blake(1915-1919) Part of the Dolly Madison Candy Company, her contract was terminated when she failed to pay the $60-per-month rent on time and was reported for providing poor service. Hattie L. Sewell(1920-1921) A woman of color who obtained the concession for $45-month. Though her business was successful, park neighbors and Peirce-Shoemaker estate trustees complained to park management and her contract was not renewed. Girl Scouts Association of the District of Columbia(1921) Among the specialties offered were "Harding waffles," honoring the incumbent president. The Girl Scouts Association was allowed to use the second floor of the mill as living rooms for the attendant in charge. They did not keep the concession for very long. Welfare and Recreational Association of Public Buildings and Grounds, Inc.Took over from the Girl Scouts. They ran the tea house concession until 1934.

Washington Times Peirce or Pierce?The spelling of the last name Peirce was not standardized. The earliest census records show the name spelled "Peirce". Other census records show it spelled "Pierce." Still other records show the name spelled Pearce. Most records use the "Peirce" spelling though and that is what the National Park Service has decided to use most recently.

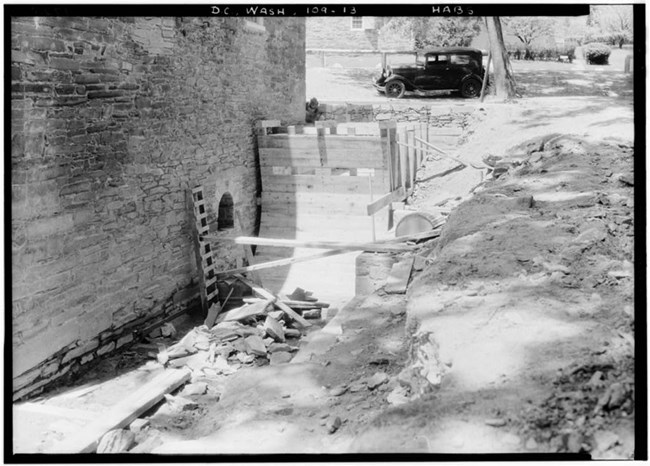

Library of Congress 1930s- Restoration at Peirce MillIn 1934, the new superintendent of National Capital Parks, C. Marshall Finnan proposed several restoration projects within Rock Creek Park. These projects would be funded through a public works project. The mill proposal for the mill project was approved by Department of the Interior secretary Ickes at a projected cost of $19,250.The enclosed porch was removed and a new water wheel was put on the exterior of the building. The inner workings of the mill, replicating the old Oliver Evans system that had run during the 19th century was also re-installed. When the project was completed in 1936, the total cost of restoring the mill to it's pre-Teahouse appearance was $26,614. Robert A. Little, a veteran miller, was hired to run the mill, which began operating on October 27, 1936. Meal ground at the mill was taken to cafeterias run by the Welfare and Recreational Association of Public Buildings and Grounds. It was also sold on site to members of the public where prices were advertised as "higher than in the stores."

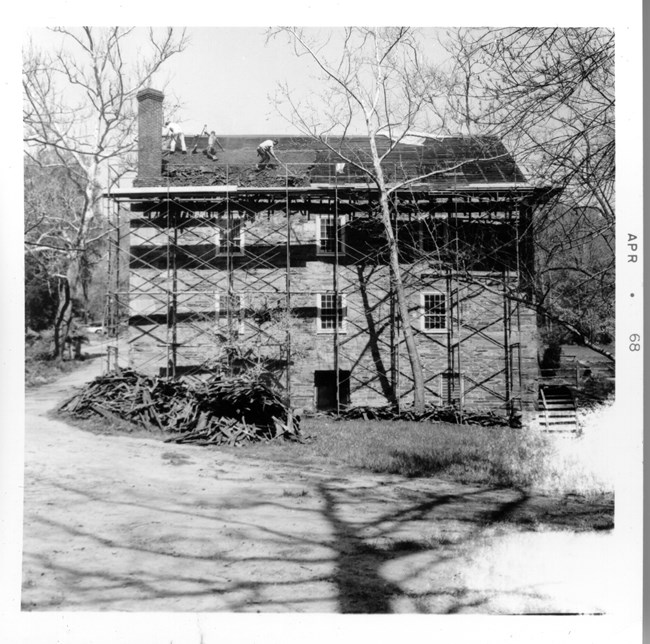

NPS Photo Peirce Mill in the 20th CenturyThe mill was operated through World War II and continued to provide meal to government kitchens, but it was never a huge money-maker. It ran sporadically until 1958 when operations came to a full stop. Problems with machinery, an inability to find trained millwrights, fluctuating water levels in Rock Creek were all contributors to the stop in operations.In 1967, there was interest in re-starting the mill. Research showed that the undershot wheel that had been installed during the 1935 restoration was an inaccurate representation. A new over-shot wheel was installed to be more in-sync with historic authenticity. Another improvement to the mill was the use of municipal water used to move the wheel. Skilled millwrights were located and in 1970 the mill once again ground corn under the watchful eyes of Robert Batte and then Brian Gregorie. Tropical storms in the 1970s damaged the equipment yet again and the mill ran sporadically until 1993 when the mill experienced a catastrophic failure with the main shaft. New friends and new life in the 21st CenturyPeirce Mill re-opened as an operating mill in 2011 with the help of a not-for-profit group called "The Friends of Peirce Mill." This organization helped raise funds, secure grants and assisted the National Park Service with getting the mill restored to the point that it could once again grind corn. The mill now provides an opportunity for visitors to see and hear what life in the mill was like during the 1800s and the mill's hey-day and school groups learn about engineering and local history on field trips to the site. Projects to continue the restoration of the mill are ongoing.

For information on when the mill is open to visit, please go to our Operating Hours &Seasons Page. Additional information on the mill can also be found on our Places page |

Last updated: March 5, 2021