In 2022, photographer Ted Barone worked with Redwood National Park staff to create a series of photo montages that show some of the historic sites along the whole redwood coast. It is fascinating to see how these places have changed over time.

Indigenous People Prior to Euro-American contact, Native Americans had adapted well to this bountiful environment. Their profound religious beliefs, extensive knowledge of the natural world, languages, customs, and perseverance continue to be a source of admiration for other cultures. Native Americans in the region belonged to many tribes, although no one tribe dominated. Indeed, the concept of "tribe" does not describe very well the traditional political complexity of the area. There were scores of villages that dotted the coast and lined the major rivers; each of these villages was more or less politically independent, yet linked to one another by intricate networks of economic, social, and religious ties. Food sources important to the native peoples included deer, elk, fish from the ocean, rivers, and streams, nuts, berries, and seeds. Efficient and reliable hunting, fishing, and gathering methods were always paired with a deep spiritual awareness of nature's balance.

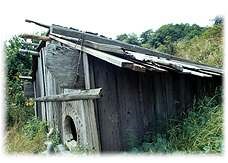

Traditional homes of the region's American Indians usually were constructed of planks split from fallen redwoods. These houses were built over pits dug beneath the building, with the space between the pit and the walls forming a natural bench. A house was understood to be a living being. The redwood that formed its planks was itself the body of one of the Spirit Beings. Spirit Beings were believed to be a divine race who existed before humans in the redwood region and who taught people the proper way to live here. Anglo settlers and immigrants pushed the indigenous people off their land, hunted them down, scorned, raped, and enslaved them. Resistance – and many of the Native Americans did resist – was often met with massacres. Militia units composed of unemployed miners and homesteaders set forth to rid the countryside of "hostile Indians", attacking villages and, in many documented cases, slaughtering men, women, and even infants. Upon their return, these killers were treated as heroes, and paid by the state government for their work. Treaties that normally allotted Native Americans' reservations were never ratified in this part of California. Although treaties were signed, the California delegation lobbied against them on the grounds that they left too much land in Indian hands. Reservations were thus never established by treaty, but rather by administrative decree. To this day, the displacement of many tribes, the lack of treaty guarantees, and the absence of federal recognition of their sovereignty continue to cloud the legal rights of many American Indians. *Text based on Living in a Well-Ordered World.

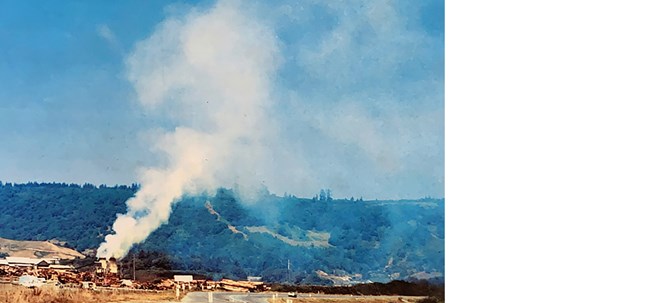

Indigenous People Today Despite dreadful events of the past 150 years, the indigenous community of northwestern California has persisted. It has, in fact, done more than persist. Whether in politics, art, religion, or any other area of life, the community exhibits great variety and vigor. There is currently no one in the area who is living the way Native Americans did prior to 1850, any more than there is a member of an Anglo culture who is living the life of a mid-nineteenth century miner, farmer, or merchant. While some Native Americans in the country do live on reservations, near or on the land of their ancestors, others live in local towns and cities. Culture is not a "museum" set in time and statically preserved. Living cultures grow, change, and adapt, and this has certainly been the case with Native American culture. The people of northwestern California form a vital, changing community, whether Yurok, Hupa, Tolowa, or Karuk. Yurok and Tolowa ancestral territories include land and resources now contained within Redwood National and State Parks. Tribal Councils and Park management work together on myriad of government to government programs like habitat restoration, the returning of California condors, protection of archeological sites, the use of prescribed fire, and the beneficial sharing of staff and agency resources. Logging When gold was discovered in northwestern California in 1850, the rush was on. Thousands of immigrants crowded the remote redwood region in search of riches and new lives. These people were no less dependent upon lumber, and the redwoods conveniently provided the wood the people needed. The size of the huge trees made them prized timber, as redwood became known for its durability and workability. At first, axes, saws, and other early methods of bringing the trees down were used. It could take weeks for a hand crew to fell, cut, and transport one redwood tree. By 1853, nine sawmills were at work in Eureka and large stands of redwoods began to disappear by the close of the 19th century. Land fraud was common, as acres of prime redwood forests were transferred from the public domain to private industry. Although some of the perpetrators were caught, many thousands of acres of land were lost in land swindles. By the 1910s, some concerned citizens began to clamor for the preservation of the dwindling stands of redwoods. The Save-the-Redwoods League was born out of this earnest group, and eventually the League succeeded in helping to establish the redwood preserves of Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park, Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park, and Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park. Save the Redwoods League By the late 1910s, it became obvious that many stands of old-growth redwoods were about to be logged. Because the trees had been linked with fossil records millions of years old, they were looked upon as a living link with the past. Thus, the urge to protect these stands came not from an aesthetic concern, but rather a scientific one. Paleontologists Henry Fairfield Osborn of the American Museum of Natural History, Madison Grant of the New York Zoological Society, and John C. Merriam of the University of California at Berkeley founded Save the Redwoods League in 1918. The League was formed as a nonprofit organization dedicated to buying redwood tracts for preservation. Through donations and matching state funds, the League bought over 100,000 acres of redwood forest between 1920 and 1960. The majority of these purchases consisted of North Coast redwood groves. The California Department of Parks and Recreation created Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park, Del Norte Coast Redwoods State Park, Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park, and Humboldt Redwoods State Park in the early 1920s with these lands. The Memorial Grove Program of Save the Redwoods League was started in 1921 when the first large donation was given to the League to purchase and dedicate a redwood grove. Now more than 700 memorial and honor groves, named for individuals and organizations, have been established in California State Parks and Redwood National Park, with more being added each year.

NPS and CDPR When redwood harvesting began in the early 1850s, over two million acres of old-growth redwood forests existed. But Euro-Americans took less than 60 years to reduce this number into hundreds-of-thousands of acres. By the late 1910s, a preservationist group called the Save-the-Redwoods League began purchasing large tracts of redwood acreage in an effort to save the quickly disappearing forests. The State of California pledged to match funds put forth by the League, and between 1920 and 1960, over 100,000 acres were set aside through this partnership. In the early 1920s, the state of California established the three state parks, as well as Humboldt Redwoods State Park to the south, with the purchased lands. Since these early days, the state park system has protected the parks’ natural and cultural resources while welcoming visitors to explore the redwood groves and surrounding ecosystems. However, logging continued outside the state parks, and as the years passed by, conventional thinking about the environment changed as well. In the 1960s, more emphasis was placed upon the importance of preserving whole ecosystems as opposed to just portions of ecosystems. Aided by the Sierra Club and the National Geographic Society, the Save-the-Redwoods League now called for Congress to create a national park that would include land in the Redwood Creek area adjacent to the state parks. By this time, 90 percent of the original redwoods had been logged. After much controversy and compromise with timber companies, Congress finally approved a federal park, and on October 2, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the act that established Redwood National Park. The new preserve placed 58,000 acres in the care of the NPS. Some of Redwood National Park included state park lands, which were still under state jurisdiction. Also, NPS land included the Tall Trees Grove along Redwood Creek, which remained at risk from upstream logging. As the logging continued into the 1970s, sediment loads increased dramatically along Redwood Creek, threatening the health of the streamside redwoods. In 1977, Representative Phillip Burton introduced legislation to expand the federal park. Despite much opposition from the timber industry, in March 1978, President Jimmy Carter signed into law the addition of 48,000 acres to Redwood National Park. This addition widened the protection in Redwood Creek, although 39,000 acres of the addition were already logged over. Restoration of these lands commenced and continues today. And then, in 1994, the NPS and CDPR agreed to jointly manage the four parks for the best resource protection possible. RNSP today form a World Heritage Site and are part of the California Coast Range Biosphere Reserve, designations that reflect worldwide recognition of the parks’ natural resources as irreplaceable.

|

Last updated: November 23, 2022