coastal dune restoration project includes: Coastal Dune Restoration Project The National Park Service (we) want to restore 600 acres of coastal sand dunes. These dunes are critical to the survival of endangered and threatened plants and animals. We plan to remove non-native iceplant and beachgrass with a combination of mechanical removal, manual removal, and spot spraying of herbicides. After 15 years of experience and intensive study, we decided to use herbicides as a last resort. We hope this FAQ (frequently asked questions) will answer some of your questions in plain language. For detailed, authoritative information, check our Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) (530 KB PDF) and the Environmental Assessment (13,741 KB PDF).

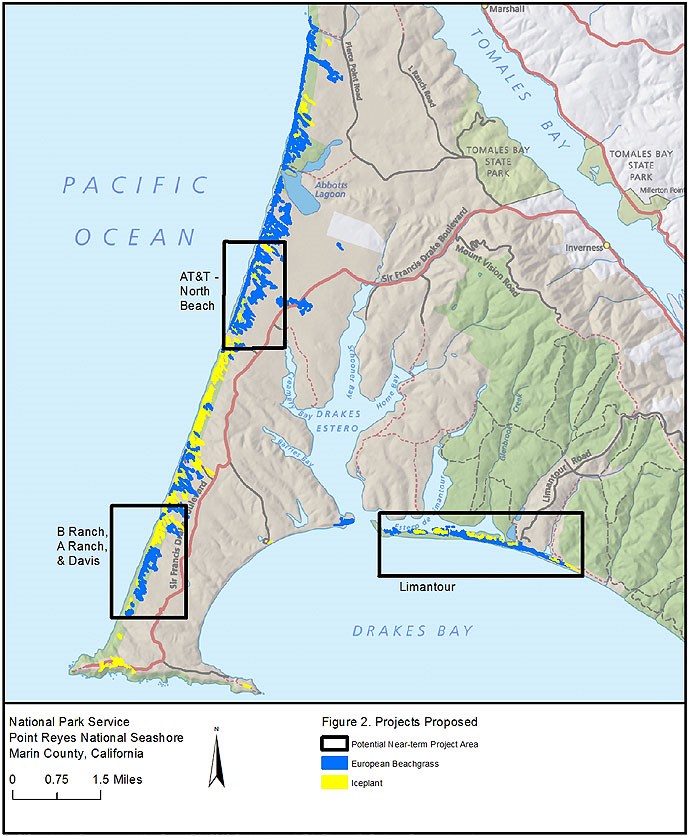

Why are you restoring coastal sand dunes? We want to restore coastal sand dunes by removing hundreds of acres of non-native plants. This should bring back habitat for birds, butterflies, and flowers threatened with extinction. Many decades ago, iceplant and European beachgrass began invading and stabilizing coastal sand dunes. By 2009, these plants carpeted more than 1,400 acres of the seashore. Populations plummeted for western snowy plovers, Tidestrom's lupine, and other threatened or endangered species living in the dunes. After we cleared 80 acres of dunes near Abbotts Lagoon, more than 15,000 Tidestrom's lupine plants sprouted. Snowy plovers moved in to nest and raise young. And the dunes started moving more naturally. For more information, visit our Why is Dune Restoration Important? How are you restoring coastal sand dunes? Mechanical removal means digging up plants with excavators and burying plants with bulldozers. Manual removal means pulling or digging up plants by hand. We plan to spot spray herbicides with a backpack sprayer and calibrated nozzle on dry, calm days. We might also use mowing and controlled burns for pre-treatment. Where are you restoring coastal sand dunes?

When will the project start? How do you know this project will work? How will you protect the environment?

Which endangered or threatened plants and animals will this project help?

NPS / Matt Lau Western snowy plover

© Geoff Smick. Myrtle's silverspot butterfly

Tidestrom's lupine

Beach layia Restoring coastal sand dunes should help many other native plants and animals thrive. What's the difference between natural dunes and stabilized dunes? Dunes stabilized by invasive plants look very different. The dunes closest to the ocean are steep, continuous ridges without blowouts. Farther from the ocean, dunes starved of new sand are slowly overgrown by bushes. One of the biggest differences is sand movement. Two years after we restored dunes near Abbotts Lagoon, sand had buried 10 acres of grassland, scrub, and wetland. Natural dunes also clean up groundwater better than stabilized dunes. How will climate change affect coastal sand dunes? Natural dunes can move in response to a changing climate. As they migrate, they will continue protecting the coast while providing homes for rare plants and animals. Dunes stabilized by invasive plants may erode into the ocean and gradually shrink. Eventually, storm surges and giant waves will wash over them, flooding inland areas, and destroying endangered species habitats. Restoring coastal sand dunes should make Point Reyes National Seashore more resilient to climate change and sea level rise. What are the most common concerns about this project? Why don't you use…? We tried burrowing deeper with an excavator, but digging up large areas can harm nearby ranches, dunes, wetlands, and threatened and endangered species. Some of the other techniques we've tried or studied include:

For this project, we plan to use a combination of mechanical removal, manual removal, and spot spraying herbicides. The National Park Service uses herbicides as a last resort, when we can't effectively control invasive plants using other methods. What is glyphosate? Will you use Roundup®? Roundup Custom does not contain a surfactant. We plan to add a different surfactant (Competitor®), which contains ingredients commonly found in food. The EPA has approved Competitor for use near wetlands. Why are you using glyphosate? Does glyphosate interfere with hormones? Environmental Protection Agency Memorandum. EDSP Weight of Evidence Conclusions on the Tier 1 Screening Assays for the List 1 Chemicals, June 29, 2015. Available at https://www.regulations.gov/contentStreamer?documentId=EPA-HQ-OPP-2009-0361-0047&disposition=attachment&contentType=pdf (accessed 30 March 2020). (1,043 KB PDF) Does glyphosate cause cancer? "…glyphosate does not pose a cancer risk to humans." We rely on EPA guidance for the proper use of all herbicides and pesticides. The EPA plans to complete a comprehensive review of glyphosate soon. If they revise glyphosate's risk assessment, we will reconsider our herbicide choice. The European Union and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization also concluded that glyphosate does not cause cancer. Environmental Protection Agency. Final rule. "Glyphosate; Pesticide Tolerances," Federal Register 78, no. 84 (May 1, 2013): 25396. Available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2013-05-01/pdf/2013-10316.pdf (accessed 08 October 2015). (240 KB PDF) Why did I read recently that glyphosate does cause cancer? However, in June 2015 the IARC also said:

The EPA and other agencies use the IARC information to conduct further research and determine the balance of risks and benefits of herbicides like glyphosate. We rely on EPA guidance for the proper use of all herbicides and pesticides. International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2015. IARC Monographs Volume 112: Evaluation of Five Organophosphate Insecticides And Herbicides. http://www.iarc.fr/en/media-centre/iarcnews/pdf/MonographVolume112.pdf (accessed 08 October 2015). (47 KB PDF) International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2015. IARC Monographs Questions and Answers. http://www.iarc.fr/en/media-centre/iarcnews/pdf/Monographs-Q&A.pdf (accessed 08 October 2015). (133 KB PDF) Does glyphosate kill butterflies, bees, birds, and other animals? The regular formula of Roundup® includes a surfactant that can harm aquatic life. We are using a different formula, EPA-approved for use near wetlands, which does not include that surfactant. Why don't you wait for the full EPA review of glyphosate? For this project, we plan to spot spray herbicides containing glyphosate starting in the fall of 2016. If the EPA completes their glyphosate review before we start, we plan to reconsider our herbicide choice. If the EPA changes the herbicide label directions, we will follow the new label. Will glyphosate from this project hurt nearby organic ranches? What is National Park Service guidance on glyphosate?

Will clearing the dunes dump sand into nearby ranches?

coastal dune restoration project includes: Coastal Dune Restoration Project |

Last updated: September 5, 2022