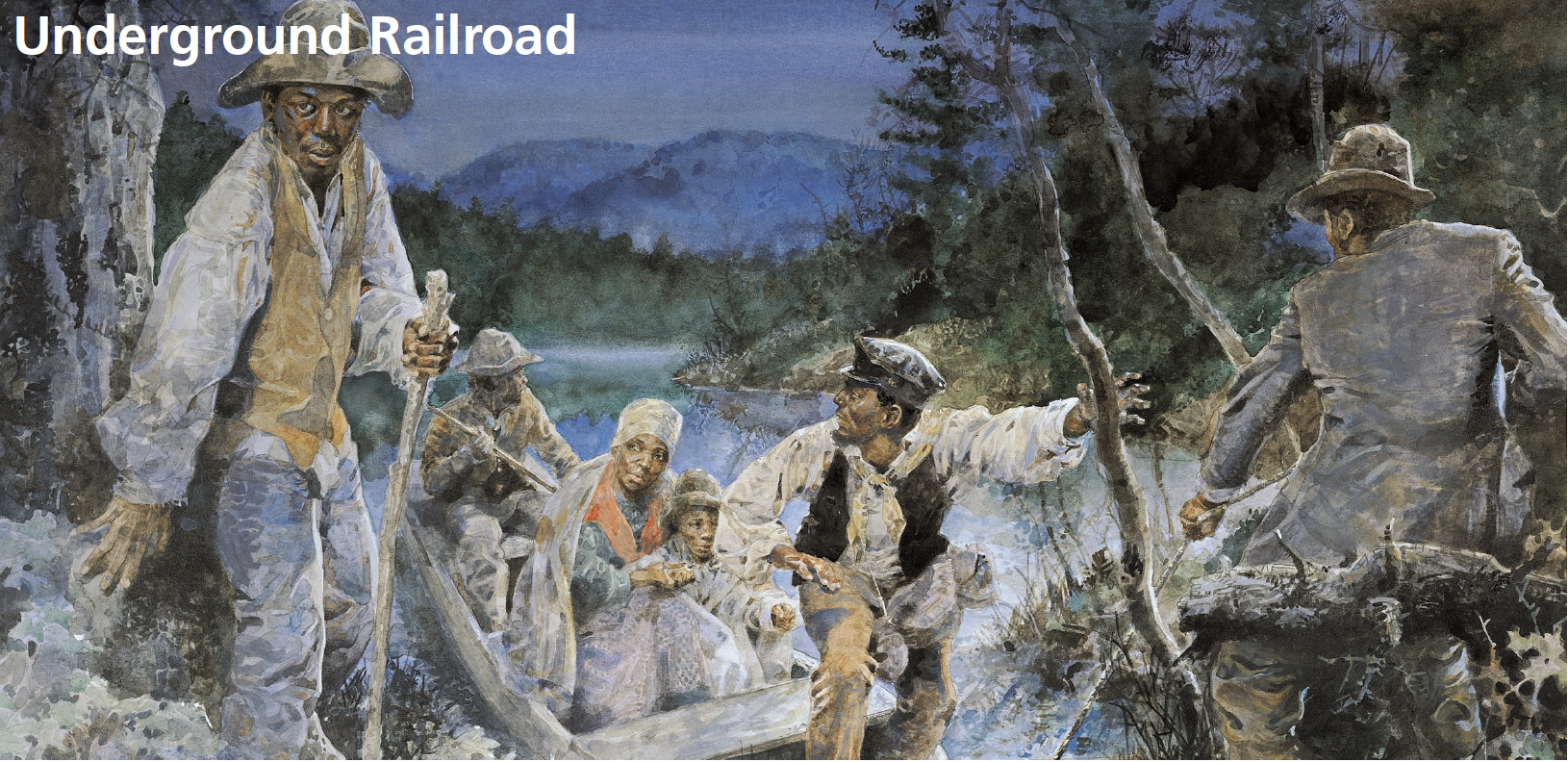

Copyright Jerry Pickney. 'At Alexandria, I crossed the Potomac River and came to Washington, where I made friends with a colored family, with whom I rested eight days. I then took the Montgomery road (sic), but,wishing to escape (illegible) and it being cloudy, I lost my course, and fell back again along the Potomac River, and traveled on the towpath of the canal from Friday night until Sunday morning…. (After an unsettling encounter with a man on horseback) I soon entered a colored person’s house on the side of the canal, where they gave me breakfast and treated me very kindly. I traveled on through Williamsport and Hagerstown, in Maryland, and, on the nineteenth day of July, about two hours before day, I crossed the line into Pennsylvania with a heart full of gratitude to God, believing that I was indeed a free man, and that now, under the protection of law, there was ‘none who could molest me or make me afraid.’

- James Curry from Person County, NC The Underground RailroadThe Underground Railroad was neither “underground” nor a “railroad,” but a loose network of people and places aidingenslaved Africans to freedom. Some 100,000 enslaved persons escaped the brutal chains of slavery in the years between the American Revolution and the Civil War. The Underground Railroad has been described as America’s first civil rights movement—the first social justice movement in this country to rally the races together. The Railroad and the RiverThe corridor designated by Congress for the Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail is commonly associated with the travels of George Washington, with the conservation of rivers and special places, and with the Civil War. The corridor’s lesser-known themes—the Underground Railroad among these—are equally significant. The Trail corridor includes areas within the District of Columbia, Maryland, Virginia and Pennsylvania that were once known as "free" and “slave” states at a time when the United States was embroiled in the institution of chattel slavery. Maryland and Virginia—important “slave states”—gave birth to the District of Columbia as the site of our Nation’s capital in 1800, while Pennsylvania was a “free state” and greatly sought by the enslaved. With many features of the Potomac riverscape hidden from view, the many creeks, points, and lookouts presented an opportunity for freedom to the enslaved. While researchers believe that the Trail corridor is rich in such historical information, attention to the use of the waterways as a means of escaping the oppression of slavery has received only minor attention. Research has shown, however, that the enslaved used absolutely any and all measures to free themselves, and the Potomac River was a part of such efforts: The Potomac is both deep enough for boats to ross and shallow enough, in places, for crossing on horseback or by wagon.Escape on the PearlThe most popular and well-documented escape attempt from the Nation’s capital occurred on April 15, 1848, when 77 enslaved persons fled their quarters in Washington City, Georgetown, and Alexandria. Waiting to aid them to freedom was a 54-ton bay-craft schooner called The Pearl. Docked at a secluded spot along the southwest wharf, the plan was to sail The Pearl and it’s freedom seekers southward on the Potomac River to the Chesapeake Bay, then up the bay to the Chesapeake & Delaware Canal and on to Philadelphia. This, the largest single escape attempt in United States history, was thwarted by a number of uncontrollable circumstances.First, the schooner was spotted and noted as suspicious by a captain of a steamer headed to Washington’s port, who reported the schooner’s movement. Second, as soon as the schooner reached the mouth of the Potomac a severe storm prevented access to the Chesapeake Bay. And then after having traveled more than 100 miles The Pearl was forced to seek refuge from the storm and dropped anchor in a small cove called Cornfield Harbor.

Historic Sites along the PotomacThe Pearl is just one example of the use of the Potomac River as an Underground Railroad route to freedom. During the 1830s and continuing late into the next decade, Washington, D.C. operated one of the most aggressive networks because of its location and its artful leadership (C. Peter Ripley, p. 58). John Brown’s raid, beginning at the Kennedy Farmhouse and ending at Harpers Ferry, symbolizes a turning point in the enslaved African’s struggle for freedom. In addition to the escape route ofThe Pearl, places in the Trail corridor associated with the Underground Railroad include the following:

An asterisk denotes site recognition by the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom. Additional ResourcesNational Underground Railroad Network to Freedom ProgramAlexandria Archeology Museum A hike along the Underground Railroad in Montgomery County: Underground Railroad Experience in Maryland Southern Maryland Studies Center Thomas Balch Library |

Last updated: April 24, 2018