Last updated: March 20, 2018

Person

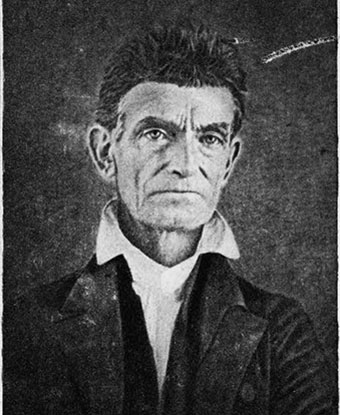

John Brown

Library of Congress

John Brown was born May 9, 1800 in Torrington, Connecticut. Soon after Brown’s birth, the family moved to Hudson, Ohio. As a youth he saw an enslaved boy, with whom he had become friends, badly beaten and harshly treated. This and his religious belief that slavery was a sin against God influenced his thoughts and actions throughout his life.

In 1816 he traveled east to study for the ministry but an inflammation of the eyes and a lack of funds forced him to give up this calling. He returned to Ohio and took up his father’s trade of tanning leather. In 1820 he married Dianthe Lusk. She gave birth to seven children, five of whom lived to maturity. In 1826 he moved his family to Richmond, Pennsylvania, built a tannery (with a secret room to hide escaping slaves), organized a church, and served as postmaster to the community. Dianthe died in 1832 and the following year he married Mary Ann Day. She bore thirteen children but only six lived to maturity.

In the ensuing years between 1835 and 1846, Brown pursued various occupations; farmer, tanner, surveyor and real estate speculator. In 1846, he formed a partnership in a wool business known as Perkins and Brown. The firm opened a warehouse in Springfield, Massachusetts, and Brown soon moved his family there.

At this time, he heard of the abolitionist Gerrit Smith of Peterboro, New York. Smith had opened up thousands of acres of land in New York State for the express purpose of giving the land to African American farmers. Much of this land was in the untamed Adirondack wilderness. In spite of many hardships, families came to this colony Brown called “Timbukto.” Brown wanted to join this venture and bought 244 acres at $1.00 per acre. In 1849 Brown moved his family there, to North Elba, New York. He surveyed his neighbors’ land, showed them how to clear their land, build cabins, and become self-sufficient.

Brown also continued to cultivate his interest in the wool business. He sailed for London to establish an English market for Perkins and Brown. His plan failed, forcing him to return to Ohio in 1851 and work off his debts to his partner. He eventually returned to North Elba, but his unceasing interest in the anti-slavery movement soon compelled him to go to Kansas.

Several members of his family were settling in the territory and they were in desperate need of assistance. The Kansas-Nebraska Act had created a battleground over the spread of slavery. Brown went there to help his family and strike a blow for freedom. His participation in the violence and bloodshed in Kansas resulted in the second most controversial period of his life. Brown was convinced that a bold strike at the heart of slavery would do more than fighting slavery on the plains of Kansas. He laid the groundwork for his final campaign at Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia).

On the night of October 16, 1859, John Brown and 21 followers captured the U.S. Armory, Arsenal and Rifle Factory at Harpers Ferry. He called it a “trumpet blast” that would lead to an extended mountain campaign in the slave states and make “property in slaves insecure.” Brown’s so-called raid only lasted 36 hours. He underestimated how quickly white people would rise up to put down what they saw as insurrection. Ten of Brown’s men were killed and five escaped.

Brown was captured on October 18, 1859, by a detachment of U.S. Marines under the command of Army Colonel Robert E. Lee. Brown and six of his men were imprisoned in nearby Charles Town. Virginia seized the opportunity to try “the insurgents.” Brown was soon found guilty of treason against Virginia, conspiring with slaves to rebel and murder. He was hanged on December 2, 1859.

John Brown’s last written words on the day of his execution predicted the Civil War. “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much blood shed it might be done.”