|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Golden Places The History of Alaska-Yukon Mining |

|

CHAPTER 13

Kennecott and Other Mines

Most of the copper mining within Wrangell-St. Elias National Park was done by the Kennecott Copper Company (also known as the Alaska Syndicate). Kennecott's role in Alaska's mining and political history was unique and a matter of considerable controversy from 1905 through 1938.

In addition to Kennecott's activity this chapter also reviews copper and other mining in the Kotsina-Kuskulana district, particularly on Elliot Creek, and the North Midas Mine on Berg Creek.

Discovery

Original location of the huge copper deposits in the region was made by a party formed in 1898 by R.F. McClellan. After failing to find anything worthwhile along the Copper River tributaries in '98, the Minnesota men reorganized for another expedition the following year. In late August 1899 E.A. Gates, acting for the McClellan party, and James McCarthy and Arthur H. McNeer, representing other parties, located the Nikolai group of copper mines on the right limit of the Nizina, a branch of the Chitina Fork of the Copper River about 180 miles east of Valdez. Subsequently, the Chittyna Exploration Company was organized, and more exploration was carried on in 1900 which culminated with the discovery of the Bonanza mines some 20 miles from the Nikolai mines. Controversy erupted over the Bonanza discovery because it was not clear whether prospectors Jack Smith, Clarence Warner, and others were acting for the Chittyna Exploration Company or other individuals who eventually formed the Copper River Mining Company.

Litigation, started in 1902, resulted a year later in a decision by Judge James Wickersham in favor of McClellan and his partners of the Chittyna Exploration Company. This hard-fought legal battle cleared the way for development. [1] The Alaska Syndicate was formed in 1905 through the efforts of Stephen Birch, a bright, determined young man who from 1900-1902 purchased the fabulously rich Bonanza copper claims with backing from capitalist H.O. Havemeyer. Syndicate parties included the banking houses of the Guggenheim brothers and of J.P. Morgan. The Guggenheims, because of their mining experience, directed development of several mines located on tributaries of the Copper River. In 1908 the enterprise was reorganized as the Kennicott Mines Co., then in 1915 as the Kennecott Copper Corp. with Birch as president. The spelling of the new company's name was unfortunate. Someone, noting the proximity of the Kennicott River and Glacier meant to name the company after those places—but the spelling went awry. In this study the community is spelled Kennicott, but it has been spelled both ways over the years.

Smith and Warner, the Bonanza discoverers, had been searching for the source of the copper float reported by Oscar Rohn of the U.S. Army in 1899. Rohn found rich pieces of chalcocite ore in the glacial moraine on the Kennicott River, so the prospectors moved up the Kennicott to National Creek, where they staked claims. Every great mineral discovery spawns its legend, and the Bonanza was no exception. According to their stories, Smith and Warner were eating lunch when they spotted a large green spot on a mountain across the gulch from them. "A good place for sheep," observed Warner. "Don't look like grass to me," said Smith. Their argument over whether it made sense to climb for a look was resolved when they found of piece of rich looking chalconite on National Creek. A scramble up to the "green field" revealed a sensational discovery.

It was in August 1900 that Smith and Warner examined the lode near the Kennicott Glacier, then returned to Nikolai to alert the other nine members of their Chitina Mining and Exploration Company. Soon after, Arthur Spencer of the USGS made an independent discovery. The claims located extended a mile in length along the limestone—greenstone contact at 6,000 feet elevation. The mass of the ore was in the limestone, from the contact to a height of 150 feet along the slope of the hillside, with widths from 2 to 7 feet. Spencer confirmed that "the ore was practically pure chalconite with solid masses exposed from two to four feet across, fifteen or more feet in length and their depth not apparent." A sample showed 70 percent of copper, a good measure of silver, and a trace of gold. [2]

Railroad Development

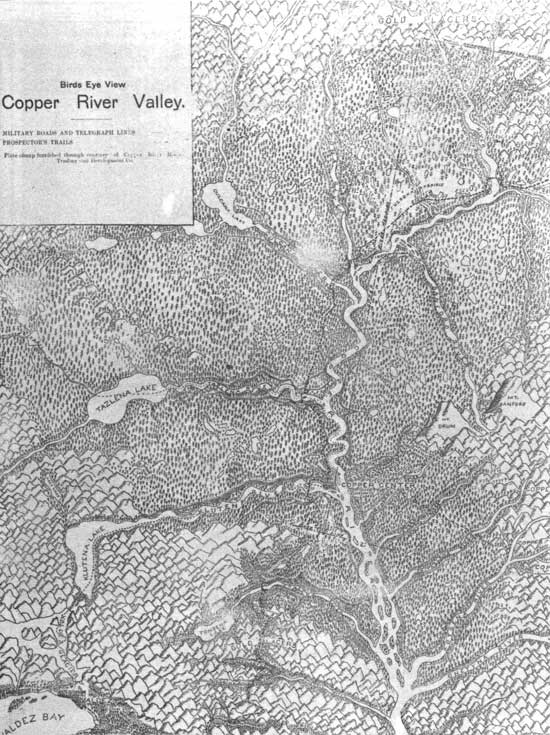

The Guggenheim and Morgan interests realized that they had acquired one of the world's most valuable mineral deposits. They also realized that their holdings were worthless without the construction of an enormously expensive railroad. Engineers examined four different routes for a railroad into the upper Copper River. Two from Valdez would use either the Thompson or Marshall Pass into the Tsaina or Tasnuna tributaries of the Copper, but both involved steep grades. Two more direct routes up the lower Copper started in Cordova or Katalla. The Cordova route did not appeal initially because it entailed the bridging of the Copper River between two active glaciers and laying track over the Baird Glacier's moraine. Katalla's route looked promising, particularly as it, like the Cordova route, would also give access to the Bering River coal fields—assumed to be a resource wealth of immense potential. Katalla's location on an unprotected ocean shore, however, contrasted with the deepwater harbor advantages of both Valdez and Cordova.

The mining business depends on the views of engineers, but this time the syndicate did not get the best advice from its consultants. Initially, construction started from Valdez under George Hazelet. Subsequently, company officers concluded that the Copper River route made much more sense and engineer M.K. Rodgers urged a move to Katalla. Rodgers was sure that he could construct a breakwater capable of protecting ships and a wharf to be constructed on the unsheltered coast. At a cost of $1 million the breakwater and wharf were built but a fierce storm in 1907 swept both structures away. The syndicate abandoned Katalla and the proposed route.

|

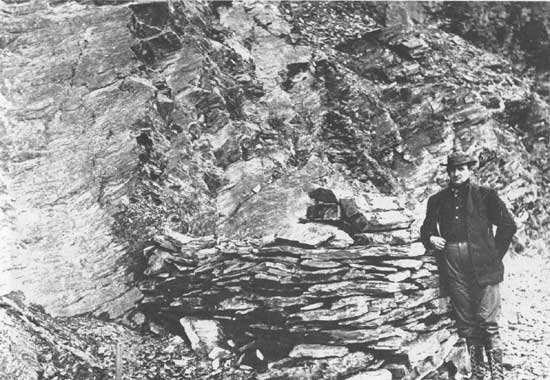

| Ed Hasey's barricade in Keystone Canyon shooting. (University of Oregon) |

|

| River steamboat in Copper River and Northwestern Railway construction. (Washington State Historical Society) |

|

| Copper River and Northwestern Railway. (Alaska State Library) |

|

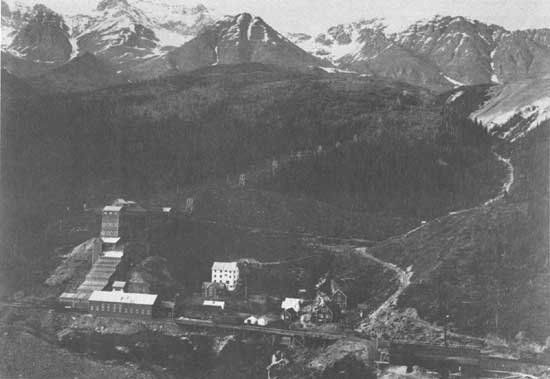

| Kennecott mill. (University of Oregon) |

|

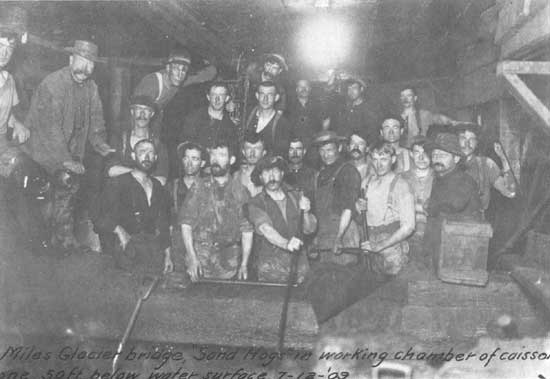

| "Sand hogs" in Caisson Building, Miles Glacier Bridge, Copper River and Northwestern Railway. (University of Oregon) |

|

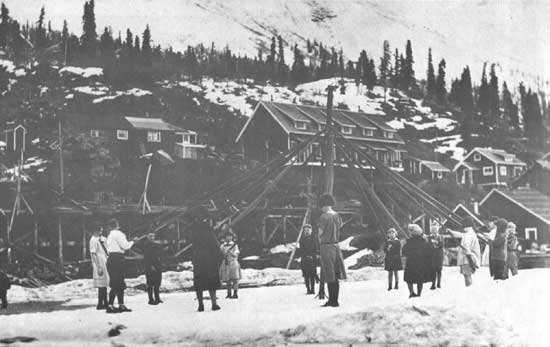

| School at Kennicott. (Wrangell-St. Elias National Park) |

|

| Copper River valley. (Anchorage Historical File & Fine Arts Museum) |

|

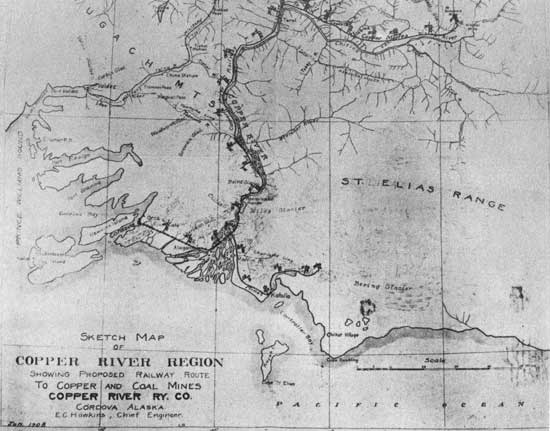

| Copper River region. (University of Oregon) |

|

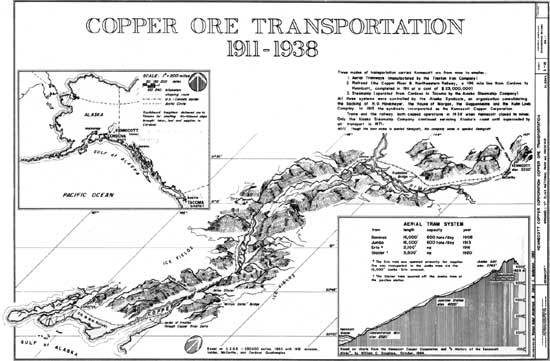

| Copper ore transportation 1911-1938. (National Park Service) |

|

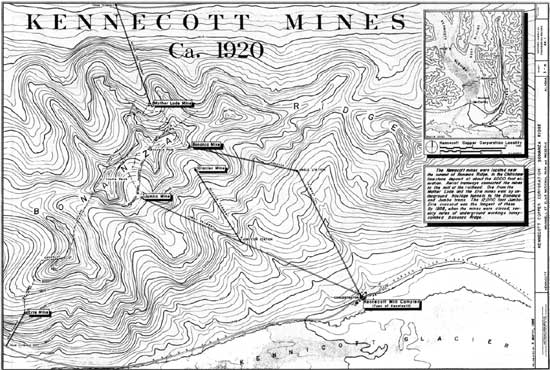

| Kennecott Mines. (National Park Service) |

Michael J. Heney showed better judgment than the syndicate people. Heney, famed for his construction of the White Pass and Yukon Railroad from Skagway, started railroad construction from Orca Inlet (later Cordova) in 1906. Heney expected to sell out to the syndicate when they realized the error of their ways and concluded that his route was the only feasible one. It turned out as Heney anticipated in 1907 after he had pushed the grade work to Alaganik. The syndicate bought out Heney's interest and hired him as grade contractor so he could continue the work. Heney, one of the few Alaska folk heroes, showed his usual drive and organizational genius working for the syndicate but died before the work was completed.

The rejection of the Valdez route by the syndicate encouraged the ambitions of promoter Henry D. Reynolds. Reynolds' place in mining history would be notable even without reference to the railroad rivalry. He was a wily operator of mining, transportation, and other commercial ventures whose ethical sense was perhaps overcome by his magnificent visions. Reynolds first appeared on Prince William Sound in 1901, and by 1907 his Reynolds Alaska Development Company was flourishing through mineral production on the sound and Latouche Island. The syndicate's desertion of Valdez as a rail terminal inspired Reynolds to venture into the railroad field. Money flowed in from Valdez residents who believed that their future prosperity would be determined by a railroad. Investors were encouraged by Governor John Brady's enthusiastic support of Reynold's schemes. Brady, an honest, well-respected man, soon rued the day of his association with Reynolds as the apparent conflict of interest caused his dismissal from office. The interior department secretary was aghast that the territory's chief executive would identify himself with commercial promotion.

Reynolds raised $200,000 for the Alaska Home Railroad in Valdez and arranged for the hiring of workers in Seattle. He also sought additional funding in Seattle and the Northeast, where he sponsored a weekly newspaper to promote company interests. He was no piker, as the purchase of the Alaska Coast Company—a shipping firm, revealed. One thing folks enjoyed about the ebullient promoter was his refusal to be intimidated by the syndicate. In fact, he deliberately antagonized his great rival by sending a ship to Katalla to woo 300 railroad workers away from the syndicate.

In moving too far, too fast, with inadequate financing, Reynolds' railroad venture reached the point of collapse. He tried desperately to get Tacoma capitalists to bail him out but failed. In forfeiting his $100,000 option for purchase of the Alaska Coast Co., he lost the $47,500 already invested. More disastrously, he could not meet railroad construction payrolls. His Valdez bank closed, and Reynolds left Alaska. His efforts to raise money in the East were not successful, and he resigned his chairman's position in January 1908. In April he was indicted for mail fraud on charges of misrepresentations to attract investors. Charges were dropped after he was adjudged insane. [3]

Keystone Canyon Affair

Before Reynolds' fall, he contributed to an instance of corporate violence that marred the achievement of the Copper River and Northwestern Railway's construction. The confrontation in September 1907 between Reynolds' Alaska Home Railroad and the syndicate was perhaps inevitable given the high stakes and the intemperate individuals involved. The Alaska Home Railroad had graded several miles out of Valdez with the enthusiastic support of Valdez folks unwilling to face the death of their hopes for a railroad.

At Keystone Canyon, a narrow defile leading to Thompson Pass along the old Valdez-Eagle road, the Home Railroad crew was confronted by a rock barricade placed by Copper River and Northwest workers. The Home Railroad was on the verge of bankruptcy and its officers resented the interference of the well-funded syndicate road. Since the syndicate had abandoned its Keystone Canyon grade its defense of it seemed surly—and provocative. Of course, the Copper River and Northwest had the legal right to defend its grade against trespass, but this did not extend to the right of shooting trespassers. George Hazelet, a feisty mining man in charge of syndicate operations in the region, tried to awe the trespassers by getting U.S. Marshal George Perry to issue temporary deputy commissions to two syndicate employees, Edward C. Hasey and Duncan Dickson. Hazelet armed the two men and advised them to "be patient, take it cool, but I look to you boys to protect my rights." [4]

Marshal Perry anticipated but could not hold off violence. He wired Valdez Deputy Marshal James Lathrop on September 16: "See that Dickson and Hasey don't exceed authority and get us into trouble." Lathrop responded on September 19: "I am satisfied Hasey has overstepped his authority. Hazelet is not trying to hold canyon but only his grade. I advise you wire Hasey and Dickson to be careful and don't involve this office. Also wire Hazelet to same effect. I look for no trouble over there of any nature. It is simple bluff." [5]

On September 25, the Home Railroad men, armed with tools and clubs marched in a menacing manner onto or near the syndicate's grade and Hasey, sheltered behind the rock barricade with a rifle, shot three of them. Fred Rhinehart later died of his wounds. As most Alaskans denounced Hasey's violent behavior, court officers swiftly convened a grand jury. Governor Wilford Hoggatt hurried to Valdez to investigate the affair. His sympathy for the syndicate was obvious but U.S. Attorney Nathan V. Harlan refused the governor's demands for indictments against the Home Railroad men. The grand jury indicted Hasey for murder and assault but, on the advice of Harlan and his deputy prosecutors W.T. Scott and L.V. Ray, they did not indict Hazelet. At the time, they did not have evidence of Hazelet's instruction to Hasey to "protect my rights."

Hasey's case was transferred to Juneau to avoid the partisanship in Valdez, and to forestall chicanery the Justice Department sent Secret Service agent E.P. McAdams to assist the prosecutors. Reporting in February 1908, McAdams found the atmosphere "terrible," and warned that the jury "will be subject to influences." Alaskans, who traditionally identified New York City and Washington, D.C., as the centers of corruption, would have been amazed at McAdams' opinion of their integrity: "It would take a Constitutional amendment to purify Alaska," he reported to his chief. [6]

Part of the unrest in Juneau grew out of the dismissal of Harlan at the governor's instigation. Within a month of the shooting, Hoggatt had opened his attack on Harlan, blaming him and Scott for failing to prevent the violence and refusing to indict the Home Railroad workers for inciting riot. Hoggatt charged that both men were private counsels to the Home Railroad contractor and that Harlan was a conspicuous drunk. Harlan considered himself a victim of the syndicate for his vigorous prosecution and rallied friends to protest Hoggatt's charges. It does not appear that Harlan was entirely a martyr of the Keystone Canyon shootout because some of Hoggatt's charges, notably those concerning drinking, were confirmed by others. [7]

President Theodore Roosevelt, who always kept a close watch on Alaska events, responded decisively to Hoggatt's charges: "It seems to me Harlan and his sort should be removed at once and steps taken to provide men who will prosecute leaders on both sides in the recent troubles in Alaska, as Hoggatt recommends." Soon after the president heard from the attorney general of Hoggatt's interference in the case and reacted with anger: "It seems well-nigh impossible to be sure that we have got a decent man in Alaska." [8]

As the government's attorneys, John Boyce, William Barnhill, and Scott prepared to try Hasey for murder in Juneau, they were well aware that the attorney general and the president were watching closely. "With an honest jury we can't keep from winning," McAdams assured John Wilkie, chief of the Secret Service. [9] Hasey's defenders, Thomas Lyons of Juneau, John Carson of Tacoma, and Fred Brown and John Ostrander of Valdez, conferred often with Jarvis, Birch, Hazelet, and the syndicate's law firm of Bogle and Spooner in Seattle. Ostrander, the defense team leader, derided Scott and Boyce as "a pair of old grannies," and complained of Judge Royal Gunnison's slow pace. The presence of McAdams, "a bad actor," and "so-called detective" did not awe him: "I think we will be able to show him up."

Ostrander planned to use M.B. Morrisey, a Home Railroad worker, as a defense witness, although he had been subpoenaed earlier by the government. Morrisey seemed eager to testify that some of the Home Railroad men had been armed so the prosecutor had no use for his testimony. "Morrisey is acting on the square," Ostrander believed. The true role of Morrisey later taxed investigators of the trial. It was not his testimony, which had corroboration by other defense witnesses, that aroused suspicion, but his open-handed entertainment of and loans to other defense witnesses. Morrisey spent money provided by the syndicate and drew a salary from it during the trial and afterwards until he departed for parts unknown. [10]

The trial opened in April 1908. Ostrander's confidence was not diminished by the sudden illness and death of Assistant U.S. Attorney Scott, or even the hostility of Judge Gunnison, "the most ignorant fool that ever sat on this or any bench." After several weeks of trial, jurors found that Hasey's apprehension of bodily harm from the Home Railroad gang justified his shooting and acquitted him of second degree murder charges. The government persisted, trying Hasey for assault with intent to kill in February 1909. This time jurors decided that Hasey's gun play had been unnecessary and unreasonable and found him guilty. Judge Gunnison sentenced him to 18 months at the McNeil Island, Washington, prison. Initially, Hasey's attorneys prepared to appeal, then dropped it when syndicate officers encouraged Hasey to serve his time in return for receiving his full pay and other benefits. According to rumor the syndicate followed this course because of Morrisey's persistent demands for money. [11]

With Hasey in jail and the Alaska Home Railroad bankrupt and disgraced because of questionable activities by its promoter, the syndicate's reputation improved. Construction of the Copper River and Northwestern Railway and other developments captured public attention. Michael J. Heney, "the Irish Prince," was the railroad contractor and a universally admired figure. Heney had built the narrow-gage White Pass & Yukon Railroad from Skagway to Whitehorse during the Klondike gold rush. The new railroad was a greater challenge because of its far greater length, wider gage, and the formidable obstacles posed by huge glaciers. It also answered a long-expressed desire of Alaskans for an "all-American" route to the interior. Syndicate officers often declared their intent to carry construction of the railroad all the way to the Yukon River to achieve a combined rail-river route that would aid territorial development. Whether the syndicate was ever genuinely interested in building beyond Kennicott is not clear, but when the line reached the copper mines in 1911, construction ended.

Railroad Construction

Construction plans called for a single-track, standard-gauge railroad running 131 miles to Chitina from Cordova; then branching to extend 65 miles to the Kennecott mill. The route from Cordova was south and east across the outwash from the Sheridan Glacier to Alaganik, a western slough of the Copper River, then northeast to the main channel of the Copper River delta. The first bridge was constructed at mile 27. The line crossed the delta to mile 39, Katalla Junction, then turned north for 10 miles and its main crossing of the Copper at mile 49. Following the right limit of the Copper, it ran through Abercrombie Canyon, across Baird Glacier moraine and the Aken Glacier outwash to the confluence of the Tasnuna and Tickel rivers. Thence, the line entered Clay Wood Canyon and followed the Copper to Chitina.

Local hemlock was cut for rail ties, and 70-pound steel was used for the Cordova-Chitina line. From Chitina, 60-pound steel was used for the rest of the route. From Chitina, the line crossed the Copper and continued east on the north side of the Chitina River. As with the steel weight, construction standards were reduced for the Chitina mill route. From Cordova the maximum gradient was 0.5 percent and the maximum curvature was 10 degrees; from Chitina 2.5 percent grades and 14-degree curves were permitted. E.C. Hawkins, another veteran of the White Pass and Yukon Railroad project, was the chief engineer in charge of railroad construction. [12]

Bridge building, particularly that of the "million dollar bridge" at mile 49, provided the most dramatic highlights over the 1907-1911 construction period. In the summer of 1909 Hawkins and A.C. O'Neil, superintendent of bridge construction, took on the formidable task of bridging the 1,500-foot channel at mile 49 where the Copper flowed between the Miles and Childs glaciers.

The project was unique because of the glaciers' impact. Just a mile above the crossing, the 3-mile front of the Miles Glacier discharged a valley of icebergs from early spring through late autumn. The largest of these icy behemoths weighed thousands of tons and coursed downriver with a 12-mile current. Somehow the ice had to be diverted while the bridge was constructed. Once in place the bridge had to be protected from the annual spring river breakup, when ice frozen to depths of 7 feet would be loosed to smash against any structures in its way.

Construction started with three giant piers sunk 50 to 60 feet to bedrock. The piers, with their greatest diameter at 86 feet, were solid concrete armored with steel rails to better withstand the impact of ice. Work was done after freeze-up to avoid ice movement. With the piers in place, work proceeded rapidly in April and May in a desperate race to complete the structure before breakup. All the necessary timber falsework rested on the river ice, and a disaster was narrowly averted when, after a series of fierce storms, the river began to rise, lifting its 7-foot ice cover and the bridge falsework with it. All hands worked furiously to thaw and cut out ice from around the piles to prevent pressure on the falsework. Despite these efforts, the cantilever construction falsework of the third pier was driven 15 inches out of line. Hawkins, through a herculean effort, managed to force the 450 feet of heavy piling and substructure back into line with tackle rigging. Bridge work was then pushed forward and all the work was completed just two days before breakup. [13]

Construction support and transport of materials was aided by the service of a steam sternwheeler, Chitina, assembled on the Copper in 1907. Two other steamers were built in 1907-1908. Much of the material and provisions had to be transported during the winter by horse-drawn, double-ender sleds until construction permitted operation of a supply train. An incident in 1909 illustrates the vicissitudes of winter construction—the blockage of a work train by snow for 21 days. The 160 men aboard the train had to wait out the storm before they could start digging their way from beneath a mountain of snow. [14]

At the peak of railroad construction, 6,000 men labored on the project. Excavation totaled 5,180,000 yards, more than half of which was solid rock and embankments placed comprised 1,200,000 yards. Fifteen percent of the 196-mile railroad was built on bridges or trestles with 129 bridges between Cordova and Chitina. Of these bridges five were major steel structures totaling 4,000 feet. Construction cost $23,000,000.

Geologist Alfred H. Brooks did not exaggerate in calling the completion of the railroad "the most important advance made in the history of Alaska transportation since steamboat service was established on the Yukon." [15]

Cordova

Valdez did not fade away because it did not get a railroad but Cordova developed into a substantial town. Cordova's site had been the old Indian village of Eyak and a cannery location before it was designated the railroad terminal. Its natural features include a good harbor, plenty of level ground, and its location—only 20 miles from the mouth of the Copper River. By 1909, a year after its founding, 1,500 people lived in Cordova, served by 10 stores, two hotels, two lumberyards, three churches, 10 saloons, and a school. Cordova's interests were bound to the railroad and to the syndicate.

Nominally, Cordova was an independent community, but it resembled a company town in many respects. The local newspaper, the Cordova Times, supported the syndicate and attacked anyone who criticized the Kennecott Company. As with other mining towns, the editors boosted Cordova constantly and viewed the community's economic future as one of boundless potential. George Hazelet, the first mayor and townsite developer, was a syndicate man. Nevertheless, he exhibited a somewhat restrained view of the town's future. Eventually, he told a reporter in 1909, Cordova will have 5,000 to 10,000 people supporting the mining and transportation industries, but 1,500 was plenty at the time: "No greater misfortunes could befall the town than a large influx of people before this is warranted by the permanent development of the country." [16]

Even in its raw beginnings, Cordova offered some amenities, including places to eat, drink, and gamble. For those who did not like saloons, there was the clubroom of the Episcopal Church, which was supervised by E.P. Ziegler, later a famed painter. Men could play cards, shoot pool, smoke, drink coffee, and read magazines without any obligation to attend church services.

Among the interesting shops in town was the photograph studio of E.A. Hegg. Hegg's photos of the Klondike stampede are among the best-known pictures of that event. After the Klondike rush, Hegg went Outside for a time. Later, he returned for employment as photographer on the construction of the Copper River and Northwest Railway, then ran a studio in Cordova.

Cordova, of course, survived the closing of the Kennecott operations and the end of the railroad. Its modern economy depends upon fishing and the burgeoning recreation and tourism industry.

McCarthy and Chitina

McCarthy, 150 miles inland from Cordova, developed into a small community in 1908, serving the railroad and Kennecott mining interests. About 4 miles from Kennicott, its facilities provided some relief for mine and mill workers who preferred recreation away from the company town. The town's peak population in the 1920s was 127. A few of these were prostitutes, who were not allowed at Kennicott. McCarthy survived the closing of the Kennecott operation to exist in a ghostly fashion and even survived the loss of the bridge that linked it to the Edgerton and Richardson highways, but it has been home to few since the 1920s.

A town's fading from a vital community to a marginal one is signalled by many events, but the closing of the school is certainly strong evidence of decline. In December 1931, while Kennicott was still going strong, the commissioner of education closed the McCarthy school which then had only two pupils. McCarthy's weekly newspaper, the News, published from 1917 to 1928. [17]

Chitina, a railroad town 100 miles inland from Cordova on the Copper River, was another small community that gradually died after Kennecott shut down. It functioned as a transfer point for a stageline that connected Chitina with Willow Creek Junction on the Valdez Trail. Quite a few Indian families made their homes at Chitina during the railroad era.

O.A. Nelson, who quit teaching school in Missouri to take up railroading, took a surveyor's job with the Copper River and Northwest Railway in 1908, then settled in Chitina. Forty years later he was one of its few residents. He recalled many things that made life singular in Chitina. One was the spring rite of watching the ice movement at breakup destroy the wooden trestle bridge which spanned the Copper and Chitina rivers. After 1939 this annual destruction ceased because the bridge was no longer rebuilt. [18]

Evaluating Copper Ore

According to legend, the visible wealth of the copper lodes developed by Kennecott had been obvious to beholders for years prior to their actual mining. In fact, W.E. Dunkle, a mining engineer employed by Kennecott in the company's early years, found that determining the lode's value was not easy. Company experts made a microscopic study of the Kennecott chalcocite—the main ore body—which resulted in a wrong assessment of its value. Their investigation "seemed to show that the copper glance was secondary after bornite." At the time, around 1912, the only mining that had been done on the Bonanza fissure and the rich cliff outcrop ore body of glance pinched out at 300 feet. Little work had been done on the parallel Jumbo fissure, and nothing on the surface indicated the enormous ore bodies that would be found there.

Dunkle believed that rich ore veins would be discovered eventually, but Kennecott's management disagreed and accepted the more pessimistic view, concluding that the rich ore was secondary. As a consequence the company, deeply in the red because of railroad construction costs and only beginning to ship out ore, passed up the chance to buy the Mother Lode Mine at a modest price. Mining proceeded and eventually Dunkle's prognosis was proved correct. Later, Kennecott had to pay a heavy price for a joint mining agreement with Mother Lode owners. [19]

Kennecott Production

With completion of the railroad in 1911, the syndicate's heavy investment finally began to pay off. Mining and milling had been going on for some time, and the loading dock at the mill was full of ore. To reach the main adit level of the Bonanza Mine at 5,600 feet, workers either hiked a 4-mile trail or rode the bucket tramway. Miners much preferred riding the aerial tramway to walking, despite the risk. The Bonanza tram was capable of moving 1,000 tons of ore a day to the mill. Some high-grade ore was shipped out directly, most passed through the mill for concentration. Further processing of mill tailings followed in the beaching plant, which could treat 600 tons a day. Equipment for a 400-ton mill, the tramway, the power plant, and other structures had been transported from Valdez by pack horses and sleds long before the railroad was completed. By that time the first mining tunnels had been driven into the Bonanza and Jumbo mines, and each had its own aerial tramway. The Jumbo tramway, extending 16,000 feet, was the second one built and began operation in 1913.

By 1916, with high war prices encouraging production, the mines and mill were operating around the clock with three shifts of workers. Each tramway carried 400 tons of ore each day. Most ore was low grade, averaging 7.5 percent copper, but the Jumbo mine's output of high grade, 70 percent copper, was almost half of its yield.

William Douglass's comparison of the Kennecott operation in 1916 with the famed Anaconda Mine of Butte, Montana, is illuminating. At Butte, there were 30 shafts, some down to 4,000 feet, equipped with fast, modern hoists. Anaconda employed 15,000 men to produce 30,000,000 pounds of copper each month. By contrast Kennecott had two small mines being worked "through single compartment incline shafts. Its hoisting equipment was of modest scale and low powered. The total payroll of mines, mill, and surface staff was only 550 persons yet Kennecott produced 10,000,000 pounds monthly—one-third of Anaconda's output." At the time, in 1916, Kennecott did not have a large reserve. Bonanza was fading but the Jumbo ore was wonderfully rich "solid chalcocite for a stope length of 350 feet, with a width of 40 feet and a height of 40 feet." That block produced 70,000 tons of 70 percent ore, which also included 20 ounces of silver per ton. [20]

Maintaining year round operation of the railroad, mine, and mill was a formidable responsibility. Heavy snows sometimes taxed the abilities of railroad crews, despite use of the largest rotary snowplows made. Heavy storms hindered mill-mine operation at times, as in spring 1919 when communication between mines and mill was disrupted for several days when slides wiped out telephone lines, demolished tramway towers, and closed trails. Slides at the Mother Lode threatened bunkhouses and forced miners to live in the mine tunnels for several days.

In 1919 the company formed the Mother Lode Coalition Mines to mine and mill the valuable ore located between McCarthy Creek and Kennicott Glacier. The Bonanza tramway transported ore from the Mother Lode to the mill. Passages between the Mother Lode and Bonanza and Jumbo mines provided for efficient movement of miners underground. [21]

The Erie was the fourth mine of the Kennecott group. It perched high in the cliffs above the Kennicott Glacier, 4 miles north of the mill. It was connected to the Jumbo by a 12,000-foot crosscut. Erie's production did not compare in volume with that of the other mines, but it helped maintain production after Jumbo reserves dwindled and served to justify an expansion of the tramway and mill in 1920. Tramway capacity was increased to 600 tons and the mill's to 1,200 tons daily.

Production statistics from 1901-1940 summarize the rise, flourishing, and decline of the industry. Note that the following production statistics include output of all Alaska's copper mines. Kennecott and the mines of Prince William Sound (see Chapter 7) contributed 96 percent of the total. Prince William Sound production amounted to 214,000,000 pounds from 1904-1930.

Copper Provided by Alaska Mines, 1901-1940 [22]

| Year | Pounds | Value | Year | Pounds | Value |

| 1901 | 250,000 | $ 40,000 | 1921 | 57,011,597 | $ 7,354,496 |

| 1902 | 360,000 | 41,400 | 1922 | 77,967,189 | 10,525,655 |

| 1903 | 1,200,000 | 156,000 | 1923 | 85,920,645 | 12,630,335 |

| 1904 | 2,043,586 | 275,676 | 1924 | 74,074,207 | 9,703,721 |

| 1905 | 4,805,236 | 749,617 | 1925 | 73,855,298 | 10,361,336 |

| 1906 | 5,871,811 | 1,133,260 | 1926 | 67,778,000 | 9,489,000 |

| 1907 | 6,308,786 | 1,261,757 | 1927 | 55,343,000 | 7,250,000 |

| 1908 | 4,585,362 | 605,267 | 1928 | 41,421,000 | 5,965,000 |

| 1909 | 4,124,705 | 536,211 | 1929 | 40,510,000 | 7,130,000 |

| 1910 | 4,241,689 | 538,695 | 1930 | 32,651,000 | 4,244,600 |

| 1911 | 27,267,878 | 3,408,485 | 1931 | 22,614,000 | 1,877,000 |

| 1912 | 29,230,491 | 4,823,031 | 1932 | 8,738,500 | 550,500 |

| 1913 | 21,659,958 | 3,357,293 | 1933 | 29,000 | 1,900 |

| 1914 | 21,450,628 | 2,852,934 | 1934 | 121,000 | 9,700 |

| 1915 | 86,509,312 | 15,139,129 | 1935 | 15,056,000 | 1,249,700 |

| 1916 | 119,654,839 | 29,484,291 | 1936 | 39,267,000 | 3,720,000 |

| 1917 | 88,793,400 | 24,240,598 | 1937 | 36,007,000 | 4,741,000 |

| 1918 | 69,224,951 | 17,098,563 | 1938 | 29,760,000 | 2,976,000 |

| 1919 | 47,220,771 | 8,783,063 | 1939 | 278,500 | 30,000 |

| 1920 | 70,435,363 | 12,960,106 | 1940 | 122,369 | 13,800 |

| TOTAL | 1,373,764,701 | 227,419,199 | |||

Peak and Decline

Though 1916 was Kennecott's best year, historian Melody Webb has described 1923 as the "pivotal year" for Kennecott—the year that its slow decline commenced, although production reached its highest point. Production was high in 1923 because the post-World War I slump caused by overproduction and low prices finally ended. But the high level was not maintained; it fell sharply in 1924-29 as high-grade ore sources were depleted. The Bonanza and Jumbo mines had been declining since 1918, but the Mother Lode produced well, and another ore body was discovered on the Jumbo-Erie crosscut. [23]

Superintendent William C. Douglass aggressively pursued a higher yield by mining the Glacier Mine and installing new technology. Technical innovations included the construction of a leaching plant in 1922-23. Developed at Kennecott by E. Tappan Stannard in 1915, the ammonia leaching process was a significant advance in technology. Its success led to its use elsewhere in the industry. Chemicals were used to dissolve the mineral from low-grade ore, then precipitate it into a concentrate. The leaching process was completed in flotation tanks "when oil or grease was used to separate, through a bubbling action, the mineral from its host rock." [24] Litigation between the process patent holder and other western mining companies had delayed the construction of Kennecott's leaching plant. The process worked well at Kennecott, allowing a recovery rate of 96 percent, but the scarcity of water over the winter restricted its use. [25]

A detailed statistical breakdown for the company operation exists for the year 1924, when 550 men were employed. Of the 321 working in the mines, 146 were in the Mother Lode. Highest wages, $5.50 to $5.75 daily, went to the electricians and machinists; skilled mill men earned up to $5.50, while miners got $5.25 and laborers $4.25. [26]

Douglass, like other superintendents, was intolerant of union men. All new employees were required to swear that they were not union members and promise that they would not join a union while employed by Kennecott. Wages were pretty good for the early 1920s. A 1923 contract stipulated a $4.60 daily wage, less board of $1.45 daily and eight cents hospital dues. Employees who were hired in Seattle were advanced the $37 charged for ship fare to Cordova, which could be gradually repaid from wages. Even the railroad ride on the syndicate's railroad was only conditionally free: the $23.40 fare was advanced and deducted from wages until six months satisfactory employment was completed. At that point, any deductions were repaid and no others were taken. [27]

The 550 employees in 1924, divided between the mill (249) and the mines (321), earned a monthly total of $86,337. It cost 8.23 cents a pound to process the ore for copper (aside from the gain from the silver extracted from the ore), and reserves were dwindling. Earlier high-grade ore assayed at 75 percent; now the Bonanza-Jumbo ore was 50 percent and that of the Mother Lode about 60 percent. Copper prices averaged 14 cents a pound from 1924-28 and rose to 24 cents in 1929, but Kennecott's limited reserves did not enable the company to take full advantage of the boom. Low prices rather than low grades were the chief factor in the company's decline and end.

Life at Kennicott

The company town of Kennicott (Kennecott) was laid out beside the Kennicott Glacier. As was mentioned, the different spellings for the glacier/river and town company is an irritating memorial of careless spelling. (Modern maps show "Kennicott" as the townsite name, but earlier maps spelled it "Kennecott.") Kennicott was the name given to glacier and the river by U.S. Army explorer Oscar Rohn to commemorate Robert Kennicott, leader of the scientific corps of the Western Union Telegraph Expedition of 1865-67. Located about 4 miles from McCarthy, the town's elevation is 2,200 feet. At its peak in 1920, Kennecott had a population of 500, including the majority of miners who lived in buildings near the mines high above the town and mill.

We have some interesting documentation on the society of Kennicott, including memories of school days in the 1920s written by Superintendent William Douglass' son. Youngsters from some 20 families of the community attended a two-room school through the eighth grade. For secondary education they were sent to Cordova or Outside. Ice skating and hockey were the chief school recreations. The two teachers worked students hard, although a winter carnival in March provided some relief. The teachers, like the town's two nurses, were usually young, single women "who lived in the staff house—and were almost always married during that year, requiring replacements, because there were lots of single men." [28]

Most of the town's residents enjoyed socializing. Movies were shown on Wednesday and Sunday nights in the town hall. On days like New Years Eve, live music was arranged for dancing. During the summer, baseball was popular, as was fishing. Almost everyone hunted some in the fall. Summer fun also included the year's biggest celebration, Fourth of July, held in McCarthy.

The company took advantage of its isolated location to protect against contagious diseases. All new employees were required to spend several days at a camp outside of town to reduce the risk of bringing in disease.

Religious services were conducted in the schoolhouse whenever a priest or minister from Cordova appeared. Reading was popular. A lending library supplied the latest fiction, and many residents subscribed to magazines which were handed around. Shopping was easy since most of it was done through the much-studied mail order catalogues of Sears, Roebuck or Montgomery Ward. Foodstuffs, mail, and catalogue orders arrived by train although there were a few vegetable gardens in the summer and the company's dairy supplied butter and milk.

Life for the men who lived in bunkhouses was more restricted than that of families, who had small houses, but it was not unpleasant. Mining engineer Ralph McKay recalled the long winter evenings in the bunkhouse at the Bonanza Mine in the 1920s as serene. Despite the men being of mixed nationalities, "they weren't restless and arguments were few. Some played poker while others were busy at blackjack." Some studied catalogues or read newspapers while others listened to an old hand-crank phonograph. Radio signals could not be heard at Kennicott. [29]

Ernie Goulet was another miner who recorded his experiences. He walked most of the way from Cordova to Kennicott in the winter of 1930-31 because heavy snowfalls shut down the railroad. He got a job at the Jumbo Mine which was 4 miles and 4,000 feet above the Kennecott mill. Before taking the 45-minute ride by tramway he had to waive any claim against the company for accidents. The two Jumbo bunkhouses housed 80 men each in two-to-four-men rooms. A small gym and pool table were leading recreational features. He liked his fellow workers but quit when company economy measures dictated a 10 percent wage cut. [30]

Fred Hoff went to work as an assayer in 1935. He was one of the lucky bachelors there to find a bride—a company nurse. The couple moved from staff houses to an apartment above the company store. Life was not too hard but job security was a worry during the depression. The Hoffs would have liked to save money, but food costs were high. Ice, however, was free from the nearby glacier. [31]

Some miners liked working at Kennecott because unlike most mines, it provided work for the full year. Others used their employment to put away a stake to support their own prospecting or mining. Some men spoke well of Kennecott's management, and others did not. The company did seem to provide for workers and their families, medical, recreational, and educational needs, but employees were wise to remember that its policies were dictated by self-interest. No one ever accused the company of outright benevolence to employees, but it met the standards of the day and achieved its corporate goals.

Accidents

Individuals who recorded their impressions of Kennicott all mentioned particular accidents. Some were acts of nature, like winter snow avalanches, but more common were accidents in the mines, the mill, or in the tramway.

As a major employer in a hazardous enterprise, Kennecott frequently was sued by workers who suffered injuries. When Ernest VandeVord, a line repairman, was thrown from the moving bucket line running from mine to mill and fell 40 feet to jagged rocks below, he suffered a permanently stiff wrist and back. The company argued that workers assumed all risks in riding the buckets. VandeVord's attorney countered that a defect on the line caused the accident. Jurors awarded the 25-year old machinist (who had earned $90 a month), $750 rather than the $20,000 he asked. The company tried unsuccessfully to have the award set aside. In other respects Kennecott also showed stinginess. When VandeVord asked his foreman about wages, he was told "there is a new rule existing here. When a man gets hurt, his time stops and as soon as he gets out of the hospital, he has to pay board. In your case Mr. Emery will see you—and make some kind of settlement." [32]

Any litigation involving the company was generally tried in Cordova when the third district court, based in Valdez, convened periodically. Records indicate that in disputes with employees Cordova jurors usually favored the company. Occasionally, an employee requested a change of venue, as did Daniel S. Reeder, who was injured in a railroad tunnel cave-in in 1913. The company successfully resisted the change, arguing that the absence of other employees needed as witnesses would hamper operations. [33]

James Heney, another railroad worker injured by a tunnel cave-in while digging out a previous cave-in, asked $25,000 for the permanent crippling of his hip when timbers crushed him. His award was only $2,125. [34] A jury drawn from residents of Seward and Valdez was more generous in compensating the estate of E.A. Reed, railroad engineer. Reed died when his locomotive fell through a bridge that had been partially burned but not repaired. The award was $20,000. [35]

Cordova folks were not prudish and were consistent in favoring the company in other kinds of cases, as Matilda Snyder discovered when she sued George Hazelet in 1912. Hazelet, a company executive and town founder, owned a building that accommodated a bawdy house that offended Snyder because her laundry was located next door. Hazelet effectively resisted her claim for damages, showing that she had deliberately established her laundry next to the bawdy house "to get the business." [36]

During the railroad construction boom, the company had more options in settling litigation. J.E. Dyer, operator of a pile driver, suffered a permanently crippled leg in a construction train accident. He sued for damages then desisted when the company gave him a small settlement and permitted him to run an unlicensed saloon and gambling place at Tiekel. Unfortunately, Dyer liked his own goods too much: "He spent all his money from both sources," his lawyer said, "as rapidly as he could in drunkenness and riotous living." When his money was gone Dyer pleased everyone by "disappearing from Alaska," thus abating "a public nuisance." [37]

Closing Down

The end of Kennecott was foreshadowed by depression events. Copper fell to five cents a pound in 1931. The company halted use of its expensive leaching process but still lost $2,000,000 that year. Further disaster occurred when a railroad bridge washed out in October 1932, causing the company to close the mines in 1933-34. Reporting on Alaska's mineral industry in 1933, Philip S. Smith of the USGS spelled out the obvious:

It must be remembered that the mines near Kennecott, which have contributed perhaps ninety percent of the Alaska copper, have been mining a unique deposit, not comparable with any other known deposit in the world, so that inevitably their mineral wealth is being depleted and there is no justification for expecting that their loss will be offset by new discoveries of equally marvelous lodes. [38]

In terse fashion, the company's annual report for 1938 told the story:

The Alaska property was operated until the latter part of October when all ore of commercial value was exhausted and the property closed down. Equipment having any net salvage value was removed and shipped out before abandonment of railroad properties.

The report went on to explain:

Production from this property has averaged only 525 tons copper per month since 1928 and therefore cessation of these operations will not affect earnings as this tonnage can easily be made up from other properties [outside of Alaska]. [39]

Overall, 4,626,000 tons of ore, averaging 13 percent copper, were mined. From this ore, smelting produced 591,535 tons of copper and 9,000,000 ounces of silver. According to William Douglass, the company netted $100,000,000 profit on the $200 to $300 million in ore sales. Among the great copper mines of the world, Kennecott ranked 11th but no other surpassed or equaled it in the high mineral content of its ore. [40]

Small lots of high-grade chalcocite ore have been intermittently shipped from the Kennicott area since 1938. State records indicate that 32 tons of copper ore were shipped from there in 1965. All shipments were flown by DC-3 to Glennallen by a small operator.

The impact of Kennecott on Alaska's development cannot be measured by production statistics. Its importance in the territory's economy can not be exaggerated. Kennecott's operation commenced as placer gold production in several regions of Alaska was declining. Its large investments heralded a new era of corporate expansion and provided a much-needed payroll for many years.

The Kotsina-Kuskulana District

The Kotsina-Kuskulana district lies in the west end of Chitina Valley on the southwest slope of the Wrangell Mountains. Though small, 16 miles long and 12-1/2 miles wide, it was considered for many years to be rich in potential for copper and possibly gold and silver as well. As it turned out, the region is the best Alaska illustration of disappointment following long-proclaimed expectations of wealth.

What kept the focus on the region's potential for so long was its proximity to the Kennecott mines some 20 to 30 miles away and the resemblance of its mineral formations to those of the fabulously rich Kennecott group.

Government investigation of the district began with Oscar Rohn in 1899, followed by USGS surveys in 1900, 1902, 1907, 1912, 1916, 1919, and others. Traversing the mountainous terrain was difficult and treacherous. The valley floors of the Kotsina and Kuskulana are at 2,000 to 2,500 feet, and surrounding peaks rise from 5,000 to 7,395 feet. Most of the valleys tributary to the Kotsina and Kuskulana are hanging valleys, so-called because their mouths are above the level of the main valley floors and can be entered only after a steep climb of several hundred or a thousand feet.

Access to the district remained difficult even after the construction of the Copper River and Northwest Railway. Even in the 1920s prospectors still sledded in their provisions over the winter. Mail and small items could be brought in from Strelna over summer trails via Rock and Strelna creeks or by Roaring and Nugget creeks. Miners called for a wagon road down the Kotsina River to Chitina or some other point on the railroad but did not get it. Most of the claims still active in 1922, when Fred H. Moffit and J.B. Mertie, Jr. of USGS investigated the district, were on tributaries some distance from the Kotsina. Among these were the Cave, Peacock, Mountain Sheep, and Blue Bird claims on Copper Creek. Others on Amy, Rock, Lime, Roaring, and Peacock creeks, the Sunrise Creek group and the Silver Star group (considered valuable for silver rather than copper) were owned by Neil and Thomas Fennesend.

Among the Kotsina River claims those on Elliott Creek (see Chapter 2) were "more widely known than any other copper-bearing locality in Chitina alley except Kennecott." Here as elsewhere miners had done much tunneling—some tunnels exceeded 1,000 feet—searching for valuable copper ore. [41]

North Midas Mine and Others

Prospects on Berg Creek, a tributary of the Kuskulana River 12 miles from Strelna, were staked by the North Midas Copper Company in 1916. Earlier claims on the ground had expired for want of recent assessment work. The Midas company went to work on tunnels and was soon mining ore from two levels reached by separate adits. In winter 1918 a carload of gold ore was shipped out, and that summer a mill, crusher, and cyanide plant were installed. A Roebling cable tram 4,600 feet long and capable of carrying 5 tons an hour connected the mine to the mill. Production in 1919 was only 40 ounces of gold and 513 ounces of silver. The mill was shut down in 1925.

Geneva Pacific Corporation became interested in the North Midas and other copper claims in the 1970s. Other claims included the Nelson Mine, one that Kennecott tried to develop in the 1930s and the Binocular Prospect developed by pioneer prospector Martin Radovan. [42]

Radovan came to Alaska to work on the Copper River and Northwestern Railroad and later mined placers on Dan Creek and lode on Glacier Creek. His greatest feat was in staking a group of claims on Binocular Prospect near Glacier Creek. The existence of a large copper stain high on the face of a steep-walled recess in the mountains, had intrigued prospectors for years. No one had been able to reach the stain, but many scanned it with binoculars—hence the name.

After several unsuccessful attempts to reach the remote face, the Kennecott Copper Corporation got serious about it in 1929. It hired several expert mountain climbers, but they called it quits without succeeding after a summer's effort.

Meanwhile, Radovan climbed to a gulch just north of Binocular Prospect and put in a hazardous week cutting steps hundreds of feet along the face of the cliff until he reached a point 200 feet below the Binocular stain. From this point he scaled the wall using ropes and drill steel driven into rock crevices. Radovan staked claims and did some work before giving up working the difficult site.

Geneva Pacific purchased the claims from Radovan before he died in 1975 at the age of 92. The company hired a mountain climber who helped workmen reach the site to prepare a helicopter landing place. Investigation of the claims was then easier.

The prospect proved not to hold the mineral riches that Radovan and the company had hoped. Title to the claims was donated to the National Park Service in 1985. The 250-acre donation included 18 mining claims, six millsites, and a number of buildings.

Hubbard-Elliott

Philip Smith of the USGS was right in his 1933 speculation that no other rich copper lodes would be found in Alaska. Efforts were made from 1900 to the 1930s, but no other "marvelous lodes" were discovered. It is part of the Kennecott legend that the syndicate refused to develop all the copper available in the region because of a greater commitment to copper properties owned outside Alaska. As recently as 1964, Charles G. Hubbard, then in his 90s, a historian that Stephen Birch, the longtime head of Kennecott, was ruthless and unscrupulous and refused to develop claims Hubbard offered for sale. But the record of the Hubbard-Elliott holdings suggests that both Hubbard and his partner, Henry Elliott, did well with their copper claims. The prospectors had entered the Copper River country in 1897 but did not discover their significant copper prospects until 1901. They located on Elliott creek, a Kolsina tributary and, finding other prospects in 1902-1904, prepared to reap a fortune.

The partners' Hubbard-Elliot Company attracted some attention nationally. Publicity helped miners draw investors, so Hubbard and Elliott were pleased by a full page spread in the Chicago Record-Herald, including pictures and full acquiescence in their estimates of potential. "Fabulous Wealth Strike . . . Copper claims covering four miles of territory . . . the ore in sight, at present market prices, is $112,000,000, but it may reach a billion dollars or even more," were heads topping a grand story. The reporter described the partners of the '97 crossing of the Valdez Glacier, their travails in a scurvy-ridden winter camp, and two years of fruitless search for gold before they stumbled on a mountain of "boronite, black oxide, glance, gray and native copper . . . the richest large body of ore yet discovered." Hubbard and Elliott did confess that marketing their ore, which would "run 50 to 70 percent copper" posed a problem—"a cloud to this dazzling prospect of wealth: there are no means of transporting the ore to the coast for shipment to the mills." Yet railroad talk was in the air, and perhaps a line would be built within two years. Until then, the partners would "work their claims and get ready for the hoped-for railroad." [43]

The fortunate partners alleged that "experts" had confirmed their high estimation of Elliott Creek ores, but the first "experts" were followed by others over the years. One such, an engineer who wrote anonymously, was sent in 1904 from Cedar Rapids, Iowa, to Seattle and Valdez from whence more difficult travel commenced. From Valdez, the engineer traveled with a packhorse outfit, leaving town on July 27, following "the new railroad right of way," then the government trail through the "Lowe River Canyon" (Keystone Canyon), on a trail "narrowed down to only a few inches along the side of the mountain . . . on our left was a wall hundreds of feet, on our right, sheer precipices hundreds of feet." A magnificent waterfall 600 feet high awed him as the party moved on, reaching Camp Wortman in the evening. Out of Wortman's, the rough trail was dangerous with mud and snowdrift. One horse slid down 200 feet on its side. At Beaver Dam Roadhouse, "run by two old maids from Boston," the travelers refreshed themselves, then pushed on to Earnestine on the 30th and Tonsina on the 31st. They made 25 miles the next day to reach the Copper River, crossing on Doc Bellum's ferry.

Finally, on August 5, they reached Elliott Creek to enjoy bunks in the Hubbard-Elliott cabin and "first class grub." Next morning, the engineer visited the Albert Johnson, Guthrie, Marie Antoinette, and Elizabeth claims. Miners were using a diamond drill on the Elizabeth: "we saw enough ore in sight to keep a railroad busy and of the finest quality." Another anonymous "expert" also showed up to confirm "the finest proposition he ever expected to see." The visitor gathered samples from several mines, then relaxed to hunt, fish, and read—when the weather was bad. Later in August, Stephen Birch appeared, looked at the ore samples "and said they looked good." The cut on the Elizabeth had reached 25 feet. Early in September the visitor started out to report to his employees, either Henry Champlin of Chicago or his uncle. [44]

In July 1907 Hubbard and Elliott were still boasting of their mines. Readers of the Alaska Monthly Magazine learned that they owned "the greatest and richest copper properties to be found anywhere in the world." It would be impossible to exaggerate the "size and richness" of their claims, according to a magazine writer, who believed that "the real truth is stronger than any fiction of the ordinary mining country." The new company, at an expense of $50,000, was completing a plant, "and will undoubtedly be shipping ore within a few weeks." [45]

All the hype between 1902 and 1907 was a little strange—whether truth or fiction. The partners did all right in selling stock but never did ship any ore—nor did anyone else. Stock sales provided support for other mining ventures carried on by the vigorous Hubbard for the next 60 years, but otherwise the Elliott-Hubbard Company affairs were only interesting because of litigation they inspired. Elliott's wife sued for divorce in 1907 and demanded a large share of the mine properties because of a grub-staking agreement. Judge James Wickersham determined that she had not been her husband's backer on the later expeditions that resulted in allegedly valuable claims. The Hubbards went to court in 1916, subsequent to a divorce, over his reneging on a mining property deed he had given her in 1906. The court refused to give the property back to him. [46]

The history of the Elliott Creek claims is richer in incident than other copper prospects in the region, but the bottom line was the same. It was far easier to announce "another jumbo" than to find one.

Kennecott: "Octopus" or Benefactor?

In Alaska the syndicate, often called "the Guggs," was either lauded for its development of resources or condemned for monopolistic practices and political corruption. James Wickersham, a friend to Birch and Jarvis until becoming congressional delegate in 1908, described the syndicate's "attempt to control the great national resources of Alaska in 1910 [which] destroyed the last Republican administration, split the Republican party into two factions, which destroyed each other in 1912, and gave the country eight years of President Wilson and his policies." Wickersham was referring to the celebrated Ballinger-Pinchot controversy involving charges of fraud in the syndicate's interest in acquiring coal claims in Alaska and the subsequent withdrawal of coal lands to entry. [47]

The Ballinger-Pinchot dispute loomed large as an issue affecting mining in the early years of the century. It was in essence a controversy over resource development and occasioned the nation's first, widespread public debate over conservation.

In 1904, Congress permitted entry to Alaska coal lands under private survey (because public surveys were lacking) but restricted individual holdings to 160 acres. When Clarence Cunningham made a number of locations, there were allegations that the Morgan-Guggenheim syndicate was involved in a scheme to control all the territory's coal. President Theodore Roosevelt responded by withdrawing all coal lands from entry by executive order.

Gifford Pinchot, chief of the U.S. Forest Service, pitted himself against Secretary of the Interior Richard Ballinger on the conservation issue. Ballinger, appointed secretary by President William H. Taft in 1909, had been commissioner of the General Land Office when an interior department investigator exposed an apparent Cunningham-syndicate relationship. Commissioner Ballinger ignored the allegations pressed in 1909-1910 by Pinchot, an ardent conservationist. Taft fired Pinchot for suggesting that he was in cahoots with Ballinger in the syndicate's plot to control public lands. Eventually, Congress investigated the affair and exonerated Ballinger. Pinchot did not give up the battle. Roosevelt took up his cause as a campaign issue when he ran as a third-party candidate in 1912 against Taft and Woodrow Wilson.

All the heat of the national controversy focused attention on Alaska mining and development and on the territory's aspirations for home rule. Alaskans believed that having effective representations in Congress and their own elected legislature would smooth the way to economic development. Alaska got its congressional delegate in 1906, and Wickersham successfully opposed Taft's plan for a military commissioner rule in 1909-1910. In 1914 the coal lands were opened for entry, but the expectations for their value had faded. Between 1906 and 1914, the Panama Canal opened to create lower coal freight rates from the East to the West Coast. Another significant event of these years was the commencement of petroleum production in California. [48]

In the furor directed towards the syndicate during the controversy, Dan Guggenheim was dismayed by the bitterness of his opponents. He believed that other men who had helped develop the frontier had been knighted while, in contrast, his enemies cried out for an indictment. Some Alaskans agreed that the syndicate deserved credit rather than censure. C.L. Andrews, formerly a long-time customs officer at Sitka, Skagway, and Eagle, praised the company in the Alaska-Yukon Magazine:

The men who are furnishing the capital for this road certainly have faith in Alaska. The United States bought the country for $7,200,000 and revolted at the price. She has put nothing into it since, beyond the revenue she has taken out; made no improvements of any moment worth mentioning; she has experimented in anomalous laws, and has prevented settlement of the accessible parts by withdrawing the coast in reservations; she has not even surveyed the land so a settler can get a farm without paying more for a survey than a pre-emption cost twenty years ago in the Western states. Yet here are men putting more than twice as much into developing the country as the United States paid for the whole,—for this road is estimated to cost $15,000,000 by the time it is completed. [49]

Andrews' views, expressed in 1910, were echoed decades later by Archie W. Shiels, who had been a storekeeper for Michael Heney during railroad construction. He quoted a speech made by Simon Guggenheim in 1910, directed against conservationists who argued that Alaska's riches belonged to the people. Guggenheim noted that the wealth was useless until found and developed: "men and capital must do the work, and it is risky for both. Both . . . are entitled to rewards commensurate with the risk, and if Alaska is to be developed at all, the interests of those two classes must be guarded as jealously as the interest of those who sit in comfort at home."

Sheil's argument followed the same vein:

When Kennecott was worked out and they quit Alaska, they were accused of taking untold millions out of the country and in return leaving nothing but a hole in the ground. No credit was given them for the millions they had put into the country in the way of taxes, wages, purchase of supplies, not to mention the purchase and operation of the Alaska Steamship Company, and just let me say that Alaska never did have a better or more satisfactory marine service than that given them while the Alaska Steamship Company was being operated by the Syndicate, all the political critics to the contrary . . . they spent over fifty million dollars in Alaska—not such a bad hole in the ground at that." [50]

Writing in the Engineering and Mining Journal, L.W. Storm ridiculed the assertions of the syndicate's enemies that the company had monopolistic tendencies. He argued that the Guggenheims owned only a single group of mines in a vast district and other powerful capitalistic interests including those of Anaconda, Calumet, and Hecla and James Phillips, Jr. of Nevada Consolidated were in the field before the Guggenheims. "The idea that there is any effort on the part of the Morgan-Guggenheim syndicate to control this extensive copper belt, save inasmuch as their railway is the first to penetrate it, is the subject of mirth in every prospector's cabin and in every operator's camp throughout this vast district." [51]

What miners and other Alaskans believed was not so easily summarized as Storm indicated. If numbers of them had not believed some of Wickersham's charges, it is unlikely that he would have won the biannual delegate elections from 1908-1914 when the controversy raged furiously.

The death of Dan Guggenheim in the Titanic disaster of 1912 had a great impact on the corporation's role in Alaska. Expansionist policies were curtailed, although the retrenchment did not change the prevailing unfavorable image of the "Guggs" among Alaskans.

The syndicate might have fared better in public regard but for its obvious determination to dominate Alaska politics. Copper River and Northwestern Railway workers, many of whom were not eligible to vote, were encouraged to vote against Wickersham at Cordova in the 1908 election for congressional delegate. This upset Wickersham who had already been annoyed by the syndicate's publication of earlier correspondence showing his interest in being retained as company counsel by the Guggs. Another exposure of letters by company officers revealed that Wickersham had not favored home rule for Alaska earlier, although he had made demands for a territorial legislature and other home-rule measures the thrust of his campaign.

After Wickersham gained office conflict with the syndicate went on, particularly over the control of political patronage. Wickersham determined to destroy the influence of the syndicate by any means at his disposal. By the time Stephen Birch got around to asking Wickersham to name his price for dropping his unrelenting attacks on the syndicate, it was far too late. Wickersham had become the champion of the people against the powers of evil—and the evil was represented by the syndicate and its supporters. But for their blunders and corruption, the syndicate might have fared much better during the storm of the Ballinger-Pinchot controversy and their support of President Taft's plan for a military government for Alaska in preference for more democratic institutions would have been less suspicious. [52]

Wickersham gained the ammunition he needed when H.J. Douglas, (not to be confused with Kennecott Superintendent William Douglass) recently fired as syndicate auditor, gave him evidence of Morrisey's role during the first Hasey trial. Douglas identified John Carson as the "bag man" who saw to it that Morrisey got money from the company's "corruption fund." A Carson letter to syndicate director David Jarvis extolled the services of Morrisey whose "acquaintances with many of the government's witnesses and control over them placed him in a position to be of the greatest service." Carson's letter was suggestive of jury tampering. Records of the actual disbursements to Morrisey were not extensive enough to be convincing of bribery but, as Wickersham pointed out, Douglas did not have all the evidence that might exist. [53]

Wickersham knew how to engage the attention of the press to the possible chicanery of the Guggs. And the syndicate men blundered further into providing him with a congressional forum for inquiry when they brought charges against U.S. Attorney John Boyce and U.S. Marshal Dan Sutherland. Boyce and Sutherland were dismissed because of alleged excessiveness in prosecuting Juneau banker C.M. Summers for assault. Summers and his good friend, Governor Walter Clark, were warm friends of the syndicate. Clark convinced the attorney general that Boyce and Sutherland prosecuted Summers merely because he was a foe of Wickersham. Whatever the truth, the dispute over the firings and replacement of the officers with John Rustgard and Herbert Faulkner was aired when a Senate subcommittee met to consider the fitness of the new appointees. Wickersham and Sutherland argued that the dismissals followed the efforts of the officers to investigate Hasey jury bribery charges. It is not clear that this was the case, but Wickersham did not neglect opportunities granted him to strike at his old enemies. [54]

The new officers were confirmed despite Wickersham's best efforts, but the attorney general could not resist Wickersham's demands for a thorough investigation of the Keystone Canyon trials, the election frauds at Cordova, and other questionable actions by the syndicate. Agents of the Justice Department went over the court records, interviewed a number of individuals, investigated the activities of suspects, and examined all the 1907-1908 telegraph communications of syndicate officers. Examiner S. McNamara reported the results of the investigation in February 1911. He concluded that "Morrisey is pre-eminently a scoundrel" and that "irregular methods" had been used by the Hasey defense. U.S. Attorney Elmer E. Todd of Seattle reviewed McNamara's report and agreed with his conclusions. "Improper methods" had been used by the defense, but the government did not have enough evidence to support a successful prosecution. [55]

It was the chicanery involved in a coal contract that eventually resulted in the prosecution of some syndicate officers. H.J. Douglas reported that the syndicate's David Jarvis had agreed with officers of another company on the price for coal to be offered for shipment to Forts Davis and Liscum in Alaska. Further investigation and much urging from Wickersham led to a federal prosecution of company officers at Tacoma, Washington.

The involvement of David Jarvis in corrupt practices of the syndicate was painful to many of his friends in Alaska and elsewhere. Jarvis had been admired by President Theodore Roosevelt, who considered him the embodiment of manly virtues—courage, decisiveness, intelligence, and integrity. Jarvis established himself as a national hero in 1898 when, as an officer in the U.S. Revenue Marine, he directed an overland reindeer expedition in relief of whalers caught in the arctic ice. Later, as Alaska's collector of customs, Jarvis enhanced his reputation. Roosevelt offered his favorite Alaskan the position of territorial governor in 1906 and, when Jarvis declined, accepted his recommendation of Wilford B. Hoggatt. Jarvis chose a more lucrative job as a director for the Alaska syndicate.

Jarvis was not among those convicted in October 1912 because he had taken his own life in June 1911, shortly after indictments were issued. Jarvis, who has been treated with great sympathy by historians of the event, left a cryptic note: "Tired and worn out." The New York Times story on his suicide observed his boldness "beyond the realization of people who did not know Alaska—whether lobbying for legislation, seizing railroad right-of-ways by power of Winchester, fixing jurors, or playing corrupt politics." [56]

A realistic assessment of the syndicate required the historian to weed out some of the stronger statements made by Wickersham and some glowing tributes recorded by syndicate fans. Some syndicate supporters like Margaret Harrais of Fairbanks were inclined to blame the government for policies that restricted the company's benefits to Alaska, including the failure to extend the Copper River and Northwest Railway from Chitina to Fairbanks. Harrais believed that "poison gas artists" had given financier J.P. Morgan a bad name: "He was featured as an octopus who was fastening his tentacles on Alaska's resources to suck the life-blood out of us." Harrais believed in the Morgan quoted at her dinner table by her guest Stephen Birch while the Copper River and Northwest Railway surveys were under way. "Steve," said Morgan to Birch,

when you go into that Tanana country, I want you to pay particular attention to the agricultural possibilities. . . . If those pioneers want to stay there after the gold is mined out, I'll build a railroad in there for them. I don't care a damn what it costs me, or whether I get a cent of the investment back! I'd like to make it possible for them to remain. John D. Rockefeller has built churches and Andrew Carnegie libraries, as their monuments—I am going to build a railroad to benefit those Alaska pioneers as my monument. [57]

This story made Harrais "gasp for a moment," but she believed it. Morgan did not fulfill his promise but, she believed, it was because the conservationists led by Gilbert Pinchot excoriated everyone who wished to develop Alaska and their nastiness dissuaded Morgan. Yet Morgan did make it possible for Birch to develop the copper mines, "give employment to thousands of men at good wages, give the prospector a chance to earn a grubstake and keep him in Alaska, and enriched the world by over $200,000,000 in new wealth."

The syndicate chose to invest its Kennecott profits elsewhere, Harrais believed, because of the ugly treatment received in Alaska. [58] Morgan's death in 1913, like that of Dan Guggenheim a year earlier, affected the corporation's expansionist policies in Alaska. It is also possible that the widespread unfavorable publicity over the Keystone Canyon shootout diminished enthusiasm for pushing the railroad into the interior. Historians have been divided in evaluating the syndicate. Jeanette P. Nichols believed that the syndicate exploited Alaska through its control of shipping and political corruption. Robert Stearn and Lone Janson are much more favorable to the syndicate. [59] Melody Webb's summary offers a balanced view:

The syndicate touched every facet of life—political and economic, national, and local. In part, Alaska's small population invited this impact. The company's steamships carried nearly all supplies and passengers between Alaska and Seattle. Its railroad was the longest and best constructed in the territory, with equitable rates while operating at a loss each year. Its fisheries, canneries, and merchandise outlets supplied needs to a developing territory. Its copper production stimulated other mineral development. And its large capital investment brought economic opportunity to an isolated area. Most important, the syndicate was the parent from which the giant Kennecott Copper Corporation grew, providing the foundation for the more adaptable corporation. The syndicate, however, did involve itself in a brand of both national and local politics that at best must be judged as 'misconduct.' Overall, its role in Alaskan affairs seems more positive than negative. [60]

Notes: Chapter 13

1. Copper River Mining Co. v. McClellan, 2 Alaska Reports, 134. The case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Published depositions of all parties involved including Major W.R. Abercrombie are part of the file for case #20006 which is in the National Archives.

2. William C. Douglass, "A History of the Kennecott Mines," typescript, NPS files, 4.

3. E.J.E. Schuster, "The Reynolds System," (Anchorage Daily News, "Alaska Living," July 30, 1967, 7-9), passim.

4. Hazelet to Hasey, September 2, 1907, Keystone Canyon Collection, microfilm 140, UAF.

5. Perry to Lathrop, September 16, 1907; Lathrop to Perry, September 19, 1907, Keystone Canyon Collection, microfilm 140, UAF.

6. McAdams to Chief Wilkie, March 18, 1908, Keystone Canyon Collection, microfilm 140, UAF.

7. Hoggatt to Secretary of Interior, October 26, 1907, Keystone Canyon Collection, microfilm 140, UAF. Wickersham diary, March 27, March 28, April 1, 1908, AHL. Wickersham attributed Harlan's behavior to grief caused by his son's death.

8. Roosevelt to attorney general, December 27, 1907, February 10, 1908, Bonaparte Papers, Library of Congress.

9. McAdams to Chief Wilkie, March 20, 1908, Keystone Canyon Collection, microfilm 140, UAF.

10. Ostrander to Tom Donohoe, March 28, 1908, Donohoe-Ostrander Collection, UAF.

11. Ostrander to Tom Donohoe, April 12, 1908, Ostrander-Donohoe Collection, UAF; the district court record is U.S. v. Hasey, case 545B, RG21, FRC.

12. Woodrow Johansen, "The Copper River and Northwestern Railroad," Northern Engineer, Vol. 7, No. 2, Summer 1975), 19-31.

13. Carlyle Ellis, "The Winter's Crucial Battle on Copper River," (Alaska-Yukon Magazine, June 1910), 27-35; Sidney D. Charles, "The Conquering of the Copper," (Alaska-Yukon Magazine, December, 1910), 365-70; Hawkins' report. Copy in NPS files.

14. Woodrow Johansen, "The Copper River & Northwestern Railroad," (Northern Engineer, Vol. 7, No. 2, Summer 1975), 25.

15. John Kinney, "Copper and the Settlement of South-Central Alaska," (Journal of the West, May Vol. 10, No. 2, April 1971), 311.

16. May Grinnell, "Cordova," (Alaska-Yukon Magazine, August 1909), 327.

17. W.K. Keller to Julia Seltenrich, December 15, 1931, McKay collection, UAF.

18. The 49th Star, September 21, 1946.

19. W.E. Dunkle, "Economic Geology and History of the Copper River District," (paper at Alaska Engineers Meeting, Juneau, 1954), 3-5. Mackay Collection, UAF.

20. Douglass, "A History of the Kennecott Mines," 6-7.

21. Alfred H. Brooks, Mineral Resources of Alaska: Report on Progress of Investigation in 1919, USGS Bulletin No. 714 (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1921), 194-96.

22. John Kinney, "Copper and the Settlement of South-Central Alaska," (Journal of the West, Vol. 10, No 2, April 1971), 315.

23. Melody Grauman Webb, "Big Business in Alaska: The Kennecott Mines, 1898-1938," (Fairbanks: Cooperative Parks Studies Unit, 1977), 37.

24. Robert L. Spude and Sandra M. Faulkner, "Kennecott, Alaska," (Anchorage: NPS, 1987), 7.

25. Grauman Webb, "Big Business in Alaska," 38.

26. "General Points of Interest on the Kennecott Mother Lode Mines," July 15, 1924. Kennecott Collection, UAF.

27. Contract of June 7, 1923. McCracken Collection, UAF.