|

Parks, Politics, and the People

|

|

|

Chapter 5: The Civilian Conservation Corps Once the first camp was established and operating in Virginia, President Roosevelt wanted to visit it to see how things were getting along. He traveled from Washington to Harrisonburg, Virginia, by train. At Harrisonburg a large crowd was on hand to greet and cheer him. The Roosevelt image—the smile and the cigarette in its holder—was very much in evidence. From there he went up to George Washington National Forest in the Massanutten Mountain Range, where the first CCC camp had been established and named Camp Roosevelt in his honor. He spent some time there and then went over to Shenandoah National Park at Big Meadows, where the first Park Service camp, Camp Fechner, was in operation. He got there in time for lunch and chatted with the boys. One of the newspaper photographers took a picture of the president having lunch, with the boys standing several rows deep on three sides of the table (see p. 104). Fred Morrell, of the Forest Service (my counterpart in the Department of Agriculture), and I got copies and had all of the dignitaries, with the exception of the president, autograph them. We then asked Mike Reilly, of the White House secret service detail, if he could get the president to autograph our pictures. Mike took the two pictures to the White House and for some time we heard nothing from him. Finally he replied, saying that the president would not autograph them until we got a duplicate copy for him with all the signatures on it. Of course, we dug out another picture, got it autographed, and sent it to the president, and then we got our copies back with the president's signature. His copy is now in his library at Hyde Park, New York. I gave my copy to Superintendent Taylor Hoskins of Shenandoah National Park to put in the Harry F. Byrd Visitor Center, which looks out over Big Meadows and is not far from the CCC camp where the picture was taken.

The four districts set up to handle state park work began operations on May 15. By that time the states had received camp application forms, and some state areas had been cleared for establishing camps. Of course, the better-organized National Park Service had no real trouble putting 70 camps into full operation by June 30. The last half of the first six-month period, from July 1 to September 30, was a time for settling down and getting ready for the second CCC period, which was to begin October 1. The state parks used this time to organize and prepare acceptable applications, looking toward an increase in the number of camps at the beginning of the second period. The camp allotments for that period afforded a better balance between the Departments of Agriculture and the Interior, giving agriculture 993, interior 440, and the other agencies and the military, 35. This brought national park camps up from 70 to 102, and state park camps from 102 to 263. Allotments to the other bureaus of the department remained approximately the same as in the first period. The reasons for selecting six-month periods was never explained, but perhaps it was related to the fact that the CCC was never considered a permanent program and depended on emergency and temporary legislation for its existence. Furthermore, it was felt that the CCC was a stopgap employment opportunity and that a period of six months would be long enough for some enrollees, who could then find regular work in their home communities. No enrollee was permitted to serve more than four terms, or two years, and very few stayed that long. Some of them did so well, however, that they were taken on as foremen or LEMs by the supervising technical agencies. Although the six-month periods applied also to the appointed supervisory personnel, there was no limit on reappointment. The requirement of operating by periods necessitated the submission of proposed work programs every six months and the moving of camps to accommodate work programs. After the first period all programs had to be submitted at least two months in advance of the beginning of a period, which meant that the departments had to get together and determine how many camps each department would have for its bureaus. When that was decided it was necessary within the department to settle on the allotment of camps among the bureaus. It was not always possible for the Departments of the Interior and Agriculture to agree on camp allocations, but they both objected to putting camps on military reservations. The Interior Department felt that the Agriculture Department, on the first go-around, actually took more camps than they deserved, although the Department of Agriculture did already have basic legislation to cooperate with the states and also had authority to cooperate with the owners of timberland. In the periods that followed, beginning with the second period on October 1, 1933, adjustments between the two departments—interior and agriculture—were worked out to the satisfaction of both. The table on page 107 shows distribution of the work camps among the bureaus and the personnel directly connected with them as of the end of September, 1933. The last three columns of the table will give the reader an idea of the size of the camps and of the number of supervisory personnel in the camps at the end of the first six-month period. The military camps are separated from the rest in order to give a more accurate picture, since the military camps served as stopover points for enrollees on their way to other camps. Some 2,000 of the 3,554 enrollees included in the chart under military camps were actually being cleared for transportation to other work camps. The CCC program was gradually being accepted by the entire country. At first some communities didn't want CCC "vagrants" in their neighborhoods. That is a harsh way to put it, but many people at first thought that these boys were being picked up off the streets and put in the camps as a sort of punitive relief measure, equated with the handling of delinquents. But this idea was unfounded. The boys did a wonderful job; they were on the whole good, clean, hard-working, and friendly young men, who became a part of the communities in which their camps were located. When the workday was over and they had time off to go into town, they changed into neat, good-looking dress uniforms that they were proud to wear. The CCC as an organization earned a fine reputation, and, with due respect to all of us behind the lines, the boys themselves deserve a large part of the credit for its success. The program's success showed me that there is nothing wrong with the younger generation in a country like ours, where they have the opportunity to prove themselves. Everybody knows that not every individual can be a top person or leader but that each one can be respected for contributing his best to his community. A Breakdown of the Work Camps

I have often wondered what a big-city boy's reaction was to the CCC camp environment and what long-range effect the experience had on the boys. In my files I find an article written by a man who went all the way from New York City to a Forest Service camp in Idaho ten miles from the nearest town. It was a big change for him. He tells of a certain amount of razzing he got from the camp old-timers when he arrived. But then he goes on and tells how, after some of the boys left when their six months were up and new boys came in by train, he took part as an old-timer in razzing them. He especially notes that the scenery was absolutely gorgeous. Part of his time was spent in building a road. Later he was made an aide to an engineer staking out a new road location. He apparently finished his six-month tour toward the end of March, having spent the winter in the cold but beautiful mountains of Idaho. He concludes with the following paragraph:

This paragraph is taken from "The CCC, Six Months in Garden Valley," by Donald Tanasoca, edited by Elmo Richardson, published in the summer of 1967 in the magazine Idaho Yesterdays. Long after the CCC was closed out, many groups of enrollees and supervisory personnel got together to talk over the CCC days. One such gathering took place at Fort Pulaski National Monument, Georgia. National Park Service Superintendent Ralston B. Lattimore had taken great interest in the boys, most of whom were from the Atlanta area. After their CCC and World War II military service, they had settled down as businessmen, bankers, insurance men, and so forth. Several of them got in touch with Superintendent Lattimore to arrange a reunion back at Pulaski. They had several reunions over the years. In his report on the reunion of 1950, Superintendent Lattimore described what had happened to some of the men who had been in the CCC ten to fifteen years earlier.

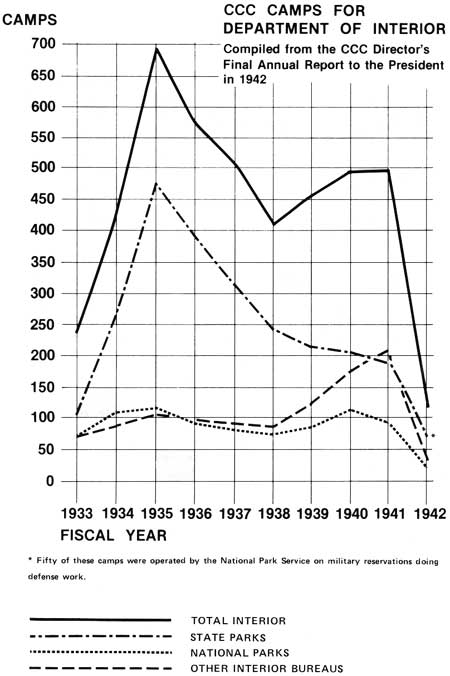

The national and state park CCC organization outgrew the Interior Department's CCC office in Washington and needed additional space. During the second period, in the fall of 1933, offices were leased in the Bond Building at Fourteenth Street and New York Avenue, N. W. The department activities stayed in the Interior Building as did the Park Service's Branch of Lands. As assistant director in charge of the Branch of Lands, now called the Branch of Lands and State Cooperation, I divided my time between the two buildings, putting Herb Evison in charge of the activities in the Bond Building when I was not there. The arrangement we had with the states was the simplest and most satisfactory we could devise. It was actually an extension of the understandings that were developed in 1921 when the National Conference on State Parks was organized. There was no sign of any sort in that organization that indicated a desire on the part of the federal park people to take over the states' responsibilities or even to tell them what to do. Both federal and state people realized there was a lot to be gained by the exchange of ideas. So when the CCC was started it was only natural to assume that we should continue this mutually advantageous relationship. While the army finance officer paid the bills, we asked the state authorities to act as our procurement agents. The CCC camps were turned over to them, and, although the camp superintendents and the technical men who supervised the work were paid out of federal funds, they reported directly to the state park authorities. Each period we would divide our money among all the camps on an even basis. The state park authorities knew how much money they had for each camp. I'm sure there were some camps that over-expended, but there was enough savings at other camps within a park authority so that overall each state stayed within the total amount allotted. In fact, after the second year we found that 5 per cent of our funds were unexpended at the end of the fiscal year, while certain very important jobs were actually being held up because of lack of funds. So the next year, on the advice of our fiscal office, I allotted 5 per cent more money than we actually had for allotment. At the end of that fiscal year we still had a big reserve, and important projects delayed, so the next year I allotted 10 per cent more. That time we came out with a relatively small reserve at the end of the fiscal year—about 1-1/2 per cent. As explained earlier, the four district offices for the state, county, and metropolitan parks CCC program were established on May 15, 1933. Their main purpose was to process applications and give careful review and general supervision to planning and carrying out the work. The state park offices prepared project plans and took care of employment and procurement. We reasoned that the district offices, later designated regional offices, should be limited in size to be closer to the work. Therefore, as the state, county, and metropolitan camps increased in number, we established additional regions so that each would be assigned about fifty camps. There were as many as eight regions at the height of the program, and as few as four. The chart on page 112 indicates, by years, the variation in the number of camps assigned to the Interior Department.

The camp inspectors we hired to supplement our regular staff were professional landscape architects, engineers, or foresters with considerable experience. Although many of them had very little direct experience in park and recreation planning, development, and management, it did not take them long to adjust to park and recreation principles and requirements. Nevertheless, it became necessary early in the state park program to call their attention to certain reports from several permanent Park Service field people, and from some inspectors, that the planning and development operation was not up to standard in the state parks. We were prompted to write a long letter to the regional officers and inspectors, and it proved very effective. They gave copies to the state authorities, who were eager to avoid losing any camps. In the letter we stated that the park authorities in the states either hadn't understood or had failed to accept the fundamental principles of good land use planning and the problems of park development and sound management. Consequently large portions of the parks were being modified by unnecessary man-made intrusions that were costly and would needlessly increase maintenance and administrative costs in the future. We tried to point out that scattered, intensive uses meant increased costs in developing and maintaining roads, in water distribution, and in waste disposal. Such use would also increase fire hazards. We explained that the three basic essentials of a people's park are easy access, safe and abundant water supply, and adequate sanitary facilities. We clearly implied that if these essentials were not fully provided we would have to reassign the CCC camps. We also pointed out that many of the plans submitted for overnight accommodations looked like summer homes, whereas we were interested only in inexpensive accommodations, especially campgrounds. We discouraged construction of roads other than those that would provide access to points of intensive use, and we insisted that entrance roads be limited to the lowest possible number. We required that structures of long durability, such as those constructed of stone or masonry, be justified on a long-term basis and that all structures be designed to blend with the landscape. Further, we suggested that with a little thought the entrances to parks could be made unobtrusive and inviting rather than massive and forbidding. Although we did not say it in so many words, we strongly implied that these were the principles that would govern all future camp allotments, and the implication proved strong enough to improve all future applications for camps and to effect changes, where necessary, in the work programs of existing camps. Twice a year we would call the procurement officers and regional directors into the Washington office for a week's seminar to discuss progress, new concepts, problems, and everything imaginable. Since our procurement officers were the state authorities, there were a lot of things we had to talk over besides the CCC—our recreational demonstration projects, state laws, nationwide studies, park management programs, methods of raising funds for land acquisition, to name a few. These discussions of major concepts looked toward the long-range evolvement of a nationwide system of parks for the American people. At the request of various states, the National Park Service counseled them on drafting legislation to provide the necessary legal authority to plan, develop, and maintain state park systems. One state went so far as to include in its legislation a provision that the director of state parks be appointed by the governor subject to the approval of the director of the National Park Service. When the National Park Service learned of this, we immediately asked that the law be amended to rescind that provision and that the qualifications for the position be set forth in its place. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

|

| ||

Parks, Politics, and the People ©1980, University of Oklahama Press wirth2/chap5b.htm — 21-Sep-2004 Copyright © 1980 University of Oklahoma Press, returned to the author in 1984. Offset rights University of Oklahoma Press. Material from this edition may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the heir(s) of the Conrad L. Wirth estate and the University of Oklahoma Press. | ||