|

Parks, Politics, and the People

|

|

|

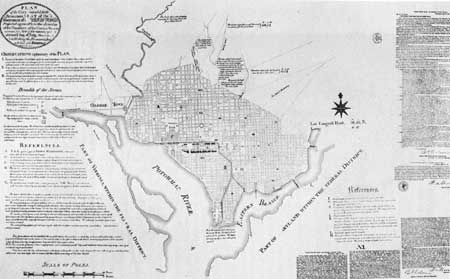

Chapter 2: Introduction to Washington: The National Capital Park and Planning Commission At the age of twenty-eight I placed my young wife and our ten-month-old boy with our parents in Minneapolis and Saint Paul and went to Washington to begin a career in the federal government. I had to leave my little family behind until I could afford to bring them east. I had been out of work for over nine months, we were broke, and our debts were staggering. It was a rather warm but windy Tuesday in May, 1928, when I arrived in Washington on an early train. After checking the newspapers to see about a room, I decided to delay renting one until I had called at the National Capital Park and Planning Commission, since perhaps there I could get advice as to a suitable location. The offices were then in the World War I temporary Navy Building at Constitution Avenue and Eighteenth Street, N.W. Because I had more time than money, I checked my bag for ten cents in Union Station, walked the eighteen blocks to the Navy Building, and got there a half-hour before the offices were to open at 8:00. I waited around a few minutes before Mrs. Nettie Benson arrived. Mrs. Benson was later to become secretary to two National Park Service directors and, in 1951, my administrative assistant. At that time she was secretary to Lieutenant Colonel U. S. Grant III, who then had three titles: vice-chairman and executive and disbursing officer of the National Capital Park and Planning Commission and engineer in charge of the Office of Public Buildings and Grounds of the National Capital. The latter agency built, operated, and maintained the federal parks and buildings in the city of Washington and the nearby region. Grant was one of the finest Corps of Engineers officers I have ever known, a man who was not only an excellent engineer but a fine administrative officer, a gentleman, and a strong conservationist of our natural environment, deeply involved in the preservation of our historic heritage. I was very fortunate to have the opportunity of working under his direction. I had first met Colonel Grant some five weeks before, early in April. But I had not yet met the staffs of the planning commission and the Office of Public Buildings and Grounds. After a short talk Grant took me down to meet the staff of the planning commission, including Major Carey H. Brown, assistant executive officer to Grant, and Charles W. Eliot II, director of planning. I was to join Eliot's staff in the planning commission, but I soon learned that the colonel had assignments for me in connection with the operation of the parks of Washington as well. Therefore I was taken to meet Major Joseph C. Mchaffey, Grant's assistant in the Office of Public Buildings and Grounds. He in turn took me to meet the top-flight park people charged with responsibilities for the parks of Washington. I met Captain Kelly, chief of the park police; Frank Gartside, general manager of the parks; George Clark, the chief engineer; and John Nagel, who was the engineer responsible for such big construction projects as the Arlington Memorial Bridge. I also met Charles Peters, who was then in charge of the federal buildings and who through the years became a very dear friend. By his reorganization order (no. 6166) of June 10, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt transferred to the National Park Service the entire Office of Public Buildings and Grounds. So, the group of fine park people I met that morning in May, 1928, became National Park Service people. After meeting my new colleagues, being assigned a drafting board and part of a desk, and having lunch in a cafeteria on the roof of the old Navy Building, I inquired about where I might look for a room on a weekly or monthly basis. I was told that there were fairly good and reasonable places in northwest Washington. I spent that afternoon looking for a room and found one that suited my strained financial situation, though the landlord required a down payment of one week's rent. That night I quickly discovered the bed was infested with bedbugs, and the next morning I packed my bags and left, reluctantly forfeiting my first week's rent. It occurred to me that there were a couple of universities in Washington and that possibly one of them had a chapter of the Kappa Sigma fraternity, of which I was a member. Sure enough, there was a chapter at George Washington University, and they had a room for me. Apparently they needed a few paying guests, even though the state of my funds required that they wait until my first payday for the rent money. On May 17, I received my appointment. The National Capital Park and Planning Commission was established by Congress in 1926, made up of several odd committees established in earlier years for special projects with no effective coordination to develop a sound comprehensive plan for the National Capital. Shortly after the federal government was established on April 30, 1789, and Congress started meeting, it was realized that it would be very difficult for the government to operate in any of the existing cities. President George Washington was authorized to proceed with the selection of a seat of government and the plans to develop the national capital. He employed Major Pierre Charles L'Enfant, of France, for the task. L'Enfant, working with the president and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, laid out a plan for the city of Washington and the District of Columbia. Construction was started shortly after 1791, and in 1800 Congress moved to Washington.

While the plan prepared for the city of Washington in the late eighteenth century was a very good one, very advanced in relation to those of other cities in the United States at that time, a lack of continuous attention caused it to deteriorate during the nineteenth century. Alterations in the plan were made at times during the nineteenth century to satisfy political and personal interests. These changes more often than not were at odds with original concepts of Washington as the capital city of a great nation. Consequently, in late 1898, when the first hundred years had passed and an anniversary celebration was being planned, the central part of the city, especially the Mall area, was in sorry condition. Permits had been granted for buildings in the Mall, cattle and other livestock were grazed there, and Congress had approved the building of the railroad station at the foot of Capitol Hill. The people of the District of Columbia worked hard making arrangements for the centennial, which naturally took on a national aspect. A joint committee of the two houses of Congress was appointed to act with the citizens' committee in planning the celebration. The celebration was very successful and was brought to a very satisfactory conclusion with a reception and ban quet given by the Washington Board of Trade in honor of the congressional committee and distinguished guests. However, a good deal of dissatisfaction was expressed by people throughout the country with the conditions they found in Washington. As a result Senator James McMillen, chairman of the Committee on the District of Columbia, introduced a resolution which, when passed on March 8, 1901, instructed his committee as follows:

Senator McMillen and his committee selected Daniel H. Burham, a noted architect from Chicago, and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., a nationally recognized planner and landscape architect of Brookline, Massachusetts, and gave these two gentlemen the opportunity to add to their committee for the study as they saw fit. Burnham and Olmsted chose as their colleagues Charles F. McKim, a well-known and capable architect of New York, and one of America's great sculptors, Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The report that resulted, often referred to as the McMillen Report, really stirred things up. On the front page of the second edition, dated March 14, 1903, a note by the Senate Committee on the District of Columbia states:

All these projects were recommended in the first edition of the McMillen Report. Within a little more than a year those actions had been taken. Thus did Congress eagerly begin carrying out the recommendations of the report and continued to do so in the first two decades of the century. An Act of Congress of May 17, 1910, established a permanent Commission of Fine Arts. A zoning law passed in 1920 provided the authority to control building set back and elevation of buildings in conformity with the overall city plan. In 1924, Congress made provisions for the detailed planning of a public park and open space system, recognizing the failure to carry out the proposals of the 1901 plan for an open space system so important to the growing population of the city. Very soon the National Capital Park Commission and Congress came to the conclusion that a satisfactory park system could not be laid down without the full knowledge of the inter-relationship of parks, roads, zoning, building, and other elements of a comprehensive city plan. The authority of the commission was therefore broadened in 1926, when it was given its new title and responsibilities as the National Capital Park and Planning Commission. The authority of the presently named National Capital Planning Commission has been extended to regional responsibility, insofar as federal interests are concerned, which requires close cooperation with the authorities of Maryland and Virginia surrounding Washington.

After I had settled into my work in Washington, I found that one of the big things the commission, other governing agencies, civic groups, and Congress were working on was a proposed piece of legislation called the Cramton-Capper Bill. The sponsors of the bill were Representative Louis C. Cramton, from Michigan, and Senator Arthur Capper, from Kansas. Representative Cramton, one of my heroes, was chairman of the House Subcommittee on Appropriations, which handled the Park Service's as well as the Planning Commission's appropriations. He had been associated with many of my other idols, such as Horace Albright, U. S. Grant III, J. Horace McFarland, Frederic Delano, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., and Miss Harlean James, secretary of the American Civic Association. Several of this group had worked for some ten years to establish the National Park Service and, joining with Mather and Albright, helped to get the legislation passed authorizing the service in 1916. This same group, along with others, were the backers of the establishment of the planning commission in 1926. Cramton was perhaps as much a Park Service man as he was a member of Congress. He befriended the service particularly when we greatly needed his help during the late twenties and early thirties. The Cramton-Capper Bill called for an appropriation of some thirty-two million dollars for land acquisition for parks and for stream-valley protection within and adjacent to the District of Columbia. It included establishment of the George Washington Memorial Parkway on both sides of the Potomac River from just above Great Falls, upriver from Washington, to Mount Vernon on the Virginia side and to Fort Washington on the Maryland side, downriver. It also included acquisition of land for the city's park and recreation system and the development of a Fort-to-Fort Drive connecting the Civil War forts that ringed the capital. The growth of the city was such that by the time acquisition funds were available it was no longer practicable to build the Fort-to-Fort Drive, although practically all of the fort sites had been acquired and are now part of the city park system. The bill included aid to the counties in Virginia and Maryland bordering the District of Columbia on a matching-fund basis for the development of their park systems. |

|

| ||

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

|

| ||

Parks, Politics, and the People ©1980, University of Oklahama Press wirth2/chap2.htm — 21-Sep-2004 Copyright © 1980 University of Oklahoma Press, returned to the author in 1984. Offset rights University of Oklahoma Press. Material from this edition may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the heir(s) of the Conrad L. Wirth estate and the University of Oklahoma Press. | ||