|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Conducted Trips |

|

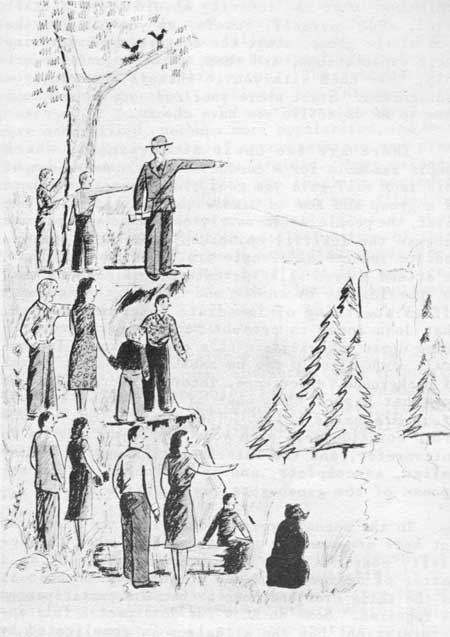

...A GOOD INTERPRETIVE JOB

CHAPTER IV

CONDUCTED TRIP INTERPRETATION

So far we have been concerned with the mechanics of managing a conducted trip. Now let us turn our attention to the equally important matter of handling the interpretive phase of this activity. The general principles of interpretation, some of which are outlined in the publication Talks, are applicable, but there are some special and unique factors involved too. The basic problem is that of developing and preserving the structure and unity of the interpretive story--of making it hang together as one story despite the fact that the telling is repeatedly interrupted by the movement of the party from place to place.

The backgrounds and attitudes of the audience enter into the problem. The subject matter itself is a factor. Good planning and complete preparation are essential in achieving this objective, and a great deal depends as well upon the manner of presentation and the techniques employed in telling the story. We shall, then, discuss audience, subject field, planning and preparation, and presentation methods as they contribute to effective conducted trip interpretation.

First, however, let us make two suggestions. Again read the publication on Talks. The general interpretive concepts, and especially the suggestions for planning an interpretive story, will be of value to you. Secondly, after you have conducted a few groups over a tour route, come back and again read this discussion of conducted trips. Your own experiences will give this discussion more meaning and you will be able to apply and adapt the material in this manual in new ways to the interpretive job at hand. A conducted trip is a thing of continuous development, and you may take a trip a dozen or more times before you begin to be satisfied with your performance. Insofar as you can profit by the experience of others, and this booklet contains the essence of the experiences of a great many interpreters before you, you can shorten that period of learning and development.

A Conducted Trip is for People

Like any other interpretive activity, a conducted trip should be adjusted in subject material and in method of presentation to the people it serves. You do not cast pearls before swine, and it is equally inappropriate to explain the ABC's to a PhD. Pattern the activity to fit both the backgrounds and the expectations of the group. Correct appraisal of background and experience enables you to couch the interpretation in words and concepts familiar to the listener, and to project ideas into situations familiar to him. It enables you to avoid the attitude of superiority that results in talking down to an audience.

It is just as important to ask "What does the visitor want and expect from this activity?" and to be very realistic in arriving at the answer. Your standard trip may be entirely inadequate for a visiting scientific or historical society, and completely beyond acceptance by a high school group out for a field day. This does not mean that your course is alone determined by the desires of your group. You have an objective and a purpose too. It does mean that the interest level and the expectations of the group should be recognized at the beginning, that the activity should start at that level. Put yourself, insofar as you can, in the mood of the group, start the activity by satisfying their expectations, and then, through your leadership, take them with you to whatever heights you can achieve. Start where your audience is and take them to an objective you have chosen.

There are two basic situations in which people assemble for a conducted trip. Awareness of this fact will give you good clues as to the nature of a group and how to handle the activity. In the first, the people deliberately choose to participate because the activity coincides with their own immediate interests. People are under no compulsion to attend a bird walk or nature walk. Those that do, participate by choice and because the activity offers something of immediate interest to them. That John Jones is present because Mary Brown is going doesn't invalidate this observation. In general, such a group can be assumed to have a level of background, experience, interest and expectation somewhat higher than that of the second type of group discussed below. The expectations of the group coincide well with your own objectives as an interpreter, and the interpretation may be as detailed, as complete, and as prolonged as the response of the group justifies.

In the second type of situation, the people do not know necessarily in advance just what the activity consists of. They participate, not as a matter of deliberation and choice, but because it is the thing everyone does or because participation is required. Some do know and do expect a full interpretation, but the situation is complicated by the presence of many others who have no well defined expectations. Some of them may merely want to cool off in a cavern, or to see the view from the top of a fortification. In such situations, the interpreter needs to use to the fullest degree his skills of presentation, and he must be especially sensitive to the reactions of his group. The interpretive story should be as attractively and interestingly presented as possible. In most cases it should be more generalized, perhaps more popularized, and less detailed. Heavy doses of interpretation and prolonged discussion are to be avoided. Long windedness simply means that you are thinking too much about yourself and your subject, and have failed to consider the interests and expectations of your audience. Remember that in most situations of this kind the people have paid a special guide fee. They are entitled to the best possible service, taking into account both your objectives and their expectations.

In summary, appraise your audience, be alert to sense their reactions, and serve their interests as well as your own objectives. If you have a genuine interest in the people you serve, it will be immediately evident to them and will be reflected in a friendly attitude and in good rapport.

The Subject Field and Its Interpretive Characteristics

The National Park Service is concerned with two distinct subject fields--natural history and human history. Each field possesses certain characteristics which facilitate, and others which complicate the solution of an interpretive problem. Subject matter itself conditions the approach to interpretation.

For example, in historic areas the significant theme is so defined as to throw into sharp focus a single episode, person, period of time, or concept. Background, prelude, and postlude only sharpen that focus. The story is often presented in time sequence. Thus, it has inherent organization and unity, it develops logically, and achieves climax. The story hangs together because it is in fact one story. The leader of a tour, exercising ingenuity and imagination, will capitalize to the fullest degree on this favorable characteristic of the historical tour.

By contrast, most scenic-scientific areas deal with a much diversified subject field. Many aspects of many branches of natural science, and often history, may be involved in a single interpretive presentation. Unity and coherence are not innate qualities, but must be achieved by seeking out and utilizing broad concepts such as ecological relationships.

In most scenic-scientific areas, the immediate setting, the items that are at hand and visible, are the objects of primary interest--the canyon, the geyser, a stalactite, tree, or flower. In historic areas, the setting, and the physical objects are present too, but primary interests lie in events of the past. The past events are absent and must be recreated in the minds of the visitors. The battlefield of Gettysburg provides the setting, but the interpreter must help the visitor visualize the military action that occurred in the past. The prehistoric structures are present at Mesa Verde, but must be peopled and brought to life in the imagination of the visitor.

Similarly geological interpretations, based on a present day scene, often involve a whole series of separate and distinct events of the past. Thus, at Grand Canyon the interpreter presents a scene as it exists and is in view today. But to fully understand the scene, the visitor must be helped to visualize the action of forces which, during many distinct periods of the past, created that scene. Geological time sequence is a very difficult concept for most people to grasp. To simplify this concept, the Grand Canyon story often is presented as chapters in the book of time which lies open and exposed in the canyon walls. In other places, geologic time is reduced to a lifetime, a year, or a day--concepts that are scaled to human experience.

Historical and archeological subjects possess another favorable quality of which the skilled interpreter will take full advantage. The story is essentially about people and their activities. People are most interested in other people, and the interpretive story can be given the drama of human interest to a degree not usually possible in other situations.

These general observations merely illustrate that most subject fields do possess characteristics affecting the interpretive presentation. In approaching a new problem, ask yourself this question: What are the factors in this subject field, at this place, and at this time, which may be utilized to strengthen the interpretive plan?

A Conducted Trip is an Illustrated Talk

Like an illustrated talk, a conducted trip interpretation can be either a disjointed, unorganized catalogue of facts, or it may be a well rounded, unified story. Especially during the planning stages, it is very helpful to consider the similarities between these two activities. Like a talk, a conducted trip should have a plot or theme. It should set the stage and generate interest through a good introduction, it should develop logically and reach an effective conclusion. It may utilize supporting material, suspense, climax, rhetorical question, illustration and other techniques that make an illustrated talk effective. Good planning and complete preparation are fundamental, and the following suggestions toward this end will be found helpful:

Take an Inventory.--First, of course, is to explore the tour route. Familiarize yourself with the route, get an idea of timing, and discover just what the route offers as illustrative materials. Take an inventory, make a list of objects, features, sites, and views. Sometimes these are obvious and fit into a ready-made pattern as on a battlefield tour, a geyser walk, or other special subject tours. In others, a great variety of less obvious and apparently unrelated things compose your list.

Build up a Fund of Facts and Supplemental Information.--Next, find out all you can about the things on your list, not merely names and descriptions. Names, dates, classifications, and events in history are the basic facts. Supplement these with supporting data just as you enliven a talk with story, comparison, or other human interest material. You will never have too much data, and a full fund will enable you to vary the activity for your own greater interest, as well as to meet the varying demands of different audiences.

Define the Plot.--A conducted trip should have a theme or plot just as does a well-organized talk. How else but through a central theme can you achieve unity and logical development, and bring all to a meaningful conclusion? Without this you fall into the same rut as the unprepared speaker who introduces each new picture with the comment, "The next picture shows . ." A theme lifts the activity above the sphere of mere identification, makes it more exciting for you, and gives it more meaning for the visitor.

The significant theme of the area plus all the specific information you have assembled along the tour route will suggest the plot. Your own background and your resourcefulness and imagination come into full play too. Try to express this central idea in a single sentence or short paragraph.

On many trips the story line is self-evident--"How Petrified Wood is Formed," "Ancient Apartment Dwellers at Mesa Verde," "The Battle of Gettysburg." Even these can often be slanted or angled to make a better story. Gettysburg might be presented through the eyes of Meade or Lee. Make the petrified wood story an example of a problem in scientific method, seeking out clues, exploring their meanings, and finally developing an hypothesis. Don't talk about sticks and stones but populate a ruin or house with human beings. An interpretive presentation does not have to be couched always in the same form as a classroom lecture.

In other situations, a great deal of imagination is called for in devising a plot without creating a forced or artificial situation. For example: A tour route at Mammoth Hot Springs encounters dead formations, hot springs in various stages of activity, scenic views, geologic features, flowers in season, forests, and certain birds and animals. Mere identification and description of individual features constitute a hodge-podge, purposeless, and disunited presentation. On the other hand, the same observations can be woven into a theme such as "Nature is progressive and exhibits an orderly pattern of change." Each pertinent object is, of course, identified, described, and explained, but in addition, it is given relationship to the entire scene. The basic theme ties the whole together, and gives it purpose and meaning. Long after the participants have forgotten the name of the flower, the name of a formation, or the temperature of the hot spring, they will remember and will be stimulated to look for other evidences of order and change in nature.

Make an Outline of the Trip.--Following the definition of theme or story line, the next step is to consider how and when the various items on your inventory will be used to unfold the plot. In this, an outline is just as useful as it is for a formal talk. Keep in mind both the story line and the order in which the illustrative materials are encountered along the trail. You are under no obligation, however to point out everything seen from a trail, or to interpret the first pine tree encountered. Exercise your freedom of selection both as to what you will use, and when you will use it. The illustrative objects will not always occur in the logical sequence demanded by your outline. Perhaps you can alter the development scheme, or change your route of travel to improve the sequence. But do not be too concerned if you cannot develop a purely logical sequence. A conducted trip story does not have to be as formally organized as does a platform lecture. Nor does everything you see have to fit into the outline of your story. You do have a basic story to tell, and certain objects you see illustrate and develop that story. But there are side trips into other fields too. For example, perhaps you have planned the trip so as to develop the story of soil--its formation from rock, its first plants, its enrichment, its protection by plant cover, its function as a regulator of water supply, and the dependence of life upon it. True, almost everything you see might be related to this theme, but to avoid dragging everything into the picture, when you see a deer, drop the soil theme and talk just about the deer. Likewise, on a historical tour, or archeological excursion, the main theme is well defined. That does not prevent you, at suitable times, from mentioning conspicuous trees or flowers, or from pointing out interesting features unrelated to your basic story.

Discover the Conservation and National Park Aspects.--Now explore your activity for logical places to bring out and to illustrate related aspects of national park philosophy, objectives, use, and conservation. Keep in mind the dual objectives of interpretation--to reveal the facts and principles of natural and human history, and to do so in such a way as to serve the protection and conservation objectives of the Service.

A Conclusion.--Plan to bring the activity to a conclusion at a dramatic site, or an especially interesting or significant place. Don't let the event just disintegrate spontaneously. Make the end a climax. If the conclusion is at a dramatic scene, let the visitors get their fill of that scene first. Then, when attention swings back your way, bring the activity to its conclusion.

Summarize what you have discovered along the way, complete your theme, bring out the conclusions toward which your discussions have pointed, satisfy the suspense which has been created, or develop the inspirational aspects of the adventure. The following example, even though of limited applicability to other areas, will illustrate a conclusion that is both climactic and inspirational.

A very simple, natural, and most effective climax is reached at the end of a guided trip at Pipestone National Monument. Very casually during the trip, anticipation is developed for "the most beautiful and significant sight in America." The climax of the trip is reached as the party emerges from the limited view of the trail and, while the interpreter takes full advantage of the opportunity to comment on the significance of the area and of the national parks to America, the American flag comes into view. This sort of thing is not corny, forced, or emotional. Handled simply and with dignity, and related to the tone of the trip as a whole, it is most impressive and is certainly well received.

Now you have a plan and are adequately prepared. You are ready to meet your group and to put the interpretive plan to work. The balance of this discussion has to do with your actual presentation of the story as you meet your group and conduct them along the tour route.

A Conducted Trip is a Story in Serial Form

On the trail, the pattern of movement breaks up an interpretive story into separate parts. You stop, talk awhile, then proceed to another place to resume your talk. Even though you may have a good outline and a basic theme, the tendency is strong to permit the interpretive story to become a series of short stories, each complete but not necessarily related to the whole. A reader of a serial is motivated to read the next issue by interest generated in the current one, particularly by the suspense that is established by the development of unresolved situations just before he reads "to be continued." Use the same technique. Consider a conducted trip, not as an anthology of short stories, but as a serial story. Each episode is a completion of the one preceding, and a build-up leading to the next one, and each episode is related to a general plot that ties the whole together.

Drawing an analogy from the science of physics, a conducted trip can be thought of as a cycle of interpretation superimposed upon a cycle of movement. Keep the two cycles "out of phase." Begin the interpretive cycle with the introduction of a new idea before you move. At the next stop, complete the interpretive cycle, and make the transition to the second idea, again before the party moves on. Thus, the conclusion of an interpretive episode never coincides with the time to move, as there is never a logical place for people to lose interest or to drop out. Always, there is some unfinished business. Thus, you maintain suspense and develop anticipation for what lies ahead.

A Conducted Trip is a Directed Conversation

When you actually get on the trail with your party, forget the idea that a conducted trip is an illustrated talk. That was all right while you were planning how you would handle the event, but now you want to assume the attitude that you are participating in a conversation. A conducted trip is a directed conversation, not a speaker and audience situation. Even though circumstances compel you to do all the talking, the conversational attitude is a good one to assume. It helps you to identify yourself as part of a group, not a speaker before an audience, and to more consciously seek to secure participation of your group. Stimulate people to say something, do something, or think with you about something. These are the techniques of conversation, of participation. You will develop your own, but the following techniques are suggestive:

In the introduction, present a problem or a question to be answered--"Why does this stream flow, even though there is no melting snow to feed it?" "How are we able to date these ruins so exactly?" "What did these people do for water?" The purpose is to suggest the general theme, perhaps, but it also is to make people think and to stimulate curiosity and anticipation in what lies ahead. You point out a specific feature or raise a point, the full understanding of which will be revealed only as you complete the trip.

You can use questions that you ask or that are asked you along the trail to bring out some of your points. Sometimes you try to get the answers from the group, sometimes you answer directly, sometimes you let the answer be revealed by the objects encountered. Don't behave as if you are the only one who knows the answers. You may even feign ignorance part of the time when questions are asked you.

Make a game of your progress along the trail. The youngsters that crowd close behind you, especially, can be kept interested by a side activity for themselves alone.--"Who can spot the most kinds of trees?" "Find the first five-needle pine." Or, make the youngsters deputy naturalists, and give them some responsibilities such as keeping count of the party, passing out literature, or finding a specimen for you. Direct some of your questions to them.

Use a little drama.--"Around the next bend we usually see a family of beaver. Let's sneak up to where we can see them without showing ourselves. They will put on a good show if we are careful."

Encourage people to use all of their senses. Tell them to look, to listen, to smell, to taste, or to handle something. This is participation just as much as is a reply to your part of the conversation. Tell people to guess the depth of the canyon, the height of the Sequoia, the weight of a cannon ball, or the age of an arrowhead.

Let the people discover some things for themselves. Perhaps you have built up to the story of the water ouzel. Lead the group to a place where you know one will be seen, then let someone else see it before you do. Remember, you are not trying to prove how clever you are; your job is to help people to see for themselves, to pick up new facts, new ideas, and new concepts.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

training1/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 09-May-2008