|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Wallpapers in Historic Preservation |

|

HISTORY OF WALLPAPER STYLES AND THEIR USE

In the following section, an introduction to wall paper styles and history of their use will emphasize stylistic characteristics as further clues to the age of wallpapers, and provide guidance in choosing replacement patterns for buildings from which any evidence of the design of papers has disappeared.

GENERAL HISTORY

Traditionally, wallpapers have imitated more expensive materials, such as architectural details, painted wall decorations, wood grains, marble, and, most often, textiles. General stylistic trends, paralleling those of other furnishings and decorative arts can be traced in wallpapers.

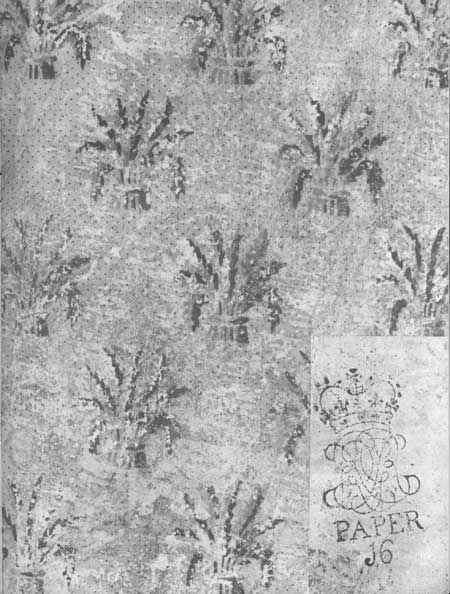

The face side of the paper was designed with a field of gray covered with greenish-blue sheaves of wheat. This design could date as early as 1795-1805.

The meaning of the marking "J6" is unknown.

Prior to the Revolution, English papers dominated the American market. Flocking was a specialty of 17th- and 18th-century English paper stainers, and its popularity was reflected in American houses. English flocked paper and canvas, with patterns of strapwork and scrolls, were used here in the 17th century. Floral patterned papers with flocking reflected 18th-century textile styles; formal symmetrical bouquets in flocked hangings were derived from damask-woven patterns, and patterns formed of branching stems putting forth flowers and leaves over backgrounds of diaper patterning were executed in flocking, as well as in distemper colors (figure 12). Other English floral patterns included some that featured flowing ribbons among the flowers, and floral stripes. Examples of each of these styles of 18th-century English wallpapers have been found in American houses.

|

| Figure 12: A red flocked version of an English flowering vine with diaper pattern survives from its 1781 installation in the Webb House built in 1752 in Wethersfield, Connecticut. The enormous size of the repeat, 72-1/2 inches long and 38-1/2 inches wide, contrasts with the narrow border, just under 2 inches wide. The scale is unexpected in a low-ceiled bedroom. Many of the horizontal as well as vertical seams between individual sheets of handmade paper, each about 21 inches wide and 24 inches long, are apparent in this photograph. (Courtesy of the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the State of Connecticut) |

Hand-painted, rather than printed, English wallpapers with large-scale nonrepeating views depicting ruined architecture are known to have been used in at least three important American mansions of the 1760's: the Philip van Schuyler and Stephen van Rensselaer Houses in Albany, New York, and the Jeremiah Lee House in Marblehead, Massachusetts. The elegant views were surrounded by wallpaper "frames."

A distinctive English pattern type was made of "pillar and arch patterns" (figure 14). These were recommended especially for use in hallways. These and many other 18th-century English wallpapers were generally monochromatic and subdued in palate compared to the French papers of the same and later periods. Many examples of grey papers, some with sparsely applied high lights of color have been found in this country bearing English tax stamps (figure 13).

|

| Figure 13: This paper with tax stamp found on the reverse side (shown in inset) was retrieved from the General Philip Schyler House near Albany, New York. Both are shown in full scale. Such a stamp, with the insignia "GR" (for "George Rex") could have appeared on any English wallpaper from the reign of King George I until the death of King George IV in 1830. It would be nearly impossible to determine the country of origin for such a simple repeating pattern without the English tax stamp. (Courtesy of the National Park Service) |

|

| Figure 14: Block printed in black and white on a gray ground, this English paper was probably the original wallcovering used in the Samuel Buckingham House, built in 1768 in Old Saybrook, Connecticut. The remnant illustrated is about 24 inches wide. Such relatively large scaled neo-classical "Pillar and Arch Figures" were advertised for use in hallways. A copy of this pattern, which differs from this one only in that the figures and every detail is exactly reversed, bearing the mark of a Hartford, Connecticut paper stainer of the 1790's is also preserved in the Cooper-Hewitt collections, illustrating the American practice of imitating imported papers. (Courtesy of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, New York) |

The end of British colonial trading restrictions cleared the way for a dramatic increase in the importation of French wallpapers to this country. Yet it was not until the 1790's that American advertisements began to feature the French paper hangings. Most distinctive of the French styles were the Arabesque patterns first popularized in Paris by Jean Reveillon (figures 15 and 16), and particularly admired in this country by Thomas Jefferson and his contemporaries during the 1780's and 1790's. Through the use of many individual blocks to print the large number of colors within a single pattern, Reveillon was able to develop a clarity of color and a subtle combination of brilliant and pastel shades that distinguish his wallpapers and those of his successors.

|

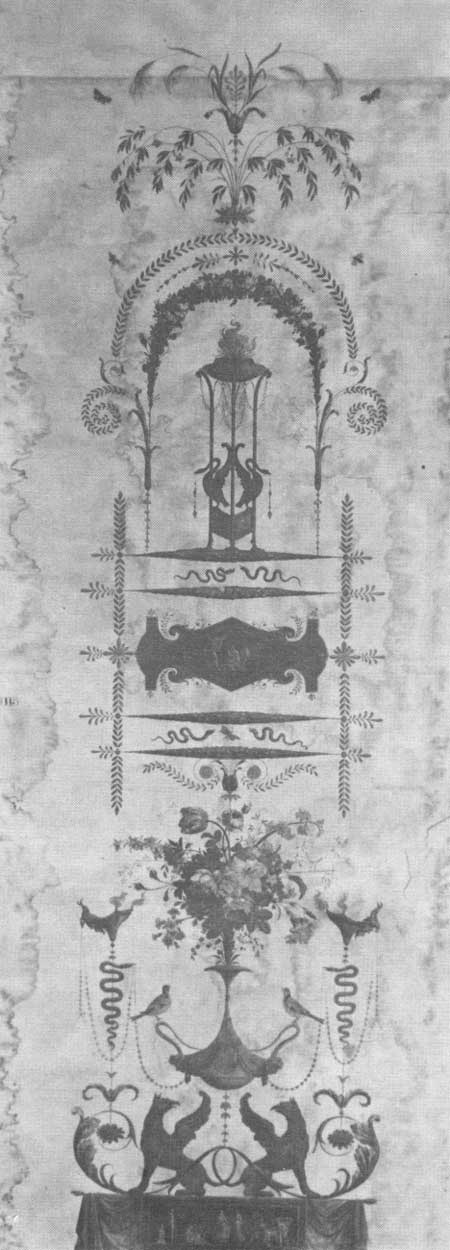

| Figure 15: This panel of wallpaper, after a design by Jean-Baptiste Fay, was block printed in the Parisian manufactory of Jean-Baptiste Reveillon about 1788. The Arabesque pattern shown here was rendered in multicolors on a cream ground. Vertical panels like this with its curious mixture of grotesque and naturalistic elements, all branching symmetrically from a central stem, reflected contemporary neo-classical styles. Designers of the Arabesque wallpaper panels like this one, apparently relied heavily on the wall decorations like those painted at the Vatican by Raphael. (Courtesy of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, New York) |

|

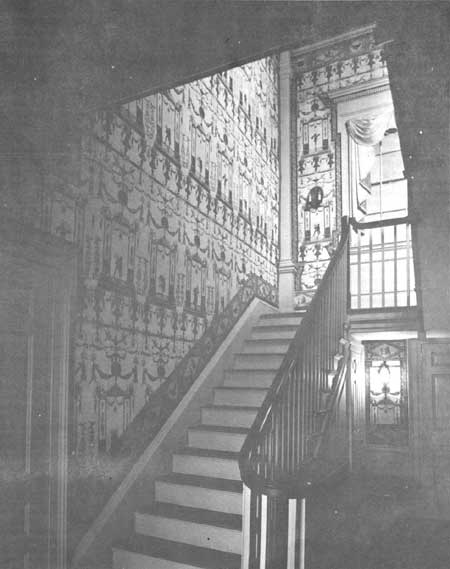

| Figure 16: Oliver Phelps had this paper and an intricate combination of borders hung in the hallway of a new wing he added to his Suffield, Connecticut House in 1795. The principal pattern was made in the manufactory of Jean Baptiste Reveillon, perhaps under the direction of Reveillon's successors, Pierre Jacquemart and Eugene Bernard. The incorporation of architectural elements and its large scale make this pattern comparable to English pillar and arch designs also popular for American hallways. (Courtesy of The Antiquarian and Landmarks Society, Inc., of Connecticut) |

Both the English and French styles were influenced by hand-painted nonrepeating papers exported from China to the West from the 17th century onward (figure 17). The expensive Chinese papers can be generally grouped into three basic types: flowering trees bedecked with birds and insects, landscapes, and processionals. Chinese papers were only hung in the houses of the richest Americans, but this trend filtered down; the incorporation of chinoiserie motifs in wallpapers printed by all the Western wallpaper manufacturing countries was common during the 18th century.

|

| Figure 17: Chinese craftsmen painted panels like this one in sets for export to the West where they were used as wallpapers. The rich of America made them particularly fashionable during the middle and later years of the 18th century. Elegant Chinese papers have been influencing Western taste in wallpaper design and craftsmanship since the 17th century, as they continue to do. The late 18th century example, which is shown here (43 inches wide), displayes white and pale yellow blossoms over a pale green ground. (Courtesy of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, New York) |

The earliest documentation known to the author for the printing of wallpaper in America appeared in the 1756 advertisement of a dyer and scourer "lately from Dublin," one John Hickey, who announced in the New York Mercury on December 13, 1756, that he "stamps or prints paper in the English manner and hangs it so as to harbour no worms." In 1765 another New Yorker, John Rugar, is recorded as having begun a wallpaper manufactory, and in 1769 Plunkett Fleeson, a Philadelphia upholsterer who had been in business at least since 1739, first announced that he had for sale "American Paper Hangings manufactured in Philadelphia ... not inferior to those generally imported." The American paper stainers based their patterns on imports, but despite their claims to excellence, they seem to have been held in low esteem by most consumers. The advertisement of one paper hanger published in 1785 is revealing: he offered to hang "any paper, from the most elegant imported from the East Indies or Europe, to the most indifferent manufactured in this country."

A late 18th-century style that lasted far into the 19th century featured the use of a plain solid shade of coloring applied to wallpaper, usually in green or in blue but available in a wide range of other colors as well. These papers were called "plain papers" and were usually advertised with "rich" or "elaborate" borders (figures 18 and 19). Walls painted in a solid color were also embellished with wallpaper borders; the "plain papers" had one advantage over paint—they hid the cracks.

|

| Figure 18: The watercolor Piano Recital at Count Ramfords, Concord, New Hampshire was painted about 1800 by Benjamin Thompson (Count Rumford). The plain green walls embellished with wide festoon borders at cornice level, and narrow edgings at chair rail level and around the door, were probably papered. They certainly illustrate the late 18th century taste for the plain colored wall with contrasting borderings, a fashion that lasted well in the 19th century. (Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch) |

|

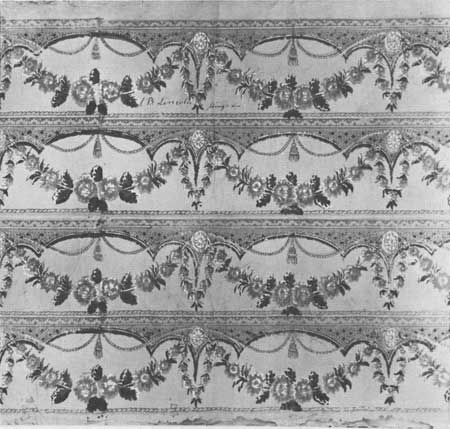

| Figure 19: Four lengths of festoon border survive uncut, side-by-side, as the paper stainer block printed them. They correspond closely to a border pattern illustrated on a late 18th-century bill head of Appleton Prentiss of Boston, who perhaps made them. Printed in orange, white, green, and pink on a gray ground, each border is 5-1/4 inches wide. Duplicates of the pattern in a variety of colorings, including one embellished with mica "spangles," have been found in New England Houses. (Courtesy of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, New York) |

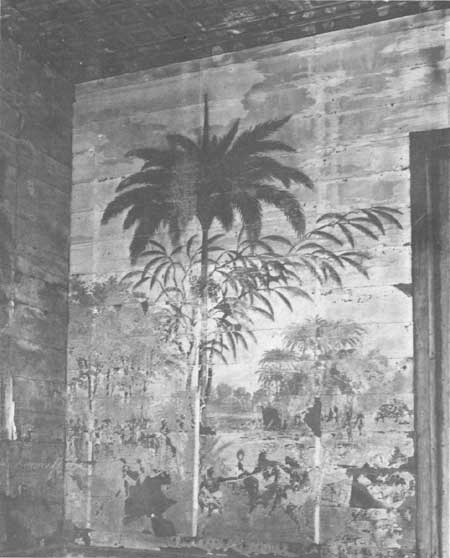

French styles dominated the American wallpaper trade during the first 70 years of the 19th century. In the early part of the century bright, strongly colored, even gaudy, Empire styles (figure 21) vied for attention with the spectacular nonrepeating "views" and "landscape" papers (figure 20).

|

| Figure 20: In the bedroom of a North Carolina house, this early 19th-century French "View" survived until the early 1940's when it was photographed in this lamentable state of repair. Though battered, it can be identified easily by comparison with Joseph Dufour's annotated illustrations published in 1804-1805 as the paper first made by Dufour in Macon, France. This celebrated paper depicted the voyages of Captain Cook, here shown on the Island of Tongatabo. It is apparent that the paper was hung directly on unfinished boards, a fact which contributed to its deterioration. The use of floral borders and of a paper imitating a coffered ceiling in conjunction with the scenic paper is particularly interesting. (Courtesy of Mrs. Wilson L. Stratton) |

|

| Figure 21: Shades of gray foil, vivid yellow and bronze shades in this bold French wallpaper dado which is 22 inches wide. It survived in a New Orleans House. A duplicate pattern with the drapery in blue can still be seen in the dining room at "Prestwood," a house near Clarksville, Virginia, where it was hung in 1831 on the lower part of a wall that boasted an elaborate scenic paper above the chair rail. (Courtesy of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, New York) |

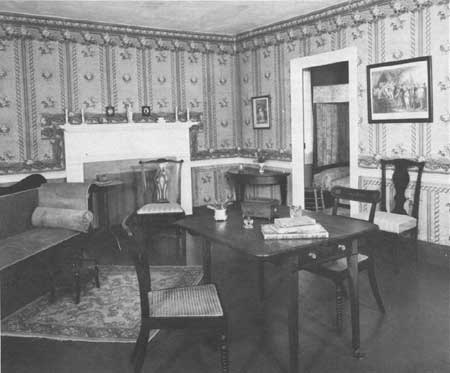

In the scenic papers, French block printers refined their skills in creating realistic imitations of paintings. In other wallpaper decorations, printers imitated drapery, sculpture, ornamental carving, plasterwork and other architectural detail. Simpler repeating patterns and stripes enjoyed steady popularity, and the French patterns served as models for American manufacturers. Bright powdery pastel shades were featured in many of the simpler patterns during the early part of the century (figures 22 and 23).

|

| Figure 22: The French wallpaper that was hung when the French-Robertson House was built about 1820 at Mille Roches on the St. Lawrence River in Canada survives in the house. The pattern of alternating motifs between widely spaced stripes (like that in figure 23) is typical of the early 19th century as is the use of borders at cornice and chair rail levels, and outlining the mantle. Some paper hangers' manuals suggest that borders served practically as well as decoratively: they covered up any gaps or irregularities should a length of paper be cut improperly, and helped to hold down the paper at the top where it might have begun to peel away from the wall. (Courtesy, Upper Canada Village, Morrisburg, Ontario) |

|

| Figure 23: An advertisement that appeared in a Hartford, Connecticut newspaper of 1821 shows simple stripes, closely akin to French papers from which they were doubtlessly derived. The simpler stripes flank another French wallpaper pattern type that was popular in America and copied by manufacturers here through the first 35 years of the 19th century. This central paper is also a stripe: the vertical lines of patterning at the edges of the paper width formed borders for a field of spotted, small-scale motifs which were the background for two larger motifs. These larger motifs, here flowers, alternated vertically over the entire length of paper. (Courtesy of the Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Connecticut) |

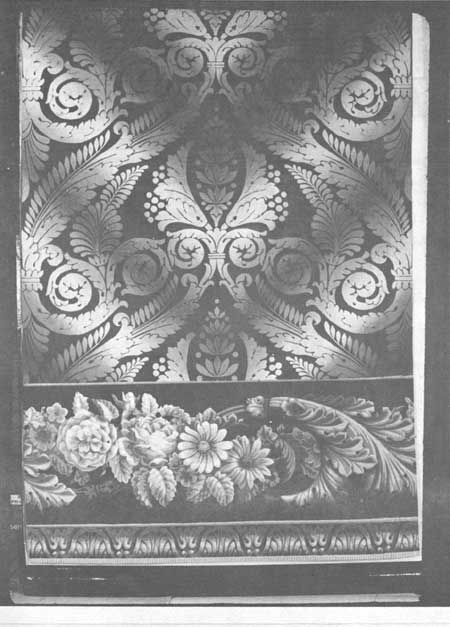

During the 1820's the Zuber factory in Alsace developed a printing technique that became a style in itself, widely imitated by European and American factories well into the 1840's (figure 24). The technique was one for printing subtle, blended color effects, called "irisée" by the French, and advertised as "rainbow papers" in this country. They resembled the ombré textiles of the same period, which were printed or woven with graduated alternating dark and light bands of the same or various colors. Factory records preserved in Alsace, document the dealings during the 1820's of the Zuber factory with a hundred American importers from Maine to New Orleans. The Zuber rainbow papers have survived in houses in New England, as well as the South.

|

| Figure 24: The shadowy chevrons of alternating darker and lighter tones shown in the repeating pattern above the floral border are deliberately contrived color shadings in tones that range from white, through yellow-gold to green. The color-shading technique introduced by Zuber et Cie, a manufacturing firm in Alsace, was very popular in this country during the 1820's-1840's. The Zuber Company, which is still in business, shipped these patterns to America in quantities. This pattern, found in a samplebook of 1828-1829 which is preserved in the factory archives, duplicates the paper found in the Calhoun house in Clemson, South Carolina. Sold here as "rainbow paper," the Zuber prototypes had many imitators. (Courtesy of the Zuber et Cie, Rixheim, Alsace, France) |

From the middle years of the century, elaborate Rococo Revival styles were peculiarly characteristic among the thousands of patterns annually offered by hundreds of manufacturers (figure 25). Using wallpaper, the Gothic Revival found its way into numerous domestic interiors during the 1840's and 1850's, while in many cases exteriors remained chastely classical. During this period, combinations of vivid green with grey, strong harsh red with brown, or a brilliant shade of blue paired with brown were particularly popular. Shiny, polished satin finishes for wallpaper had also grown in popularity since the beginning of the century (figure 26).

|

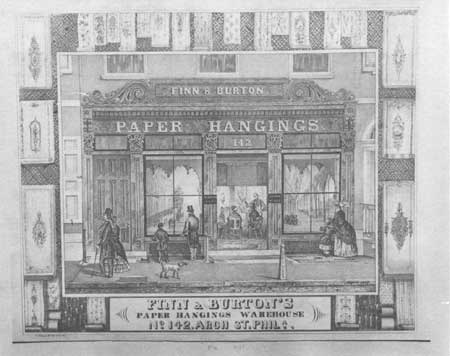

| Figure 25: An 1849 lithograph shows a Philadelphia wallpaper store with a wide selection of patterns ranging from scenes in the Gothic Revival taste, to Rococo Revival panels featuring elaborate scrollwork, to floral stripes and diaper patterns. Close inspection of the illustration will reveal that the diamond diaper pattern which forms the border background around the storefront in fact depicts rolls of wallpaper stored on a diamond grid of shelving. (Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia) |

|

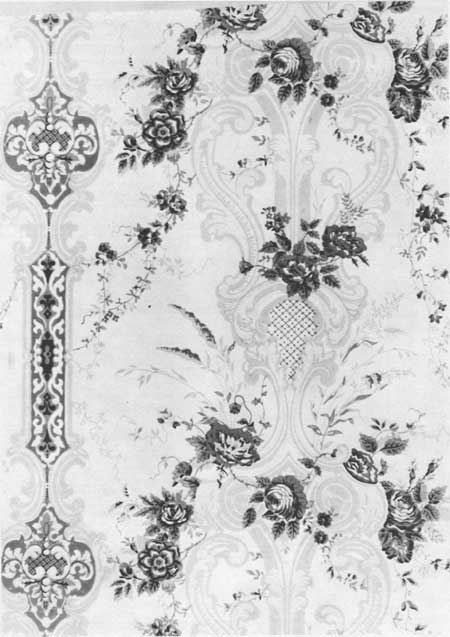

| Figure 26: On a mid-19th century stripe, realistic flowers were printed in bright blue, pink, and orange, shaded with maroon over scrollwork in gray, blue, and gold, all on a polished white satin ground. Typical of French imports of the period, this 22 inch wide paper was used in the Early House in Lynchburg, Virginia. (Courtesy of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, New York) |

The restoration of this paper to preserve it in place would have been so demanding and expensive as to render it impractical. It would probably have required that the paper be faced for removal, while a proper backing was prepared before it could have been rehung. Then a great deal of in-painting would have followed, so that the end result would have been little more than a newly painted reproduction. The alternative of replacing it with an antique copy of the same Captain Cook paper would have been the more practical and economical.

Scrollwork and miniature scenes appeared in profusion on wallpapers of the mid-19th century. Renaissance Revival styles competed with patterns of the other revival movements. Realistic flowers blossomed on many mid-Victorian walls (figure 27). There were also patterns for more sober tastes: in the 1850's and 1860's, papers featuring small embossed gold motifs, evenly spaced over grey or off-white grounds were considered very tasteful. Many of these embossed papers were imported from Germany.

|

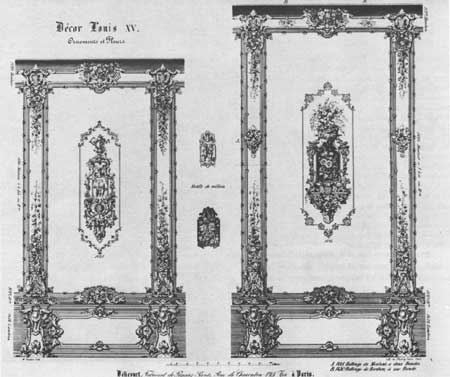

| Figure 27: Panel sets like the one shown here divided the walls of a room into vertical segments. They became fashionable in the mid-19th century. This engraved mid-19th century illustration shows a set by the Parisian firm Delicourt, a firm whose papers were prominently advertised in New York. Fragments of this design found in a house in Camden, Maine, are preserved at the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities. Panel sets were called "fresco papers" in the advertisements, and elaborate decorations in wallpapers like these are preserved in houses from New England to Mississippi. (Courtesy of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, New York) |

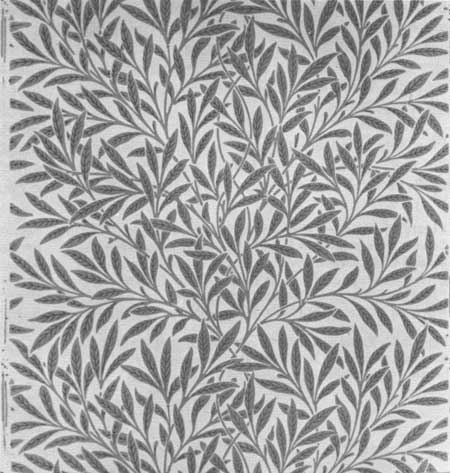

In the 1870's, English styles pushed the French ones aside and regained dominance of the fashionable wallpaper trade. Turning away from the elaborations and realistic painterly effects of French papers, Americans accepted the abstract and stylized flower patterns introduced by the English, and praised in Charles Eastlake's newly popular book, first published in 1868, Hints on Household Taste (figure 28). The impact of these new English designs was strongly felt at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia.

|

| Figure 28: The Englishman William Morris (1834-1896) designed this "Willow" pattern in 1874. It was one of the most successful of the stylized flat patterns—as contrasted to the naturalistic 3-dimensional patterns (like that of figure 26)—that won a generation of taste conscious Americans away from French designs. Morris papers inspired "artistic" imitations by American wallpaper manufacturers. Morris himself designed a total of 41 wallpaper patterns between 1861 and his death in 1896, and 5 patterns for ceilings. Because each was registered by name and number with accompanying sample at the English Board of Trade, and because these records are preserved in the British archives, the dating and identification of the designs of Morris, and of many other well-known British designers, can be quite precise. (Courtesy of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, New York) |

American taste-makers continued to endorse the stylized artistry of Englishmen like William Morris, Christopher Dresser and Walter Crane during the last quarter of the 19th century. The subdued, grayed palates of their patterns were particularly admired. In 1882 Oscar Wilde toured America, popularizing the English ideas about decorative design that included admiration for the exotic styles of Japan and the Middle East. In the wake of his visit, American wallpaper manufacturers popularized Moorish motifs, and a style known as "Anglo-Japanese" (figure 30). The patterns were rendered commercially in metallic golds, maroon, olive, black, and creamy yellow-beiges. Even on the most commercial level during the 1880's a degree of self-conscious interest in "good" flat pattern design and in abstraction was manifested that had never before been apparent and was soon to disappear.

|

| Figure 29: "Lincrusta-Walton" of the 1880's was preserved from the dining room of the John D. Rockefeller House in New York. In the thick, linseed-oil based composition material, highly embossed gold flowers on a dull red ground are stylized in the flattened abstracted "Aesthetic" manner that originated in London during the 1870's. Advertised as the "Indestructible Wall Covering," Lincrusta-Walton was first patented in England, and became so popular that its producers established a factory at Stamford, Connecticut. "Lincrusta" has lived up to its advertising, surviving in remarkably good condition in many stylish patterns in diverse settings: a log cabin in Leadville, Colorado, a Gothic cottage in Woodstock, Connecticut, and Mr. Rockefeller's New York mansion. (Courtesy of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, New York) |

|

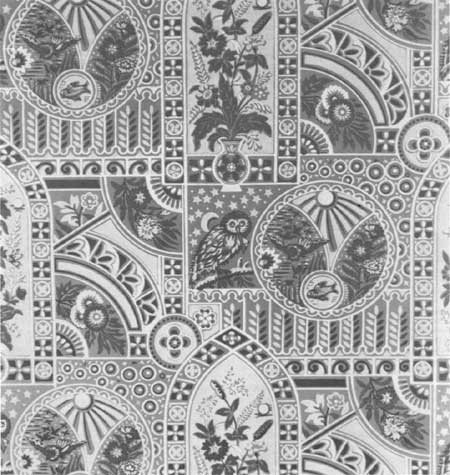

| Figure 30: In a commercialized American version of the "Anglo Japanese" style, owls, fish, and flowers, are all arranged in a strange asymmetrical configuration considered "artistic" in its day. Printed in maroon, yellow, light green, black, and olive on an olive green ground, this pattern is typical of quantities produced by American factories during the 1880's and into the 1890's. (Courtesy of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, New York) |

Three special types of late 19th-century wallcoverings were very popular. The first is "Lincrusta Walton," an invention of the 1870's made by an Englishman, Frederick Walton. Lincrusta is a composition, which like linoleum, is based on linseed oil. Very thick and strong, and patterned in high relief, it was sold both colored, and plain, to be painted after hanging (figure 29). In 1882 a company was organized to manufacture the English invention at Stamford, Connecticut. It was advertised during the 1880's as "The Indestructible Wall Covering," and had many imitators.

The second of these wallcoverings especially popular during the late 19th century was Japanese "Leather Paper." The final appearance of this product was so realistic that it fooled many a connoisseur into accepting it for actual leather. The heavy gauge paper was highly embossed and varnished, and featured richly colored and gilded decorations. It was not only hung on walls, but also frequently used to decorate the bamboo and imitation bamboo furniture that was popular during the period.

Finally, a third category of papers popular into the 1920's was "Ingrain" paper. According to the 1877 patent, the paper was to be made from mixed cotton and woolen rags, which were dyed before pulping. The process gave a thick, roughly textured "ingrained" coloring. Similar papers with rough grainy surface were known in the trade as "oatmeal papers."

Innovative flat patterns in the Art Nouveau taste had limited impact in America around the turn of the century. Some English designs continued to be bought by the design conscious avant-garde in America. But the 1890's witnessed a general return to commercial production of scrollwork and naturalistic styles not far removed from those of the mid-century. Commercial manufacturers leaned heavily on palates that featured saccharine pastel shades, and color blendings.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

wallpaper/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 26-Apr-2007