|

Lake Sharpe—Big Bend Dam Archeology, History, Geology> |

|

INDIANS OF HISTORIC TIMES, WHITE EXPLORATION AND SETTLEMENT

During the closing decades of the 18th century, the historical record of the Missouri River trench in the vicinity of Lake Sharpe indicates that it was the territory of two markedly different Indian groups. The Arikara (and the Mandan and Hidatsa to the north) were old residents, or so the long archeological record implies. These people lived a sedentary life in fortified towns and, despite frequent hunting forays into the open plains, their livelihood depended largely upon riverside fields of corn, squash and beans. The various groups of Dakota Sioux, on the other hand, were nomadic bison hunters who only recently had arrived in the area from their former homeland in the Minnesota woodlands to the east. The Dakota were predatory and more or less constantly in conflict with the sedentary villagers, notably the Arikara. It was not a question of political domination or territorial gain but of raiding for food or simply for scalps and glory.

All evidence points to a northward exodus of the village farmers out of the Big Bend area, leaving it to the Sioux (particularly the Yankton, Yanktonai and Teton groups), during the latter half of the 18th century, at about the same time the first Europeans reached the area. The earliest historical record is that of the La Verendrye brothers who led a party of explorers southward in 1742 from Fort La Reine on the Assiniboine River in what is now Manitoba. In the spring of the following year they met what are thought to be Arikara in the vicinity of the present city of Fort Pierre, South Dakota, and there, on March 30, 1743, buried an inscribed lead plate on a high point overlooking the mouth of the Bad (Teton) River. The plate was found there in 1913 and is today on exhibit at the South Dakota State Historical Society Museum in Pierre. By the end of the 18th century all of the village-farmers had moved or been driven upriver; in 1795 they were reported living in two villages on the Missouri just below the Cheyenne River some 30 to 40 miles above the Lake Sharpe region. The French fur trader Jean-Baptiste Truteau, on an expedition up the river, reported Sioux wandering on both sides of the Missouri at this time. In fact, while proceeding up the river in 1794, Truteau was waylaid near modern Fort Thompson by a party of Teton Sioux who relieved him of his goods, an experience many another trader would suffer in the ensuing years. Regis Loisel was another early trader who in 1802: in partnership with Jacques Clamorgan, the same merchant who had backed Truteau, built a fortified post (a "cedar fort") on an island in the river slightly more than 50 miles upstream from the Big Bend Dam in the La Roche vicinity. Loisel was accompanied by Pierre-Antoine Tabeau whose account of trading in the Dakotas stands as one of the best surviving records of the geography, wildlife and peoples of the region as they were in the opening years of the 19th century. But no single document has more historical importance than the detailed journal of the Lewis and Clark Expedition that records the journey up the river through the Big Bend area in 1804 and the passage downstream on the return trip in 1806. The story of the "Corps of Discovery" is one of the great epics of the American frontier, a part of which is related in the following section. By the time of Lewis and Clark, the Arikara had moved far to the north, settling in three villages a short distance above modern Mobridge, South Dakota; the Dakota Sioux held sway in the Big Bend.

During the first half of the 19th century the history of the Big Bend country, like that of the whole Missouri River and its tributaries, is very largely the history of the fur trade. It was a time when the trader, trapper, entrepreneur and mountain man opened the region for the later settler, cattleman and farmer. The trading economy was based upon the demand for furs and skins in the eastern United States and Europe. Beaver pelts were especially valued for the making of elegant hats but ermine, muskrat, deer, otter, fox and mink were also much in demand. The market for beaver peltries remained strong until the end of the 1830's when the increasing scarcity of these animals and changes of fashion led to a marked slackening of demand and consequent drop of the price of pelts. But the fur business continued into the 1860's, supplying in later years the demand for buffalo robes, hides and the furs of smaller animals. By the 1870's the vast herds of buffalo were much reduced; the next decade saw the virtual extinction of these once countless animals.

|

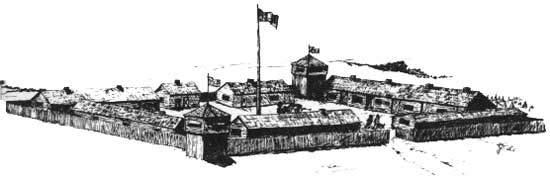

| Fort Pierre, field headquarters of the Upper Missouri Outfit of Pierre Chouteau, Jr. and Company of St. Louis, for many years one of the most important trading posts on the Missouri. This artist's reconstruction is based on a contemporary view and description. |

The first large scale fur expedition to ascend the river was promoted and organized by an aggressive St. Louis trader, Manuel Lisa. In 1807 he led a group of fifty to sixty men, in two keelboats with some $16,000 worth of trade goods, into present south-central Montana where, at the confluence of the Yellowstone and Big Horn rivers, he established a post called Fort Raymond. From this station, his hunters, trappers, and traders ranged widely over the country-side. In later years there was considerable competition among a number of companies for the upper Missouri fur trade and John Jacob Astor's American Fur Company emerged as the strongest on the river. Fort Pierre, near the city of that name at the upper end of the Big Bend reservoir area, was established in 1831 by the American Fur Company with the support of the powerful Chouteaus of St. Louis. This post, known as the Upper Missouri Outfit, became a center of operations, a supply point and storage depot for the company's activities on all the upper Missouri.

Typically, such isolated posts were protected with a stockade built of upright logs inside of which were log buildings or cabins to house the men, store the goods and other supplies as well as workrooms for blacksmiths, etc. Each trading-trapping outfit was in the charge of an agent or "bourgeois," such as Manuel Lisa, who directed the activities of all the men and was responsible to: and sometimes a partner with, the financial backers—the company. Under the bourgeois were the clerks who carried out various duties in the supervision of day to day operations. The main establishments, such as Fort Pierre, were self-sufficient and served as the headquarters for individual traders and trappers or small parties assigned to outlying posts. In 1833 the company at Fort Union at the mouth of the Yellowstone River, one of the larger, more important posts, had 12 clerks and 129 men on the payroll. They included tailors, tinners, coopers, blacksmiths, teamsters, boatmen, gunsmiths, hunters, and trappers. A few posts had cattle, hogs or even chickens and some maintained gardens; the name of Farm Island in upper Lake Sharpe derives from its use between 1831 and 1855 by the fur company at Fort Pierre. The company employees, called engages, were usually hired for a term of two or three years for a flat sum varying between one and five hundred dollars a year—room and board, such as it was, and equipment were furnished. The business of accumulating furs was in the hands of the trappers who ranged hundreds of miles from the post and the traders who dealt with the Indians at the post or elsewhere. A considerable variety of goods were kept on hand for trade and some items were stockpiled in large quantities at the main posts—tons of powder, lead and tobacco for instance. Other standard items included muskets and balls, gun flints, gun worms, powder horns, awls, axes, knives, files, shears, brass tacks, bar iron, kettles, tin cups, dippers, crockery, bowls, mugs, beads, ribbon, hawk bells, coat buttons, mirrors, combs, clay pipes, vermilion, blankets of various sizes and kinds, linens, calico, ticking, shirts, caps, sugar, coffee, tea and, almost always; illicit liquor. The price of these and other goods was not set in dollars but reckoned in terms of pelts, buffalo robes or the equivalent in some other item. Thus a horse might be valued at 30 robes or four cups of sugar worth one robe, etc.

Without question, the fur trading era was a boisterous one, enacted by men who lived a rugged, colorful, and often dangerous life. It lasted until the middle of the 19th century when the diminished market for furs and the much reduced buffalo herds led to a decline of the once flourishing trade. Both the Civil War and trouble with the Sioux adversely affected the Indian trade and during the late 1860's and 1870's much of the business fell to army sutlers (civilian suppliers under contract to the army) or to licensed traders at Indian agencies. And by the early 1880's the effective annihilation of the remaining bison herds signalled an end to the fur trade as an important industry on the upper Missouri.

The earliest major trading post in the Lake Sharpe region was Fort Pierre (also known as Fort Pierre I or Fort Pierre Chouteau) which was established by the American Fur Company in 1831 at a point just upriver from the present town of the same name. Here the so-called Upper Missouri Outfit prospered throughout the active fur-trading period; when the trade began to decline the post was sold, in 1855, to the Federal Government for use as a military fort. By that time the Sioux had become such a problem that troops were moved into the area under the command of the veteran Indian fighter, General William S. Harney. As part of his aggressive campaigning, he posted a garrison at Fort Pierre, but it proved unsatisfactory and only two years later the troops and movable stores were taken downstream by steamboat to Fort Randall. The period of steamboating on the Missouri corresponded approximately to that of the flourishing fur trade, each supporting the other. As well, the steamboat played a vital role in other development of the river; the American Fur Company steamer Yellowstone was the first to ascend as far as Fort Pierre, in 1831, the same year the post was established. The steamboat era reached its peak in the 1860's and 1870's when many thousands of tons of freight were moved but it did not survive the 1880's when rail transportation replaced river traffic. As a consequence of the demise of the steamer, a number of small but thriving villages along the river, which were dependent upon the steamboat trade, became ghost towns. The prominant St. Louis businessman Pierre Chouteau, Jr., came up the river by steamer in 1832 to examine the newly-built Fort Pierre, his name sake. That same year the famous American Indian artist Catlin arrived on the upper Missouri by steamer where he confronted many of the subjects recorded in his portraits. In 1833 the artist Bodmer in the company of Prince Maxmilian came up the river on the American Fur Company steamer Assiniboine and in 1843 the steamer carrying the naturalist Audubon stopped at a number of well-known establishments on the upper Missouri.

The upper Big Bend region was also the site of Fort George, a fur trading post of typical stockaded form erected in 1842 by Bolton, Fox, Livingston and Company to compete with the Chouteau outfit at Fort Pierre. The enterprise survived for only three years, after which the post was acquired by the Chouteau interests, the fate of most who attempted to compete with the Upper Missouri Outfit. Apparently Fort George was occupied by Indians for some years after it was abandoned by traders and to this day the surrounding neighborhood is known as Fort George.

|

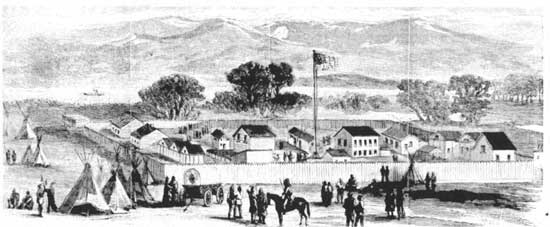

| A view of Fort Thompson as sketched by John Nairn, published in HARPER'S WEEKLY, October 28, 1865. The original site was immediately downstream from the Big Bend Dam. |

During the 1840's and 1850's a trading post was evidently in operation at the mouth of Medicine Creek, just above the Big Bend of the Missouri. However, the historical record is confused; the post was established either by rivals in defiance of Chouteau's Upper Missouri Outfit or by a trader named Bouis on behalf of Chouteau's company. The elusive post is therefore referred to as Fort Defiance or Fort Bouis. In either case, it may have been built in opposition to Fort George some 20 or more miles upstream.

Old Fort Thompson, just below the Big Bend Dam, was a stockaded establishment set up by the Federal Government in 1863 for the incarceration of the Santee (Eastern) Sioux and Winnebago Indians as an aftermath of the Sioux Outbreak in Minnesota the year before. Here these peoples were reduced to a wretched condition, which the Winnebago no doubt found especially demoralizing as they had no part in the Minnesota uprising. Within a few years, however, most of the Santee and Winnebago had left for or were removed to reservations elsewhere and Fort Thompson became the headquarters for the Lower Yanktonai Sioux established on the neighboring Crow Creek Reservation. Present-day Fort Thompson is in a new location on the uplands adjacent to the Big Bend Dam.

|

| Photograph of Fort Thompson (Crow Creek Indian Agency) about 1870. Note the tipis in the right foreground. (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service from an original in the National Archives). |

In response to hostile Sioux activities, General Alfred Sully was ordered to central South Dakota in 1863; this was the first of several years of campaigning through the region for the purpose of chastising the Sioux. Just east of present-day Pierre, on the mainland opposite Farm Island, he established a post named Fort Sully which was in use for three years until the garrison was moved some twenty-five miles upstream into the Oahe area. During its brief existence, the post served as a base for military operations, winter quarters and as a supply depot. Important councils with the Sioux took place at Fort Sully in 1865 and 1866 shortly before it was dismantled. The site of Fort Sully is marked today by a stone monument which may be seen south of Highway 34 as one approaches Pierre from the east.

The Red Cloud Agency at the mouth of Medicine Creek was a temporary establishment for the administration of the Oglala Sioux band led by Red Cloud. This group had been removed from northwest Nebraska in 1877 and was located on the Pine Ridge reservation in southwestern South Dakota the next year. During the intervening winter the Indians camped on the White River southwest of the agency at Medicine Creek.

The present towns of Pierre and Fort Pierre came into being at a fairly late date. It is said that one Joseph LaFramboise settled at the site of the city of Fort Pierre in 1817 but the town as we know it was not established until the 1870's. It is located at the mouth of the Bad River, known earlier as the Little Missouri or the Teton River, the scene of many important events in the history of the upper Missouri. In earlier years the settlement served as an outfitting and transhipping point for freighters destined for the Black Hills and other points west.

The town of Pierre came into being in 1880 as a railhead and frontier trade center. In its early years it could be characterized as a boom town and was a mecca for "ranchers, settlers, prospectors, gamblers, bull-whackers and outlaws." It was a thriving settlement when incorporated in 1883 and became the state capital six years later when South Dakota was admitted to the union.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

sec4.htm

Last Updated: 08-Sep-2008