|

PIPESTONE A History of Pipestone National Monument Minnesota |

|

|

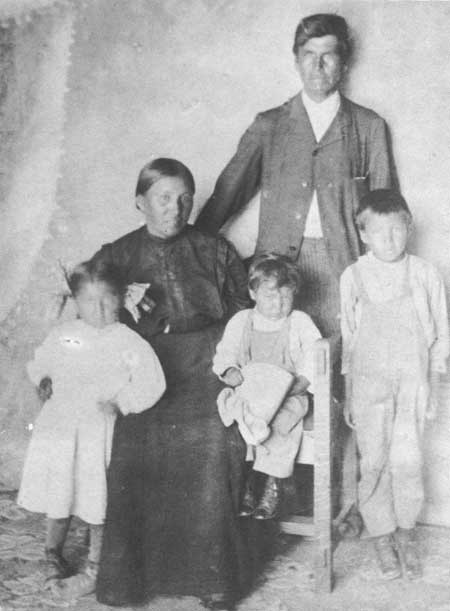

BACKGROUND TO ESTABLISHMENT OF PIPESTONE NATIONAL MONUMENT It is difficult to find an exact beginning of the popular desire to protect or develop the lands around the quarry for their historic and scenic values. Travelers of presettlement days noted the beauty of the area in sharp contrast to the monotony of the surrounding prairie. Early scientific visitors were impressed with both its geological features and the ethnological significance. Though writings of these visitors were important, the area admittedly owes much of its early popularity to George Catlin and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Whatever the ethnological short-comings of their works, they certainly captured the popular imagination of their day. Various editions of the writings of both men were in widespread circulation by the time settlers arrived at Pipestone. These early settlers were not without literary talent and ambition. From 1880 to 1895 they wrote much about the quarries. Drawing heavily from Catlin, Schoolcraft, and Longfellow, from tales told by Indians at the quarry, and from the inspiration of the scene, they left a mass of written works, most of which was published locally, either in booklet form or in newspapers. These have yet to be studied and evaluated. Most of the early efforts to preserve the Pipestone Reservation were aimed at protecting the quarrying rights of the Indians. One of the earliest references to the scenic values of the reservation reflects the attitude of a writer new to the prairies, longing for his timbered hills of home. An item in the Pipestone County Star of June 24, 1880, notes the beginning of tree growth near the creek and along the quartzite outcrop, and expresses the hope that prairie fires will "leave the place alone" for the next few years. A Minneapolis-St. Paul businessman visiting Pipestone in 1884 wrote a letter of protest to the Secretary of the Interior, calling the quarrying of quartzite from the outcrops "purely vandalism." Sometime before 1890, local opinion had grown strong enough that four of the petitions calling for establishment of an Indian school contained passages asking that a "National Indian Pipestone Park" be created there. In response, the first bill introduced in the Congress contained such a provision. As we have seen, compromises in committee caused an entirely different bill to be passed, which did not provide for the park. In 1892, a collaborator of the Bureau of American Ethnology visited the quarries, surveying and examining the ground. Local and Washington, D. C., newspapers heavily publicized this visit. W. H. Holmes, in the proceedings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science meeting in Rochester, New York, in August 1892, wrote that "The quarries are visited each year by about thirty families of Sioux Indians who travel some 200 miles from their reservation, spending a month or six weeks in camp about the quarries." In the summer of 1893, students of the Indian school made the first of many "improvements" on the reservation when they built a dam 200 feet long at the northernmost lake, "raising the water level considerably."

By 1895, park advocates were again active. In November of that year, the Pipestone County Star carried an editorial on the subject. Meetings were held extending over a 3-week period, after which a draft of a bill went to Congressman J. T. McCleary, who introduced it as H.R. 3741. It was to provide:

This bill died in committee. Early in 1898, the superintendent of the Indian school proposed removing the stone bearing inscriptions of the Nicollet-Fremont party and incorporating it in the structure of one of the buildings at the school. Protests by Pipestone citizens to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs promptly halted this move. The agreement of 1899, signed by the Yanktons but not ratified by the Congress, contained the following provision:

The efforts to obtain ratification of this agreement and the fact that it contained Article IV must have been responsible for the lack of efforts at further promotion of the park idea from 1900 through 1915. In 1916, an article in the Pipestone County Star renewed interest in a park by publicizing a plan, drawn by Ralph J. Boomer, for development of the reservation. Boomer was a local student of architecture whose plan envisioned a park conforming to then popular convention for a "highly improved, developed" area, emphasizing intensely concentrated recreational facilities. Though this plan itself was never acted upon, it influenced local thinking through the 1920's. During the early 1900's, before 1912, the most permanent "improvement" occurred. Indian schools of the period were to a degree self-supporting since they raised crops and kept livestock to provide as much food as possible for students. The superintendent of the Pipestone Indian School wished to increase the workable acreage of school farm lands. It was found that the rim of the falls on Pipestone Creek was higher than lands immediately upstream on the reservation, and it was believed that lowering the falls would bring an additional 18 acres to a workable condition. An appropriation of $3,500 was obtained, and a channel blasted through the quartzite ledge, lowering the rim of the falls. In later years, landowners living upstream from the reservation took advantage of the changed stream gradient, and straightened and changed the grade of Pipestone Creek throughout most of its length. Beginning in 1919, a movement was launched to make a small tract of reservation lands into a city park. Ellsworth E. Beede led a drive for funds which was supported by the Pipestone Businessmen's Association. The general plan called for acquiring 22 acres around the small lake toward the northwest corner of the reservation. It included also the development of swimming facilities, with a bath house and graveled beach. The drive netted $600, and the bath house was built, with the tolerance of Indian school officials. However, inquiry by Congressman Frank Clague revealed the unsettled land title, and here the project ended. The biennial report of the State Auditor in 1923 presented a list of potential State parks to the Minnesota Legislature. One of these areas was the Pipestone Reservation. Increasing interest and visitation led the Indian school superintendent to erect bulletin boards displaying the regulations for the area, and warnings as to penalties for violations of the Antiquities Act.* He also announced plans to fence the Nicollet marker.

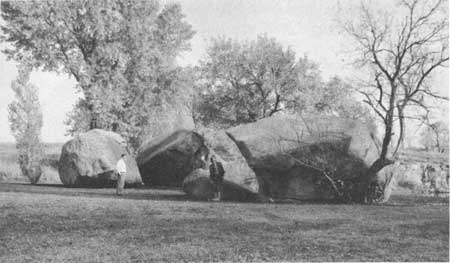

During this same year, the Daughters of the American Revolution campaigned to preserve wildflowers on the prairie lands of the reservation. Soon the Governor of Minnesota directed the Highway Commission to make a survey of the reservation to evaluate it as a possible State park. While this was underway, the local post of the American Legion organized a volunteer force which cut weeds around the falls and improved the first small lake below it. By December, the State released its survey report. This report suggested that the State acquire 24 acres of land centered around the falls. It provided an outline for the then popular "intensive development" of this tract, including picnic grounds, a bathhouse, an outdoor theater, and an American Legion lodge. Pipestone citizens greeted the report with enthusiasm, and formed the Pipestone County Park Committee to promote the idea. In January 1925, H. J. Farmer and L. P. Johnson introduced a bill in the Minnesota Legislature to establish a park, conditional upon transfer of the required land from the Federal Government. The bill passed, but the park could not be established because the unsettled title made the land transfer impossible. In September 1925 the Daughters of the American Revolution placed a bronze plaque on the stone bearing the Nicollet inscriptions. It then sought to protect the Three Maidens area along the southern boundary of the reservation by purchasing a purported title to this tract from Staso Milling Company of Chicago. This title was transferred to the city of Pipestone in 1928.

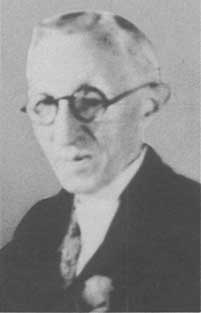

Once the reservation title was settled by payment to the Yanktons, local individuals and groups renewed their interest in establishing a park. In November 1929, the DAR passed a resolution favoring the establishment of a national park or monument. Local efforts to promote this idea were coordinated at a meeting at the Calumet Hotel in Pipestone on January 14, 1932, and attended by representatives of civic, religious and fraternal organizations and of local governmental agencies. Some 53 local organizations were represented. Officers elected were Winifred Bartlett as president; Edward R. Trebon, vice president; Tad A. Bailey, secretary; and Max Menzel, treasurer.

The executive committee of the organization approved a draft of a bill to establish a park. It proposed a park of 81.75 acres and granting of quarrying rights to Indians of all tribes. (No Indian quarrying rights remained after the Government acquired land title.) Superintendent James W. Balmer of the Pipestone Indian School was asked to sound out Bureau of Indian Affairs opinion of the project when next in Washington. Balmer reported that certain officials of the bureau objected strongly to the park idea, and had no doubt been influenced by the proposals of the early 1920's. Accordingly, the name of the organization was changed to the Pipestone Indian Shrine Association, and emphasis shifted to the historic and ethnological values of the area. The balance of March and most of April 1932 was devoted to work on a booklet entitled The Pipestone Indian Shrine. It was widely distributed to promote interest in the project. Charles Berry, a field representative of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, appeared at a late April meeting of the organization to discuss the proposals. He and Superintendent Balmer submitted a joint report emphasizing the difference between current proposals and those of 10 years before. They closed the report by highly recommending the establishment of such a park.

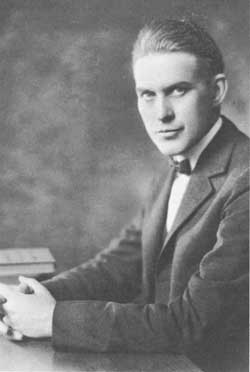

In July 1932, the National Park Service prepared a brief of the land status, history, and significance of the area. Armed with this information, E. K. Burlew, administrative assistant to the Secretary of the Interior, visited Pipestone, toured the reservation, and indicated that the National Park Service would investigate the proposal in greater depth. In October 1933, Miss Bartlett contacted both the Director of the Park Service and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs regarding the Monument proposal. Concerning the probable impact upon Indian school activities, the Commissioner stated that the required area of land would not interfere with school operations. Late in 1933 and early in 1934, the Civil Works Administration began development of the roads bordering the reservation. Included was a stretch of road from the junction of Hiawatha and Reservation Avenues west to the Three Maidens area. An Indian emergency conservation works program began on the reservation in January 1934. Under the general supervision of Superintendent Balmer, this project used Indian labor as much as possible. Plans called for road construction, fencing, planting trees and shrubs, and construction of a dam on one of the lakes just outside the proposed park. R. W. Hellwig took over detailed supervision of the work, and the city of Pipestone agreed to furnish 100 white elm trees and $100 for additional trees and shrubs to complete Hellwig's planting plan. Formal legislative efforts to establish the area as a unit of the National Park System began in May 1934 with the introduction of S. 3531 by Senator Henrik Shipstead. This bill went to the Committee on Public Lands and Surveys, who sent a copy of it to the Secretary of the Interior for an opinion. Studies did not reach the report stage during that session, and no further action was taken on the bill. On January 22, 1935, Senator Shipstead introduced S. 1339, similar to his earlier bill. Active Park Service investigations began that year, and in August the reports of investigations by Landscape Architect Neal A. Butterfield and Historian Edward A. Hummel were completed. The Public Lands Committee submitted a favorable report, the Senate passed the bill, but the House did not act upon it.

Congressional action renewed in January 1937, with the introduction of S. 1075. The Department of the Interior report on this bill recommended that the name be changed to Pipestone National Monument, that certain boundary changes be made, and that quarrying, rather than mineral, rights, be reserved to Indians of all tribes. The bill passed the Senate on August 6, and the House on August 21. On August 25, 1937, President Franklin D. Roosevelt placed his signature on the legislation, and Pipestone National Monument became a legal reality. |

|

| ||

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

A History of Pipestone National Monument Minnesota ©1965, Pipestone Indian Shrine Association pipestone/sec7.htm — 04-Feb-2005 Copyright © 1965 by the Pipestone Indian Shrine Association and may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the Pipestone Indian Shrine Association. | ||