|

CASA GRANDE

The Casa Grande National Monument |

|

THE CASA GRANDE RUINS

By

FRANK AND EDNA PINKLEY

THE MUSEUM

It must be remembered that in the nature of the case any museum collection gathered from the Casa Grande ruins will be more or less incomplete. This type of ruin will not preserve the perishable material for six centuries after abandonment, and we may well expect to find many more specimens of pottery, stone, bone and shell objects than of cloth, wood, tanned skin, etc. This will be largely due to the fact that soon after abandonment the roofs disintegrated and allowed the rains to penetrate, rotting out a great deal of the perishable material. The museum collection includes two or three pieces of cloth of surprisingly fine weave and showing what is now called punch work embroidery. At least one of these pieces is of cotton which, taken with the reported discovery of cotton seed, is fair evidence that cotton was raised under irrigation in the Gila Valley long before the discovery of America.

Corn is one of the highly perishable materials under the conditions which obtained here, but has been found in a charred condition in widely scattered places in the village.

No evidence pointing toward the raising of beans has yet been uncovered and it is possible that the people depended on the Mesquite for beans.

Bone carving and shell carving seem to have reached a high stage of development in the very early period, and some very good examples of shell carving may be seen in the museum.

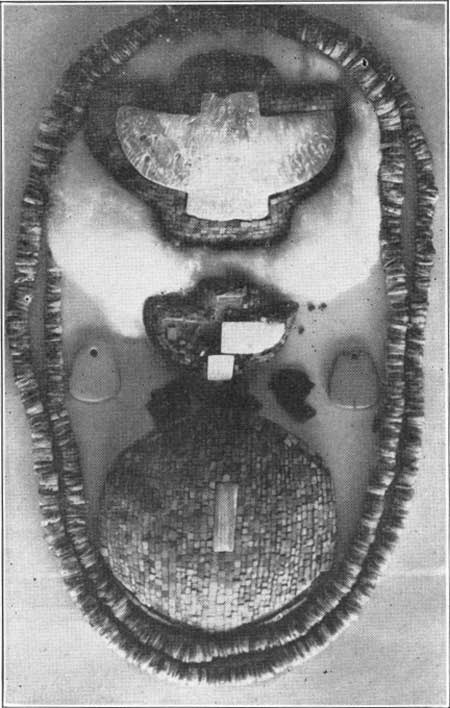

Undoubtedly the finest single find in the museum is the group of inlaid turquoise objects with the accompanying necklace, ear bangles and bracelet. This is supposed to be a ceremonial set of jewelry and is the finest thing of its kind which has yet been found in the United States. The inlaid pieces are supposed by the experts to be of turquoise from the country south of Santa Fe, New Mexico, while the two bangles are said to have come from the mines of Nevada. If this be true it would indicate a considerable trading range.

|

| Turquoise and Shell Inlay and Shell Beads (Photo Courtesy National Park Service) |

Another evidence of trade over a considerable distance is the series of copper bells in the collection which are said to have been manufactured by the Aztecs down in the Valley of Mexico. These small copper bells are found pretty generally over Arizona and New Mexico but none of them are thought to have been made in either state.

The so-called "Square and Compass" emblem, which is carved from a sea shell, has aroused wide interest. It was found about 1925 in the eastern edge of the Casa Grande Village about four feet down in a trash mound of the red-on-buff period and the indications are that it was made by the ancient inhabitants about 1,800 years ago.

Several strings of beads will be noticed in the collection, some of them quite small. These beads are made of shell, clay and stone and were evidently worn as jewelry. Shell bracelets can also be seen as well as shell rings and pendants. The shells from which all these things were manufactured, were brought in by the Ho-ho-kam from the Gulf of California some 175 miles distant, and must have been considered pretty valuable even in an unworked state as it was a perilous matter to make the long journey on foot through the desert country where there was no living water. One finds such a constant association of the shell and water as to feel pretty certain that the people made the trip themselves and did not simply trade the shells from their neighbors to the southwest.

The pottery divides normally into three major classes; the red-on-buff, the black-on-white and the polychrome.

The red-on-buff is, so far as we now know, the earliest type of decorated ware to be used among the potters of the Gila Valley. I think we are safe in saying its use goes back at least two thousand years, and several sites are now known where only this type of decoration was in general use.

Several hundred years later we find the black-on-white pottery coming into use and from thence onward the red-on-buff and black-on-white types run along together, the red-on-buff predominating.

Still later we can mark the entry of the polychrome; not long before the period of abandonment, and in this later period we have all three types mixed in the trash mounds, but the red-on-buff seems always to predominate.

|

| The So-called "Square and Compass" |

Examples of all these types of pottery may be seen in the museum and the visitor is given the theory of their origin and use as well as an explanation of the various sub-types into which the main types can be divided.

Among the stone artifacts the stone axes invariably attract the attention of the visitor. It is a widely held popular belief that the stone axe was made primarily for war use. Among the Ho-ho-kam the axe was probably not carried in war to exceed two or three weeks in the year and for the other fifty weeks must have been used for very much the same purpose to which we put the steel axe of modern times. With it they cut their wood, drove stakes and did the various kinds of farm work.

While not so spectacular in appearance, the stone digging tool was much more important in the lives of the Ho-ho-kam and many specimens may be seen in the museum. These flat stone slabs were probably used in pairs, one in each hand, and with them the dirt dug out and thrown into baskets or skin bags for transportation. In this manner ditches were excavated which were eighteen or twenty feet wide, six or eight feet deep and fourteen to twenty miles long. Study over that a while and you will begin to see what we mean when we tell you these Indians were a very busy people; to do the things they had to do with the crude implements they had, must have taken about all the time there was available.

Good examples of the metates, or stone mills upon which the corn was ground, may also be seen in the museum. The stone mortars were probably not used for corn grinding but for breaking up mesquite beans, acorns or pine nuts. For grinding purposes the ancient people preferred to use the volcanic rock because it, being porous, would remain rough by the virtue of wearing new holes in the rock as the old ones were worn down, thus never needing re-sharpening or re-dressing.

A visit to the ruins and the museum leaves one with the feeling that the modern white man need not feel so smug about having recently brought the Gila Valley under cultivation in these days of steam, steel, and electricity when the ancient Indian lived here by irrigation for more than a thousand years with no draft or pack animals, and with no metal tools.

These people had no particular lost arts; we can duplicate the things they did, but we would have trouble in getting the modern American to duplicate the infinite patience they used.

| <<< Previous | Next >>> |

pinkley/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 16-Apr-2007