| The War in the Pacific |

|

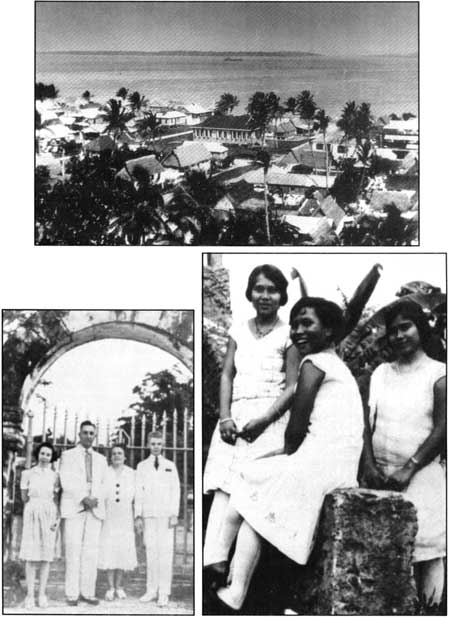

LIBERATION — Guam Remembers A Golden Salute for the 50th anniversary of the Liberation of Guam

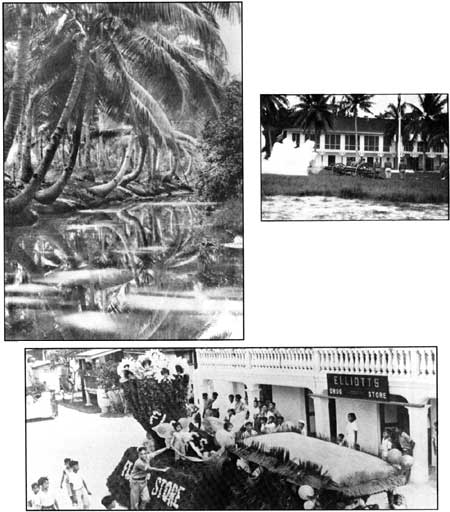

Guam obstacle to Japan's ocean empire In pre-World War II Guam, life was generally as it had been for decades. Except for the presence of those responsible for the naval administration of the island, Guam was basically a land of farmers and fishermen, the people living a simple lifestyle where they met their essential needs. So when war came to this kind of community, this kind of society, it was devastating, bringing unstoppable change. The first war to visit the island and its people came in the Spanish colonization. Though Ferdinand Magellan had come upon the island in 1521 and the explorer Legaspi had "claimed" Guam for the Spanish crown in 1565, it was only in 1668 that the Spanish attempted to colonize the isle. In that year, Guam found itself the focus of Catholic missionaries, notably the padre Luis de San Vitores, and their accompanying military protectors. The effort to bring Catholicism to the island was successful - today, the great majority of the people call themselves Catholics - but the price to Guam and its native people was costly. The resistance of the indigenous people to the Spanish resulted in conflict and war with the Spanish military. So by the time the United States came unto the island in 1898 in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War, the war of colonization and disease brought by Western man reduced the native Chamorro population from a high of perhaps as many as 100,000 people in 1668 to 9,000 by 1898.

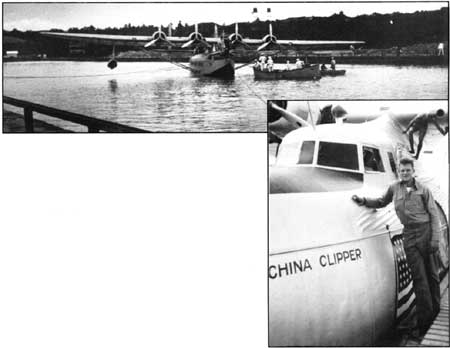

By 1898, the people and the island were at peace, but both people and island were neglected by a Spain whose empire was fading into history. In spite of America's rise in power and influence around the world, the life of the people of Guam saw relatively little change in the transition from being one nation's colony to being a possession of another. A great part of the reason for that was the ambivalence, and ignorance, of the United States toward the Pacific and Oceania. As a result, of all the Spanish islands of the Marianas, only Guam was taken as a spoil of war under the Treaty of Paris between Spain and the United States. Spain retained the northern Mariana islands - Saipan, Tinian and others - and sold them to Germany in 1899.

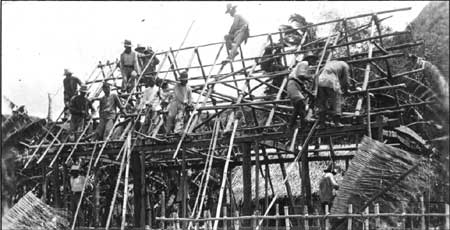

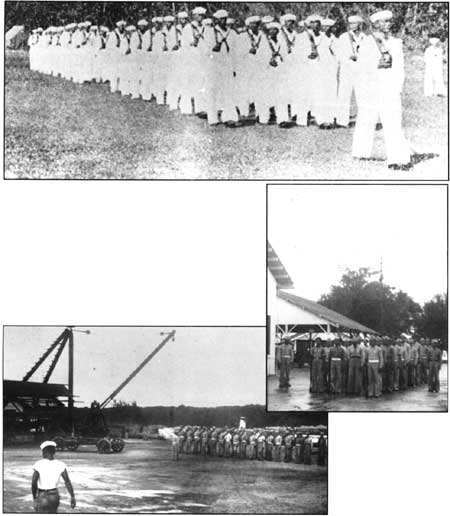

Because Guam was merely looked upon by the Navy as a coaling station for its ships as they sailed the Pacific, the island changed little, although the military did add to the economy by buying from farmers and fishermen and employing people. Naval administrators of the island did initiate and sustain typical government departments such as schools, a hospital, courts and police, but overall the island's lifestyle changed little.

Chamorros had gained in terms of democratic government; a House of Assembly served as a legislative body but it was merely advisory. Chamorro self-determination was non-existent. The naval governor still possessed absolute authority - he was legislator, chief executive, judge, all under one hat. Japan, though, was much more active in its efforts around the Pacific islands. When the opportunity arose in World War I as Germany was reeling from its defeats in Europe, the Japanese were unfurling the flag of the Rising Sun in German-held islands above the equator. Their presence in the central and western Pacific was vast, as vast as the area of the continental United States: from the Marshall Islands in the east, to the Carolines, to the Marianas and anchoring the line of Japanese-occupied islands was the Palau archipelago. In the Treaty of Versailles which ended World War I, Japan's occupation of these islands was formalized under a mandate of the League of Nations. Japan wasted little time in solidifying its claim to these islands. The Japanese, who had a strong economic presence in the islands even before World War I, was now sowing its influence upon the islands through schools, agricultural programs, and, what would later prove deadly to American Marines and soldiers, the fortification and buildup of the islands as military installations. With little political or financial support coming from Congress to fortify Guam, the United States signed an agreement with Japan in 1921 at the Washington Naval Conference. The two nations along with other world powers agreed not to fortify their possessions in the Pacific. However, Japan's designs on the islands began taking on a militaristic tone, and by 1935, the country refused inspection of the islands under the mandate and walked out of the League of Nations. The action was typical of Japan in those times as the nation, causing worry and concern for all those in Asia and in the Pacific, was growing more and more committed to a policy of aggression. Only then did the United States begin thinking of fortifying Guam, and in 1938 a Navy study did recommend that the island's naval facilities be improved to the point where they could support a fully-equipped and operational fleet to help in the defense of the Philippines. But the price tag - possibly tens of millions of dollars - needed for such a buildup was considered too high. It was in this atmosphere that in December 1941 the people of the United States and Guam began paying - in blood - for a war that suddenly swept the nation and the island into years of struggle, years of sadness, years of tragedy.

|