|

Navajo

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER IV: "LAND-BOUND:" 1938-1962

Between the end of the 1930s and the early 1960s, the pace of change on the western part of the Navajo reservation began to accelerate. More and more of the accouterments of the outside world were available, and with the exception of the war years, the steady stream of visitors increased. Roads began to traverse the region, and both the monument and the people around it began to experience more of the outside world than they ever had before. The isolation that previously characterized the monument diminished, and the modern world intruded on it in many ways.

As the pace of life on the western Navajo Reservation quickened, a growing sense that the monument was more than surrounded became common among its superintendents. Both in the regional office and at the park, NPS personnel realized that the location and lack of space at the monument constricted their ability to manage and protect it. Park managers felt increasingly "land-bound," in the words of long-time superintendent Art White, hampered by the non-contiguous nature of the monument and its dependence on the surrounding Navajo people. As development reached northeastern Arizona, the NPS at Navajo was forced to respond in a reactive manner.

The NPS response was gradual, limited by funding and the historically low priority of the monument in the park system. A slow alleviation of the lack of accessibility began the process of bringing Navajo National Monument to the attention of the public. Post-war road building programs brought automobiles within easy reach of the monument, forcing park managers to address the problems engendered by rising levels of travel throughout the Southwest. Yet the limitations on staffing and programming remained, and superintendents felt the pressure of being asked to do more with less. Area Navajos became an increasingly important asset for the monument as the area developed.

Yet the actions of the Park Service were responses to situations rather than proactive measures. By the middle of the 1950s, superintendents and regional office officials recognized the need for preparation for the coming changes in northeastern Arizona. Little notice of this need followed at the national level, even after the beginning of MISSION 66, the system-wide capital improvement program inaugurated in 1956. As a result, the planned and executed developments at Navajo lagged behind the need for facilities, creating a situation typical in the park system prior to the 1930s: NPS developments responded to immediate needs and did not lay the basis for long-term planning.

The arrival of James W. and Sallie Brewer late in 1938 began a new era at Navajo National Monument. Trained by Frank Pinkley and previously posted to Aztec Ruins National Monument in New Mexico, the Brewers were the first NPS professionals to manage Navajo. John Wetherill had served in his day; he guided the few hardy archeologists and travelers to the ruins. But the needs of the late 1930s were more comprehensive, and the Brewers brought Pinkley's training and philosophy to the last of the volunteer-run southwestern monuments.

The conditions they found were primitive. When they came, the only structure at Betatakin was Milton Wetherill's boarded tent, stocked with provisions he had left. Wetherill had been the only person to spend a winter in the canyon. The Brewers quickly decided that they could not follow Milton Wetherill's lead and passed their first winter in one of the large stone hogans at Shonto Trading Post the first winter. They cooked in a tent, for Harry Rorick did not permit cooking in the hogans. When the trail to the monument was free of snow, Jimmie Brewer frequently made the ten-mile trip in an old beat-up pickup truck. But heavy snows closed the trail in January and February, and the middle of March arrived before Brewer could make his way back.

By the middle of April, the Brewers settled at the monument. The first headquarters was a tent by Tsegi Point. Water came in a 55-gallon drum from Shonto. When it did not suffice, they went to a nearby seep discovered by Navajo mules. A horse named Messenger, left to the Brewers by John Wetherill, provided the primary means of transportation. Many evenings when the 55-gallon barrel was empty, Sallie Brewer rode Messenger to the seep for more water. Laundry posed another problem. Sallie Brewer later reported that at Navajo she "learned to wash clothes in strained, reheated dishwater." [1]

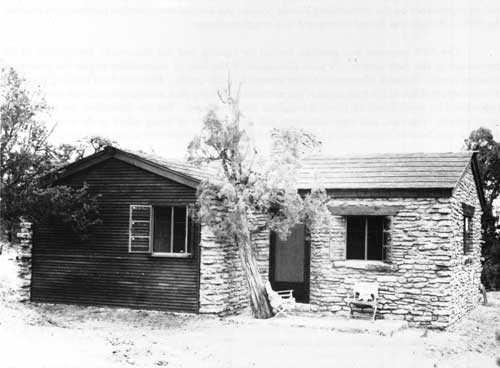

Part of the lure of the position had been the promise of a new residence, to be built the first year the Brewers were at Navajo. The tent was near the site of the proposed residence. Indian CCC labor built a two-room cabin in 1939, the same year they drilled a well, the first CCC work since the CWA project in 1933-34. The one-bedroom house was "beautiful," according to Sallie Brewer, who fondly recalled moving into it, but the complicated canyon sump-vertical pipe hole-rim pump-storage tank water system did not begin to function for another year. [2]

The new custodian's residence built in 1939 was

the first permanent housing at Navajo.

A characteristic pattern of development began, albeit much later than at most park areas. As occurred elsewhere in the Southwest and across the nation, the installation of a professional Park Service person was only the first step in a plan of development. It was followed with a residence, and in many instances an administrative building, museum, or visitor center. But by the time the residence was constructed at Navajo in 1939, most of the rest of the park system had already been developed. During the 1920s, the major national parks constructed many of their amenities; most other areas were developed in the capital-program oriented phases early in the New Deal. By 1939, there were few park areas for which the NPS had plans that did not already have some kind of large-scale program underway. Despite the construction, Navajo remained at the far end of the world of the Park Service.

There were so few buildings at Navajo that the

custodian had to have his office in the living room!

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

nava/adhi/adhi4.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006