|

Lincoln Boyhood

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 9:

Interpretation

When Lincoln Boyhood's first superintendent, Bob Burns, arrived at Lincoln City in mid—1963, he faced the tremendous tasks of defining the role of the national memorial in the community and establishing its interpretive programs. Burns made the two tasks one. His stated objectives for the park's first year of operation were to inform the public concerning the National Park Service, its programs, and its services; to publicize Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial; and to inform the public about Abraham Lincoln's boyhood years (a shift from the prior decades, which focused on Nancy Hanks Lincoln's death and gravesite). [1] Burns' first major step was the initiation of a series of television programs on station WTVW (channel 7), an Evansville station, as discussed in Chapter 6, above. Sponsored by the Southwestern Indiana Educational Television Council, the programs continued for two years. A partial listing of the subjects of those programs is contained in Appendix D.

The television programs were remarkably successful in acquainting the public with the National Park Service and the differences between the Service and the state park system. The programs brought the park's interpretive programs to a wide audience and created public support for the new area. While residents of southern Indiana were well aware of the western "jewels" of the National Park System, Burns' television programs made them equally familiar with the "gem" close to home. [2]

Superintendent Burns enjoyed firm and friendly working relationships with area newspapers, resulting in frequent articles and positive editorials on events at Lincoln Boyhood. Burns often wrote the articles published in the nearby Dale, Indiana, News. In addition to spreading the word about Lincoln Boyhood and the National Park Service, Burns used the television and newspaper contacts to request donations of Lincoln—related materials. [4]

In 1964, he initiated evening programs at Lincoln State Park to supplement the interpretive programs at the national memorial. He also began permanent staffing of the visitor contact desk that year. [5] Burns also worked toward the development of a quality brochure, and persuaded the Washington Office to allow him to order a more sedate and appropriate cover for the folder than the conventional blue and yellow lightning bolts used on most park folders in the early 1960s. [6]

Both Bob and Vivian Burns were active in the Lincoln Hills Arts and Crafts Association, a local arts and crafts organization which chose Mrs. Burns as its first president. Mr. and Mrs. Burns learned to spin with a 125—year old spinning wheel, and gave demonstrations at Lincoln Boyhood and elsewhere in the area. Bill Koch hired Vivian Burns to demonstrate her skills seasonally at Santa Claus Land (now Holiday World) using a second great wheel Bob purchased and rebuilt. The superintendent also gave demonstrations, including an eight—hour presentation at the 1965 Golden Rain Tree Festival in New Harmony, Indiana. When the Burns family transferred to Nez Perce in 1965, Koch sought their aid in finding another wheel to continue the demonstrations at Santa Claus. [7]

In two short years, Bob Burns made great strides in developing the park's interpretive program and building public support for the National Park Service. His successor, Al Banton, built on the foundation Burns had laid. Adding some programs and eliminating others, Banton's program was different, but still focused on Lincoln's boyhood years in Indiana.

Among the programs Banton eliminated were the weekly television broadcasts. Banton wanted to spend more time building the onsite interpretive program and felt he could not do both well, so he discontinued the weekly telecasts. [8]

A major addition to onsite interpretive program was the completion of a film, "Here I Grew Up." Narrated by Senator Everett McKinley Dirksen of Illinois, the film interprets young Abraham Lincoln's days in southern Indiana. Filmed at New Salem, Illinois, it featured several local residents and park staff members and their families, who volunteered to participate. [9] "Here I Grew Up" debuted in Washington, D. C., in a Lincoln Day celebration on February 11, 1968, [10] and is still shown daily in the visitor center at Lincoln Boyhood.

The film's longevity is more interesting because Superintendent Banton tried to scuttle it before it was released in 1968. Shortly before its completion, Banton saw a light—and—sound presentation at another park, and felt it was a fresher, more modern interpretive show. He hoped to replace the unveiled film with a similar light—and—sound show for Lincoln Boyhood. Banton failed to stop the film's release, however, [11] and although somewhat dated, visitors continue to enjoy its simple story.

Banton's most popular impact on Lincoln Boyhood's interpretive program was the establishment of the living historical farm. Construction began March 5, 1968, and the major structures were in place two months later. Banton had some seasonals on duty that summer, all men. They cleared fields, planted crops, and split rails and firewood. Perhaps the biggest problem for the first summer's laborers was locating appropriate historic tools to use in the work. [12]

The farm was still under construction when Democratic Senator Robert F. Kennedy and his family visited the park while in the area during the 1968 presidential primary campaign. Kennedy ate food prepared by the farmers and placed a bouquet on Mrs. Lincoln's grave. [13] A few weeks later, Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles.

In 1969, the living historical farm opened for its first full interpretive season. (See Figure 9—1.) Banton hired several seasonal interpreters to work solely at the farm. Most came with special skills; others learned while on the job from the experts such as Mary Conen. A few came with some skills, like knitting, and learned others, such as spinning. [14] Each kept a daily log of the tasks performed at the farm. During that first summer, Banton had at least one man and one woman doing costumed interpretation every day. The men worked in the fields, cared for the animals, and demonstrated rail splitting, wood—chopping, shingle—riving, horseback riding, smoking meats, and (beginning in 1970) firing the flintlock rifle. The women gave demonstrations in candlemaking, soapmaking, herb—gathering, dye—making, gardening, and spinning. [15]

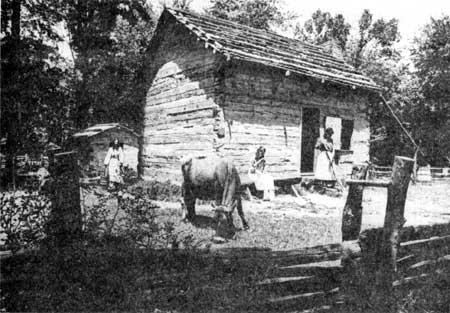

|

| Figure 9-1: Interpreters Ruthanne Heriot, Judy Schum, and Mary Carlisle working at the living historical farm, 1973. National Park Service photograph files, negative no. 3, photographed by Richard Frear. |

In 1970, added funds permitted an increase in the interpretive staff, and the living, history season stretched from April through October. Visitors loved the program. To preserve the demonstrations done by some of the older crafters, the park obtained a video tape recorder and taped the demonstrations. The tapes were used to teach the skills to subsequent interpreters, and for shows during the off—season. [16] Although the visitor center closed on Mondays and Tuesdays from November 1, 1971 through April 1, 1972, the farm remained open year round. Winter farm life became part of Lincoln Boyhood's interpretive story. [17]

In spite of the living historical farm's popularity, Superintendent Banton recognized its shortcomings. Banton fully understood that the farm could not recreate the survival atmosphere which must have surrounded the struggling Lincoln farm, particularly during the first few years. He knew the living history demonstrations lacked the context of the Pigeon Creek community. He knew the park could utilize only a small portion of the land once farmed by the Lincoln family. He recognized that modern visitors often failed to realize that historically, the cabin was used primarily for sleeping, eating, and a few other activities. Almost everything else was done outdoors. Nevertheless, Banton resolved to do the best interpretation of an early—nineteenth century southern Indiana farm possible. [18] He determined to use historical farming methods when visitors were present, but to save time and money by utilizing modern techniques when they were not. [19] He tried to bring the Indiana Lincoln story alive.

Among Banton's favorite ways to do that was reaching children. The Service's initiation of a National Environmental Education Development (NEED) program in 1968 provided a wonderful opportunity to do just that. In cooperation with Educational Consulting Service Director Mario Menesini, the National Park Service developed a program to encourage environmental awareness in school and park interpretive programs; materials were developed for use in schools, and many parks established National Environmental Study Areas for children's onsite learning. Banton initiated an environmental awareness program at Lincoln Boyhood that same year; Director George Hartzog announced the program at a dinner held in the Nancy Hanks Lincoln hall. As discussed in the chapter on development, Banton returned a portion of the historic Lincoln farm never used for crop production to its early—nineteenth century natural state. In cooperation with the Indiana Department of Natural Resources (formerly the Department of Conservation) and Lincoln State Park, Banton then started a program in which schoolchildren camped in the state park, and participated in activities there and at the living historical farm. [20]

Under the National Environmental Education Development program, students in fourth through sixth grades churned butter, planted corn, split shakes, carved wood, learned to spin, and made gravestone rubbings. [21] In 1971, three schools from Rockport and Muncie, Indiana, signed up for the program, and the Dale Girl Scouts helped with the spring planting. The following year, the camp served four schools, including one from Evansville, Indiana. [22]

Superintendent Bill Riddle cultivated the NEED program, and in 1974 the camp served five schools, or approximately 400 children grades four through six. [23] The number of schools involved in the NEED program continued throughout the Seventies.

Undoubtedly, the living historical farm was, from its inception, an extremely popular program. It still is. It must be noted, however, that the farm interpretive program is not without controversy. Some within the National Park Service are concerned that the farm places emphasis on "material aspects of farm life rather than the subject that the area was intended to commemorate." [24] Proponents of the farm argue that it is the farm which brings many visitors to the national memorial, where they then discover the significance of the park. Although the debate may continue indefinitely, so likely will the program, as long as it retains the support of Lincoln Boyhood's superintendents. To date, Superintendents Banton, Riddle, Beach, and Hellmers all enthusiastically embraced the living historical farm.

Some changes in the living history program occurred over time. Banton originally hired interpreters for the farm or the visitor center, and rarely used them for other than their intended duties. By 1969, however, superintendents allowed some crossover of duties, and actively scheduled interpreters at alternating jobs to give them a fuller understanding of the entire memorial. [25] Over the years, too, the interpretive demonstrations at the farm have become more refined and better organized. The farm is undeniably a vital part of the park's interpretive program.

Other interpretive projects also grew and developed. Park staff gave offsite demonstrations at various schools and for groups like the Lincoln Club of Southern Indiana. Various clubs used the Nancy Hanks Lincoln hall for their regular meetings. Sunday services and occasional weddings took place in the Abraham Lincoln hall (sometimes called the chapel).

In 1976, Superintendent Riddle, Park Technician Gerald (Jerry) Sanders, and others participated in weekly radio shows called "Along the Lincoln Trail" on Jasper, Indiana, station WITZ. Riddle also joined Lincoln State Park Superintendent Bill Carlisle and Lincoln Boyhood Park Technician Mary Carlisle on an Indianapolis television show, and an Evansville station did a program on the living historical farm. [26]

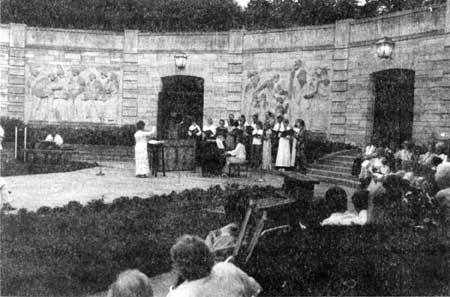

To celebrate the bicentennial of the nation's independence, Lincoln Boyhood initiated a summer film festival in 1976 [27] and hosted a special play commemorating the bicentennial. Franklin S. Roberts Associates, Inc., of Philadelphia toured the nation with a special outdoor program called "We've Come Back for a Little Look Around." Jointly sponsored by Franklin S. Roberts Associates and Temple University, the six actors portrayed some of our founding fathers who returned to take a look at the United States after its first two centuries. (See Figure 9—2.) The park held three showings on July 24, 1975; attendance at the shows totalled more than 600 visitors. [28] The park also staffed bicentennial celebration booths at the Indiana State Fair and the Spencer County Fair in 1975. [29]

|

| Figure 9-2: A special bicentennial program, "We've Come Back for a Little Look Around," was featured in the courtyard in front of the visitor center on July 24, 1976. Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial photograph files, negative no. 551, photographer unknown. |

Riddle's successor, Warren D. Beach, continued to improve the authenticity of the farm interpretation, and expanded off—site visits to schools, nursing homes, and elsewhere. [30] Over the 1980 Memorial Day holiday, Beach ran three films based on Carl Sandburg's biography of Lincoln and starring Hal Holbrook. On the Fourth of July holiday weekend, Lincoln Boyhood sponsored another film festival featuring the full series of films based on Sandburg's biography." [31] The series was well—received, and Beach repeated the showings on the Labor Day weekend. Labor Day celebrations in 1980 also included a candlelit walk from the visitor center to the gravesite and on to the farm. [32] Lincoln Boyhood held another film festival on October 4—5, 1981. This time, they showed "A New Birth of Freedom," a biographical sketch filmed at related National Park Service sites, and "Lincoln: The Kentucky Years." [33]

The October 1981 festival coincided with Superintendent Norman Hellmers' arrival at Lincoln Boyhood. Apparently Hellmers liked the public's response, for film festivals continued to be special features of Lincoln Boyhood's interpretive program. In 1982, Hellmers showed "The Assassination of Lincoln" on Memorial Day weekend [34] and repeated "New Birth of Freedom" over the Fourth of July. [35] The following year Lincoln Boyhood ran films intermittently throughout the summer. [36]

Hellmers introduced other special programs in 1983. An Arbor Day program featured songs, poems, and talks about trees. [37] There was a special touch—and—feel exhibit in the visitor center May 15—21. [38] June 19—25, Lincoln Boyhood sponsored "Mary Conen's Pioneer Kids Corner" for which children were invited to dress up like pioneers and bring a camera to have their pictures taken at the farm. In July and August, three—year—old horses Babe and Maude and colt Lottie demonstrated "Lincoln's Horsepower" to visitors. [39] Park Technician Jerry Sanders' "Abraham Lincoln Fact Book and Teacher's Guide," published by Eastern National Park & Monument Association (ENP&MA)* in 1982, became a standard sales item in the visitor center. [40] Sanders' publication drew national attention when it was featured in the ENP&MA newsletter in the spring of 1983. [41]

*The Association uses the ampersand symbol (&) rather than spelling out the work "and" in their name, and includes the ampersand in their acronym.

Affiliation with the Eastern National Park & Monument Association has proved a great boon to Lincoln Boyhood's interpretive program since the park's inception. Membership allows park areas to purchase sales items (books, postcards, and slides) on consignment or at wholesale costs, then resell them to visitors for a profit. The Association also provides "grants" for small research projects, and helps buy equipment for interpretive programs. At Lincoln Boyhood, ENP&MA even purchased livestock for the living historical farm. In recent years, ENP&MA returned a "percentage donation" of funds to each member park based on that park's sales for the previous year. These funds are used for a variety of interpretive programs at Lincoln Boyhood, including the printing of free brochures and similar materials. The quantity of sales generated by Lincoln Boyhood made it possible for the park to hire sales personnel paid with Eastern funds. For several years, one position was thus funded; now the park hires two salespersons each year with ENP&MA funds.

The Eastern coordinator keeps books for the operation and places orders. At Lincoln Boyhood, the coordinator traditionally has been the historian or park technician; the exception was Superintendent Al Banton, who chose to do the coordinator's duties himself. [42]

Lincoln Boyhood's interpretive operation has benefitted from other programs as well. A Christian Ministry in the National Parks (ACMNP) is a national organization formed in 1966. The program recruits ministry students to work in areas where church services may not be available locally. The student minister gives interdenominational services on Sundays and is usually employed elsewhere in the park or nearby community during the summer season. Lincoln Boyhood has frequently utilized the program to provide Protestant worship services during the summer season; Catholic services were provided by priests from the St. Meinrad Archabbey. Through a cooperative agreement with Lincoln State Park, the priest and student minister gave services in both places each Sunday. Generally, the ACMNP students worked seasonally at Lincoln Boyhood as either interpreters or on the maintenance staff, although some worked elsewhere in the Spencer County area. Participation in ACMNP has benefitted both the parks and their visitors. [43] Appendix E contains a list of ACMNP ministers in the Lincoln City area over the twenty years since the program's inception.

Lincoln Boyhood's longstanding relationship with the Lincoln Club of Southern Indiana has also benefitted the memorial's interpretive programs.* organized in the Gentryville, Indiana, home of Mrs. Abner Crews, the Club became state and nationally federated that same year through the efforts of Mrs. Oscar Brigins and Mrs. Benson J. Woods. The club's purpose is to gather information about Lincoln, to preserve and extend Lincoln's heritage in southern Indiana, and to improve the historic Lincoln community. [44]

*In fact, the Lincoln Club of Southern Indiana was a friend to Lincoln Boyhood before the park existed. The club actively campaigned for the park's authorization. In recognition of their efforts, the Indiana Federation of Women's Clubs granted the Lincoln Club the first place award for community improvement in 1963.

Over the years, Lincoln Boyhood profited from several Lincoln Club activities. In the 1960s, the Lincoln Club of Southern Indiana sponsored a statewide campaign to acquire books on Lincoln and other subjects for the park library. The club donated some 500 volumes in the Sixties. Further, the Lincoln Club has worked with the National Park Service to sponsor Lincoln Day activities at the national memorial since the park's inception. The programs traditionally feature a speaker in the Abraham Lincoln hall followed by a gravesite service presented by a Lincoln Club member or community member descended from Spencer County's pioneer families. Lincoln Club members frequently serve as volunteers in the park's interpretive and resources management programs. [45]

In 1973, the Lincoln Club of Southern Indiana began promoting an outdoor drama to present Lincoln's boyhood story to the public. The Lincoln Boyhood Drama Association (LBDA) was formed in 1977, and Mrs. Freda Schroder of the Lincoln Club was the association's first president. The Lincoln Club president continues to hold a seat on the LBDA board of directors. Lincoln Boyhood's superintendent also holds an ex—officio seat on the board. Almost all of the Lincoln Club's fundraising activities since 1977 have served to raise funds for the Lincoln Boyhood Drama Association. [46]

The Lincoln Boyhood Drama Association formed for the purpose of telling:

. . . the story of Abraham Lincoln's boyhood years, and at the same time, to convey the meaning of these events, both to the remainder of Lincoln's life as well as to the larger, long—term view of American history. [47]

The Association solicited memberships at $25 each, and raised the funds to hire playwright Billy Edd Wheeler to prepare a play focusing on young Lincoln's qualities, on the factors that influenced him, and on correcting some misconceptions concerning the Lincoln family's financial status, Abraham's parents, and their life in Indiana. [48]

Although the park does not have a formal relationship with the LBDA, Superintendent Norman Hellmers is on the Association's board of directors and has served on two committees. In a memorandum to Regional Director Charles Odegaard on April 23, 1985, Hellmers stated his intention to form an agreement between the memorial and the LBDA to review the script for historical accuracy, and to promote the play. [49] Hellmers anticipated the production could eventually increase visitation at Lincoln Boyhood by some 40—50,000 per year. [47]

In 1985, the State of Indiana appropriated $3.35 million for the construction of an amphitheater at Lincoln State Park. Construction was completed in June 1987. [50] The play, "Young Abe Lincoln," provided another major boon to Lincoln Boyhood's interpretive program beginning in the 1987 summer season.

The outdoor drama is a welcome complement to the variety of interpretive offerings at Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial. Each superintendent has made strong contributions to the park's interpretive program. The result is a well—rounded strategy for bringing the Lincoln story to the public.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

libo/adhi/adhi9.htm

Last Updated: 25-Jan-2003