|

Lincoln Boyhood

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER I:

Early Efforts to Memorialize Nancy Hanks Lincoln

When "milk sickness" ravaged the Pigeon Creek community in 1818, there was no church nor formal cemetery in the new settlement. Thomas and Betsy Sparrow, Nancy Hanks Lincoln's uncle and aunt, were among the first to die from the epidemic. A few days later, Nancy Hanks Lincoln died and was buried near the Sparrows on a knoll overlooking the Indiana home she dearly loved. As others in the community died, they were placed beside the Sparrows and Nancy Lincoln in the informal graveyard. Eight years later, in December 1825, the Pigeon Creek Primitive Baptist Church set aside some of its land one mile to the south of the graveyard for a formal cemetery. Coincidentally, Abraham's sister, Sarah, and her stillborn child were among the first buried in the church graveyard; Sarah Lincoln Grigsby died in childbirth in January 1828. [1]

Thomas Lincoln moved his family to Illinois two years later. The land changed ownership several times in the decades following the Lincolns' emigration, and the small graveyard on the privately owned land was neglected. Over the years, whatever "monuments" once marked the graves disappeared. Little note was made of the humble graves of ordinary pioneers who lost their lives settling the land. If not for her son's infamous assassination and subsequent memorialization, Nancy Hanks Lincoln's gravesite might have remained lost to posterity.

Until Abraham Lincoln became President, there were probably few who paid much heed to the Lincolns' fourteen years in southern Indiana. Thomas Lincoln's family was typical among pioneer families; Thomas was no richer nor poorer than most in the Pigeon Creek community. Although Thomas Lincoln's carpentry skills were known and respected throughout the community, the family did not stand out from their neighbors. Even Abraham Lincoln's election to the presidency in 1860 failed to draw visitors to the land where Abe grew up.

Lincoln's assassination changed the situation somewhat, as a smattering of curiosity seekers and true admirers of the president sought Lincoln's Indiana home and his mother's grave. In April 1865, some residents of the nearby town of Elizabeth (later Dale) went to the Lincoln farm area and posed for pictures taken in front of the 1830 cabin started by Thomas and Abraham Lincoln.* Two sepia prints of that showing Mr. [?] Kelsey; Mr. George Medcalf; Mr. [?] Sanders, the schoolteacher; Mrs. Clara Kelsey Ball; [Mrs.] Evelyn "Siss" Miller, and Mrs. [?] Kelsey seated before the cabin (see Figure 1—1); and one showing the men in the party pretending to split logs in front of the structure. [2] Artist John Rowbotham visited the farm in 1865, and commented that the grave was unmarked, but named several people in town who could direct visitors to it. Lincoln's Springfield, Illinois, law partner, William Herndon, visited the farmsite in September 1865 and talked with local residents about the Lincolns. [3] Rowbotham followed his visit with a drawing of the Lincoln cabin (Figure 1—2); Herndon wrote some observations on the Indiana homestead.

*Although Thomas and Abraham prepared logs and began construction on a new cabin, it was finished by subsequent residents after the Lincolns moved to Illinois. The Lincolns never resided in the later cabin.

|

| Figure 1-1: Photograph of Dale, Indiana, residents posing in front of the 1829 Cabin shortly after Lincoln's assassination, 1865. Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial photo files, negative no. 448, photographer unknown. |

|

| Figure 1-2: Copy of John Rowbothom's drawing of the Lincoln cabin as it appeared in 1865. Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial photo files, negative no. 446, phogotrapher unknown. |

Three years later, a Civil War veteran named William Q. Corbin visited the boyhood home of his former commander-in-chief. Corbin was disgusted with the unkempt appearance of the gravesite, and wrote a poem on the subject. His poem, published in the Rockport Journal in November 1868, was among the first known public account of the grave's condition.

On December 24, 1869, some Gentryville businessmen met to discuss erecting a suitable marker; in attendance were J. W. Wartman, Dr. M. E. Lawrence, T. P. Littlepage, James Hammond, J. W. Lamar, N. Grigsby, James Gentry, J. H. Houghland, and J. M. Grigsby. No results of this meeting are recorded, but the creation of "Mrs. Lincoln's Monument Fund Committee's" in Rockport in the early 1870s indicates the grave was still unmarked. The Rockport committee solicited funds, but received few. They dropped the project and disbanded. [6] In the meantime, Henry Lewis, John Shillito, Robert Mitchell, and Charles West, all of Cincinnati, bought a large parcel of land from James Gentry. Originally called Kercheval, the Cincinnati developers intended to use the property which encompassed Thomas Lincoln's farmstead to create a new town. Due to the efforts of Indiana Congressman James Hemenway, the town became known as Lincoln City in 1881. [7]

W. W. Webb ran an article in the June 2, 1874, Rockport Journal commenting on the poor condition of Nancy Hanks Lincoln's grave. [8] A month later, a meeting of "old settlers" was called to arrange for a marker, but again, no action was taken. [9] Thoroughly disgusted, Rockport businessman Joseph D. Armstrong erected a two-foot tall marker inscribed simply with the deceased's name, Nancy Hanks Lincoln. Some other Rockport businessmen may have contributed to the purchase. [10]

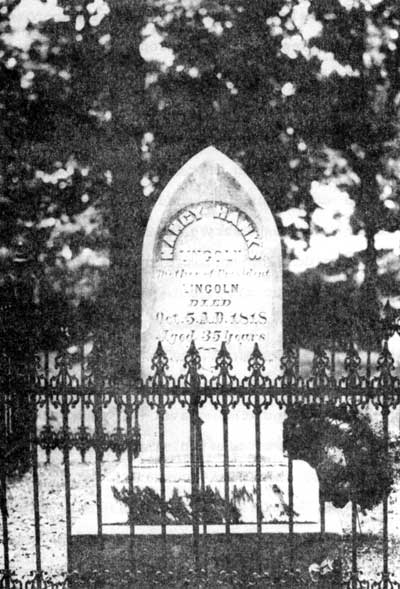

When a newspaper reporter sought the gravesite five years later, however, he found it unmarked, overgrown with vegetation, and almost inaccessible. The reporter's article deplored the gravesite's condition, and gained the attention of Peter E. Studebaker, second vice president of the Studebaker Company, Carriage Makers, of South Bend, Indiana. Studebaker contacted Rockport Postmaster L. S. Gilkey with instructions to buy the best tombstone available for $50.00 and have it anonymously placed on the gravesite. R. T. Kercheval contacted Henry Lewis, the trustee for the Cincinnati firm developing Lincoln City, and the firm donated the half-acre surrounding Mrs. Lincoln's grave to Spencer County. On November 27, 1879, when the tombstone was laid, Civil War Major General John Veatch of Rockport collected another $50.00 (one dollar from each of 50 area residents) to erect a fence around the grave. [11] (See Figure 1—3.) The following June, a commission including Joseph Armstrong, Nathaniel Grigsby, R. T. Kercheval, James C. Veatch, Joseph Gentry, John W. Lamar, L. S. Gilkey, I. L. Milner, Henry C. Branham, and David Turnham was formed to care for the gravesite. [12] Finally, it seemed, the grave would receive proper care.

|

| Figure 1-3: The Studebaker gravestone and ornamental fence erected at the Nancy Hanks Lincoln gravesite in 1879. Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial photo files, negative no. 6, photographer unknown. |

For a time, it did. Then in the late 1890s, reports of the gravesite's unkempt appearance circulated again. Studebaker believed the reports were exaggerated, but decided to have one of his employees investigate. [13] Meanwhile, Benjamin B. Dale, a Cincinnati attorney hired by the former owners of the gravesite property, visited the site and was shocked by the lack of maintenance. Spencer County citizens asked Senator Charles W. Fairbanks of Indiana to seek Federal funds to provide for the maintenance of the gravesite, but Governor James E. Mount objected, saying care of the gravesite was a state responsibility. There was some talk of moving Mrs. Lincoln's body to Indianapolis, but Spencer County residents' objections ended that proposal. On June 30, 1897, Governor Mount called a meeting of several state patriotic agencies which resulted in the formation of the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial Association, for the purposes of soliciting funds for maintenance of the gravesite and promoting an Indiana memorial to the Lincolns. Unfortunately, after three years, the Memorial Association had collected only $56.52. [14]

That situation improved in 1900, when United States Senator J. A. Hemenway donated $100 to the fund and Robert Todd Lincoln gave $1000 for the care of his grandmother's grave. This stimulated the appropriation of $800 to enable the commissioners of Spencer County to purchase sixteen acres surrounding the gravesite from Robert L. Ferguson and his wife, Carrie. A few months later, Spencer County transferred the deed to the Indiana Lincoln Memorial Association, and charged the Association with maintenance of the gravesite. The property would revert to the county if not properly attended. [15]

In 1902, following the completion of an elaborate monument at President Lincoln's grave in Springfield, Illinois, J. S. Culver resculpted a discarded stone from Abraham's original monument and vault as a monument to Nancy Hanks Lincoln. Governor Winfield T. Durbin, president of the Memorial Association, accepted the massive stone and had it placed in front of the Studebaker marker. (See Figure 1—4.) The so-called "Culver stone" was dedicated in a graveside ceremony on October 1, 1902. [16]

|

| Figure 1-4: The "lions and eagles" gate, circa 1929. Department of Conservation photo, Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial Papers, Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Indianapolis, Indiana. |

Once again, it seemed the gravesite would receive proper care. Once again, it was not so. By 1906, the small park was in a deplorable state of disrepair, and Governor J. Frank Hanley called on the organization to explain its inactivity. Hanley's attempt to revitalize the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial Association was unsuccessful. [17] The Spencer County commissioners deferred their option to repossess the acreage they had donated to the Association until the state legislature reconvened the following spring. In 1907, the Indiana assembly dissolved the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial Association, transferred its funds,* records, and property to a newly established Board of Commissioners, and appropriated $5000 for the erection of an ornamental fence around Mrs. Lincoln's grave and other improvements. The Board consisted of the Secretary of State on the Board of Forestry and two individuals appointed by the governor, at least one of whom had to be from Spencer County. [18] The Board of Commissioners hired landscape architect J. C. Meyenburg of Tell City, Indiana, to prepare design documents for site improvements. In 1909, utilizing those plans, the state cleared the sixteen-and-one-half-acre park of dead trees; erected an iron fence around the property, including an elaborate entry gate, and built a macadamized road from the highway to the gravesite. The entryway featured life-size lions at the highway entrance, with eagles perched on columns south of the lions, closer to the gravesite. (See Figure 1—4.) Large stone urns dotted the roadway to the cemetery. [19]

*The Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial Association transferred $925.37 of the total $1155.52 it collected to the Board of Commissioners. The association had spent $231.15 to drill a well. Notes on Hanley meeting, Box 1, Folder 1.

Indiana celebrated its centennial in December 1916, and Spencer County's hundredth anniversary was 1918.** Among the centennial programs was a thrust to identify locations important to the state's history. In 1917, John J. Brown and John Chewning, members of Spencer County's centennial commission, formed a committee to obtain the assistance of older residents of the county in determining the exact location of Thomas Lincoln's cabin. Twenty such residents assembled on the historic Lincoln property on March 12. The site was identified by Davis Enlow, Joseph Gentry, and "the Lamars." This group pointed to the site they believed to be correct, and the first shovelful of dirt revealed cobbles and crockery. A marker was erected on the site on April 28, 1917, stating: "Spencer County Memorial to Abraham Lincoln, Who Lived on this Spot from 1816-1830." [20]

**When Thomas Lincoln staked his claim near Pigeon Creek, the land was in Warrick County. The county lines were redrawn in 1818.

Shortly after the cabin site was identified, interest in the historic Lincoln property escalated. Historian William Barton made an editorial plea for the state to assume control of the Thomas Lincoln farmstead in 1921, [21] and Claude Bowers built on the idea with his editorial, "Where Indiana Fails," the following year. [22] The failure of Indiana to memorialize Abraham Lincoln became a major theme of subsequent campaigns to erect a state memorial honoring the Lincolns.

Colonel Richard Lieber, director of the Indiana Department of Conservation, was sympathetic to this issue. The state park movement was very strong in the 1920s, and Lieber hoped to develop a constellation of scenically beautiful and historically significant parks. [23] A Lincoln memorial fit perfectly into his plan. Lieber first addressed the issue publicly in a 1922 speech before the Ft. Wayne First Presbyterian Church Men's Club. [24] His support proved a vital factor in the eventual establishment of the Nancy Hanks Lincoln State Memorial and Lincoln State park.

In 1924, southern Indiana residents formed the Boonville Press Club, which kept the memory of Nancy Hanks Lincoln alive by having well-publicized picnics at the park annually. In its first year, the club had just a handful of members; a decade later, membership was approximately 16,000. The club claims its publicity was instrumental in the establishment of the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial. [25]

In response to the increased attention to an Indiana Lincoln memorial, the state assembly passed an act creating the Lincoln Memorial Commission on March 3, 1923. The commission, which replaced former governor Hanley's 1907 Board of Commissioners, comprised nine members appointed by the governor for three-year terms.* All properties previously owned by and powers once granted to the disbanded Board of Commissioners were transferred to the new commission. Further, the act authorized the Lincoln Memorial Commission to purchase land and build structures, as needed, and "to prepare and execute plans for erecting a suitable memorial to the memory of Abraham Lincoln at or near his residence in the state." [26] Responsibility for the care of the gravesite was transferred to the Indiana Department of Conservation. [27]

*Applications for appointments to the commission are located in the park files. See Park files, Lincoln Related Organizations: Commissioners of Nancy Hanks Lincoln Burial Ground, 1907-1925, Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, Lincoln City, Indiana.

The commission's first attempt to acquire land for the state, the forty-six-acre Patmore farm near Lincoln City, raised a sticky issue: The sixteen-and-one-half-acre park formerly managed by the Board of Commissioners was not owned by the state. The land had reverted to Spencer County in 1907 when the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial Association failed to maintain the gravesite properly. The Fergusons filled out a form deeding the land to the state in 1907, but it was no longer theirs to give; it belonged to the county. Apparently no one realized the state had been managing county-owned land for almost two decades. When the problem came to light in 1925, Spencer County quickly but quietly transferred ownership to the state, and purchase of the Patmore property was completed. The Lincoln Memorial Commission then operated a 60-acre park. [28]

Department of Conservation Director Richard Lieber accepted responsibility for the care of the the Nancy Hanks Lincoln gravesite enthusiastically. Lieber met informally with Marcus Sonntag and Will Hays on July 19, 1926, to discuss the idea of a Lincoln "shrine." The three went to Governor Ed Jackson that evening to seek support for the concept. Jackson did not disappoint them. [29] The following December, Jackson invited 125 Indianans to form the Indiana Lincoln Union (ILU) so "that the people of [the] state in mighty unison [could] rear a national shrine" honoring the Lincolns. [30]

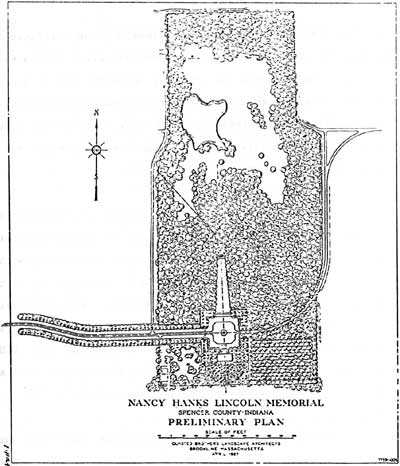

Within days, C. G. Sauer requested a proposal for the memorial park's development from the noted landscape architect, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. [31] On January 24, 1927, the state hired the Olmsted Brothers firm to prepare preliminary designs for the memorial. Olmsted did not delegate the project to one of his subordinates; instead, he visited Spencer County the following March, then returned to his office in Brookline, Massachusetts, to commence designing.

When Olmsted made his initial visit to Lincoln City in March 1927, he was pleased to discover the countryside had not been altered irretrievably from the land where young Abraham Lincoln lived. There were, of course, elements which intruded on the historic scene. C. G. Sauer had warned Olmsted of these when he first contacted the landscape architect the previous December. [32] There were several buildings on the site of the Thomas Lincoln farm. A railroad crossed the land between the cabin site and Nancy Lincoln's grave. A highway traversed the area, too, and a large ornamental iron gate marked this current (i.e., 1927) entrance to the gravesite. Exotic vegetation had been introduced, compromising the historic southern Indiana forest. Still, Olmsted was confident in Sauer's prediction that these intrusions could be removed and the "sacred land" could be restored to its appearance of one century before. [33]

Olmsted's preliminary sketches were accompanied by voluminous notes explaining his concept of the memorial, a monument of strength and simplicity, sentiment and reason. He wanted the memorial to remain simple, so as not to overwhelm the "familiar associations" of the area with the Lincolns. On the other hand, Olmsted was not satisfied to restore the area to its natural condition. Olmsted realized some sort of monumental expression was needed. That "frankly and obviously monumental" landscape was his proposed allee, extending from the plaza toward the gravesite. (See Figure 1—5.) Olmsted returned to Lincoln City to present his preliminary concept on May 7, 1927. The delegation embraced his ideas enthusiastically. [34]

|

| Figure 1-5: Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. Preliminary Plan, Nancy Hanks Lincoln Memorial, Spencer County, Indiana, April 1927. Frederick Law Olmsted Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. |

The May 7 meeting was also the occasion of the ILU's first splashy attention-getting event. It was artfully scheduled for just before Mother's Day, and began at 11:00 a.m. when the ILU met with its guests in an open field south of the gravesite. As they gathered, a plane flew overhead and dropped a message which the governor read at 11:15 a.m., after Mrs. Anne Studebaker Carlisle placed a wreath on Nancy Hanks Lincoln's grave. Governor Jackson's speech was followed by an address in which Colonel Lieber reminded those present (including the press) that Olmsted's plans were secret. (This statement may have been made to encourage, rather than discourage, press interest in the story.) Olmsted then presented his design to the ILU's executive committee, and, following a 2:00 p.m. luncheon in Dale, the group dispersed. [35]

Soon thereafter, the Indiana Lincoln Union initiated its campaign to raise funds for the memorial park. Theirs was a three-part plan aimed at raising support via a massive newspaper advertisement and publicity campaign; enlistment of schoolchildren (and their parents) by way of a speech contest; and solicitation of funds by seeking pledges and by door-to-door canvassing.

Frank C. Ball of Muncie was named state chairman for the campaign. Marcus Sonntag of Evansville chaired fund-raising activities in the southernmost portion of the state; Arthur F. Hall and Henry Leslie were Sonntag's counterparts in the northern and central regions, respectively. Anne Studebaker Carlisle chaired the school contest and promotions. The closing statement on a handbill announcing the ILU's committees stated the organization's philosophy: "Indiana Should Do It; Indiana Can Do It; Indiana Will Do It." [36]

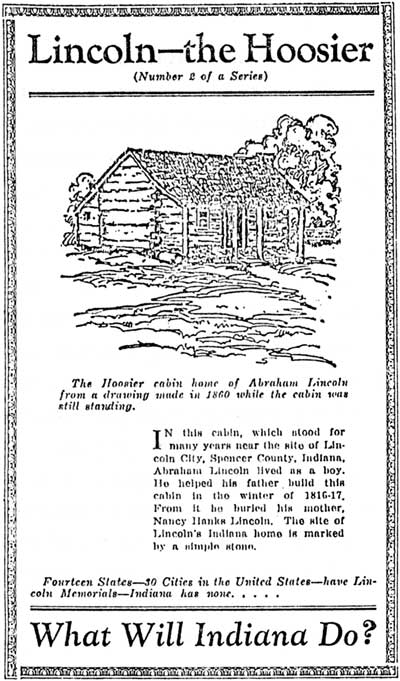

The ILU hired George E. Lundy of the New York advertising firm Hedrick, Marts, and Lundy, Inc. to promote its cause. [37] Lundy deluged Indiana newspapers of all sizes with advertisements. [38] The campaign focused on a series of six ads to be featured on consecutive days. (See Figure 1—6.) Lundy also enclosed news spots to be featured as space was available over a two-week period. The ILU later ran two additional announcements, measuring five columns in width by seventeen inches. Each advertisement concluded with the theme: "Fourteen states;—30 Cities in the United States—have Lincoln Memorials—Indiana has none .... What Will Indiana Do?" [39]

|

| Figure 1-6: One of the six advertisements designed by Hedrick, Marts, and Lundy, Inc. to promote an Indiana Lincoln Memorial. Indiana Lincoln Union Papers, Indiana State Archives, Indianapolis, Indiana. |

The Indiana Lincoln Union supplemented the advertisement campaign with a massive mailing program. The ILU sent more than 200,000 letters to Indiana citizens and institutions soliciting support for the memorial. [40] Among the organizations targeted were a variety of travel-oriented groups, such as the Hoosier State Automobile Association and the Good Roads Board. [41] The letterhead used for these mailings proudly boasted: "Lincoln was a Hoosier." [42] In addition, the ILU published a sixteen-page booklet in 1927 entitled "Lincoln Memorials." The document described other memorials to Abraham Lincoln, and showed Frederick Law Olmsted's preliminary design for the memorial, as well as a structure designed by architect Thomas Hibben. [43] The advertisements, mailings, and pamphlets saturated the state with the memorial concept.

Further support for the memorial was engendered via an oratory contest. The ILU held competitions in each of the three districts, and awarded prizes to the boy and girl in each district who most convincingly stated the need for an Indiana Lincoln memorial. The city of Gary donated plaques for the district winners, local businesses gave clothing, and each district winner received a gold watch. The contest culminated in a tournament featuring the six district winners; the state champions each won a trip to the nation's capital. [44]

A vital aspect of the Indiana Lincoln Union's campaign was fund-raising. The ILU solicited funds based on a quota; each county was expected to contribute 0.00028 of its December 1926 net value. [45] Canvassers sought funds door-to-door. Those making pledges were expected to pay one-fifth of the amount promised every six months over a two-and-one-half year period. [46] ILU Treasurer Thomas Taggart sent reminders if payments were late. [47]

Unfortunately, the onset of this nation's greatest economic depression, which had a firm grip on agricultural states by the late 1920s, made it impossible for many to meet their pledges. When the ILU sent one gentleman a letter stating, "[We believed] you were sincere in your voluntary pledge to this enterprise, and therefore proceeded with the execution of the memorial plans[,]" the gentleman responded, somewhat bitterly:

I was sincere [emphasis his] when I made this pledge. Though we were promised this unprecedented wave of prosperity would continue, sometimes I did not believe it—hence the pledge. But just as soon as this period of prosperity abates—I will evoke my remittance.[sic]" [48]

Many pledges made during a time of prosperity could not be met when the economy turned sour. Nevertheless, the ILU's fundraising campaign was phenomenally successful.

While seeking public support for the memorial, the Indiana Lincoln Union worked toward meeting the needs of the proposed park. The ILU recognized the need for more information on the Lincolns' years in Indiana, and in 1928 the Union appointed the Historical Research and Reference Committee to conduct research into the subject. [49] The appointment of the Southwestern Indiana Historical Society's Bess V. Ehrmann as chair of the committee raised some controversy. Apparently Dr Louis Warren, an expert on the subject of the Lincolns in Indiana, discredited the Southwestern Indiana Historical Society as a group of "unreliable . . . interpreters." [50] An irate letter from John E. Iglehart to ILU Executive Secretary Paul V. Brown complained about Warren's statement; Brown's response spoke of the Union's high hopes for the research committee, but diplomatically avoided the Warren issue. [51]

All of this activity represented continuing progress in the establishment of an Indiana Lincoln memorial. Heartened by popular enthusiasm for the concept, and based on the pledges of financial support made, the state purchased several additional acres in the Lincoln City area in the late 1920s.

The park project received a major boost in 1929, when Frank C. Ball of Muncie, Indiana, purchased approximately twenty-nine acres* of the historic Thomas Lincoln farm for $32,000, then donated the land to the state. On June 6, 1929, Governor Harry G. Leslie gathered many of the state's leading dignitaries to a ceremony at which he formally accepted Ball's donation. In keeping with the Indiana Lincoln Union's policy of recognizing such generous donations, the ceremony received full press coverage. Stories accompanied by photographs of Ball handing the deed to Leslie appeared in newspapers throughout the state. [52] With Ball's donation, the Indiana Lincoln Memorial was well on its way.

*Correspondence refers to twenty-nine or thirty acres donated by Ball, but a 1937 report prepared by Virgil M. Simmons, then Director of the Department of Conservation, cites the Ball donation as totalling 22.5 acres. See Simmons, Cost and Acreage Report, May 1937. Park files, Land Records, State Land Acquisition, 1920s, Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, Lincoln City, Indiana.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

libo/adhi/adhi1.htm

Last Updated: 25-Jan-2003