Survey of

Historic Sites and Buildings

THE passage of some 170 years and the emergence of an industrial technological America have wrought vast changes along the route of Lewis and Clark—changes they could never possibly have envisioned. Although not even the most enthusiastic preservationist would expect the land to remain totally unchanged, the scarcity of sites associated with the expedition is astonishing.

That the rampaging Missouri River Lewis and Clark knew would be tamed, that many of their campsites would be submerged, that most of the native trails they traversed would disappear from the plains and mountains, that the majestic Great Falls of the Missouri would be reduced to a trickle—all would seem unbelievable to the two captains. That the vast herds of buffalo, elk, and antelope, as well as the numerous grizzly, would be all but extinct, except where sanctuary exists, would seem equally as preposterous. The disappearance of the great falls of the Columbia would be beyond comprehension.

Yet, all this has come to pass—and more. As a matter of fact, were Lewis and Clark alive today, they would be unable to recognize many parts of their route and the raw wilderness they encountered. Where once were swirling and dangerous rapids, in many places today water skiers glide over glassy waters; where once salmon and other fish swarmed in the crystal-clear rivers or wildlife thrived along their banks, are often polluted streams and semibarren land; where once powerful currents lashed at riverbanks, are frequently huge levees; where once were dense forests and fertile soil, are sometimes scarred, depleted, and eroded areas.

|

| Official emblem of the Lewis and Clark Trail Commission. This symbol, slightly modified, highlights the trail throughout the West. (Bureau of Outdoor Recreation.) |

THE greatest alteration to the Lewis and Clark route—primarily a watercourse along the Missouri and Columbia River drainages—has been made by the dams constructed by the Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, and private power companies. In the process of remaking the river systems, they have provided industry with energy, brought payrolls, furnished irrigation water and electricity to farmers and ranchers, controlled floods and erosion, and enhanced recreational facilities. Regrettably, losses have occurred from the archeological and historical points of view.

Only relatively short stretches of the Missouri and the Columbia remain in an unharnessed state, and in other places the worst bends have been sliced away to improve navigation and reduce erosion. The Middle Missouri has been transformed. Beginning at a point just above Yankton, on the South Dakota-Nebraska border, six Corps of Engineers dams have converted the once-rugged stream into a string of placid lakes—sometimes known as the "Great Lakes of the Missouri." Extending from Nebraska across both Dakotas and into Montana, in order upriver these dams (reservoirs in parentheses) are: Gavins Point (Lewis and Clark Lake), Fort Randall (Lake Francis Case), Big Bend (Lake Sharpe), Oahe (Oahe Reservoir), Garrison (Lake Sakakawea), and Fort Peck (Fort Peck Reservoir).

The tail waters of each of these reservoirs practically laps at the face of the next. They have impounded thousands of square miles of water, inundated thousands of acres of river valley, and obliterated many prehistoric and historic places—not only those related to the Lewis and Clark Expedition, but also those of Indian villages and hunting grounds, fur trading posts, missions, battlefields, and emigrant routes.

Oahe Reservoir covers the Corson County, S. Dak., sites of the three Arikara villages that the expedition visited in 1804 and 1806 and that of Fort Manuel, the apparent location of Sacagawea's death and possibly that of her grave. Point of Reunion (Mountrail County), N. Dak., where the two Lewis and Clark elements reunited on the return trip after separating at Travelers Rest, Mont., lies beneath Lake Sakakawea.

Fortunately, just before the dam construction occurred, in 1946, the Missouri Basin Project, part of the River Basin Surveys of the Inter-Agency Archeological Salvage Program, began to investigate sites scheduled for inundation by the Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation. Within rigid budgetary and time limitations and using both governmental and private funds, the National Park Service, Smithsonian Institution, and various universities and historical societies surveyed, investigated, excavated, and researched scores of paleontological, prehistoric, and historic sites. Photographs were taken, artifacts collected, data recorded, and many of the results published.

Farther upriver, at the Great Falls of the Missouri extensive hydroelectric development has been carried out by the Montana Power Company along a 9-mile stretch of the Missouri near the city of Great Falls. Five dams utilize the power generated by the several falls.

Beginning another 84 miles upstream are the Montana Power Company's Holter (Holter Lake) and Hauser (Hauser Lake and Lake Helena) Dams, as well as the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation's Canyon Ferry Dam and Reservoir, which extends as far as Townsend, Mont. The river is submerged at one place in the area to a depth of nearly 100 feet. Included is the spectacular gash in the 1,200-foot granite heights known to Lewis and Clark as the "Gates of the Rocky Mountains." But the sheer rock walls still tower above the gorge so overpoweringly that the only perceptible difference is the still water that has replaced the once-powerful current.

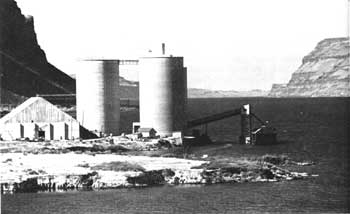

|

| Modern America has left its mark along the Lewis and Clark route. Pictured here are grain elevators at Wallula Gap, Wash. Lewis and Clark met the Walla Walla Indians in this area. (Bureau of Outdoor Recreation (Blair, 1964).) |

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation's Clark Canyon Dam (Hap Hawkins Lake), on the Upper Beaverhead River, has eradicated a major Lewis and Clark site, Camp Fortunate (Beaverhead County), Mont. It was the scene of many key events, especially on the westbound journey.

From Clarkston, Wash., and Lewiston, Idaho, at the mouth of the Clearwater, a chain of reservoirs on the Snake and Columbia reaches 320 river miles to Bonneville Dam, only 145 miles from the Pacific, and have immeasurably changed the streams. Dams on the Snake include (east to west) Little Goose, Lower Monumental, and Ice Harbor, all operated by the Corps of Engineers.

Various Corps of Engineer dams are located on the Lower Columbia: McNary, John Day, The Dalles, and Bonneville. The latter two have inundated Celilo Falls, The Dalles (including the Short Narrows), Long Narrows of the Lower Dalles, and the Cascades (Grand Rapids)—a 55-mile stretch of treacherous falls, rapids, narrows, and chutes that were a severe problem to the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Now they all lie quiet and unseen beneath huge artificial lakes; churning white water and leaping salmon can no longer be seen.

|

| Celilo Falls at some unknown date prior to construction of The Dalles Dam, which covered the great falls. To the men of the expedition, they were not only a major obstacle, but also provided a breathtaking view. (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.) |

IF man has destroyed and defaced many Lewis and Clark locales, so too has nature. The rivers themselves have capriciously meandered in places and swept away or altered sites. Because of a gross change in the Mississippi channel near St. Louis, the site of Camp Wood, once on the south bank of the Wood River in Illinois, is now on the Missouri side of the Mississippi. Another example is the Council Bluffs, Nebr., location, where the two captains held their first council with the Indians. Now, instead of being at stream's edge, it is 3 miles away from the river, which is not even visible from the spot. The wandering of the Missouri has obscured the site of Fort Mandan, N. Dak., the 1804-5 winter camp, and marred the nearby environment of the Mandan-Minitari-Amahami villages.

Nature has also altered the landscape. In some areas, major changes in vegetation have occurred. For example, above the mouth of the Platte, the hills and bluffs along the Missouri were for the most part bare of trees and shrubs in 1804-6. Today, the growth is so dense that one cannot see the river from the crests. The paintings and drawings of such artists as George Catlin and Karl Bodmer in the 1830's clearly show the difference.

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/lewisandclark/site.htm

Last Updated: 22-Feb-2004