PU'UHONUA O HONAUNAU NHP

A Cultural History of Three Traditional Hawaiian Sites

on the West Coast of Hawai'i Island

|

PU'UKOHOLA HEIAU NHS • KALOKO-HONOKOHAU NHP • PU'UHONUA O HONAUNAU NHP A Cultural History of Three Traditional Hawaiian Sites on the West Coast of Hawai'i Island |

|

|

Site Histories, Resource Descriptions, and Management Recommendations |

CHAPTER VII:

PU'UKOHOLA HEIAU NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE (continued)

B. Pu'ukohola Heiau (continued)

2. Historical Descriptions

a) Introductory Remarks

Considering that there were foreigners in the vicinity, and that the construction process for Pu'ukohola Heiau must have been quite impressive in terms of the number of people and the rituals involved, the paucity of firsthand accounts of this event or of the structure's appearance at the time of construction is disappointing. Because this was considered a very sacred temple, however, there really existed no opportunity for detailed Western observances until after the abolition of the kapu system.

b) Archibald Menzies, 1792-94

The first Western account we have of Pu'ukohola Heiau is that of Archibald Menzies of the Vancouver expedition. It is important because he viewed the structure soon after its construction while it was still being used for ceremonial purposes and thus was still regarded with fear by the common people:

In returning back to the waterside again, I went towards a little marae [temple], with an intention to view the inside of it, but my guides told me it was so strictly tabooed that they durst not indulge my curiosity without risking their own lives. They told me it was built about two years before in commemoration of a famous victory gained over Keoua, the last surviving issue of Kalaniopuu. . . . he invaded Kamehameha's territories, but meeting with a strong opposition from Keeaumoku and other chiefs, he was worsted in battle and he and eleven of his adherents were put to death near this marae. I was shown the spot on which this happened and where their bodies were interred, but their skulls are still displayed as ornamental trophies on the rail around the marae.

This marae is situated on the summit of an eminence, a little back from the beach, and appears to be a regular area of fifty or sixty yards square, faced round with a stone wall of considerable height, topped with a wooden rail on which the skulls of these unfortunate warriors are conspicuously exposed. On the inside, a high flat formed pile is reared, constructed of wicker work, and covered either with a net or some white cloth. There were also enclosed several houses in which lived at this time five kahunas or priests with their attendants to perform the ritual ceremonies of the taboo, which had been on about ten days. [73]

|

| Illustration 39. Kawaihae Bay, from sketch drawn by W.F. Wilson, ca. 1920. From Menzies, Hawaii Nei, opp. p. 52. |

Although it is difficult to understand how Menzies could describe this as a "little" temple, his description is probably a good indication of the heiau's original appearance. Note that he does not mention wooden images, which were usually an integral part of the furnishings of a luakini and the carving and erection of which have been described in the accounts of this temple's construction. [74] Because during this time Kamehameha was still in the process of reconquering and subjugating the other Hawaiian Islands, it would appear that the twelve skulls of those who dared oppose him were being displayed as a warning to others and as a sign of Kamehameha's patronage in military matters by Ku-ka'ili-moku.

c) Samuel Patterson, 1804-5

The next description, although scanty in comparison, is by the American seaman Samuel Patterson, who chronicled his travels in a merchantman during the period 1800 to 1817. He noted about 1804 that the Hawaiians

have a very extraordinary one [temple] on the island of Owhyhee, at Toahoi [Kawaihae] bay, which is very large, and the roof covered with human skulls, the white appearance of which, is discoverable at a great distance; but otherwise it is like unto the others. [75]

What sort of "roof" Patterson is referring to is unclear, although presumably he simply means that the skulls were positioned on the platform or on the walls surrounding the platform area.

d) Otto von Kotzebue, 1816-17

During 1816-17, Otto von Kotzebue, commander of the Rurick, led a Russian expedition in search of a northeast passage that visited Hawai'i in the course of its travels. His description of Kawaihae Bay adds little, except to note that "We saw here several morais, which belong to the chiefs of these parts, and may be recognized by the stone fence, and the idols placed in them." [76]

e) Louis de Freycinet, 1819

In 1819 an official French scientific and political expedition commanded by Captain Louis de Freycinet visited the islands shortly after the death of King Kamehameha. Jacques Arago, the ship's artist, left a very descriptive journal which is highly useful for some types of information:

On a hill opposite to that on which the house of Mr. Young is built, there is a very large moral enclosed by a stone wall about four feet high. The statues seen here are colossal, and regularly placed; I have counted above forty of them. The earth is covered with pebbles, evidently thrown there by design, although I have not learned the motive. A native who accompanied me related that on the board which was placed in the middle of the enclosure, were exposed the dead bodies of those who had been strangled, or stoned to death; that the place was tabooed for all the inhabitants, except the high priest, who repaired thither daily to consult the entrails of the victims. M. Rives [French adventurer who became Liholiho's secretary] afterwards confirmed what I had been told on these subjects. . . . [77]

This indicates that Pu'ukohola Heiau was used regularly up through Kamehameha's lifetime for religious services and that human sacrifices were a part of those services. Sometime between 1804 and 1819, it appears, the skulls of Keoua and his followers were removed and the customary wooden images became the dominating feature. This might have occurred around 1810 when the chief of Kaua'i acknowledged Kamehameha as supreme ruler, completing the formation of the island kingdom. At that time the warning symbolized by the skulls and the warlike atmosphere they generated would no longer have been necessary.

|

| Illustration 40. Drawing of Pu'ukohola and Mailekini heiau by L.I. Duperrey, 1819. The royal compond includes the king's residence with adjoining lanai and probably huts for retainers. Courtesy Bernice P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu. |

f) Missionaries Hiram Bingham, Henry Cheever, 1820

In 1820 Protestant missionaries arrived in Hawai'i on board the brig Thaddeus. They landed first in Kawaihae, knowing that was one of the favorite residences of King Kamehameha as well as the home of John Young, known to all sea captains as one of the king's trusted and very influential advisors — someone whom it would pay to have on their side. Learning upon their arrival of the death of Kamehameha and the abolition of the old religion, the missionaries were eager to proceed to Kailua for an audience with the new king. During their brief stay in Kawaihae, however, they had time to briefly reconnoiter. Missionary Hiram Bingham stated that:

The next morning [April 2] . . . I made my first visit on shore, landed on the beach near where Keoua and his companions had been murdered, and called on Kalanimoku at his thatched hut or cottage in that small uninviting village. With him, I visited Puukohola, the large heathen temple at that place. . . . Built on a rough hill, a little way from the shore of the bay, it occupied an area about 240 feet in length, and 120 in breadth, and appeared as much like a fort as a church. On the ends and inland side of the parallelogram, the walls, of loose black stone or fragments of lava, were 15 feet high, 10 feet thick at the bottom, and 5 at the top. On the side towards the sea, the wall consisted of several terraces on the declivity of the hill, rising from some 20 feet below the enclosed area, to a little above t. The frowning structure is so large and prominent, that it can be distinctly seen with the naked eye, from the top of Maunakea, a distance of about 32 miles. [78]

This description is also found in a journal of the Sandwich Island mission begun on board ship and possibly co-authored by Bingham, who adds in that document that the terraces "made convenient places for hundreds of worshipers [sic] to stand while the priest was within offering prayers and sacrifices of abomination." [79] Whether Bingham was told that people stood on the terraces during services or simply assumed that the terraces were used in that way is unknown. He continues:

In this enclosure [of Pu'ukohola] are ruins of several houses burnt to the ground, the ashes of various wooden Gods, remains of cocoanuts and other like offerings, the ashes and burnt bones of many human visitors, sacrificed to demons. At the foot of the hill is a similar enclosure [Mailekini Heiau] 280 feet in length and 50 in breadth, which had been used for the sacrifice of various beasts and plants, &c. The walls and areas of these open buildings, once tabooed and sacred, are now free to every foot, useless and tumbling into ruins. . . . [80]

According to this account, therefore, Pu'ukohola Heiau was destroyed and abandoned at the time of the abolition of the kapu system by Liholiho just as were others throughout the islands. This account also suggests that Mailekini was not the scene of human sacrifices. Despite Pu'ukohola Heiau's significant personal importance to Kamehameha, it would seem that his son did not view it with any particularly strong attachment, and certainly the usefulness of the heiau was over. However, when Liholiho returned to Kawaihae after the death of his father, he reportedly reconsecrated the heiau at Puukohola, following the traditional method of announcing one's new role as leader. Missionary Henry Cheever, sailing by the west coast of Hawai'i Island, mentioned: "We passed in the afternoon the Bay of Kawaihae, and saw the huge heiau which Kamehameha II. went to consecrate at the death of his father. . . " [81] Because this was the structure that supposedly provided Kamehameha with the power to become king, perhaps this ritual was seen as necessary to pass on the former ruler's power to his son. Marion Kelly speaks of Kawaihae as "the place where Kamehameha II returned after the death of his father to seek consolidation of his forces and consecration of his leadership role." [82] Kawaihae and Pu'ukohola Heiau appear to have retained some of their former spiritual and political significance at least immediately following Kamehameha's death, but having performed this last service in sanctifying Liholiho's role as king, the heiau structures were destroyed with the abolition of the kapu system.

g) Reverend William Ellis, 1823

The account of Pu'ukohola Heiau considered the most informative of these early sources is that by the Reverend William Ellis. Although very lengthy, it is presented here in its entirely because of the wealth of construction details. Much of the data on ritual ceremonies and procedures interspersed with the physical description was probably supplied by Ellis's native guides, who should have had a good knowledge of what went on at the site in more recent times. William Ellis was part of a delegation of Honolulu missionaries that made a tour of the island in 1823 to look for suitable locations for mission stations. Others in the group included Asa Thurston, Artemas Bishop, and Joseph Goodrich. While staying at Kawaihae, Ellis visited the temple of Pu'ukohola:

Its shape is an irregular parallelogram, 224 feet long, and 100 wide. The walls, though built of loose stones, were solid and compact. At both ends, and on the side next the mountains, they were twenty feet high, twelve feet thick at the bottom, but narrowed in gradually towards the top, where a course of smooth stones, six feet wide, formed a pleasant walk. The walls next the sea were not more than seven or eight feet high, and were proportionally wide. The entrance to the temple is by a narrow passage between two high walls. . . .

The upper terrace within the area was spacious, and much better finished than the lower ones. It was paved with various flat smooth stones, brought from a considerable distance. At the south end was a kind of inner court, which might be called the sanctum sanctorum of the temple, where the principal idol used to stand, surrounded by a number of images of inferior deities.

In the centre of this inner court was the place where the anu was erected, which was a lofty frame of wicker-work, in shape something like an obelisk, hollow, and four or five feet square at the bottom. Within this the priest stood, as the organ of communication from the god, whenever the king came to inquire his will; for his principal god was also his oracle, and when it was to be consulted, the king, accompanied by two or three attendants, proceeded to the door of the inner temple, and standing immediately before the obelisk, inquired respecting the declaration of war, the conclusion of peace, or any other affair of importance. The answer was given by the priest in a distinct and audible voice, though, like that of other oracles, it was frequently very ambiguous. On the return of the king, the answer he had received was publicly proclaimed, and generally acted upon. . . .

On the outside, near the entrance to the inner court, was the place of the rere [lele] (altar,) on which human and other sacrifices were offered. The remains of one of the pillars that supported it were pointed out by the natives, and the pavement around was strewed with bones of men and animals, the mouldering remains of those numerous offerings once presented there.

About the centre of the terrace was the spot where the king's sacred house stood, in which he resided during the season of strict tabu, and at the north end, the place occupied by the houses of priests, who, with the exception of the king, were the only persons permitted to dwell within the sacred enclosure.

Holes were seen on the walls, all around this, as well as the lower terraces, where wooden idols of varied size and shape formerly stood, casting their hideous stare in every direction. Tairi, or Kukairimoku, a large wooden idol, crowned with a helmet, and covered with red feathers, the favourite war-god of Tamehameha, was the principal idol. To him the heiau was dedicated, and for his occasional residence it was built.

On the day in which he [Ku-ka'ili-moku] was brought within its precincts, vast offerings of fruit, hogs, and dogs, were presented, and no less than eleven human victims immolated on its altars. And, although the huge pile now resembles a dismantled fortress . . . it is impossible to walk over . . . without a strong feeling of horror. . . [83]

h) Reverend Artemas Bishop, 1826

In November 1826 the queen regent Ka'ahumanu, residing on O'ahu, visited the island of Hawai'i for about two months. The Reverend Artemas Bishop accompanied her when she stopped at Kawaihae:

When we arrrived . . . she ordered the canoe to put ashore about twenty rods this side of the usual landing place. It was the place of her husband's [Kamehameha] former residence. The walls of his houses were standing, while every thing within and without was going to decay. She took a melancholy satisfaction in contemplating these ruins, and in pointing out to me the very places where Tamehameha used to sit, and where he slept. Directing my attention to the crumbling walls of a large heiau, [temple,] on an eminence, she said, "There is the spot where my husband used to worship his gods, and where many a human victim has been sacrificed. Let us ascend and see the place." "But," said I, "did you never go there?" "No," she replied, "it would have been death for any woman to approach its sacred precincts." So we ascended together, and when we had reached the top, and had taken a full view of the whole place, (a good description of which is given in the "Tour of Hawaii," [by Ellis]) she stopped short, lifted up her hands, and looking upwards, said "I thank God for what my eyes now see . . . Hawaii's gods are no more." She then showed me the holes in the wall, where the carved images of Tamehameha's gods once stood, and gave me their several names as we passed along. She then pointed out the altar where human and other sacrifices were offered. . . . She also described the dimensions of the buildings, which formerly stood in this immense enclosure, and added, — "But they were all destroyed in one day." [84]

i) John Kirk Townsend, 1834-37

John Kirk Townsend, an American ornithologist, embarked on a journey that included Hawai'i during the years 1834-37. Anchoring off Kawaihae, he went ashore, visited John Young's widow, and also took a look at Pu'ukohola Heiau. He noted, probably based on local information, that it had not been used as a temple since the abolition of the kapu system:

The heiau is built of stones laid together, enclosing a square of about two hundred feet. The walls are thirty feet high, and about sixteen feet thick at the base, from which they gradually taper to the top, where they are about four feet across. In the centre, is a platform of smooth stones, carefully laid together, but without any previous preparation, raised to within ten feet of the top of the wall. [85]

Townsend states that victims were sacrificed on this platform, "the gods standing around outside in niches made for their accommodation." [86]

j) James Jarves, 1837-42

James Jarves published a history of the Hawaiian Islands in 1843 in which he described Pu'ukohola as being

two hundred and twenty-four feet long and one hundred feet wide, with walls twelve feet thick at the base. Its height is from eight to twenty feet, two to six feet wide at the top, which, being well paved with smooth stones, formed, when in repair, a pleasant walk. The entrance was narrow, between two high walls. The interior is divided into terraces, the upper of which is paved with flat stones. The south end constituted an inner court, and was the most sacred place. [87]

k) Gorham D. Gilman, 1844-45

Gorham D. Gilman, in his journal of a trip to Hawai'i during 1844-45, visited Kawaihae and

Being provided . . . with a guide I walked to the old temple — It was one of the most famous as well as the largest of the old kings [sic] temples and like the fish pond at Kiholo cost a great deal of labour. It stands on the brow of a hill, overlooking the bay, and is some 75 or 100 feet above high water mark. Many a poor victim has been sacraficed [sic] to appease the anger of their gods. The holes where the Idols stood are distinctly visable [sic] the one in the center was very large and was seen at a great distance — immediately below this is a smaller one [Mailekini] — which likewise contained their gods. . . . [88]

l) Account, 1847

In June 1847 a party of men voyaged to Hawai'i to visit Kilauea caldera. On the way they landed in Kawaihae Bay:

After dinner, I took a stroll along the beach, and attended by a throng of natives, visited the heau [sic] or temple erected by Kamehameha I, during his residence here. It stands on an eminence, about one quarter of a mile from the village, fronting the sea. On the sea-shore stands [sic] two walls of what was probably the house for the priests, near by which, is a beautiful spring of warm water. In the rear of this, and part way up the hill, is [sic] the remains of a temple [Mailekini], or rather, an enclosure about 250 feet long, and 100 wide. The walls are built of small stones, and are about 30 feet thick at the base, and 20 feet at the top, and from 15 to 20 feet high; the side, fronting the sea, circular. Inland from this, and on the summit of the hill, about 300 feet above the level of the sea, is another similar enclosure, but of larger dimensions. The walls have fallen down in some places, but the outlines of the compartments inside the temple, are still visible. It is divided into apartments distinguished by the floor being raised or depressed. The floor is paved with small pebbles from the sea beach. Traces of a passage underground, are visible, though it is difficult to tell whether the two temples were connected by this passage. It has the appearance of an old fort, and might, perhaps, have answered this purpose. . . . [89]

This is the first mention of an underground passage on Puukohola, although it possibly simply refers to a lower walkway or passage in the platform area or along the east wall that some observers mistook for an underground passage that had formerly been covered over.

m) Samuel S. Hill, 1848

Samuel S. Hill, English author and traveler, arrived in Hawai'i on the Josephine in 1848 and visited Kawaihae's archeological sites:

The famous remains we were about to visit, consist of portions of the anciently principal heiaus, or temple of idolatrous worship, throughout the islands. .. . Of the once famous temple, in which were so lately celebrated the idolatrous rites of a cruel and barbarous religion, there is in reality but little more remaining than serves to confirm the accounts given by the earlier English navigators, and by many of the islanders still alive, concerning the ancient practices.

This heiaus [sic] consisted either of two departments, one of which was on a step of the rise of the land above the other, or of two distinct temples built and occupied at different epochs. After mounting from the beach about thirty or forty feet, we arrived at the first temple [Mailekini], or part of a temple, where we stood amidst a mass of rude, unhewn stones, among which nothing was distinguishable that might serve to throw any light upon the ancient usages of the priests and people. In front of it are still to be seen the remains of two small stone houses, which had been respectively the residences of Kamehameha I. and King Liholiho [Kamehameha II].

After climbing a pathless steep to a further elevation of about two hundred feet, we came to the later constructed heiaus [sic], or better conserved portion of the remains, where our guide now became very useful in explaining the character of what was here distinctly to be seen. The building appears to have been about 150 feet in length, and about 100 in breadth. Three walls of loose stones, of 15 or 20 feet in height, form the inner side and the two ends, while the outer side, at the edge of the steep, appears to have been open to the sea. There is no appearance of the temple having been covered. Besides the exterior walls, others remain, by which the building is divided into four unequal departments, with the character of which our friend was perfectly familiar. One large department, forming the centre, comprises two-thirds of the whole area, and the three other departments form a chamber at each end, and a narrow space within the longer of the outer walls. This latter portion seems to have been the place within which the god Kaili, to whom this temple was especially dedicated, and a number of inferior deities, stood exposed to the view of the people. Only a single pedestal, however, now remains, upon which it is well known formerly stood the principal god of Kamehameha I., Punkohula [Ku-ka'ili-moku]. . . . The spaces at the ends seem to have been occupied by the priests. That at the southern end is divided into narrow chambers, or gloomy cells, where the priests are said to have chiefly resided, and from which they issued only when the whole area of the grand department of the temple was filled with the worshippers of the idols before whom they practised their abominable rites, and at whose altars they offered their sacrifices of human victims. Part of an altar here remains, upon which they habitually burned these victims. But beneath the temple, out of the direct line, a projecting rock marks the spot upon which Kamehameha sacrificed to his god, the famous chief Keoua. . . .[90]

This account seems to suggest that a large number of worshippers could be found in the temple during certain rites. Whether or not these attendees spilled over onto the terraces is not known, although the missionary accounts presented earlier also mentioned this possibility. This account also suggests low standing walls within the interior dividing the platform into separate areas used either for ritual purposes or for priests' quarters.

n) Charles-Victor Crosnier de Varigny, 1855

Charles de Varigny provides what he states is an account of a visit to Pu'ukohola Heiau in 1855, but one needs to be careful in reading it because he confuses several bits of data with the construction of Mo'okini Heiau in northern Kohala. He states that the heiau about a mile from Kawaihae "is the largest and most intact still in existence in the archipelago. Its length is 350 feet, its width 150. The walls are 50 feet thick at the base, 8 at the top, and not more than 20 high." He continues,

In the northeast corner of its precincts, open to the sky, lies an enormous flat stone on which the victims were killed. It was there that they were dissected, the bones stripped of their flesh, picked clean, then tied in bundles and buried among the rocks which formed the foundations. At a short distance from this stone one notices several others of the same shape, with a shallow incised griddling, on which the flesh was burned. These stones have vitrified surfaces, a result of the fierce heat. [91]

|

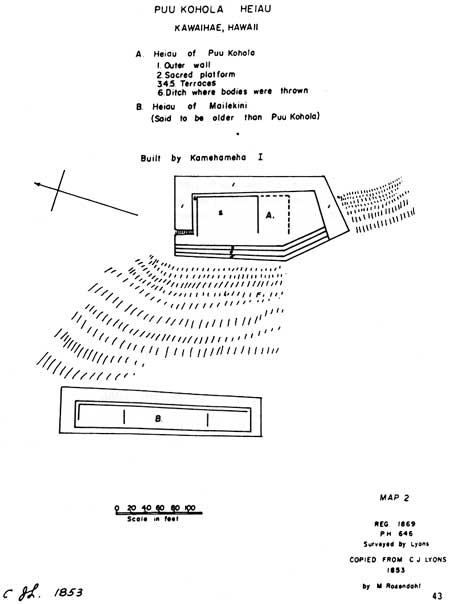

| Illustration 41. Ground plans of Pu'ukohola and Mailekini heiau. Sketch by M. Rosendahl from 1853 survey by C.J. Lyons. Map 2 in Kikuchi and Cluff, "Archaeological Survey of Puu Kohola Heiau and Mailekini Heiau," p. 43. |

o) Lady Jane Franklin, 1861

Lady Franklin, widow of the renowned Arctic explorer Admiral Sir John Franklin, visiting Kawaihae in 1861, went to see Pu'ukohola Heiau and described it as

a semicircular wall of rough stones about twenty feet high. The area is roughly paved and within it are the places used for sacrifice: that in the middle, a cavity filled in with loose stones, was for the human sacrifices; in front of it, that for beasts; to the left, for fruits. Immediately in front and a little below the level of this sacrificing area was a more closely paved terrace on which the highest Chiefs placed themselves; lower still was another for the inferior Chiefs; and lowest of all, the common people assembled. [92]

This certainly provides an explanation for the three terrace levels, but again it is difficult to know whether this information is accurate. The grandson of Isaac Davis accompanied Lady Franklin on this visit to the heiau, but whether he supplied the details on its construction and use is unclear.

p) Clara K. Whelden, 1864

The wife of the master of the whaling bark John Howland, out of New Bedford, Massachusetts, passed through Kawaihae Bay in 1864, but noted only that

Near the church are the remains of the place where they formerly had their savage feasts. From the ship it looks like an enclosure made of stones and rocks, and at first I thought is [it] was a Fort. [93]

q) Isabella Bird, 1873

Isabella Bird, traveling in Hawai'i in 1873 for her health, so benefitted from the climate that she stayed for nearly seven months. During that time she traveled around on horseback exploring local sites. Her description of Kawaihae was quoted earlier, but she also visited the nearby heiau on Puukohola, which stood "gaunt and desolate in the thin red air," entering it through a narrow passage between two high walls. Describing the structure as an irregular parallelogram, 224 feet long and 100 feet wide, she added that

At each end, and on the mauka side, the walls, which are very solid and compact, though built of lava stones without mortar, are twenty feet high, and twelve feet wide at the bottom, but narrow gradually towards the top, where they are finished with a course of smooth stones six feet broad. On the sea side, the wall, which has been partly thrown down, was not more than six or seven feet high, and there were paved platforms for the accommodation of the alii, or chiefs, and the people in their orders. The upper terrace is spacious, and paved with flat smooth stones which were brought from a considerable distance, the greater part of the population of the island having been employed on the building. At the south end there was an inner court, where the principal idol stood, surrounded by a number of inferior deities. . . . Here also was the anu, a lofty frame of wickerwork, shaped like an obelisk, hollow, and five feet square at its base. Within this, the priest, who was the oracle of the god, stood, and of him the king used to inquire concerning war or peace, or any affair of national importance. . . .

On the outside of this inner court was the lele, or altar, on which human and other sacrifices were offered. . . .

The only dwellings within the heiau were those of the priests, and the "sacred house" of the king, in which he resided during the seasons of strict Tabu. . . . [94]

Much of this information was probably gained from Mrs. Bishop's companions and merely repeats the interior arrangement described by Ellis and other earlier visitors. Whatever fact it was originally based on, the information had been passed down that the temple terraces were for the accommodation of observers of the ceremonies within.

|

| Illustration 43. View to southeast of Pu'ukohola Heiau showing structures along the shore between the temple and Kawaihae. Photo by W.T. Bingham, 1889. Courtesy Hawaii State Archives, Honolulu. |

|

| Illustration 44. Pu'ukohola and Mailekini heiau, n.d. (ca. 1889). Courtesy Smithsonian Institution National Anthropological Archives, Washington, D.C. |

r) Frank Vincent, Jr., ca. 1875

Traveler Frank Vincent, Jr., mentioned Pu'ukohola Heiau in his 1870s travelogue but provided nothing new in terms of a description. He did state that "Human sacrifices were offered in this temple as recently as the early part of the present century" — a fact he was undoubtedly told by local residents. [95] However, that observation seems to be corroborated by Jacque Arago's statement that human sacrifices were practiced as late as 1809.

s) John F. G. Stokes, 1906

In 1906 the Bishop Museum of Honolulu sent John F. G. Stokes to Hawai'i Island to conduct archeological research on temple remains. The work was part of a research design for Hawaiian archeology, focusing on recording and making plan drawings of temple structures on the various islands to document changes in construction style. Stokes noted that Pu'ukohola Heiau incorporated terrace, platform, and wall features, all with a partial veneer of ala, or waterworn stones. The walls on the north, east, and south were composed entirely of slightly rounded ala, while their narrow upper surfaces were paved with flat ala. The terraces to the west were filled in with rough stone like that found nearby, but faced with rounded ala and paved with flat ala. "Choicer" stones had been used for the large area of low pavement just to the south of the middle of the heiau. A large platform containing several divisions, suggesting house sites, occupied about one-third of the interior in the northeast quarter of the structure, rising about 4-1/2 feet above the floor. It was faced with ala stones and roughly paved with stones on the east and south; smooth coral fragments covered the northwest half. In the middle of the platform, leading in from the west, was a roadway of flat ala, two stones wide, ending in a single large ala convex on its upper surface. A ledge 2 feet high and 2-1/2 feet wide ran around the west side and south end of this platform.

Another platform at the southern end of the heiau stood three feet high; also paved with ala stones, it appeared to have been disturbed. Five pits existed in the platform, one in the southeast corner and the others forming a rough line near and parallel to the northern face of that platform. A local informant told Stokes the pit to the west was the lua pa'u and the lele had stood near it, on the western edge of the platform. Stokes was not sure, however, if these were ancient or modern pits because of the amount of disturbance.

Below this last platform and the low, smooth pavement described earlier, Stokes found a heap of loose stones in a sort of crescent form, which he did not think had been a later intrusion. On the eastern edge of the highest terrace to the west lay a strip of earth five feet wide, only a few inches below the level of the terrace pavement. Passages north and east of the main interior platform, between it and the outer walls, had been filled in by fallen stones. He did not think these had originally been paved.

The entrance to the top of the heiau was over a stone pavement inclining upward and to the south-southwest. East of the entrance a bench had been built into the slope of the west end of the northern wall, about 2-1/2 feet above the terrace pavement — a niche for a "guardian idol" he ventured. The heiau was constructed so that, although the west side was open, one could not get a close view of interior proceedings from the outside.

According to local information, Stokes noted, the smooth ala pavement was for dancing; also, a stone idol used to stand on the middle terrace and a wooden one on the lower terrace. [96] Stokes also mentioned that an elderly local native had told him that the body of Keoua had been cooked in an underground oven located on a ridge about fifty feet west of the northwest corner of Pu'ukohola Heiau. [97] In another group of notes, Stokes described the two small walls stretching from the corners of Pu'ukohola to the southwest and northwest, the latter beginning just east of the entrance. He suggested these delineated the limits of the sacred ground connected with the temple in ancient times. [98] In other miscellaneous information, he noted that the terraces, three in number, bulged outward, following the contours of the ground. The lower two were narrow, but the upper one broadened out as the main floor of the heiau. He also said that small idols had been found hidden within the structure and conjectured that the pits in the south end could have resulted from digging for other hidden statues. But he believed that the four pits arranged in a line could have been enlargements of holes for large idols. [99]

Stokes's plan of Pu'ukohola Heiau placed the 'anu'u and lele according to Ellis's description. The site of the drum, or king's house, he placed on the south projection of the main platform. He also inserted other traditional temple structures, such as the hale mana, waiea, hale umu, and guardhouse. The large, long mana he placed on the east side of the platform, with the stone path leading to it. He added a wooden fence on the upper terrace, believing this explained the strip of earth and loose stones dividing the upper terrace lengthwise. This fence would help define the limits of the sacred portions of the temple, a necessity if there were ali'i or commoners standing on these terraces. [100] Perhaps this is the fence on which Kamehameha displayed the skulls of Keoua and his followers.

|

| Illustration 45. Ground plan of Pu'ukohola after John F.G. Stokes, 1906. Map 4 in Kikuchi and Cluff, "Archaeological Survey of Puu Kohola Heiau and Mailekini Heiau," p. 45. |

t) Thomas Thrum, 1908

Thomas Thrum, in his Hawaiian Annual for 1908, states that

The most familiar of all heiaus of the islands is the famous one at Kawaihae, named Puukohola, from its being on the travel route of so large a portion of residents and visitors, and figures prominently in history in connection with Kamehameha's supremacy. It is generally referred to as the last heathen temple erected, but on this point there are evidences otherwise.

The earliest descriptive account given of this celebrated heiau is that of Ellis from his visit in 1823, at which time it was doubtless in perfect order, being then only 30 years since its completion by Kamehameha, and but four since its disuse. [101]

u) Gerard Fowke, 1922

Gerard Fowke, representing the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., performed some archeological work in Hawai'i in 1922, during the course of which he examined Pu'ukohola Heiau. Not much new information was gleaned from his reconnaissance, however:

The "Great Temple" built by King Kamehameha I is on a bluff 100 feet high, separated from the beach by a low level space 100 yards wide. This flat contains many stone structures, but their number, design, and character can not be ascertained on account of the almost impenetrable growth of algaroba. One of them is a rectangle [Mailekini Heiau] about 50 by 150 feet, the walls high and thick; probably it is an older temple. There is some modern work here, because in one place a wall is cemented, perhaps by ranchmen.

The "Great Temple" measures 80 by 200 feet on the outside, 50 by 150 feet inside, longest north and south. The two ends and the side toward the land are nearly intact and from 10 to 20 feet high according to the surface of the ground. At the north end, inside, is a platform 80 feet north and south by 45 feet east and west, the four walls carefully and regularly laid up, the space within them filled with large stones, and the surface leveled with beach pebbles. It ends 4 feet within the wall next the sea, the top of this wall being on a level with the bottom of the platform. At the south end is another platform 40 feet east and west by 20 feet north and south, abutting against the east and south walls. A step or terrace 6 feet wide extends the full length of its north side. It has a less finished appearance than the platform at the north end. The central space, between the two, is paved with large stones which apparently pass under both platforms and extend from the foot of the east wall nearly to the west wall, a slight ditch separating it from the latter. The west wall stands below the top of the slope, and its outer face is from 10 to 20 feet high, in three platforms each 8 feet wide. On the slope below are several structures a few feet square formed by two parallel rows of stones with a cross wall at the lower ends, the cellar-like space thus inclosed being filled with pebbles to a level with the top of the walls.

From the northeast [southwest?] and northwest corners long walls extend northwest and southwest toward the beach. Their outer ends are lost in the thicket. [102]

v) Oral Interview, 1919-20

These are the few historical accounts of Pu'ukohola Heiau that provide any type of detailed description of the structure. In addition, an oral interview between Rose Fujimori and Solomon Akau mentions a large A-frame of a former grass house facing the ocean, with a door facing sideways, on top of the heiau on the 'ili'ili ca. 1919-20. Nothing of its origin or use is known, but it was certainly a later addition that might account for some of the disturbance noted by Stokes. [103]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |