Contents Foreword Preface The Invaders 1540-1542 The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest 1542-1595 Oñate's Disenchantment 1595-1617 The "Christianization" of Pecos 1617-1659 The Shadow of the Inquisition 1659-1680 Their Own Worst Enemies 1680-1704 Pecos and the Friars 1704-1794 Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas 1704-1794 Toward Extinction 1794-1840 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

A Decade of Distress Famine and invasion—the two calamities lamented by Father Bernal in 1669—cast ever lengthening shadows across the land during the decade of the seventies. Questions of royal or ecclesiastical privilege paled before doomsday predictions. What did it matter that a Franciscan sat as ecclesiastical judge instead of a secular priest if in truth the barbarians were at the gates? In crisis, the factions of church and state, so long estranged in New Mexico, groped toward mutual aid. At first they fell short. An Apache Campaign Aborts Back in February 1668, Gov. Fernando de Villanueva, beset by news of lethal Apache raids on Spanish homes in the Salinas and Piro regions, had appealed to Father Custos Juan de Talabán. A council of war in Santa Fe called for retaliation in force, fifty to sixty soldiers plus Pueblo auxiliaries, for a two-month campaign. The governor begged the custos to throw open mission larders to provision such an expedition and to loan as many horses and mules as needed. Not so fast, replied the Franciscan. For His own good reasons God had visited upon the whole land "both the plague of locusts that laid waste the fields and also the scourge of crop failure." The custos had been forced to succor some conventos with seed from others to keep missionaries in the field. When Santa Fe was starving, Santo Domingo had sent maize, as had Fray Diego Enríquez of Pecos. Now, starving Santo Domingos were out scavenging for food. Others lined up at the sound of the bell for a dole of maize. Still, despite all this, said Talabán, he would try to scrape together provisions for the campaign. As for the horses, so essential to their scattered ministry, he would have to consult some of the other missionaries. After all, they had acquired these animals through their own diligence and with their alms.

The half dozen Franciscans who gathered at Santo Domingo were unanimous. The custos should solicit from the conventos whatever provisions they could spare—a total of possibly fifty fanegas—as well as a loan of horses and mules. It was not the intention of the friars that blood flow and death follow from this campaign, only that greater misfortune be averted. Their unusual "charitable aid" was being extended in this crisis for defense of Christianity and the churches. Under no circumstances should it be taken as a precedent. Had not the king granted encomiendas to armed men who pledged in return to defend this land at their own expense? As for the animals, the friars demanded a legal guarantee that horses and mules lost or killed during the campaign would be replaced. Without them, how could they get round to administer the sacraments? Politely, Governor Villanueva thanked Custos Talabán in the king's name for the offer of provisions, but he balked at the guarantee. That hardly seemed appropriate. This was not an adventure or an aggressive war, rather it was a general defense of the realm, of conventos and of friars as well as of everyone else, Christians all. Reconvening his council, the governor presented, the friars' offer. No one thought fifty fanegas were enough. Guarantee the horses? Who did the Franciscans think they were? With that, the retaliatory campaign was scrapped. [70] The Apaches Unchecked Don Juan de Medrano y Mesía had assumed the unhappy governorship in November 1668. During the first seven months of his term, Apaches killed, by his tally, six Spanish soldiers and three hundred and seventy-three Christian Indians, stealing more than two thousand horses and mules and as many sheep. In one assault on Ácoma in June 1669, they abducted two Ácomas alive, murdered twelve, and ran off eight hundred sheep, sixty cattle, and all the horses. A small party under Capt. Francisco Javier gave chase, caught the enemy, and were nearly overwhelmed. Cristóbal de Chávez, the dagger-wielding Spaniard who had put the fear of the devil into Father Nicolás de Enríquez, died in the fray. Governor Medrano vowed to launch from Jémez a force of fifty soldiers and six hundred Christian Indians. But he would need the friars' help. "If these voracious enemies are not punished and their milpas not laid waste," wrote the governor, "they will surely devastate this kingdom. That is what those Apaches shout for all to hear and in Spanish! Those of the Gila, the Salineros, and those of La Casa Fuerte have come together"—Apachean groups west of the Rio Grande, including Navajos, ranging from the headwaters of the Gila north to the San Juan. The governor implored Father Talabán to forward to Jémez whatever supplies the conventos could contribute. Again the Franciscan answered with a tale of woes. Driven by their hunger, even the mission Indians had taken to robbing the conventos. He had been obliged to succor Senecu and Socorro, and now Ácoma. If he had not sent aid to the Tewa conventos of Nambé, San Ildefonso, and San Juan, their ministers would have had to leave. Without the mission dole of seed to the Indians, claimed the superior, "there would not now be an Indian alive." Several of the conventos had already contributed wheat and maize to the governor. From Jémez, aid had gone as well to Galisteo, Sandía, and Zia. Now only Pecos had anything to spare, twenty fanegas of wheat, "and this is taking it from the pueblo's very sustenance." In addition to the wheat from Pecos, Talabán volunteered two hundred sheep and two dozen cattle, as well as a Franciscan to serve as chaplain. Again, this aid must not be considered a precedent. It was being freely given for defense, to destroy the enemy's crops, not his person. Exactly, replied the governor who exulted over the friar's response. "I shall remain so grateful for such an act that I shall place it as a blazon on the doors of my house, not forgetting the succor of provisions this holy custody has given me in such need." [71]

The immediate results of the campaign are not known. If the Spaniards and their Pueblo allies did destroy Apache and Navajo crops, they only succeeded in aggravating the western front. The raids did not cease. When the hungry enemies fell on Hawikuh four years later, they utterly consumed it. But at least by then, friars and governors had recognized that only in mutual aid was there any hope of survival. Southern Front under Assault Another theater of Apache warfare stretched across southern New Mexico imperiling the Piro pueblos as well as a long unguarded section of the camino real. East of the Manzano Mountains, the Apaches of Los Siete Ríos had begun pummeling the Salinas pueblos. In one all-out assault, a strategy that became more and more characteristic of the 1670s, Apaches overran the pueblo of Las Humanas at harvest time in 1670, sacked the church, slew eleven residents, and carried off thirty-one captives. In the years to come, no fewer than six Piro and Salinas pueblos perished in drought, famine, disease, and Apache onslaught. [72] Even as Apache war quickened to the south and west, Pecos remained becalmed. As far back as the 1640s and 1650s, there had been mention of random raiding in the area by Apaches from the mountains of northeastern New Mexico, evidently ancestors of the Jicarillas. From time to time, an unwary Pueblo died at their hands almost within the shadow of Pecos. Governor López de Mendizábal had cautioned the Pecos transporting boards to the casas reales in Santa Fe to keep an eye out for lurking Apaches as they came through the sierra. Still, nowhere in the documents chronicling the critical state of affairs in New Mexico does one find reference to the plunder of Pecos. [73]

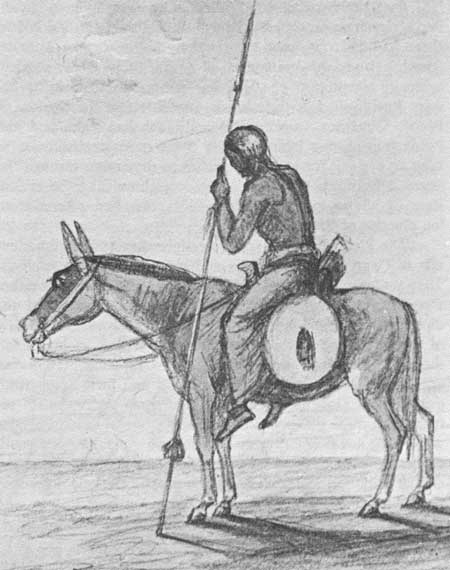

Trade Fairs at Pecos The Plains Apaches seemed to have kept coming in annually to Pecos laden with hides and meat and Quivira captives. They preferred to be the middle men in the slave traffic rather than the object of it. Evidently the lure of trade and the diplomacy of Pecos traders like El Carpintero offset the effect of heavy-handed Spaniards operating on the plains. Even though Governor López had sent out in September 1659 "an army of eight hundred Christian Indians and forty Spaniards," even though Governor Peñalosa's man Juan de Archuleta retrieved from the plains about 1662 some of the Taos renegades who had fled their pueblo twenty-two years before—still, Father Posada, at Pecos between 1662 and 1665, observed the annual trade fair. That it continued, despite the calamities that threatened to destroy the colony, explains at least in part why Pecos had provisions to spare. [74] | ||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||