|

Hubbell Trading Post

Administrative History |

|

INTRODUCTION

Hubbell Trading Post is not a "destination" for most of the people who arrive there. The authors' first trip to the trading post, in October of 1981, is probably fairly representative of most of the visits there. We were on a trip to the Grand Canyon. Before starting for home (Santa Fe) we decided to look at our maps to see if there might be something of interest to see along the way. And there, just west of a town called Ganado, we found a little red square with an arrow pointing at it and the words Hubbell Trading Post National Hist. Site.

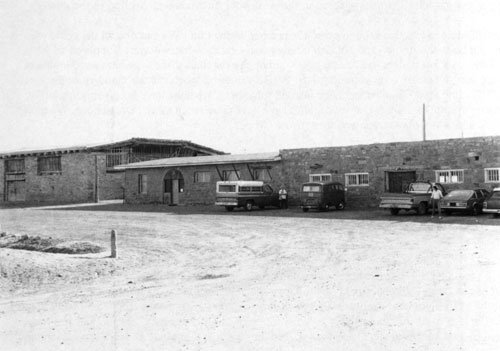

Figure 3. The authors first visited the historic site in October, 1981. The only photo they took that day shows part of the wareroom, the curator's office and storage area, and, in the background, the barn. A Manchester photograph.

We had heard of the place, but we had never been there. If we drove through Cameron and Moenkopi, we noted, and took 264 easterly toward Gallup, we would be on a road with orange dashes paralleling it. Instead of having to escort hundreds of tractor-trailer rigs along 140, then, we would be able to drive at least part of the way back home on a "scenic route." So our first trip to Hubbell Trading Post was simply a why-not? decision based on the hope that driving that way would be more interesting than getting back on I-40.

Ever since starting work on this administrative history we have been trying to recall what that 1981 visit meant to us. We've probed the wells of memory in hopes of finding there something that might benefit the people who will be using this work. We entered the trading post that day. We recall seeing the baskets on the ceiling. We didn't buy anything. Then, unlike the majority of visitors, we took advantage of the tour through the house. We saw more baskets on the ceiling there, dark rooms, and old furniture. Back outside, near the bread oven, we recall looking at the garden. Cornstalks stood in the weak sun, brown leaves rustling in the wind.

Trader Bill Malone was there, but we don't remember seeing him. We can't recall the guide who took us through the home; and we can't remember exactly what we were supposed to have learned about Indian traders and trading posts, although ever since that day, whenever the subject came up, our notion of what a trading post is like would be whatever we could remember of Hubbell Trading Post. So we must have learned something, we must have been somehow subtly impressed, in spite of the fact that we couldn't have been there much more than an hour. We took one black and white photograph and then drove away.

Nine years later to the month, driving the same green Chevy pickup but this time approaching Ganado from the east, we went to Hubbell Trading Post to start work on this administrative history. We researched and wrote for over a year. We came to know Dorothy Hubbell, Ned Danson, and other people who were instrumental in bringing Hubbell Trading Post into the Park System. Doing our research, we returned to the trading post several times. We realized after a while that the post seems to have an aura all its own, and we think we know the source of that aura.

Hubbell Trading Post is not just an old trading post; it is a window to a very rich world. A world of traders and trading posts, of military campaigns against Indians, the campaigns and marauding of those Indians against the people history brought upon them. Hubbell Trading Post was one of the focal points during a collision of conflicting cultures. And the site has been occupied by man probably since man first walked into the area thousands of years ago and found water here; he has left dwellings, artifacts and burials here. The place is rich in the lore of arts and crafts. Significant people lived here, worked here, passed by here. Although small in area, Hubbell Trading Post is undoubtedly one of the richest cultural resources owned by the American people.

During our research we learned that one of the trading post's superintendents reportedly complained that he felt like the manager of a grocery store. Surely he missed what Hubbell Trading Post is all about. When you do business with Bill Malone you are taking part in a tradition that goes back, now, 115 years; Bill is the most recent link in an unbroken chain that you can follow right back to the mid-1870s. In the West, that spells Tradition.

Location, Access, and Public Facilities

Hubbell Trading Post is located about a half mile to the west of what can be considered the center of Ganado, Arizona. Ganado is up in the northeastern corner of Arizona in the Navajo Nation, 53 miles northwest of Gallup, New Mexico, 190 miles west of Albuquerque, and 156 miles east of Flagstaff, Arizona. Ganado is 35 miles north of Chambers, Arizona, which is on I-40. US 191 and Arizona 264 cross in Ganado.

If you are driving from the east, it is recommended that you take US 666 north out of Gallup and then Arizona 264 west toward Window Rock, Arizona. The nearest rail connection is at Gallup, and there are commercial airports at Gallup and at Winslow, Arizona (124 miles). Rental cars are available in connection with airline transportation.

Advertised lodging is unavailable at this time in Ganado. The historic site has a VIP trailer, but if promised lodging there suddenly becomes unavailable to you (and this seems to be a chancy matter on the best of days), it is recommended that you stop over in Window Rock at the Navajo Nation Inn.

However, the citizens of Ganado and the historic site are aware that limited housing is available on the Presbyterian Hospital grounds. The hospital, now called Sage Memorial Hospital and operated by the Navajo Nation Health Foundation, is in fact a complex of buildings that has grown up during the past seventy years. The hospital land, like the land at the historic site, is not part of the Navajo Reservation. The hospital maintains "cottages " for visiting medical people and others who are there on business. If the cottages are not occupied, the hospital will rent them to anybody else.

Ganado is 6300 feet above sea level. This is high-desert country, the Colorado Plateau. The landscape is open, vistas large. Summer days are dry and warm, summer evenings cool. Scattered rainfall---sometimes short-lived, violent storms---are part of many summer afternoons. Annual precipitation is about fifteen inches. Winter days are dry and sunny, warm in the sun, cold in the shade. Winter nights can be quite cold, the temperature dropping below zero Fahrenheit. There is a year round temperature differential between day and night of about thirty degrees. Spring, when almost daily winds blow dust and grit, can seem like the worst season of the year. Winds are generally westerly. Last frost is about mid-May, first frost mid-October.

About 1500 people, primarily Navajo, live in the vicinity of Ganado, which, like every other town on the reservation, is not an incorporated town with city or town limits. There are little or no zoning restrictions on the reservation; there is the danger that something truly unsightly could be built next to the historic site.

Ganado has limited tourist services. There is a post office here, a small grocery, two restaurants, two gas stations, a substation of the Navajo Police, and a volunteer fire department with an ambulance. There are no supermarkets here, but besides Hubbell Trading Post there is the Round Top Trading Post. Possibilities for any kind of shopping are exceedingly limited. Many NPS employees make weekly expeditions to Gallup for supplies.

Ganado has five churches, Catholic, Mormon, Presbyterian, Baptist, and Full Gospel. The local public schools include all grades from preschool through high school. The Navajo Community College offers about fifteen courses at Ganado, including (if there are enough students) classes in the Navajo language.

Ganado is one of the 110 "Chapters" of the Navajo Nation and has its own chapter house, the Navajo equivalent of a town hall. Navajo chapters were established allover the reservation in the 1920s as units of agricultural extension services. They came to be meeting places to discuss issues and over the decades developed into a form of local government. Generally speaking, total consensus is required before the Navajo will move on an issue; for the impatient Anglo new to the Navajo Nation, "progress" on an issue can seem slow, now and then unattainable. NPS employees must learn to work closely with the local chapter in reference to mutual concerns.

The Navajo Reservation encompasses about 25,000 square miles, and approximately 165,000 people are scattered across this land. Individual Navajo do not "own" the land on which they live, farm, graze their cattle, and gather firewood. Use of a given area or resource is allowed by permit from the Navajo Nation government.

Window Rock, Arizona, is the seat of government for the Navajo Tribe. The Tribal Council meets there four times a year and the Bureau of Indian Affairs has its offices there. Window Rock has developed into a considerable community. There are two supermarkets in town as well as a string of the familiar fast food places one might drive by on the road into almost any American town. No liquor, wine, or beer is sold legally on the reservation.

Utility Systems

The site's water supply, sewage, and electrical power is provided and maintained by the Navajo Tribal Authority. Telephone services and cable TV are provided by the Navajo Communications Company.

Economic Trends

The nearest major employment centers are Phoenix and Albuquerque, many miles from the Navajo Nation. Flagstaff and Gallup provide a more limited employment opportunity. Unemployment figures for the Navajo are high, reportedly over forty percent. Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site has been authorized to use the "Contiguous to the Area" hiring authority for temporary positions and selected continuing positions. Other than that, there is no written policy regarding the hiring of the Navajo. We are guided by the usual equal opportunity laws, etc., plus just old common sense." [2]

Development on the nearby Navajo and the Hopi Reservations includes mining, coal-fired powerplants, roads, tourism, and recreational facilities.

On Avoiding A Gaffe

Social customs and personal conduct among the Navajo cam seem "foreign" to a visiting run-of- the-mill American. The following points were worked up by Terry Nichols in 1982 when she was Supervisory Park Ranger at Hubbell Trading Post. [3] This is an adaptation of her work.

1. To be outgoing and loud may be considered overly aggressive conduct. On the other hand, Navajo may expect such behavior from their American cousins and they may not be totally outraged or frightened by it.

2. To be reserved, quiet, gentle, not outspoken is considered the Navajo way. Older people are deferred to, treated with respect, not ignored.

3. Do not be derogatory about Navajo customs, politics, police. On the other hand, if you are a knowledgeable "foreigner" with some authority--an Indian trader, for example--your opinions may be considered. Most Navajo feel their way of life is perfectly adequate.

4. Many traditional Navajo were taught when they were small that white people are not to be trusted. Such Navajo may remain--understandably--aloof and cautious until they can see, possibly after years of observation, that you may be as worthwhile a person as you seem to be. Terry Nichols said that she was at Hubbell Trading Post for a couple of years before some Navajo accepted her. [4]

5. Do not assume that a Navajo will know all about the National Park Service. Chances are they don't know anything about it.

6. To the Navajo, you are a visitor who will very likely be here just a short time. They will be pleased if you come to understand something of their approach to life.

7. Trying to learn a little Navajo is one way to bridge the culture gap. If nothing else, it may give the Navajo a chance for a chuckle or two. Terry Nichols recounted how when she tried to say that a particular hill was high, she suggested instead that it was pregnant, which was surprising news to her listeners. [5]

8. At social gatherings, with food and drink available, if one is quiet and reserved, smiling, opportunities for some sort of communication should arise.

Except for dedicated readers of Tony Hillerman's novels, few people know very much about Navajo social mores. The Navajo, however, get a chance to see other Americans every night on TV, and such exposure would tend to make even the strongest people cautious.

Figure 4. Hubbell Trading Post as seen from the top of Hubbell Hill and looking across the Pueblo Colorado Wash. The date is May, 1966. The bridge seen to the left was removed in the mid-1970s. Photographers Bill Brown and John Cook, NPS photo, HUTR Neg. 186.

The Navajo language

The Navajo language is described as complex and difficult to learn. Few NPS employees have become fluent in the language. Navajo has few points of reference for people who grew up speaking and studying European languages only.

Physical Description of the Historic Site

Hubbell Trading Post is situated on 160 acres of land, about 110 acres of which are irrigable. The land can be irrigated through a series of ditches planned and built by J. L. Hubbell, and will be irrigated as soon as the dam at Ganado Lake is repaired and the ditches are cleaned out and repaired. John Cook, Hubbell Trading Post's first superintendent, recalls seeing water in all the ditches. [6] The farmland rises gently north to south and is terraced to hold the water at many levels. Dorothy Hubbell described how her husband Roman would spend days in the fields with a transit, trying to level the land for proper irrigation and farming. [7]

The visitor comes to the complex of buildings at the end of the entrance road. The imposing collection of buildings are all of adobe or rock construction and date from the late nineteenth century to the 19405: home, trading post, wareroom, wareroom extension, barn, manager's residence, guest hogan, chicken coop, bread oven, bunkhouse, hogan-in-the-lane, visitor center, root cellar, corrals, sheds.

To the left along the entrance road, close to where the entrance road meets the highway, lie the employee living quarters, a group of mobile homes and the superintendent's "modular" home.

The Pueblo Colorado Wash, a broad, deep streambed, cuts the north side of the land. During local storms the wash may flood, and in the past it has caused erosion along its banks and some destruction to Wide Reed Ruin, an Anasazi (ancient Indian) pueblo ruin of surprising significance. Because of the availability of water in the midst of a vast and generally dry landscape, the site has been used and occupied for thousands of years. Indian burials and collections of potsherds and lithics have been found in several places on the historic site. Except for the lack of farming, the trading post looks much as it did in, say, 1920 or 1930, and a lot of effort is expended in keeping it that way.

History of the Site to 1957

In an oft-quoted statement made in 1907, John Lorenzo Hubbell said: "The first duty of an Indian trader, in my belief is to look after the material welfare of his neighbors; to advise them to produce that which their natural inclinations and talent best adapt them; to treat them honestly and insist upon getting the same treatment from them; ...to find a market for their products and vigilantly watch that they keep improving in the production of same, and advise them which commands the best price. This does not mean that the trader should forget that he is to see that he makes a fair profit for himself, for whatever would injure him would naturally injure those with whom he comes in contact."

This business philosophy kept the Hubbell family in business from the mid-1870s until 1967, and this is still the general aim of the traders who now operate the business under the auspices of Southwest Parks and Monuments Association.

Figure 5. John Lorenzo Hubbell in 1908. This is one of the famous "Red Heads" done by E. A. Burbank. There are many Redheads at the site, most of them portraits of Indians, and they are conte-crayon drawings on paper. NPS photo, HUTR Neg. 1901.

Hubbell was born in Pajarito, New Mexico, near Albuquerque, in November of 1853. His parents were James Lawrence Hubbell, from Connecticut, and Julianita Gutierrez, of New Mexico. John Lorenzo went to Santa Fe to attend Fraley's Presbyterian Academy, and then he took a clerking job in the post office in Albuquerque. After about a year in the post office, he set off on his own for the Utah Territory.

Hubbell was a clerk for a time at a Mormon trading post at Kanab, Utah. While there, in 1872 he was reportedly seriously wounded in a fight at Panguitch, Utah. Hearsay tells us that the incident may have been about a woman who was the wife of another man, and the "fight" may have been nothing more than John Lorenzo getting plugged as he was exiting a bedroom by way of a window. However that may be, a real fight or wounds for the sake of dalliance, the lively young man thought it better to ride out of town. He headed south, which is important for the rest of the story.

Legend tells us, too, that some Paiute Indians picked up the wounded John Lorenzo and took care of him until he had regained mobility. We next find him working as an interpreter at Fort Defiance, Arizona, and then as a clerk at the trading post at Fort Wingate, New Mexico. With some clerking and trading post experience under his belt, John Lorenzo went to Ganado Lake in 1876 and opened his first trading post at what was then called the Hardison place. He operated there until he bought the Leonard Trading Post in 1878. The original Leonard buildings were out in front of the present home and trading post. The Leonard buildings were razed in the 1920s.

J.L. Hubbell had a partner in the early years, C.N. Cotton, and during the years of this partnership Cotton assumed much of the day-to-day operation of the trading post while Hubbell pursued a political career. John Lorenzo was sheriff of Apache County and he was a territorial senator during the years before Arizona became a state. His political ambition ended when he was defeated in an expensive race for the U.S. Senate.

In the 1890s, long before the disastrous political race for the Senate (1914), Hubbell became sole owner of the trading post, and he concentrated more of his time on expanding the operations. Cotton moved to Gallup, New Mexico, where he opened a warehouse; he provided wholesale merchandise for Hubbell and other Indian traders, and he became very important in the marketing of rugs and blankets in many parts of the United States C.N. Cotton is a considerable study all by himself.

J.L. Hubbell was married to Una Rubi (1861-1913) of Cebolleta, New Mexico, in 1879. They had four children: Adela (1880-1938), Barbara (1881-1965), Lorenzo (1883-1942), and Roman (1891-1957).

Hubbell's developed into one of the most successful and influential of the trading posts. During the early decades of the business the Hubbells branched out considerably. A truly detailed study of all of their enterprises has never been made. Many boxes of business correspondence receipts, ledgers are in the hands of the University of Arizona. The Hubbells bought out or opened trading posts in other areas. They did freighting, for themselves and others. Apparently they even opened a used car business. J.L. Hubbell was a businessman right down to his bone marrow. As he became more influential, people came to know him as "Don" Lorenzo, the Don being a Spanish term of respect.

Figure 6. John Lorenzo Hubbell holds one end of a rug. A Navajo woman, probably the weaver, holds the other end. This Ben Wittick photograph from probably the 1890s shows the north end of the trading post. NPS photo, HUTR Neg. RP-312.

It seems likely that his concern for his Navajo neighbors and customers did surpass the necessity of a purely business relationship. He had true friends among the Navajo. He was of use to them, and of course he needed them. (A trader who was a cheat, who was of no use to the Navajo, would not last long.)

The relationship between the Navajo and the trading post continues to this day. The trading post is still a place for them to buy supplies and to trade crafts. Now that it is a historic site, it brings people and money to the area.

The trading post as it is now could not exist without the support of the Navajo. The trading post needs their crafts. Hubbell Trading Post is considered something of an economic asset in the area, and it is in the interest of the tribal council delegates and the Ganado governing body, and the administrators of the trading post, to remain on good terms, and to exchange ideas and discuss mutual problems.

Don Lorenzo's influence on the local culture was considerable. Many Navajo rugs look the way they do simply because Hubbell advised the weavers as to which designs would sell, which others might not. The "Ganado Red" is a style associated with Hubbell Trading Post. He advised them on farming matters, and the farm at the trading post set an example. J.L. Hubbell tried to keep pace with some modern developments. He was a strong, intelligent businessman with a large dose of compassion running through him, a man whose sensibilities allowed him to find room for another culture; he was perfectly fluent in Navajo. He was also a frontiersman, so his talents lay in many directions. There aren't many specialists on a frontier.

The Hubbells were appreciative and acquisitive. They came to own one of the largest collections of art and artifacts in the Southwest, most of which is still at the trading post. J.L. Hubbell was famous for his hospitality. Ganado has always been one of the crossroads of the Navajo Nation The trading post has been a shopping place for Navajo and a stopping place for travelers for over a hundred years.

One traveler who stayed at the trading post in 1917 was Donald Scott, who would later become an authority on the Old West and the director of Harvard University's Peabody Museum. [8] In 1958, when he was driving back from California, Scott took the opportunity to revisit the Hopi and Navajo country. In a June 9, 1958, letter to the then director of the Peabody Museum, J. O. Brew, Donald Scott described the experience:

"...again I was deeply impressed by [Hubbell Trading Post's] historic associations

As you know it stands head and shoulders above all other trading posts, and while its trade has fallen off in these later days it still stands as a unique monument of the early days of the Indian trader and the Navajo economy. It was founded in 1874 by John Lorenzo Hubbell, a man of such character that his reputation soon spread through all the Navajo country.

The great business in wool, pinon nuts and other goods traded for his commercial stock lead [sic] to the building of a striking adobe compound of warehouses and stores. Because of the danger in an unsettled land, the group of buildings has partly the aspect of a fort. In a way its character is half way between the forts of fur trading days, such as Laramie and Bridger, and the more peaceful posts of today.

I had a long talk with Mrs. Ramon [sic] Hubbell in the dining hall where Roosevelt Taft and a great many other celebrities have eaten in days gone by. The family which made the name Hubbell, like that of Morgan a synonym for honesty and power, has now reached its end. Don Lorenzo's older son, Lorenzo, whom you knew, succeeded his father and established himself as far west as Winslow. On his death the younger son, Ramon, took over. It is his widow who is now managing the post, and I found her a woman of exceptional character and charm.

Mrs. Ramon feels she must dispose of the property.... It seems to me that some way should be found to perpetuate the post. Its physical character--the great adobe compound, warehouses, stores and patios--and its historic associations are a unique reminder of a colorful and important period in our relations with the native tribes. Much as I wish other monuments of the past preserved, there are many covered bridges, many historic houses and churches, but this trading post is unique as I am sure you would testify.

When I first saw Ganado it was a picturesque spot surrounded by the camp-fires of Navajos who had come by horseback or in farm wagons from near and far to trade. The warehouses were bursting with wool and Don Lorenzo, quiet but powerful, made a deep impression on me. The Navajo are still there in this cedar-dotted, good grazing land.... [9]

Figure 7. Navajo wagons at Hubbell Trading Post circa 1910. Some Navajo would trek in from considerable distances, camp overnight. Hubbell Hill rises in the background. Copy of photo from Huntington Library, San Marino, California. HUTR Neg. RP-200.

The Hubbells started farming their land very early in the twentieth century. A system of irrigation ditches was developed for their own land and to get water from Ganado Lake. J.L. Hubbell was a dynamic and interested man. Trader, politician, farmer, patron of the arts. Builder of a unique trading post and business empire. But after his death it all slowly faded away until by the early 1950s only the trading post in Ganado remained. Dorothy and Roman Hubbell lived there and ran the trading post. By 1957, Roman Hubbell, who used to cut such a dashing figure in his boots and riding britches, [10] was confined to a wheelchair. Without Roman to help her, Dorothy was beginning to find the trading post operation to be just a little more than she could comfortably handle. [11]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

hutr/adhi/adhi0c.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006